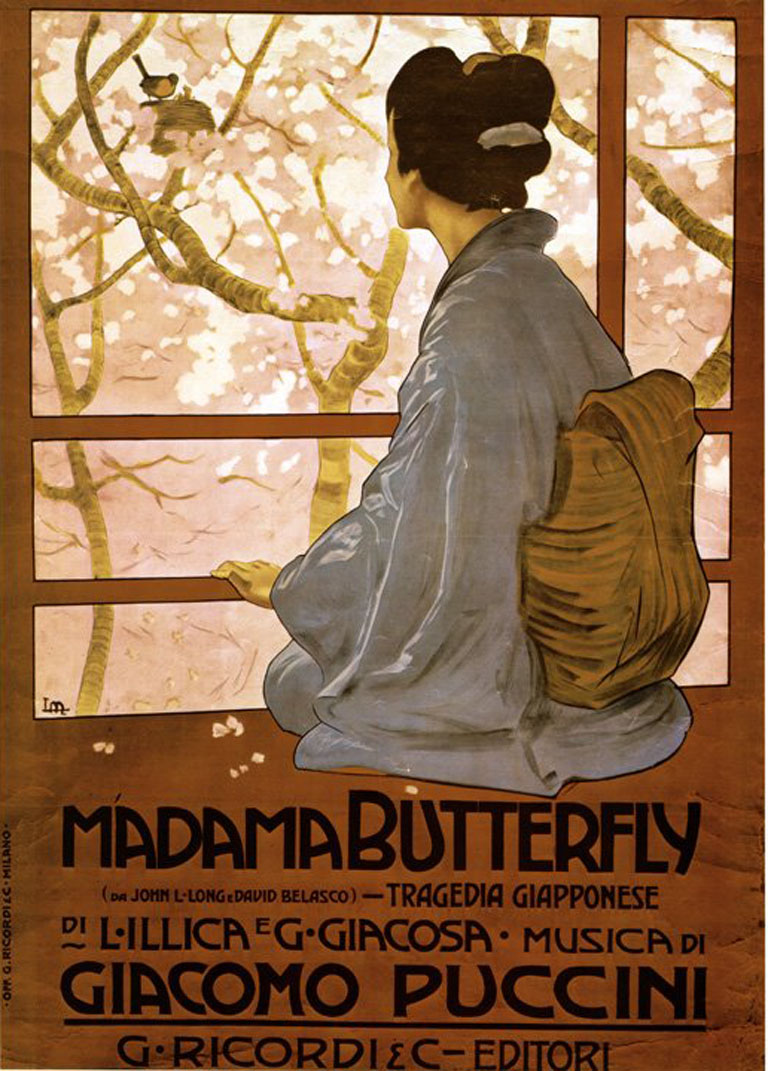

Nashville Opera’s Madama Butterfly

On October 10, Nashville Opera opened its 2019 season with a delightful production of Giacomo Puccini’s Madama Butterfly at the Andrew Jackson Hall in the Tennessee Performing Arts Center. The production, starring the Cuban American lyric soprano Elizabeth Caballero, was remarkable for the exquisite vocal performances as well as its heart-rending telling of Puccini’s tragic tale.

Completed in 1904, Madama Butterfly, like most of Puccini’s works, rests uncomfortably somewhere between the long evolution of Italian opera and an expression of the verismo movement of the time. First a movement in literature and then in opera, a verismo narrative is characterized by a naturalistic setting in which a poor or common character is driven to a catastrophic end by, as W.H. Auden once put it, “…an impersonal natural need outside his control.” These impersonal, natural needs are typically social constructs of religious and/or societal norms.

In Madama Butterfly, the expectations of marriage and family are the societal norms that drive Puccini’s exotic heroine, Cio-Cio San (aka Butterfly) to marry Lieutenant Pinkerton, and to wait for him when all others have given up hope for his return. It is Pinkerton’s undermining of these expectations that ultimately lead to her suicide. However, Cio-Cio San is not a common woman. Born wealthy, she is not forced to make immoral decisions due to these impersonal needs; rather, she is able to make markedly moral decisions despite those needs. A woman with an undying faith is a stereotype in Romantic opera, one thinks of Agathe (Der Freishcütz), Senta (Der Fliegende Holländer) or Desdemonda (Otello) and in this way she is almost a typical opera heroine set within a tragic verismo context.

Caballero, with her grace, charismatic presence, stamina and wondrous instrument, is cast perfectly as Butterfly. Indeed, she thrives in Puccini’s relentless setting. From her entrance aria early in the first act, where she is brought to the very top of the soprano range, until the very end, Caballero’s intensity and presence was remarkable. Her central aria, “Un bel dì vedremo,” was simply astonishing, her delicate voice’s gentle timbre clearly articulating Butterfly’s hopeless optimism.

