from the National Museum of African American Music:

A Review of Gospel: Panel & Watch Party

On Monday, February 12th, I had the pleasure of attending an engrossing and stimulating panel discussion at the National Museum of African American Music, sponsored, and curated by WPLN, Nashville’s local news and NPR station. This was a celebratory event of PBS’ new documentary series, Gospel: Where Song and Sermon Meet, written and produced by Henry Louis Gates Jr. The event took place in the Roots Theater of the museum. Among those included on the panel were Partick Dailey, countertenor, professor of voice at Tennessee State University, and the director of W. Cremm singers, and founder of the Nashville Gospel and Sacred Music Coalition; Tim Dillinger, gospel historian, journalist, and author of, “God’s Music is My Life;” Odessa Settles retired neonatal nurse, member of the family group, Settles Connection, and daughter of Walter J Settles of the Fairfield Four; and Dr. G. Preston Wilson Jr., the newly appointed director of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. The panel discussion was hosted by LaTonya Turner Riley with Nashville Public Radio.

The W. Crimm singers opened the event with a moving and energetic performance of ‘Oh Happy Day’ and ‘Even Me.’ Patrick Dailey’s soul-stirring countertenor voice rang out as he led the second song. I was overwhelmed by the beauty of his voice. The panel discussion began after the singers took their seats. Throughout the discussion, Tim Dillinger spoke truth to the essence of gospel music and the gospel sound, as well as its place in the current state of the global church. Odessa Settles provided a refreshing perspective on gospel music as a member of a musical legacy and how she uses her gift to spread gospel’s message of leading with love across multiple religions. Dr. G. Preston Wilson Jr. spoke on the significance of gospel music concerning inclusivity in the black church. Patrick Dailey discussed the diversity within the gospel music genre and the complexities of its sound.

This series strives to cover the continuously progressive genre that is gospel music. In the first episode, “The Gospel Train,” Gates briefly describes the spirituals and advances right into Thomas Dorsey’s historical contributions to the genre. He also mentions Mr. Dorsey’s involvement with singer and businesswoman, Sallie Martin. Gates provides appreciable insight into their journey together and separately. In this episode, there is also a conversation about the Baptist Church Convention and its position in the marketplace for recorded gospel music. There are references to the assorted styles of African American preachers and their contributions to the recording of Gospel and black spirituality. After spending a considerable amount of time discussing the professional relationship between Dorsey and Martin, the episode then shifts to the careers of Mahaila Jackson and Rosetta Tharpe.

Episode two, “The Golden Era of Gospel,” Gates mentions the rise of the male quartets in the 1940s. Its looser form of singing, the shout chorus, liberties in music, and the traveling of gospel artists began to rise in this stage of gospel music. The concept of taking ministry outside of the church became the main theme of this episode. Gospel’s ties to Jim Crow led Gates to talk about the career of Mahaila Jackson and how she globalized the gospel music genre. In connection to the sermon aspect, Gates talks about Reverend C.L. Franklin. He introduces the style of preaching that involves ‘hooping.’ This style of preaching was the first example of sermon and song meeting as the title of this series suggests. Artists, composers, and other vital figures mentioned in this episode were Sam Cooke, Mahalia Jackson, James Cleveland, The Clara Ward Singers, The Five Blind Boys of Alabama, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Alex Bradford. There is also a great amount of detail given to the relationship between Mahalia Jackson and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The bond between these two historical figures amid the Civil Rights Movement symbolizes the correlation between song and sermon regarding gospel music.

In episode three, “Take the Message Everywhere,” Gates discusses the impact of the Church of God in Christ, family dynasties within the denomination, and the major influence that they have had on the gospel music industry and ministry. This episode centers on how some notable artists took their ministry outside of the church’s four walls. With a significant emphasis on the contributions of the Hawkins family, Andrae Crouch, and The Clark Sisters; the concept of taking elements of secular music and incorporating them into gospel music became more prevalent during this new emerging era in gospel music. There was also dialogue concerning the rise of soul music. By highlighting the career of Aretha Franklin, Gates accentuates the influence that gospel music had on soul music and soul artists. In the aspect of sermon meeting song, and the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the attention to prophetic preaching became the next focal point in this episode. The ministry of Dr. Gardner C. Taylor led to the topic of the protest aspect of gospel music. This part of the series ends with a focus on the life and career of Shirley Ceasar. Her mastering of the ‘sermonette,’ which is a short form of preaching or shouting a sermon in song form; highlights the struggle women face in ministry in trying to gain equality with their male counterparts.

