An Annual Music City Event

The International Black Film Festival

Perhaps one of the greatest hidden treasures of Music City, the annual International Black Film Festival (IBFF), is held on the last weekend of September (the same weekend as the Nashville Film Festival), and it just finished delivering another festival of amazing, cutting-edge cinema. Due to the presence of two festivals in one weekend, our indefatigable corps of journalists was spread quite thin. Of the IBFF, we were able to attend and review two Narrative Features (Four Walls, Million to One), a Marquis Documentary (Lead Belly: The Man Who Invented Rock & Roll), and one Collection of Shorts (Shorts Suite 4) which are always the most innovative collections. Along with the collection of two dozen long films and more short selections, the festival offered numerous industry panels on activism and the business, as well as after parties, and red carpets. As we said last year, next year we will cover more.

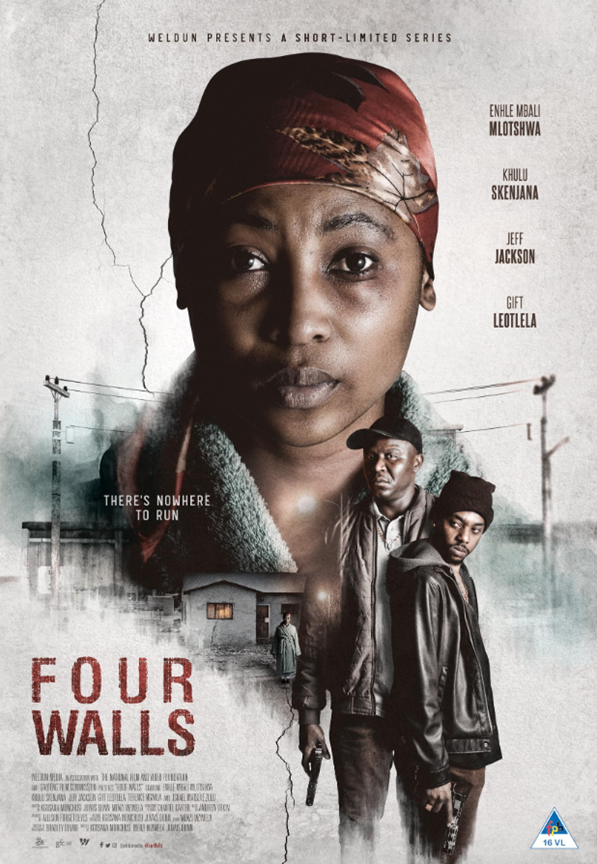

Four Walls, 2022 (Review by Angelica Trujillo)

What is the limit in the series of tactics that a woman must put into action for her survival? Why should she subject her essence to multiple incarnations of roles due to a rule of law that does not guarantee her protection? Four Walls, a South African film written and directed by Kgosana Monchusi, Menzi Mzimela, and Juvaiś Dunn, is the allegory of a consciousness that, imprisoned, does not sleep. It is the rumination contained between thoughts of anger, sadness, and nostalgia, but that simultaneously must execute a plan to jump to the next level of agony.

“Grace” (Enhle Mbali Mlotshwa), the main character of this drama, is a pendulum that swings in the middle of a masculine, violent, and criminal circle. This circle is made up of the man who in the past knew how to recognize diligence and charm in his wife, and who now wakes up bound and gagged in his bedroom. It is also made up of two criminals pursued by a police operation who seek refuge inside Grace’s home, and an “honest” and “gentlemanly” police officer who evades work to feed her adulterous desires. The plot unfolds in a tangle of suspense from the beginning to the end of the film. Grace’s house is the only visible setting for the development of events marked by anxiety.

It’s noon and the woman seems to repeat her daily routine; In the kitchen, she prepares a meal marinated with tears, and a glass of a fresh beverage is transformed into what will be the end of the misfortune. This period is interrupted by the thunderous and insistent knock on the door, Grace rushes to hide the evidence of her already-decided plan. Now she must protect her life from two outlaws who invade her enclosure and her chameleon-like attitude adjusts to the threat. The monument to the misery of a man who has not spared physical and psychological humiliation against his wife is an alarm for criminals who no longer trust the fragility of the hostess.

