For Immediate Release from Chatterbird

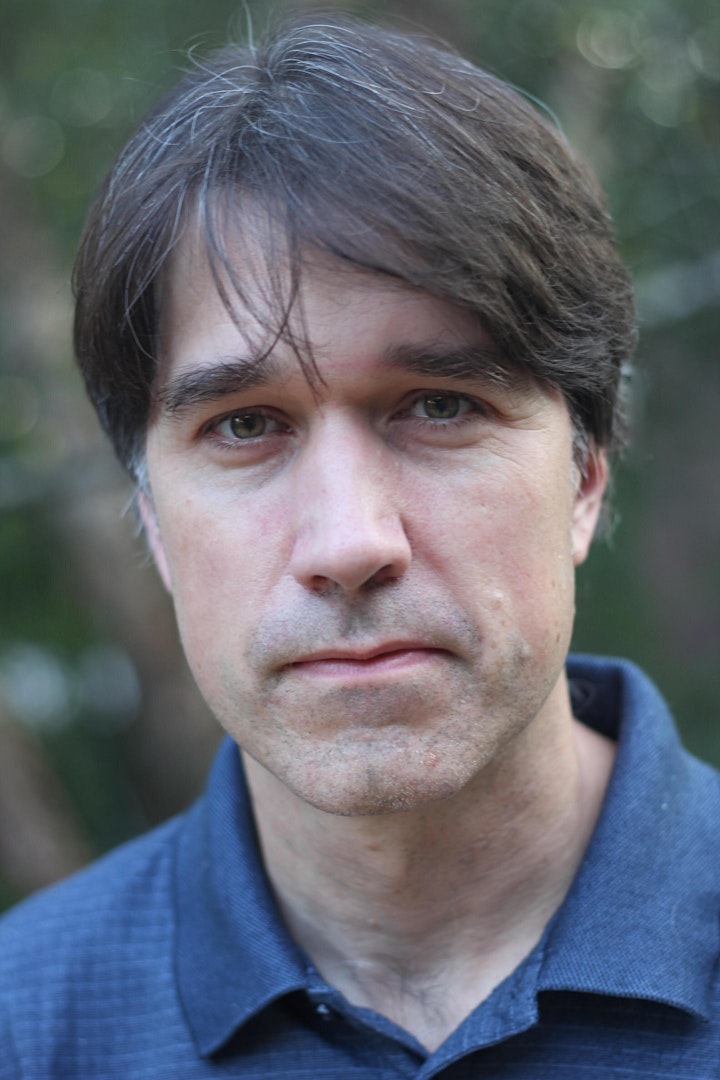

Mark Volker’s ‘Body and Soul, After the Plague’ to premiere July 29th.

Join chatterbird for the world premiere of Mark Volker’s Body and Soul, After the Plague, a free performance that will premiere virtually on July 29, 2021.

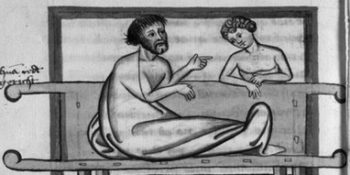

Based on the medieval text titled “The Body and Soul Debate,” the work will highlight the importance of empathy and diversity in humanity’s broader divisions, using the medieval conception of “sin” (self-division) as a transgression against both oneself and the fabric of the human community. It will premiere in Nashville at the Parthenon, and will be produced in collaboration with Dr. Suzanne Edwards, a medieval scholar, and Dr. Christine Rogers, a visual artist.

Two voices will be interwoven with music and film in a framing of a medieval poem, known as “The Body and Soul Debate.” This is a late fourteenth-century poem in which the body and soul of a recently-deceased person debate which is more responsible for leading them astray in life. Ultimately, it is clear that the debate only serves to teach them about one another, as they have a shared fate – and a shared responsibility in it.

To accompany this world premiere, chatterbird has created a beautifully-designed commemorative program booklet that includes striking images, background and commentary around the commissioned work, essays from artist/photographer Christine Rogers and medieval scholar Suzanne Edwards, biographies of the composer and performers, and more. Program booklets can be purchased for $25 via the eventbrite tickets link.