Maestro Dean Williamson and the Nashville Opera Orchestra deserve mention here for their subtle handling of Puccini’s motivically organized opera. Apart from the “Un bel dì” motive, which is overtly reprised at Pinkerton’s return, Puccini’s motivic designs are less directly referential than his earlier works, with some creating more of a musical atmosphere and ambiance. Williamson handled this subtle design with great care, all the while maintaining the incredibly important balance in Puccini’s Orchestra—the heavy orchestral brass accompanying the “heroic” Pinkerton versus the lighter and more delicate presence of Butterfly.

For his part, Adam Diegel played a dashing Pinkerton, with a bright and polished tenor that made his naïve seduction of Butterfly quite believable. His and Cabllero’s voices blended with a surprisingly poignant intimacy at the end of the first act in their duet “Viene la sera.” Pam Lisenby’s costuming was simple but elegant–Pinkerton appears in the first act in a heroic white uniform but returns in a dreaded black uniform. The straight and square lines of his uniform contrasted powerfully with the flowing curves and colorful prints of Butterfly’s kimonos.

Sharpless, the American Consul, is one of the most innovative of Puccini’s narrative characters. This baritone part, a voice type traditionally reserved for the antagonist, here plays the role of a Greek chorus, warning Pinkerton (and the audience) of the approaching catastrophe and commenting on it afterwards. As Sharpless, on Thursday Lester Lynch seemed to have some difficulties in terms of power in the first act, but by the second his voice bloomed into a well-rounded sound that carried throughout TPAC’s very difficult hall. His acting was delightful, at times humorous and at others reprimanding.

If Sharpton communicated the wrongs in Pinkerton’s seduction, Suziki, played by the wonderful Cassandra Zoe Velasco, expressed the pain that it inflicted on Butterfly. At the end of the second act, her flower duet with Butterfly was delightful when their voices gently blended in a magical moment as cherry blossoms floated down from above.

Joel Sorensen, as the marriage broker Goro, was pretty darn funny, as was Brent Hetherington as Prince Yamadori (Hetherington doubled well as “The Bonze”). The blocking of the production was genius with Kate Pinkerton (Sara Krigger) innocently invading Butterfly’s space and privacy; an encroachment on Butterfly’s world that served as an immediate and symbolic expression of Western imperialism’s influence on the East.

In all Director John Hoomes has pulled off another success and it bodes quite well for a fun season of Nashville Opera, which will return in December with a production of Gian Carlo Menotti’s holiday opera Amahl and the Night Visitors.

Gateway Chamber Orchestra Presents

Ultra-Romanticism at the Franklin Theater

Deceptively spacious and nestled between two storefronts on the aesthetic and quaint Main Street of historic Franklin Tennessee, the Franklin Theater welcomes a vast array of events from musical theater performances to the traditional film screening. Warm, regal golds and reds decorate the interior, accentuating the intimacy of the venue to accommodate the crowd that anxiously awaits the Gateway Chamber Orchestra. People chatter excitedly in anticipation, and this specific audience is full of groups of people who are already familiar with one another, making the room feel even more responsive and pleasant.

The program for the evening of September 30th boasts an ultra-romantic offering of Gabriel Fauré, Carl Reinecke, and Franz Schubert, with the headline of “Artistry of Lorna McGhee,” highlighting the featured soloist (a series given by the organization that draws from masterful musicians across the country). With musicians hailing from the Austin Peay State University faculty to the Nashville Symphony, the orchestra itself carries so much influence and notoriety that even discounting McGhee, the audience is promised a high-caliber musical experience. President and conductor Gregory Wolynec takes the podium in preparation for the performance, but before the orchestra begins, he seizes the opportunity to introduce the pieces on the first half of the concert so that the audience has a framework for which to follow the program.

Gabriel Fauré’s Pelléas et Mélisande, a suite of incidental music based on the play by Maurice Maeterlinck of the same name, follows the titular characters through their turbulent love to their untimely demise. The central theme of the play revolves around the cyclic nature of creation and destruction for the sake of love- the beautiful Mélisande marries the galant Goloud in response to his acts of chivalry but soon after falls in love with his younger brother, Pelléas, which ultimately leads the pair to their deaths. Though Fauré hesitated to sacrifice his musical content and integrity for the sake of conforming to an external narrative (he was an absolutist in the argument that pervaded the 19th century about the purpose of music), his score sets the atmosphere for the play, even slightly utilizing the leitmotif technique, without depicting every change of character and mood.