In the fourth and final episode, “Gospel’s Second Century,” Gates dives into the current state of gospel music. Beginning in the 90’s, gospel music takes a dramatic turn and completely steps away from the traditional sound. Gospel music starts to become a lucrative part of the entertainment industry. The commercial triumph of gospel music starts growing and reaching millions through radio, television, and box office success. Artists mentioned to draw attention to this shift in the genre include Yolanda Adams, Donnie McClurkin, and Kirk Franklin. The rise of megachurches was also a point of discussion. The career of T.D. Jakes and his “Woman Thou Art Loosed” brand propelled more non-denominational music and churches. There is a brief section about the style of preaching that was cultivated by the ‘Black Lives Matter’ platform, as well as the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The series ends with Gates’ final thoughts on the meaning of gospel music and its implications for black people and black culture in America.

Overall, my experience at this event was a great one. I thought that this series was an exceptional introduction to gospel music. However, more work must be done. Aside from Dorsey’s contributions, I felt that the spirituals from which gospel music derives deserve much more attention. There are so many artists and composers of this genre that are not mentioned enough. Composers such as Hall Johnson, Dr. Bobby Jones, Willie Mae Ford Smith, and Ella Sheppard. All of whom have been large contributors to the progression of gospel music. I was disappointed to see that Dr. Bobby Jones wasn’t mentioned when speaking on the televised or media aspect of gospel music. Being that Dr. Bobby Jones had the longest-running televised program on one of the biggest platforms for over thirty years. His show, “Bobby Jones Gospel,” was the only show of its kind to showcase local and international gospel artists from all facets of the genre. However, I feel as if Gates does captivate the essence of what gospel music was, is, and is becoming with this series.

From Belmont's Department of Theater and Dance

Blue Stockings

Tuesday evening, February 20th, I saw the Belmont Department of Theatre and Dance performance of Blue Stockings. It was a very enjoyable evening: the play is fantastic. It is about women at Girton College in Cambridge, UK, the first college to educate women, in 1896. As in the US, British women did not even have the right to vote at this time, and female higher education was contentious. The play begins with a male professor explaining to the audience that educating women is bad for their reproductive health: comic and insulting, like Aristotle’s famous, spurious claim that women have fewer teeth than men.

The term “bluestocking” originated as a reference to the Blue Stockings Society, an 18th century British women’s group that wore informal clothing (blue stockings) to their educational and literary discussions, which included notable men and women. It quickly came to be a derogatory term for an intellectual or literary woman. Blue Stockings is historical, showing the lives of students over the course of a school year as they go through the difficulties of being some of the first female college students in history. Their interactions with their male peers (who mainly refuse to acknowledge them as peers) are sometimes antagonistic, sometimes flirtatious or romantic. The head of Girton College, Mrs. Welsh, is fascinating: a practical idealist, she strives to get the university senate to vote on allowing her students the right to receive degrees upon graduation, but must struggle with balancing this goal with her other goals of education and suffrage.

Blue Stockings sounds like it could be dreary; like most people, I tend to avoid stories where the main characters are oppressed and unable to take action. But the play is quite cheerful and funny. None of the characters, male or female, are perfect people, and only one is entirely unlikable. Jessica Swale, the playwright, did a very good job of writing believable characters who think like people of their times– there are no shoehorned anachronistic characters or spontaneously generated postmodernists– and yet avoided forcing the false dichotomy, love-or-career choice upon their female characters. One choice is prominent in the play: what if you have to choose between fighting for women’s rights to receive degrees, or women’s suffrage?

The play is quality, without gimmick or self-conscious affectation. It is straightforward and authentic, and reminded me of the famous C. S. Lewis quote from the Weight of Glory: “No man who values originality will ever be original. But try to tell the truth as you see it, try to do any bit of work as well as it can be done for the work’s sake, and what men call originality will come unsought.” The play is full of the messages that many college students need to learn. As Dr. Jane Duncan’s director’s note quotes from the play : “The value of your lessons isn’t knowledge. It is the fact that you are learning to think.”