Following the premiere, chatterbird will host a virtual Q&A panel with the composer, Suzanne Edwards, and Christine Rogers, moderated by classical music journalist Colleen Phelps. Reserve your spot by visiting: https://forms.gle/mqjdzFuwpeoFf8MU9

Support for this concert has been provided in part by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Tennessee Arts Commission.

Jeremy Smith: “The Call”

Composer Jeremy Smith has just come out with his first foray into the operatic genre with The Call, a short drama that takes inspiration from Albert Camus’ novel The Fall. Although this piece can be performed in a traditional concert setting, Smith has created a performance specifically for YouTube that can be viewed here. Smith is a recent graduate of Middle Tennessee State University where he studied with Dr. Paul Osterfield and in the fall is headed to University of Alabama to begin his Doctoral studies in Theory and Composition.

One first note before digging into the work itself. During the previous 18 months of Covid-induced lockdowns it seems as if many performing arts organizations have discovered the internet for the first time. Performers and groups scrambled to convert their performances into a digital medium and frequently created videos that were uninspired, amateurish, and quite boring. In the Covid era of digital offerings, The Call is a shining example of things gone right. Smith, along with Continuous Motion Productions have created a video that is tailored to a video streaming service. More on the videography later.

The Call is a monologue centered around an unnamed protagonist, sung by tenor Charles M. Anderson. The protagonist makes an inebriated phone call to an old friend. Under the pretense of “catching up” the protagonist begins to reminisce about their past friendship which eventually devolves into a tirade against life and God. The music is flexible and unobtrusive which allows the text and vocal lines to lead the way.

The opening scene of the video shows the protagonist buying a six pack on a peaceful afternoon with bells tolling in the background. Smith’s music begins with big chords mimicking the tolling bells over a rhythmic bass propelling us into the busy thoughts of the protagonist. The scene changes to night; the protagonist has imbibed several Bud Lights. With enough liquid courage he calls his friend. This friend is shown on camera but is not ever shown speaking. The protagonist’s first line is: “Hey, are you still up? Nothing is wrong, I just wanted to chat.” Eventually his friend knows that something is up before the music cuts out completely just leaving the protagonist to lie: “Drunk? No, no no! I’ve only had a couple.”

Quickly trying to change the subject, the protagonist moves to small talk asking about his friend’s wife, kids, and new job. Smith sets this text to a hurried mixed meter. At this point, the thought that the protagonist has some self-destructive thoughts began to enter my head. The asymmetrical music highlighted the protagonists’ dissatisfaction with what he was hearing. Hearing of his friend’s success does not subdue his feelings so he steers the conversation towards the glory days of their friendship. “We would toast to the sunrise with the bottom of a bottle. We were ten foot tall and bullet proof” says he. “What happened? Maybe that’s just how life goes.” The jealousy really sets in as he adds a bitter “for some of us…” after that. Smith wisely allows the dissonance of the music to symbolize the growing dissonance between their two different lives.

From the beginning of this phone call the protagonist has been transparent on the real purpose of the phone call. After attempting to catch up and make some small talk the protagonist finally expresses his doubts that life has a plan and that “everything will work out.” He boldly declares: “As a matter of fact, I’ve got a theory. This is what I think: there is no plan. And if there is, it’s not a very good one.”

Growing tired of the protagonist’s ramblings, his friend puts the phone down and reads a book while the protagonist spills his guts. He mentions that maybe the protagonist should pray about it. Taking him up on his offer, the protagonist begins a half-hearted attempt at the Lord’s Prayer: “Oh God, who art in heaven, how could you lead me astray? Give me the strength dear lord to end it now.” The music is getting increasingly tense throughout this bungled prayer. At the climax of this moment the protagonist cries: “God damn you, God! Amen.”

One of my favorite musical moments happens on the words “Amen.” Throughout the religious diatribe Smith has not let any of the music stabilize. Extended harmonies are used throughout, meter changes happen almost every bar, and tonal centers are established and abandoned at ease. On the syllable “a” of the aforementioned “amen” the harmony comes to a rest on an A major chord before abruptly shifting to E major. This plagal (or ‘amen’) cadence is turned on its head. Usually, a cadence will solidify the tonal center of the music, but this one destabilizes the music further. The final line of the opera comes next: “Hello? Hello? Hey, are you still there?” Is the protagonist talking to his friend or God?