Opening with a lilting melody beautifully executed by the violins, the first movement occurs at a spring where Mélisande has lost her crown in the water. She despairs, having left a life of turmoil and wanting no remnant of her former existence. This peaceful setting grows through an ever-ascending melody, warm sounds emitting from the strings and woodwinds, before two disruptive hunting calls in the horn, marking the arrival of Goloud. Resonant and strident, the horn calls between the rich chorales in the strings is a lovely dichotomy. La Fileuse, the title of the second movement literally translating to The Spinner, functions as an orchestral rendering of a spinning song. While the first violins spin away their expertly even sixteenth-note triplets, an interplay of double reed declarations forms the initial melody. Principal oboe Roger Wiesmeyer adeptly establishes a precedent of flowing lyricism and lush tone for all who follow to emulate. Undoubtedly the most renowned movement from this suite, though the last movement to be added, the Sicilienne not only uses prior unpublished material of Fauré’s, but has also since been adapted into works for solo cello and piano (variations include solo transcriptions for other instruments as well). Lisa Wolynec shines on flute, her sound delicate and lovely. An omission from this performance is La Chanson de Mélisande, which provides some motivic material utilized in the fourth movement, the depiction of Mélisande’s and Pelléas’ deaths. Juxtaposed over expansive phrases in the strings are marked dotted rhythms in the woodwinds that enforce the idea of a dirge. Having played much more of a background role to this point, the trumpets have a stark moment of color, Rob Waugh and Alec Blazek striking the perfect balance within the ensemble. The ending of the piece is muted and quick, portraying the fall of the hero and heroine with little fanfare and much lament.

When Lorna McGhee takes the stage, the audience falls into a trance. The sound that emanates from such a small vessel is breathtaking. McGhee fills the entire theater, commanding both the audience and the orchestra. She is literally moved by the music, and all her movement is tied directly to the musical content as she interacts with the orchestra. Her technique serves as an extension of her voice and body, working hand in hand with her musicality, and she allows every level of her dynamic playing a

character and color to which she naturally associates. A staple in the flautist repertoire, Carl Reinecke’s three movement concerto exhibits much gorgeous melodic material over diverse styles and opulent harmonies. The primary theme of the first movement is a soaring gesture that winds its way through the full ensemble as the soloist remarks on these statements with conversational virtuosity. McGhee interacts flawlessly within these pairings. One of note is a duet where the violin outlines the melodic structure while solo flute fills out that skeleton with arpeggiation- Concertmaster Emily Hanna Crane and McGhee perform this so tastefully. In contrast to the sweeping Romantic ideas in the first movement, the initial theme of the second is more akin to a funeral march. This movement alternates between this metric lamentation and a more hopeful and rubato response until a final return to the first statement and a final note so clear and shimmering that one could feel the audience hold their breath. Fluid cascades of notes and virtuosic passages fill the third movement, which McGhee breezes through with ease to the concluding triumphant cadence.

Schubert’s fourth symphony closes the program. The subtitle “Tragic” was attached to the piece by Schubert himself sometime after his completion of the work (he finished this composition at the ripe age of 19 years old). Though the opening statement occurs in a minor key, the majority of the following themes and developmental sections center in major. Why he would choose the word tragic to define this work that is seemingly the opposite is unknown to this day, though some scholars speculate that he may have been trying to garner publicity for the premiere. Schubert takes influence from Beethoven for the construction of this symphony, utilizing specific thematic material in the first movement (as well as the development of this material between the first two movements) and certain compositional devices that can be found in Beethoven’s string quartets. Heavily featured in this symphony is the woodwind section with beautiful exposed contributions from bassoonist Dawn Hartley and oboist Wiesmeyer. The third movement is a boisterous romp with shifting metrical impulses and huge dynamic changes that prepares the momentum into the yearning first theme of the fourth movement. A true finale, the Allegro boasts an impressive number of notes that are carried skillfully by the entirety of the orchestra, providing an apt denouement for a concert that relies so massively on individual artistry and musicianship. Full of rich sonority and lyrical phrasing, this performance of the Gateway Chamber Orchestra uses Romance and distinct virtuosity to bestow a beautiful production upon its audience that fully showcases the brilliant Lorna McGhee.

At OZ Arts Presents

Instant Standing Ovation: “Electric…Profound…Beautiful”

Experiencing contemporary art can sometimes feel like stepping foot into the unknown: one must be patient

and open your mind to the possibilities of what humans can create. Avant-garde Japanese artist Hiroaki Umeda brought to OZ Arts an unabashed contemporary presentation that feels like a fluid, sensorial experience mixed with fierce commotion that breaks the boundaries between body, light, and sound. Patience and open-mindedness are a virtue here. This is artistic director Mark Murphy’s first international guest to visit OZ Arts, and Umeda is truly an artist that encapsulates today’s contemporary art field.