To see a teaser of playwright Jessica Swale’s feminist work, watch the comedy short Leading Lady Parts (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fpDHNbjGivo), about casting for a leading lady’s part. Full of A-list actresses, this short shows some painfully funny and accurate difficulties women still go through.

While Blue Stockings premiered in 2013 at Shakespeare’s Globe in London, it really works in the academic setting: to have a cast of college students and professors playing college students and professors, about a college and performing at a college, to a crowd of college students, professors, and college graduates– well, it’s very fitting. Modern students still need to learn many of the lessons explicitly taught in the play and the setting of students in class keeps these lessons concise and forceful. Somehow putting the morals in the mouths of professors in lecture avoids giving the play any feeling of pedantry.

The Belmont production is excellently cast. Victoria Herda plays Tess, the main character, and she balances the character well, keeping her optimism and naivety strong while keeping spirit and personality stronger. Kelby Horne as Mrs. Welsh is determined, strict, and driven, but avoids pedantry. Evan Fenne is kind and likable, even as he struggles to see the greater good past the immediate practical difficulties of women’s higher education. Shawn Knight is charming as Mr. Banks, a professor teaching at both men’s and women’s colleges, and displays that infectious love of learning that great professors pass on to their students.

The sets are very good: besides two groups of benches which remain on stage for most of the scenes and immediate props, many of the locations are designated by cutouts lowered from the ceiling with stylized renditions of books on shelves, trees, etc. What allows this rather minimal design to come together and feel vibrant rather than vacant is the lighting: the backdrop is awash in brilliant color for much of the play. Besides communicating moods and atmosphere through color, it gives dramatic energy to every profile, and makes the set changes much more interesting; instead of watching dim black-clad figures move around a darkened stage, we see black silhouetted figures moving swiftly; even the objects getting moved look viscerally satisfying.

Susie Konstans’s costumes make me really want an ankle length high-waisted skirt, and the women’s hair is fantastic. I don’t know the fashions of the 1890’s, but if it looks like that, I wouldn’t it mind it becoming the new retro-cool.

Blue Stockings is at Troutt Theater at Belmont, February 20-25. It’s a perfectly-sized theater with surprisingly comfortable seats, and it is very easy to find parking: within one block is is street parking, several parking lots and a Belmont garage. There are several tasty restaurants nearby, and why not get boba before the show?

For tickets and more information, see: https://belmont.evenue.net/events/BLUE.

Thoughts of a Colored Man: Town and Gown Triumph

The first morality play in Western culture was written in 12th-century Germany by a woman for women. Of its many characters, only one, the devil, was male. The most recent morality play was written in 21st-century New York by a man for men. As Mark Twain noted, “History never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme.”

For those who might have blocked out early college lit courses, a morality play pits good against evil, naming the characters for human emotions or character traits. Hildegard von Bingen, a convent abbess, wrote her allegory Ordo Virtutum [The Virtue’s Play] in the Bingen. Using music, narrative text, and poetry, it features one human soul torn between good, as represented by seventeen human virtues, and evil, the devil. Taking this unexpected, but still vital form, Keenan Scott II staged his allegory nearly 900 years later in Brooklyn. It features one human soul divided into seven characters. Using music, narrative text, and poetry, the characters address the unstaged demon of societal limits on black men.

Just as Hildegard’s art fought against the barriers of male dominance in Church hierarchy, Scott’s art broke barriers of white male dominance in modern American society, particularly Broadway, sometimes known as “The Great White Way.” Thoughts of a Colored Man is the first, the very first, play on Broadway written by a black man, directed by a black man, with a cast of all black men. In fact, in 2018 more than 93% of Broadway directors were white. Only 20% of shows were written by people of color. Although it ended its successful Broadway run only two years ago, the Roxy Regional Theatre was able to obtain the rights to produce the play in Clarksville, just north of Nashville. Kenneth L. Waters, Jr, the Roxy’s stage manager, and Scott, the playwright, are both alumni of Frostburg State in Maryland.

The performance was a triumph for town and gown collaboration as director Deonté Warren, Assistant Professor of Theater at Austin Peay State University, with Broadway credentials under his belt, worked wonders with APSU colleague Eboné Amos, who acted as costume designer, and a cast from varied points in the nation that included two Austin Peay alumni (playing Lust and Love).