The Call’s main strength is its overall cohesion. The music, libretto, and cinematography combine to create something that is greater than the sum of its parts. For example, the libretto, written by Shane Wilson, is masterfully written to give us multiple pieces of information from a simple line. Take the opening piece of text: “Hey, are you still up? Nothing is wrong, I just wanted to chat.” Combined with the music this small line tells us multiple things. It is late and something is definitely bothering our protagonist. With each word being precious in an opera the strength of the libretto to help the story cannot be underestimated. Another example comes from the cinematography. Throughout the ten-minute piece there is a clear dichotomy between the world that the protagonist inhabits and the world that his friend inhabits. The protagonist is shown in a dark dingy apartment surrounded by emptied bottles and cans. His friend is reading a book by lamplight with an unopened bottle of wine by the window. Small details like this add an immense amount to the overall product.

Jeremy Smith’s score ties it all together nicely. The music is rhythmic and powerful throughout, switching between the various emotions being expressed. Each scene has an appropriate motif that accompanies the protagonist’s wide-ranging states of mind from nervous small talk, to outbursts against religion. Although strained at times, overall, Charles Anderson’s voice is strong and clear throughout. His expressive acting adds dimension and depth to the character. Richard Blumenthal, the pianist on the recording, does a superior job of navigating his way through the tricky score. This leaves me tremendously excited to see what Smith’s next operatic project will be.

From the Nashville Symphony

Chestnuts and Rarities in the Summer Chamber Music Series

As the Music City slowly reopens after the catastrophe of the last year, the musicians of the Nashville Symphony are beginning to return to the stage in the Lara Turner Concert Hall at the Schermerhorn. Billed as a “Summer Chamber Music Series” the concerts are, apart from being brief, socially distanced and mask required—they’re almost “normal.”

The first concert of the series, given on May 28 & 29th, featured a rather eclectic program. It opened with a selection of pieces by J.S. Bach arranged for Marimba and performed exquisitely by Symphony Percussionist Rich Graber. The was followed by a brief introduction from Concertmaster Jun Iwasaki, who seemed as happy as myself to have returned to the hall. He then performed Massenet’s wonderfully lugubrious “Méditation” from Thaïs accompanied by Licia Jaskunas on harp. This chestnut from the violin repertoire was the perfect choice to inaugurate the transition back to normal in the Music City. Written for the break between scenes of the second act of Thaïs, the meditation depicts the title character’s brief reflection before she decides to change her life. Iwasaki’s performance was spellbinding, especially leading through the central animated section. After the “Méditation” Jaskunas was joined by Robert Marler on piano to perform another meditative piece, Marcel Grandjany’s “Aria in Classic Style.” Jaskunas and Marler displayed a sensitive awareness of each other’s lines, which was especially clear in the later parts of the score as their timbres seems to merge in and out of each other’s sound, blurring distinctions.

The evening closed with the rarely heard Souvenir de Florence by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Composed in July of 1890 and revised in 1892, the piece is a sextet (two violins, two violas, and two cellos) in a standard four movement form, with the first two movements featuring themes that the composer had preserved from his visit to Florence and the later two movements featuring a more traditionally Russian sound and style. The first movement begins, seemingly in media res, with an abrupt theme that goes through a process of developing variation before it arrives at a cantabile secondary theme which Iwasaki and Jimin Lim gave in sweeping and beautiful phrasing. My favorite, the second movement brought the other instruments into the dialogue, first the cellos (Xiao-Fan Zhang and Keith Nicholas) and then the violas (Daniel Reinker and Anthony Parce). At one point in the movement Tchaikovsky has four of the six instruments playing entirely independent accompanimental lines as the first cello and second violin share the melody. The balance and synergy were so lush and downright symphonic that for a moment I imagined I was hearing our entire orchestra onstage.