The preamble to the climax of the film is a series of unethical actions on the part of each character, but whose purposes have an almost altruistic background. With the empty glass on the table and a cartridge on the floor, Grace remains innocent among the bodies of the intruders. What better scenario than to notify the police that her husband has been murdered, and he serving as a witness to an unappealable sentence? Enhle Mbali Mlotshwa says that it was not a difficult role to play, gender violence is so latent in society that there are more than enough stories that she was inspired by, so, I could suspect that the permanent pain on her face may not be just part of the performance.

Million to One, 2023 (Review by Stephen Turner)

If any of us were to find a perfect partner in life, could we get past it and move on if we were to unfortunately lose them? Who do we have to turn to after such loss? These are some of the questions writer/director Harold Jackson tries to walk us through in this film. Jackson’s Million to One (2023) tells a story centering on the strong bond between brothers Dre (Rob Gordon) and Isaac (Michael Patterson) Shaw. Dre, an urbanite and rising social media influencer—DreShawFoodGang Bang Bang!—visits his suburbanite brother, Isaac, since, at the last minute, the latter and his fiancé Monica (Ashley Rios) decide to finally tie the knot. More concerned with reaching one million followers, Dre comedically bemoans his impromptu summoning by Isaac, taking every opportunity to blast suburban life—until there was the lovely Tatiana (Briana Cortesiano), the gourmet chef hired for the weekend.

Million to One is an exciting amalgam of a serious drama and a romantic comedy. Like a cross between Adam Szymkowicz’s play Kodachrome (2019)—about a man struggling to love again after his wife’s death—and the rom-com My Best Friend’s Wedding (1997)—where the groom’s best friend must get a bride to the alter before it’s too late—Isaac in Million to One, still grieving the loss of first wife, Stacy, goes missing leaving Monica to wonder on the morning of their wedding.

A strong point of this film is how it explores family and generational trauma. The film’s central characters are forced to confront long-term effects stemming from their issues of abandonment, loss, and emotional abuse. One of the two standout scenes is of a tender moment between actors Gordon and Cortesiano; in a more personal moment, audiences finally get to see a more mature and transparent Dre, and they can adore Tatiana for her warmth and inner radiance as well as her outer beauty. The second scene is a tear-jerking moment with Patterson portraying Isaac lamenting over his late wife while sullenly poised by her grave’s headstone. Dre is shone in a new and unexpected light, lifting his brother up, giving him warm encouragement and support, convincing Isaac that Monica is “the one.” In a sudden turn of comedic hijinks, Dre rushes Isaac back to the alter to be reunited with Monica.

Million to One’s soundscape—supervised by The Taco Pimp—comprises contemporary tracks from budding artists, including Leon Laudenbach, Scootie Wop, WXLF, and Ollie Joseph. A score standout is during the opening credits with the group Aves crooning “Try So Hard,” a cusp-1960s/70s-style funk/soul track that harkens back to the sound of The Isley Brothers. Additionally, several music tracks from Miami-based artist Duce Williams are included. Williams’s music is self-described as pulling “from multiple influences” with roots from the Bahamas and time spent in Sydney, Australia (www.ducewilliams.com). Listen for Williams’s instrumental version of “I’m Seeing Stars” during Dre’s night-driving scene.

Personal crisis is inevitable, and those who lift us up, to ride through such storms are essential in our lives. The big takeaway from this entertaining film is how it expresses the importance of maintaining familial bonds, and it stresses the necessity of dealing with our past traumas in order to make a fulfilling life possible in the present.

Lead Belly: The Man Who Invented Rock & Roll, 2023 (Review by Joseph E. Morgan)

A recent release from Tennessee’s largest film and video production company, Film House, Lead Belly: The Man Who Invented Rock & Roll is a strong and intimate depiction of Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter, a mainstay in the development of American Popular Music. The documentary is rich in stories given by famous folk, rock, and skiffle artists from the sixties and later, artists like Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, Paul McCartney and others. Like many stories of African American music of the 20th Century, especially those set in the South, Lead Belly is replete with myths, but thankfully, Director Curt Hahn is careful to only try to dispel those that he can, leaving unanswered those that he can’t. The difficulties are those that he doesn’t mention.