The play traces one day in the life of seven varied black men: husbands, friends, coaches, working class, corporate class. Warren wisely chose a minimalist set of seven raised downstage doors, some painted with graffiti, with several pairs of steps leading to the stage floor where a bus stop and a drummer were on stage right, the drummer accompanying segments of slam poetry. The main set change was to the local barbershop, a sanctuary where all the men gathered.

Initially, the characters are not introduced by name, but when Jaylan Downes is constantly distracted by any woman happening by, when Branden Mangan constantly mourns lost dreams in his minimum wage job, and when Denzel McCausland, clearly the most prosperous of the crew, speaks in glowing terms of every aspect of his life, there is no doubt they portray Lust, Depression, and Happiness. Elliott Winston Robinson and Rosha Washington were also recognizable as Wisdom, an older sage, an immigrant from Nigeria and the barbershop owner, and Anger, a high school basketball coach whose glory days in professional ball were cut short by injury, but is more incensed by those taking advantage of the talented young men in his charge. It was a bit more difficult to distinguish between Corey Finley’s character as an idealistic poet, best friends with Lust, and Shawn Whitsell as Wisdom’s son-in-law expecting the elderly man’s first grandchild. Passion and Love are often too close to call.

Unlike medieval morality plays, Thoughts was a delicately nuanced portrayal of a black man’s complexities using poignant metaphors with fluid skill. Depression, for example, was an MIT student but could not pursue his dream of becoming an electrical engineer because his AIDs-ridden mother cannot raise his younger siblings alone. He gives his entire paltry earnings as a grocery store employee to his family, all the while thinking that “the aisles are fields and the cereal boxes and condiments are cotton.”  In the barbershop, one character who is hiding something finds himself surprised as the conversation moves from a humorously effective scene of their shared interest in a basketball game on TV closer to the more dangerous territory of his secret.

In the barbershop, one character who is hiding something finds himself surprised as the conversation moves from a humorously effective scene of their shared interest in a basketball game on TV closer to the more dangerous territory of his secret.

But the names can be deceptive; perhaps that is why they are not fully revealed until the last scene. The complex characters flow from anger to pathos, from fear to joy, from distance to empathy, just as in real people in real life. The audience, who often engaged in call and response with meaningful lines, is reminded that for black men in American society, “the color of our skin makes us men before we’re ready.” This prepares us for a tragic event.

Through the elegance and passion of his writing, well-interpreted by the actors, Scott implores us to see black men as people, complex people. Hildegard saw her works as “reflections of the living life,” the ultimate truth. When describing the play rehearsals for its New York premiere, Scott said “it’s been healing, it’s been therapy, sometimes it feels like church.” To that, we, the receptive audience, could only say, “Amen.” Ultimate truth.

This play is worth the drive from Nashville. The remaining performances will be held at 7 pm on February 22, 23, 24 and 2 pm February 24. There is free parking nearby and since the theater is in downtown Clarksville, food and drink at a French café, a steakhouse, and a pub/brewery are all less than a block away. Tickets are $35 (adults) and $15 (10 and under) and there’s a “dinner and show” package.

For more information: https://roxyregionaltheatre.org/thoughts-of-a-colored-man/

Coming to Darkhorse Theater: The African Company Presents Richard III

This play, written by Carlyle Brown, is about an actual historic event: In 1821, forty years before Lincoln ended slavery, and fifty years before black Americans earned the right to vote, the first black theatrical group in the country, the African Company of New York, was putting on plays in a downtown Manhattan theater to which both black and white audiences flocked. Yet the drama reached further than their stage: while putting on a production of Shakespeare’s Richard III, a rival white company at the Park Theatre put on their own production of the same play right next door.

As Director Dr. Lawrenace James says in his interview (The African Company Presents Richard III: Interview with Director Lawrence James – The Music City Review), “…[the play] really focuses in on their lives as actors, as African Americans in 1821 America, and the dissonance and the happy times too: the positives of being free African Americans, but having to try to put on a show and to compete, of course, with a much more established white company and some of the famous actors that they’re bringing in from Europe and whatnot. So it is history, but it’s also character study…there are a few scenes and monologues from Shakespeare’s play, but the story is really the company’s story: who they see themselves as, and where they came from, and what they do with their jobs and their relationship with the majority-white world, how they play that. And then, coming to try to be an artist and perform a great piece of art, but how is the character in Richard III different from the character in real life?”

