Between Two Worlds: The Musical Revolution of the Lafayette Tour

For Spanish, Click HERE

The Schermerhorn Symphony Center seems to have anticipated the Bicentennial Celebration of the Lafayette Tour by erecting its architecture in the neoclassical style and positioning itself only a few meters from the Cumberland River. On this occasion, the murmur of the hallways exchanged dialogues in French as guests made their way to the honorary reception. The Marquis de Lafayette once again arrived in Nashville, this time as an abstraction of memory and technology.

The Orchestre National Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes retraced the route of the Lafayette Tour to commemorate the Marquis’s second visit to a country that awaited him with open arms, in profound honor and gratitude. In the panorama of the American Revolution, Lafayette joined the fight for colonial independence, embraced the ideals of human rights, and advocated for the abolition of slavery, although his progressive vision met limitations within the practices of his time. What better choice to open this historical framework than the musical work of the Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745–1799), a composer of black descent from Guadeloupe who enjoyed the rare privilege of freedom and developed his artistic mastery in Paris. The program began with the overture to L’Amant Anonyme, the only one of his six operas that survives complete, possibly due to the unfortunate and intransigent Law of May 20, 1802, enacted by Napoleon Bonaparte to reinstate slavery and erase any record of Black participation in France.

The piece was introduced after a formidable animation projected at the back of the stage, which served as the guiding thread of the Revolutionary story and the musical repertoire throughout the evening. Recreating the political and aristocratic style of neoclassical painting, the French studio Holymage—renowned for its extraordinary visual experiences for major artistic events, including the mapping of Notre Dame Cathedral of Laon, the Château de Chantilly, and the Arc de Triomphe—transformed the concert hall’s screen into a vast canvas framed by the traditional golden borders of the period. Oil-painted characters were brought to life, interacting within the Marquis’s memorable adventures. The lifelike movement of garments, the undulating ocean, and the haughty galloping horses, coupled with seamless transitions between scenes, utterly captivated the audience’s senses. Each audiovisual segment concluded with program notes introducing the next work, allowing the musical narrative to emerge as an inherent element of the historical context.

The contrast between the gallant character of the overture and the subsequent piece, Andante for Strings by Ruth Crawford Seeger, invited an altruistic reflection that reaffirmed the commemorative aim. The narration mentioned the ‘Lafayette Escadrille’, a squadron of American volunteer pilots who fought for France during World War I, prior to their country’s official entry into the conflict. Evidently, it was fitting to include a composer from the “New World,” and it is reasonable to suppose, based on the program’s motivation to feature the Chevalier de Saint-Georges, that Seeger’s presence represents another “minority” voice within the political and artistic sphere of Western culture. The visionary spirit that characterized her compositional work, as well as her scholarly and pedagogical contributions, paved a valuable legacy within the American musical landscape, through both “ultramodern” innovations and the revitalization of folk traditions. In this transition from classical symmetry to the atonal paradigm, the Orchestre national Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes revealed itself to be a chameleonic ensemble, capable of capturing the genuine essence of each style. Personally, their performance captivated me; in earlier decades, the European approach to transatlantic musics often diminished their authenticity.

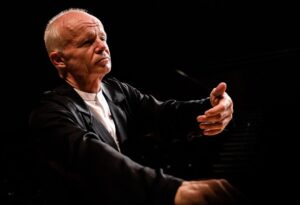

Immediately after, Austrian conductor Thomas Zehetmair stepped onto the stage wearing a different suit and holding a violin. With a few bow strokes, he introduced the Concerto No. 5 in A Major by a then-young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Performing a solo concerto often brings an anxious atmosphere among the musicians. Understandably so, given the orchestra’s responsibility to provide solid support in the accompaniment, the conductor’s intuition to yield before the soloist’s discourse, and the latter’s own exposure, requiring absolute technical and emotional command. On this occasion, the challenge was even greater, since it was the conductor himself who would take on the role of protagonist. Nevertheless, every movement unfolded in a reciprocal dialogue, allowing each phrase, each cadenza, to breathe with just the right freedom. The precise management of dynamics and articulations restored the natural charm of salon music.

Zehetmair’s performance was nothing less than a confirmation of his Mozartian heritage. Born in Salzburg, he laid the foundations of his musical career in the classical tradition, winning first prize at the International Mozart Competition at just seventeen years old. Since then, his extensive journey through the violin repertoire has established him as an international reference. The next piece, Passacaglia, Burlesque and Chorale for String Orchestra—a further surprise in this extraordinary event, being a world premiere—revealed yet another facet of the conductor. Drawn to the versatility of contemporary music, Zehetmair has also carved a path in the field of composition. From the mere eclecticism of the work’s title, one can sense the interrelation of traditional forms within a modern sound language. The harmonic and rhythmic progressions unfolded in broad textures and articulations characteristic of a period intent on exhausting every possible timbral resource.

At this point, the concert’s intergenerational conversation became evident, and it is no surprise that the evening closed with another great promoter of Revolutionary ideals. Though fitting within the contrasting program, Ludwig van Beethoven’s Great Fugue in B-flat Major also resonated eloquently within this pluralistic stylistic setting. Originally composed as the final movement of the String Quartet No. 13, it was fiercely criticized in its time as “eccentric” and “incomprehensible.” However, for later composers and analysts, it represents an avant-garde mastery of the Baroque form, capable of transforming musical material into a parable of multiple conclusions. The experience was complete, and the receptive audience was thoroughly immersed in each of the proposed allegories. Accustomed to every fine concert ending with an encore, Zehetmair returned to the stage to offer us an additional dose of Austrian spirito, performing the Fourth Movement of Mozart’s Symphony No. 29. With these melodies, the Marquis took his leave, resuming his journey aboard the steamboat toward the capital lands.