The movie opens with a depiction of Lead Belly’s childhood as privileged for his time and place, describing the luck of coming up in a small nuclear family (as a comparison, Robert Johnson was the 11th of 11 children). It soon shifts to his incarcerations, focusing mainly on the two knife fights, allegedly started by jealous men, and ended by Lead Belly with a knife. Hahn has his onscreen informants (there is no narrator) challenge and discuss the legend that Lead Belly sang his way to a pardon to end both of his longer prison terms. No conclusion is arrived at, but a nuanced look at the intentions and agendas of all involved emerges quite successfully—this is historical documentary cinema at its best.

Similarly, his relationship with the Lomax family is investigated and an uncomfortable narrative is spun depicting Lead Belly’s subservient attitude toward John Lomax as well as Lomax’s appropriation of Lead Belly’s music by claiming authorial credit. This narrative culminates with Lead Belly pulling a knife on John Lomax in order to get the money that he was owed, unfortunately neglecting to point out that Lead Belly would eventually, legally and successfully, sue Lomax for what he was owed.

In constructing his position as the “Man Who Invented Rock & Roll,” as the title implies, and as if the genre still commands relevance, the film points mainly to influence, with the most detail going to the songs that Lonnie Donegan appropriated and translated to skiffle; songs and a genre which would then influence the Beatles. There is a direct line there, but with Lead Belly’s larger presence in the culture and a catalog containing songs like “Midnight Special,” “Black Betty,” “C.C. Rider,” “Goodnight Irene,” and many others, it seems forced and unnecessary.

A deeper investigation into his unique playing style as the “King of the 12 String Guitar” and the way he got such an amazing timbre (like a tack-piano at times) from that huge 12-string guitar was largely unexplored. It seems that it is in this intention to establish Lead Belly as a hero, as the “Man Who Invented Rock & Roll” the film is prevented from fully exploring other, especially more challenging facets of his career. His avoidance of taking a political stance is mentioned, but without critical thought. Was he choosing to avoid politics out of safety, or was it a business decision? How are we to believe he was simply uninterested or strangely ambivalent?

Related to this are Lead Belly’s failed attempts to find success in New York by performing in Harlem’s Apollo Theater at the height of the Harlem Renaissance (January, 1936). He performed a skit devised to recreate an earlier newsreel. A skit like this would have done quite well on Lomax’s white college lecture circuit; however, Lead Belly’s appearance in prison stripes (to match the newsreel) was too much for the Harlem audience, or perhaps it was his subservient relationship with the Lomaxes? This is an important investigative opportunity that is simply missed. Almost 20 years later, and 5 years after Leadbelly’s death, Langston Hughes would write a stinging essay titled Slavery and Leadbelly Are Gone, but the Old Songs Go Singing On. In it he stated:

Well, I guess you know there was once a singer named Leadbelly, and he was a penitentiary boy, and he sang his way free. I guess you know he got locked up again, but he got out singing. And he sang songs from here to yonder. He sang himself great. He sang himself famous. […] He died while other folks made money from his records.”

Lead Belly’s actions, and Langston Hughes’ words are, of course, contextualized and explained by the impossibly difficult-to-navigate racial/political circumstances of their lives; circumstances that would lead one of the greatest literary voices of the period (Hughes) to attack one of the greatest musical voices of the very same period (Ledbetter). This, especially for modern audiences, needs greater exposition.

Towards the last decade of his life, Ledbetter began to experience success on radio and was being recognized internationally. Tragically, he succumbed to Lou Gehrig’s disease (ALS) in 1949. In the 21st Century, in the mainstream media, he is having a bit of a resurgence, cited as having the first recorded instance of the command “stay woke.” He used the phrase almost a century ago in relation to African Americans in the South who needed to be aware of their surroundings to avoid lynching. The use of the term has brought the apolitical Leadbelly into a modern political discussion that he most certainly would have avoided in his own lifetime.