Performances are February 22-24, 7pm, at the Darkhorse Theater. For tickets and more information, see The African Company Presents Richard III Staged Reading — The Nashville Shakespeare Festival.

from Cheekwood's Winter Concert Series:

Salsa Night in Cheekwood Gardens with the Music City Latin Orchestra

(Versión en español aquí: https://wp.me/pabEmc-2Ky)

As part of Cheekwood’s Winter Concert Series, on Saturday, February 24th at 7:00 pm, the authentic flavors of salsa will be savored in the Massey Auditorium. The Music City Latin Orchestra, under the direction of Giovanni Rodríguez, compiles, in their repertoire, the acclaimed hits of artists such as Benny Moré and the legendary Buena Vista Social Club orchestra. Just as 1930s New York began to exude tropical aromas amid its jazz and blues offerings, Latin rhythms found their way into Nashville’s bars in the late 2010s. In this favorable scenario, the Music City Latin Orchestra consolidates itself as one of the most representative ensembles of salsa in the city. Its characteristic name was not chosen in vain; this orchestra is made up of Latin American artists residing in the metropolitan area, acting as ambassadors of Caribbean music.

The Music City Latin Orchestra represents the iconic salsa orchestras that emerged during the first half of the 20th century. Before the Revolution, Cuba permeated the United States music scene with its elaborate salsa instrumentation that resembled those of the Big Bands. Latin percussion, syncopated melodies, and energizing improvisations progressively gained followers in the North American country; jazz artists were attracted to incorporating these sounds into their compositions, giving rise to genres such as Latin Jazz.

Afro-Cuban rhythms like son, mambo, guaracha, rumba, and guaguancó were the foundation of what is now known as salsa. However, due to its success throughout the continent, it has adapted and merged with other genres and styles. The Music City Latin Orchestra aims to preserve the genuineness of pre-revolutionary salsa, even organizing concerts that pay tribute to the most representative artists of that era. This is undoubtedly one of the main attractions of their musical proposal; in their performances, the audience is exposed to the colorful harmonic weave of the winds and the unmistakable beat of the timbales.

Anyone who has listened to salsa has inevitably succumbed to the hints to follow the rhythm with their body. The insistent call of the clave makes even the shyest stand up. And although the combination of steps is not simple, salsa adjusts to the joy of each of its listeners. In this rhythm, solos find dance partners, and couples alternate to add variety to their improvised choreographies. Regardless of the venue, the Music City Latin Orchestra offers a celebration experience. So, put on your most comfortable shoes and get ready for an unforgettable evening full of Latin flavored sounds. To purchase tickets and get more information, you can visit the following link: Cheekwood Winter Concert Series.

de la serie de conciertos de invierno de Cheekwood:

Noche de salsa en los jardines de Cheekwood con la Music City Latin Orchestra

(English Version here: https://wp.me/pabEmc-2Kz)

Como parte de la Serie de Conciertos de Invierno de Cheekwood, el próximo sábado 24 de febrero a las 7:00 pm, en el Auditorio Massey se degustarán los auténticos sabores de la salsa. Music City Latin Orchestra bajo la dirección Giovanni Rodríguez, recopilan en su repertorio los aclamados éxitos de artistas como Benny Moré y la legendaria orquesta Buena Vista Social Club. Así como la Nueva York de 1930 comenzó a desprender aromas tropicales entre su oferta de jazz y de blues, en los bares de la ciudad de Nashville los ritmos latinos fueron abriéndose espacio a finales de la década del 2010. En este favorable panorama, Music City Latin Orchestra se consolida como una de las propuestas más representativas de la salsa en la ciudad. No es en vano su característico nombre, esta orquesta la conforman artistas latinoamericanos que residen en el área metropolitana actuando como embajadores de la música caribeña.