Umeda began the evening with ‘split flow’. He is small, compact, and very still. A slow build, the dance begins with movements of various speeds. These eventually grow to something greater, while he is also expressing his velocity with light. How Umeda can fill the space and create an experience that pulls the viewer away from reality is striking. And the piece, ultimately, is exploring two distinct physical conditions – one that is dynamic and one that is static. With the intervention of body into static space, a different reality can be created with every stroke that the artist makes, every variation of light that paints the artist, and every sound that infiltrates the space.

Eventually, the listener can discern that the sounds are of different mass – whether it be water, oil, or air. And

that is just how sound can influence the space it enters, the body can also influence the space around it. The bursting yet tranquil light will make itself known and stop a scene in its tracks. Meanwhile, the glaring sounds will fight back and alter reality once more. And the dance of it all is just that: several mediums encountering, coexisting and influencing each other into totality. It’s satisfying knowing there’s no plan or motive to be had – but instead, various realities that pull the viewer in because of this entrancing dance.

These same workings are explored in the harmonious second piece, ‘Holistic Strata’, where “the common denominator of all movement is expressed in the distortion of hundreds of pixels.” The work is daring even by

contemporary standards. It’s as if Umeda has this entire dance coursing through his veins, and the utter cool factor of it all is what Nashville’s contemporary scene truly craves. Engulfed in swarms of pixels, the dancer’s

physicality is ultimately influenced by the varied world that the pixels create throughout the space. But the viewer perceives that the dancer’s body can just as easily manipulate the universe around him even as it is influencing the dancer.

This back-and-forth between chaos and synchrony can be interpreted in numerous ways. Ultimately, Umeda is creating a living organism that challenges the senses, and the result is chilling. Yes, the viewer can easily sit idly by and not give the pandemonium much thought, but what’s the fun in that? Just as Umeda creates and alters this mysterious world he created, he also challenges us: to experience sensations preceding the materialization of emotions. This is the oddness of it all, as well as the beauty.

Sustainability and environmental awareness were central themes when Intersection partnered with the Portara Ensemble this past Saturday evening at Lipscomb’s new Shinn Event Center for a concert billed as “Renewal”. It is only fitting that a concert addressing awareness of 21st century problems do so through the vehicle of 21st century music – and the program reflected this with a slate of works all written within roughly the last decade.

Sustainability and environmental awareness were central themes when Intersection partnered with the Portara Ensemble this past Saturday evening at Lipscomb’s new Shinn Event Center for a concert billed as “Renewal”. It is only fitting that a concert addressing awareness of 21st century problems do so through the vehicle of 21st century music – and the program reflected this with a slate of works all written within roughly the last decade.

The opera takes place in Nagasaki, Japan and opens on the day of fifteen-year-old Butterfly (Cio-Cio-san)’s wedding to American Lieutenant B. F. Pinkerton. Unbeknownst to Butterfly, Pinkerton’s intentions of their marriage are not of love, but status. Sharpless, the American consul, advises him to consider the consequences of breaking Cio-Cio San’s heart. Instead, Pinkerton boasts that he can cancel his marriage at any time and he looks forward to the day when he can marry a “real” American bride. The geishas arrive with Cio-Cio-San and the wedding proceeds with her family, friends, and servant Suzuki in attendance. The celebration is cut short when Butterfly’s uncle arrives and announces to everyone that Butterfly has secretly converted to Christianity for her new husband. The wedding party is horrified at this accusation, and denounces Butterfly, leaving her crying with Pinkerton alone to console her.

The opera takes place in Nagasaki, Japan and opens on the day of fifteen-year-old Butterfly (Cio-Cio-san)’s wedding to American Lieutenant B. F. Pinkerton. Unbeknownst to Butterfly, Pinkerton’s intentions of their marriage are not of love, but status. Sharpless, the American consul, advises him to consider the consequences of breaking Cio-Cio San’s heart. Instead, Pinkerton boasts that he can cancel his marriage at any time and he looks forward to the day when he can marry a “real” American bride. The geishas arrive with Cio-Cio-San and the wedding proceeds with her family, friends, and servant Suzuki in attendance. The celebration is cut short when Butterfly’s uncle arrives and announces to everyone that Butterfly has secretly converted to Christianity for her new husband. The wedding party is horrified at this accusation, and denounces Butterfly, leaving her crying with Pinkerton alone to console her.