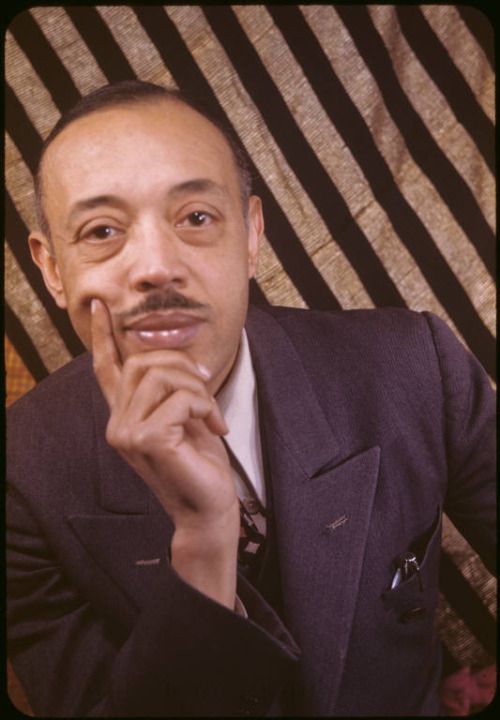

On June 4th the program was quite different, assembled of works for the standard quartet but included, in typical Nashville Symphony fashion, important works by American composers. The pieces were the second movement (“Andante Cantabile”) from Florence Price’s Second String Quartet in A Minor, the fourth movement (“Cumbia y Congo”) from William Grant Still’s Danzas de Panama, and in its entirety, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s K. 458 (“The Hunt”).

Best known for her songs and arrangements of spirituals, Price’s Andante carries the synergy of a folk blues sound merged with modernist compositional techniques in a counterpoint that is simultaneously vivid and nostalgic. Lim’s rocking ostinato provided a foundation for Annaliese Kowert’s melodic precision in a lovely interpretation. Still’s “Cumbia y Congo,” which was composed from collected themes from Afro-Latin dances, came across with an idealism and another take on the American sound. From the generous melody to the extended percussive techniques, the piece was magnificent.

Unfortunately, set against the exciting music of Price and Still, Mozart’s “Hunt” lost some of its magic. It was played very well, especially as the theme was passed around the four performers with the light delicacy demanded by its Viennese style. However, the problem was neither the performance nor the composition, but rather the program. To be exposed to single movements from these American rarities and then to hear the entire work of an old Viennese chestnut left me off balance. That said, it was so nice to be in a hall, listening to classical masterworks again!

There are two more performances in the series, which continues June 19th and June 25-26. All performances will run for approximately one hour without an intermission. Advance registration is required. Due to safety protocols, on-site registration is not available. Registration is free, and donations are very much appreciated. There are only 500 seats available for each performance, and they are distributed on a first come, first served basis. Seats can be reserved at www.NashvilleSymphony.org/SummerChamber

At Oz Arts Nashville

Sloppy Bonnie: Goofy Fun at OZ Arts.

The latest COVID-era production from OZ Arts Nashville, a company who has been kept amazingly busy during this hateful pandemic, is playwright Krista Knight’s Sloppy Bonnie. Billed as a “roadkill musical for the modern chick” and produced in association with the Vanderbilt Theater department, it tells a “morality tale” of a modern Southern belle who travels across Tennessee from Sulfur Springs (the Murfreesboro area) to visit her fiancé who is leading a spiritual revival retreat in the Tennessee mountains. Along

the way she is confronted by the challenges of “the American Southern Patriarchy.” The production’s concept is goofy fun, and while social distancing constraints forced the production to innovate, the staging in the building parking lot (as accessorized with a bar, a chicken truck, and a pink ’72 Nova with flashing, multicolored, dashboard lights) takes COVID’s bitter lemons and makes lemonade.

The cast is made up of only 3 actors who portray more than a dozen characters. Bonnie, the “Everyman” of this morality tale, is played by a charismatic Amanda Disney who is appropriately a little too loud, a little too gullible and twice as rambunctious as the situation demands. Her realistic portrayal of this charming and irreverent Southern belle can probably be attributed to two things—her youth in Birmingham, Alabama and her training at the American Musical and Dramatic Academy in New York City. Her delivery of punchlines was natural and fluent, and her intonation quite good (despite a few typical first night difficulties with the sound system). For playing her first professional role, she is downright amazing.