The Music City Latin Orchestra es la representación de las icónicas orquestas de salsa que surgieron durante la primera mitad del siglo XX. Antes de la Revolución, Cuba impregnó la escena musical de Estados Unidos con sus elaborados formatos de salsa que se asemejaban al de las Big Bands. La percusión latina, las melodías sincopadas y las energizantes improvisaciones fueron progresivamente ganando adeptos en el país norteamericano; artistas de jazz se sintieron atraídos de incluir estas sonoridades en su composición dando inicio a géneros como el Latin Jazz.

Ritmos afro-cubanos como el son, el mambo, la guaracha, la rumba y el guaguancó, fueron la base de lo que hoy se conoce como la salsa. Sin embargo, debido a su éxito a lo largo del continente, se ha adaptado y fusionado con otros géneros y estilos. Music City Latin Orchestra procura preservar la genuinidad de la salsa pre-revolucionaria, organizando incluso conciertos que rinden tributo a los artistas más representativos de esta época. Este es sin duda uno de los grandes atractivos en su propuesta musical; en sus interpretaciones la audiencia está expuesta a la colorida trama armónica de los vientos y el repique inconfundible de los timbales.

Quien haya escuchado salsa inevitablemente habrá cedido a las insinuaciones de seguir el ritmo con el cuerpo. El insistente llamado de la clave hace poner de pie hasta al más tímido. Y aunque la combinación de pasos no es sencilla, la salsa se ajusta al regocijo de cada uno de sus oyentes. En este ritmo los solos encuentran pareja, y las parejas se alternan para dar variedad a sus improvisadas coreografías. Independientemente del recinto, Music City Latin Orchestra ofrece una experiencia de celebración. Así que busca tus zapatos más cómodos y prepárate para una inolvidable velada con toda la sazón latina. Para adquirir las entradas y obtener más información puedes ingresar al siguiente enlace Cheekwood Winter Concert Series.

The MCR Interview:

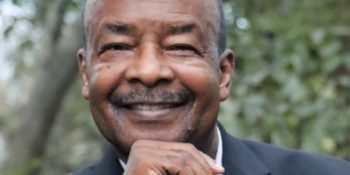

The African Company Presents Richard III: Interview with Director Lawrence James

Dr Lawrence James is directing a staged reading of The African Company Presents Richard III with the Nashville Shakespeare Festival at the Darkhorse Theatre February 22-24. This is a slightly edited transcription of his phone conversation with Grace Krenz on February 15, 2024.

Grace Krenz: When I first saw on the Nashville Shakespeare Festival website, The African Company Presents Richard III, I got very confused despite its clear title, because I was like, “is this the Nashville Shakespeare Festival or is it the African Company, which is in Nashville, presenting Richard III? Then I googled it and was like, “oh, it’s a play by Carlyle Brown and it sounds absolutely fascinating.” So, could you talk us through a little bit of the history?

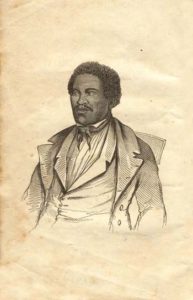

LJ: Yeah, it is a fascinating story and I’m just so glad that Carlyle Brown tried to bring it to life in some way. The history of the play itself is that it concerns a true incident in New York City in 1821, where a troupe of free African American actors mounted a production of Shakespeare’s Richard III, and the play did attain critical and financial success. But then a larger white company, the well-established Park Theatre, during that time, connives to shut the production of the African Company down, to prevent competition with its own production of Richard III at the same time. And so the play focuses in on the company of African American actors. They go through their typical rehearsals and look at the reviews, and war about their roles, and how successful they are, and their costumes and all the other things that all actors go through. And at the same time they fill in a lot of their own background details, of their own special circumstances. For example, most of them work and they have other jobs, particularly the ladies, who work as domestics and so they talk about their servitude and a couple of the major characters are from the West Indies. And so the play does go back in time through memory in some moments there, and back to the present. You have some element of attempts at romance, but it really focuses in on their lives as actors, as African Americans, in 1821 America, and the dissonance and the happy times too: the positives of being free African Americans, but having to try to put on a show and to compete, of course, with a much more established white company and some of the famous actors that they’re bringing in from Europe and whatnot. So it is history, but it’s also character study, personalities of Blacks during this time.

GK: Wow, that sounds fascinating. Was the African Company a newer theater when they started to put on Richard III? Had they been established for a while?