I hate to be the reviewer who talks about his subject and how it should be instead of how it is, but I think this also represents the goals of the filmmakers– to restore Lead Belly’s relevance and place in American Music. Lead Belly was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame over thirty years ago as an “Early Influencer,” and that influence has been unmistakable. His covers from that faded genre include its kings, from Led Zeppelin to Nirvana, from The Beach Boys to The White Stripes. To restore Lead Belly as the “Inventor of Rock & Roll” is one thing, but I think a greater success would be to restore his incredibly interesting life as a model for the current mainstream style of popular music: Hip-Hop. Nurturing a bad reputation to sell records, carefully balancing between political positions to avoid recriminations from either side, staying woke to systemic forces that will chill an artist’s success are all actions and hard lessons that many modern artists could use as a model for their own lives. His life is still quite relevant in that way.

And yet, his old songs, as Hughes noted, still “…go singing on.” My daughter, just a few years ago learned his “Bring Me a Little Water, Silvy” with Nashville’s wonderful Met Singers. The organization was created to provide “…children the opportunity to develop leadership skills, to enhance their education, and to grow artistically and professionally.” It is wonderful to see a group of diverse, elementary-age kids master the somewhat complex clapping pattern and sing together, flush with pride, confidence, and joy in the sound they are making. Whatever the narrative position and title scholars and documentarians put on Huddie Ledbetter probably won’t matter as much in the long run as his music, and that’s the way it should be.

Shorts Suite 4 (Review by G. E. Tipton)

Shorts Suite 4, at the R. Milton and Denice Johnson Center at Belmont University showed five shorts. There was a well-planned variety in tone, length, budget, and production quality; I appreciated the openness of the festival to fun shorts, even when they only had access to small budgets. Often underrated, shorts are rarely seen in theaters (except perhaps before a Pixar movie), but I hope their success at festivals like the IBFF, the Nashville Film Festival, and everywhere online will change that.

The first short was Lettre La, where two West-Indian radio hosts respond to a letter in their advice segment, and you realize there’s more to the letter than meets the eye. It is funny and sincere with great production quality, well written and well acted. Unlike the other shorts, this has subtitles, which is probably unnecessary, but it was considerate of them to have them up for those who might struggle with understanding their accents.

Next was the Canadian entry Woman Meets Girl, a 17 minute LGBT drama, where a woman and her homeless houseguest share drinks, conversation, and possibly something more. The woman is in her forties and repressed, the girl is an 18 year old sex worker, and their opposing viewpoints on life and love are contrasted in their conversation. It was well shot, well acted, and the characters had good chemistry. Perhaps the relationship between the two women could be for the benefit of both, but it seemed that the adult woman had little wisdom to offer.

Just Food was the longest short, at 28 minutes, and is a humorous reflection by a man about his and his friends’ fear of commitment, settling for unhappy relationships that don’t challenge them. Some of the acting and production quality are uneven, but the writing is fun and funny, the message is solid, and the costuming is stylish.

That’s Our Time was the shortest of the lineup, at just under ten minutes. It is a cool, well executed idea: we sit in a mysterious man’s therapy session, where he talks about his dead-end job and his inability to bond with those around him. Its use of a digital timer beep as they talk about the shortness of life is effective, and the viewer’s sense of something sinister develops steadily. It left me wanting more.

One and Done, a local Nashville short, had members of the cast and crew present at the showing. A romantic comedy showcasing a terrible first date, the humor was goofy and slapstick, and my favorite bit was when the lead (played by Renard Hirsch) claimed that his car’s alternator was out of electrolytes. Michael McLendon, who wrote the screenplay, explained in the Q&A afterwards that he wrote this for school (he’s a recent graduate from Lipscomb) and that it is an amalgamation of several real-life experiences. The writing felt real, and Kimberly Jones’ portrayal of increasing hangriness was something everyone can relate to.

Having opened its doors in 2006, the IBFF’s mission is to “Encourage culturally accurate depictions of all people in film with special emphasis on providing a forum of access for underserved and unheard voices as well as to showcase the artistically rich creativity and diversity found around the globe.” To read more, and to join their mailing list (so you don’t miss next year’s festival) visit: https://www.ibffevents.com/aboutus