Both described as the “Male Chorus” in the program, Disney is flanked in the production by Curtis Reed and James Rudolph II. Rudolph is most hilarious in his depictions of both Jesus and Trucker Joe. His ability to bring a dry seriousness in the most ridiculous of situations provides an excellent foil to the loud, often screaming, characters portrayed by Reed—his most notable performances are as Bonnie’s competition in love and as the religious revivalist cum devil. These actors are amazing, their physical humor outstanding and each sang quite well in duet with Bonnie. From the narrative standpoint, I do think that, as a “male chorus” there is a missed opportunity here to give multiple (and contrasting) interpretations of Bonnie’s ‘animal-like’ actions onstage—perhaps this might have made the essential “moral,” and underlying feminist message clearer.

Director Leah Lowe’s blocking (like the choreography) is outstanding—a mix of tradition and function-defining form. Disney’s excursion into the audience as she seeks alcohol in a dry Tennessee county was a silly goof that will only get funnier as the production proceeds. Composer Barry Brinegar created a postmodern collage of southern popular music. From the cesura media res that references a car jump from the Dukes of Hazzard sans “the hateful symbolism of the confederacy” to the adaptation of Charlie Daniel’s anthem for the grand finale, the score matches the entire musical by being simultaneously high-minded and low brow with very little in the middle to explain the connections.

Indeed, the only problems for me resided in references to the musical as a morality tale or a feminist statement, and Bonnie’s final fowl transformation. At the end of the evening, I puzzled that Bonnie’s murderous acts had zero currency in the musical’s “morality.” Also, the whole script espoused a feminism neither consistently drawn nor clearly delineated. However, the next day I looked back at the program notes and noted Dramaturg Brook Fairfield’s description of Deleuze and Guattari’s “Becoming Animal” which explained these keys aspects of the production. No wonder I hadn’t “got” it, I hadn’t done the required reading! In any case, even though it went over my head, it was fun.

Sloppy Bonnie continues through June 5th at Oz Arts: you should see it and try not to think of Bonnie when you stop at the chicken truck.

At Oz Arts Nashville

Prism: A Performance Installation Experience

Running through next weekend at OZ Arts Nashville is David Flores’ new work, Prism, which is “…a performance installation experience created for a physically distanced world.” At times comforting and rejuvenating, and at others disorienting and troubling, the work is more descriptive of our current moment of coming out of a pandemic than prescriptive—it intimately expresses our “distanced,” and seemingly permanent state of dread and suspect hope. However, it offers very little in the way of escape or panacea. In four movements, the work spans 35 minutes and is presented in OZ Arts’ great Warehouse space in which the small and socially distanced audience is permitted to wander freely (within a designated area) all the while maintaining distance from the dancers and each other.

The first movement opened with New Dialect veterans Emma Morrison and Becca Hoback in the center of the room, circling a sculpture in string painted in red light from above. Falling in and out of tandem, the two dancers engaged their room with a remarkable charisma balanced by a cold, emotional distance. The music, composed by Vanderbilt Alum George Miller, similarly balanced a texture-based sound design created/performed by Adam Lochemes on laptop with the extended techniques of Alicia Enstrom on violin.

The second movement began, in a corner of the room, perhaps in quarantine, but certainly in a stylized domestic setting with the entire troupe of dancers (which, apart from Hoback and Morrison, include Lenin Fernandez, Rebeccah Peshlakai, Sarah Salim and Joi Ware). The choreography here was striking, as these dancers too fell in and out of synchronized movement, across and between the house structure. The choreography cross-cut the domestic setting and seemed to largely express the shared experiences both within and without the domestic setting. Accompanied by a reboot of Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young’s “Helplessly Hoping,” the nostalgia for an idealized family life was troubled and problematized by the dancers’ constant social distance.

The third movement’s sculpture was drawn of elastic string, which came to resemble any number of things, from prison bars to soundwaves, with the soundscape depicting a tension both emotional and material. The dancers pulled and pushed as the string gave way, but only enough to accommodate their movement in patient captivation—a kind of encompassing stasis that longed for progress.

The fourth movement, a reprise, brought Morrison and Hoback back to the center of the room and they entered the center of the sculpture where the floor is revealed to be water. It was overwhelming to see the intimacy of the two dancers when they enter the water, embracing, comforting, even baptizing, one another to an accompaniment that seemed inspired by Erik Satie’s Gymnopedies. This expression of both nostalgia and hope for intimacy accentuated the longing for physical and social contact that we all feel so deeply.