LJ: Yes they had, the company had been founded by William Brown. He was a free African American coming from the West Indies. The company would put on plays regularly and they had a very good following of Blacks in New York during that time. In fact, Brown used his own home and the plays would be done in his backyard, particularly on Sunday evenings, and so you have a lot of the Blacks coming in as a Sunday outing. People would be in their Sunday finery, and so in addition to maybe going out to get some ice cream or something like that they would go and gather in Brown’s backyard and see these plays. So yes, they had done a number of shows.

GK: And so when they were presenting Richard III and being successful at that, were they still doing it in his yard, had they rented a theater or some other location?

LJ: Well, this is where it gets to be interesting. Yes, they would rent a theater, and they were going bigger now. They were being more expensive. So they’d started in the backyard, and then they went and they would begin to rent space. And here in the play, where the conflict gets real, they rent a ballroom in a hotel right next to the Park Theatre, where the other Richard III was being presented. And so you have quite a conflict here with the managers, Brown being the manager of the African Grove Company, and Richard Sheraton being the manager of the Park Theatre, and the police get involved, so it has some interesting twists and an ending to it.

GK: It’s kind of meta in a Shakespearean way of having the play within the play. I find it funny if the villain is gonna be the leader of the white theater, his name is Richard and the villain of Richard III is Richard. That’s just very tidy, I like that.

LJ: [Laughs] Yes, that’s right.

GK: Now was this the first Shakespeare play that the African Company did, or was this one of many?

LJ: This was one of the first Shakespeare plays that they had done. They had done some other original things there, and then near the end of the play we find out that Brown becomes motivated to write some more plays. So no, this was not their first play, but it was one of their first Shakespearean productions that they did.

GK: So these two competing theaters are trying to, instead of doing a dance-off, do an act-off. Was there a big disparity between the manner of their presentation, or the sort of costumes or attitudes going into it?

LJ: Well, in regards to the black actors, that’s a part of the story. One of the themes, or the subplots here, and I’ll kinda jump forward and say, [Carlyle] Brown introduces his play with the poem “We Wear the Mask” by Paul Laurence Dunbar. And in that poem the persona says, “We wear the mask that grins and lies, It hides our cheeks…” Then it goes on, “And why should the world be overwise? We grin and we smile but oh what all we have to bear,” and then it ends with “we wear the mask.” So the play is not that specifically about performing Richard III, even though there are some monologues and some scenes. It’s more about the characters and their joy, for some, in performing, but the dissonance and the conflict that others have in, you know, I have to say “yes sir” and “yes ma’am” and bow and do my servitude and clean the house and cook and do all of these things, and then I come and I play Lady Anne or I play a King Richard, or this other person who I’m not able to “be” or show to the real world. And so that’s really the story. Once again, there are a few scenes and monologues from Shakespeare’s play, but the story is really the company’s story: who they see themselves as, and where they came from, and what they do with their jobs and their relationship with the majority-white world, how they play that. And then, coming to try to be an artist and perform a great piece of art, but how is the character in Richard III different from the character in real life? And that is really the story.

GK: Dang, that is really interesting. I feel like this play seems to be covering one of those gaps in our education or historical understanding. I feel like at least, growing up, I never heard about the plight of African Americans living in New York City forty years prior to the Civil War. So I don’t have a good understanding of what their legal status would be like in the city. “Free,” but unable to vote. But how does that come across if you’re a tenant, or you’re trying to rent a ballroom? Did they come across some of the difficulties of what later would be segregation in the South, or were they more free at that time?

LJ: You know, that’s a great question. From the play itself we don’t get a lot about the kinds of experiences they may have as far as going about everyday life. Some of the characters do relay about some of the white people that they work for, and what that experience is like. And so there’s some positives, but they also talk about the negatives of that. It does relate some of the problems of being out in groups and maybe some of the harassment that comes about by the police if you’ve got too many Blacks during this time gathering. And oh, especially, of course, when you have the Blacks that do protest the Park Theatre, and that’s a serious conflict that comes about. But other than that, as far as being able to rent the ballroom next door to the Park Theatre, as one of the characters says, “As long as we’ve got some green,” some money, they will rent it to you. So only in the instances where there’s a gathering and particularly, when the Blacks are protesting, do we get a feel of the law of the police coming down on them. But other than that, we are told about their everyday life working, about the Sundays when they’re free and they’re able to dress up and go promenading out to the park and whatnot. So there’s kind of a balance between the negatives of being Black in New York during this time. And of course they were “free” Blacks, but of course there were some problems that were experienced there. But no, I think the play kind of balances it out with the positives and some of the negatives.