In all, Flores’ work is inspired; its abstraction is just thorough enough to allow one to read it into their own lives in any way that they’d like. Perhaps that is why he has titled it Prism? It will refract differently whatever light an audience might bring to it. As such, the experience will likely trigger the issues of separation that are already present in an audience’s mind and heart. In the current context, these feelings might be nearly universal, but isolation and loneliness certainly aren’t exclusive to this pandemic.

We’re Live….. Again!

Oz Arts of Nashville is back to live performances! Starting March 12th, Oz Arts will be performing PRISM to a live, socially distanced audience. PRISM was conceived and choreographed by David Flores. This live performance scored with music by

George Miller, also directed by George, features the following people: Lenin Fernandez, David Flores, Becca Hoback, Emma Morrison, Beccah Peshlakai, Sarah Salim, and Joi Ware.

According to their website, PRISM is, “A series of provocative movement episodes unfolds in

30-minute cycles featuring different combinations of dancers chosen at random. With choreography by Nashville-based artist David Flores and an original score by George Miller, PRISM invites audiences to examine personally held societal expectations and the ways we interact with one another at a time when relationships both private and public have been redefined.”

The audience is consistently standing and moving during this presentation however, you are able to acquire seating via request. The Oz Arts organization ensures the safety in this live performance by allowing small groups of audience members at a time. They traverse this wide, open area while seeing different interpretations of interactions that are heightened by, “ rich lighting and sound design to

explore aspects of voyeurism, our changing relationship to physical intimacy, and the role of chance in determining ultimate outcomes.”

Tickets for this live performance are $15. For more information about this performance, along with where to buy tickets visit their website here: https://www.ozartsnashville.org/prism/.

Cancellation of Rigoletto

The Nashville Opera was excited to return to the stage performing popular Opera Rigoletto by Verdi April 8th through the 10th . Unfortunately, due to the circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Opera has decided that it is in the best interest of everyone if they cancel the performance. The Opera states that ticket holders to this event may choose to either donate their ticket cost to the Nashville Opera, or receive a refund by filling out the form on their website (located here https://www.nashvilleopera.org/rigoletto).

The website continues on to explain that Subscribers’ status will not be affected by this cancellation. Once they are back to performing in-person performances again, the status of subscribers will be based on the 2019-2020 season. This cancellation does not affect any other performances that the Nashville Opera has planned at this time.

For more information regarding subscribers, tickets, or the Nashville Opera in general, please visit their website located here: https://www.nashvilleopera.org

Presenting Attitude

Attitude: A Two-Part Virtual Series Preview

Nashville Ballet is bringing back performances in early March this year. From March 5th through March 7th and April 2ndthrough April 4th they will be performing a virtual presentation of their new Attitude series. Attitude Part I will be virtually performed from March 5th through March 7th, and Attitude part II will be performed April 2nd through April 4th.

Attitude Part I will feature two popular works : Johnny Cash’s Under the Lights, and Jennifer Archibald’s Superstitions. Paige Atwell claims that Under the lights “gives viewers a unique glimpse into the life and legacy of the infamous ‘Man in Black’”. She goes onto explain the performance also has some collaborations with other famous Cash songs such as Folsom Prison Blues, I Walk the Line, and God’s Gonna cut you down. The music will be recorded Sugar + The Hi-Lows with a rockabilly twist. Along with the Cash performance, Part I will be joined with Superstitions with choreography by Jennifer Archibald. Paige claims that Archibald is, “Known for her unique style of movement that blends the precision and technicality of classical ballet with contemporary dance styles like hip-hop.” This portion will be accompanied with a score from local musician Cristina Spinei.

Attitude II is a much more classical ballet. It features Seasons, choreographed by Director Paul Vasterling, and is performed with Vivaldi’s Four Seasons recomposed by Max Richter. The Nashville Ballet hopes for this portion to be a, “fresh and uplifting view on the elements of classical ballet.”

The Nashville Ballet ensures that all safety measures are taking place to make sure that the creating of these performances are done so in the safest way possible. Tickets for Attitude Part I and Attitude Part II are available now and can be purchased here. To learn more about the Nashville Ballet visit their website nashvilleballet.com.