GK: So I looked up this play and saw it was first published in 1994. How did you first come across it?

LJ: I was familiar with the play and with the story. You know, it’s such a great and intriguing title, as you say, we look at The African Company Presents Richard III, so I was familiar with the script, but it really came into focus by way of Denice Hicks and the Nashville Shakespeare Festival. Denice has served on our theater advisory board for a number of years, and that was one of the ideas that she had brought some time ago, several years ago. She was interested in talking about it, “you know, this is such a great script, I’d love for us to think about doing it.” So it came about this past year, well maybe two years ago, that we really sat down and we talked about it. In fact, there was supposed to be an actual staged performance of this play, this month, at this time, here on the campus of TSU, as a collaboration between our theater program and university, and Nashville Shakespeare Festival. However, it fell through at the last minute, and was primarily by way of TSU. Nashville Shakespeare did an awesome job of stepping forward, really wanting to do something for the community, for the university, for the students, as well as for them, because they do do those kinds of things with other universities as well. So that was actually scheduled during this time slot here, but as I said, that fell through, and so Nashville Shakes decided to at least go with a staged reading of the play, off-campus, without any ties to TSU.

GK: Would you describe the difference between doing a staged reading and a full-fledged performance?

LJ: Sure. Well, you know, staged productions rely on a very inextricable relationship or balance of dialogue, conversation, character, interplay, paired with physical action, character business, to tell the story. The staged reading has very limited movement and there’s a variety of styles of staged reading, where you have the cast sit with the folders or the script and just read, other variations maybe you have the cast reading with reading stands or reading and up and doing actions. So there’s a lot of different variations with that, but the focus is more on the reading and creating the action through the dialogue of the characters with limited physical movement. Whereas of course, in the staged production, action and business of the characters tell the story in conjunction with the dialogue and the words of the script.

GK: For your performance, not to ask you to give spoilers or anything, but what sort of style of staged reading will you go with?

LJ: We’ll see what we’ll do with the script and with reading stands and whatnot. We’re exploring the space and the stage so I’m finalizing some thoughts. I’m thinking that we’re probably going to be using scripts with movement. It will still be a reading: acting and performance with some movement to tell the story, but we won’t be just sitting, reading, the entire script. No, there will be some movement, blocking, action, along with the actors using the script as they play the characters.

GK: As an artistic director, how is directing a staged reading compared to directing a fully staged performance?

LJ: Of course they are similar in ultimately being able to tell the story, bring the script to life, actualizing it in performance: well what did Shakespeare intend in Richard III, what does Brown intend in the African Company Presents? A major difference is getting the audience to visualize in the staged reading. That is, getting the audience to see the action of the play primarily through hearing, with some movement as opposed to seeing live action. So there’s more emphasis, I think, on the language, on the imagery, and the actors being able to color those images vocally. So that implies a lot of vocal agility, vocal expression, facial expression, without taking the play completely out of the mind of the audience. So it’s that balance of language, the creation of language, imagery, action, without losing the story, because the actors do have the script in hand, and so, you know, how literal are you? How much movement there? So it’s a balancing act. Vocal, life, with some suggestions of movement, to get the audience to see the action in their minds. And some of it visually too, to a limited degree.

GK: Well excellent. Now I think that I went through all the questions I had, but do you have any question that you think I should have asked and that you have a good answer for?

LJ: [Laughs] No not really, I’ve enjoyed talking with you. I’m appreciative of you doing this, we’re looking forward to it. But yes, I think that there’s a lot to be learned in this show; it’s history, it is life, it is the past but it also is the present as well. And I think that those who come and see will be glad that they did. And who knows, in the future maybe we’ll get an opportunity to actually do a staged production of the play. That would be wonderful.

GK: That would be fantastic. I’m looking forward to seeing the show! Thank you for speaking with me and taking time out of your day!

LJ: Thank you!