At the Schermerhorn...

Shostakovich at the Nashville Symphony: This is Why Art Matters.

As I write this, and most likely as you read it, we are both secure in the tacit knowledge that despite the imperfection, inequality, and division present in our current political climate, we aren’t in any real danger of being executed by our country’s leaders for our opinions on social issues, government, or art. For us, the Orwellian concept of “thoughtcrime” remains a cautionary tale from a literary work rather than a tangible threat to individual freedoms.

This seems like a fairly simple concept – especially in the ridiculously connected 21st century when even the most mundane facets of life (like the pronunciation of GIF) devolve into vigorous online debate. As we approach the third decade of the new millennium, perhaps we’ve become a little complacent in our capacity for dissent and our right to communicate it. But, as the Nashville Symphony’s programming this past weekend illustrates, freedom of expression isn’t a universal guarantee, and it isn’t always free. Sometimes the costs can be severe.

The Nashville Symphony’s presentation of Shostakovich’s Fourth Symphony this past Saturday began by inviting the audience to first understand the context (both historical and personal) surrounding the creation of the work via Beyond the Score® – a series originally developed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra to provide audiences a deeper understanding and connection to composers and their works through a multimedia presentation featuring, video, musical excerpts, a narrator, and an actor.

The narration detailing the political climate surrounding the Russian Revolution and Stalin’s eventual rise was regularly underscored by musical examples, video footage, and portrayals of Stalin, Shostakovich, and his colleagues. The audience was invited to consider not only the political circumstances of the early twentieth century, but also the impact these conditions had on those whose work and art were used in defense and promotion of the ideals favored by the powerful.

Tying the narration, video, and commentary back to the piece itself was very effective. It was particularly helpful to hear musical excerpts that could be interpreted as either bolstering party ideals, or defying them. These kinds of references to external influences are not really a stretch. After all, Shostakovich used a factory whistle in his second symphony – a fact referenced in the presentation. But, in addition to the modern musical technique found in the fourth, these references begin to become much less overt and depending upon interpretation, these kinds of allusions may be dangerous. Much of Shostakovich’s output exists in this land of double meaning. For example, his String Quartet No. 8 of 1960 is publicly dedicated to the victims of the Dresden firebombing, but the grief expressed in the work is often attributed to Shostakovich’s own feelings at having been forced to join the Communist Party. With few exceptions, his orchestral works are also subject to multiple interpretations. Scholars sometimes debate his true intentions, but his musical prowess is rarely questioned.

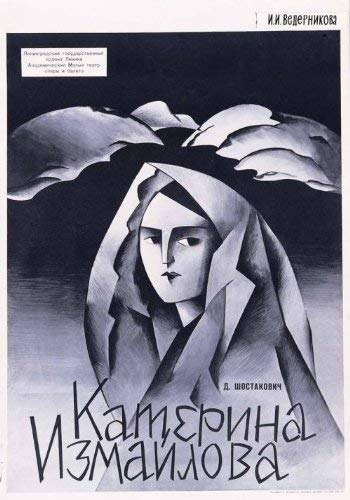

Shostakovich’s Fourth Symphony was written during 1935-36, but did not receive its premiere performance until 1961. Before he was denounced in an unsigned Pravda article in January of 1936, he had been held up as a kind of wunderkind and a Russian musical hero. Shostakovich had garnered international fame for his early symphonic output, but despite its success in Russia and abroad his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District displeased Stalin. The attack in Pravda accused Shostakovich of failing to represent the aims and truth of socialism and instead appealing only to the backward ideas of the bourgeois. During this time of social upheaval men had been jailed and even killed for much less.

After its completion, Symphony No. 4 was scheduled for performance in December of 1936. Its contemporary technique and musical language was sure to draw the same kind of condemnation leveled at Lady Macbeth, but the composer was determined to advance the work. Though the circumstances surrounding the decision are not completely clear, the piece was pulled from the concert with a press release stating that this had been done at the composer’s request. Shostakovich would have to wait 25 years to finally hear the work.

The opening of the fourth is nothing short of a wake up call. Piercing woodwinds and percussion supported by violent string tremolos immediately transition into an insistent pulse featuring brass fanfare gestures. From the outset the ensemble’s energy and attention to detail were evident. Though the fourth calls for the largest orchestra of any of Shostakovich’s symphonies, the meticulous and challenging writing is transparent in even the largest tutti sections – and the technique of the symphony was on full display. The dazzling and devilish quasi fugato string passage that occurs near the end of the development was a highlight of the movement. Maestro Guerrero’s bright tempo allowed the string section a chance to show off, and the clarity of the gesture as it descended through the section was impressive. Despite the fireworks and extreme dynamic shifts displayed in the opening and revisited at the recapitulation, Shostakovich ends the movement with what might be described as an anti-climax shepherded by a slowly expanding rhythmic statement in the English horn as the emotional intensity of the long first movement dissipates, but is not forgotten.

The second movement begins with an initial thematic gesture that, along with a repetitive rhythmic statement, serves as the genesis for the majority of the thematic material. The theme begins in the strings and is eventually developed into an intervallic canon spaced across four registers of woodwinds before it explodes into a full woodwind tutti counterbalanced by soaring horns playing the secondary theme. While they aren’t directly connected thematically, the descending canonic treatment of this theme leading to the climactic statement of the horns recalls (at least for me) the blinding string fugato in the first movement.

The pace of the movement was well crafted by the ensemble, and the expansion of the woodwind canon (piccolo, flute, clarinet, bass clarinet) into what can only be described as a relentlessly driving woodwind reed organ, was masterful. The orchestration in this section is simply ingenious – creating a sense of cathartic arrival for the horn section’s emphatic theme. The climax quickly fades into another subdued ending featuring a “ticking” statement in the percussion and a soft but agitated reprisal of the original theme in the strings punctuated by a flutter tongue in the flute and piccolo and a single xylophone note.

Shostakovich’s final movement begins as a funeral march, but quickly defies any and all convention by featuring light-hearted waltzes, dance inspired passages, and even heroic statements – all in abrupt transitions of almost slapstick quality at times. Shostakovich’s bleak humor is on display in the movement, and the orchestra was agile enough to navigate these changes without sacrificing the individual character of any of these sections. According to the noted musicologist Robert Greenberg, satire and irony were “at the heart of Shostakovich’s secret expressive language” and this sense of irony is how “generations of Soviets maintained their sanity”. This ironic and sometimes satirical treatment is essential to Shostakovich’s music, and when required the orchestra presented the appropriate moments with the satirical whimsy or gravitas needed.

The conclusion of Symphony No. 4, like the ending of the first two movements, is somewhat subdued when compared to the bombast present in each of the individual movements. The impossibly soft sustain in the string section, and the repetitive arpeggiated gesture in the celeste, culminating in the final intervallic expansion of the celeste statement was nothing short of magical. Given the technical demands of the work and the soloistic nature of the writing, offering adequate praise to the efforts of individual musicians within the orchestra would require a much longer review than this one. But for me, the best moment of the evening was the slow musical exhale that constituted the end of the work. The audience was spellbound and sat in perfect silence for a full twenty seconds before acknowledging the ensemble.

To some, such a subdued ending may not square with the fear and rage that Shostakovich must have felt working under a repressive regime that threatened his life as well as his art. But in reference to the similar ending (also featuring celeste) of Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 13, Yevgeny Yevtushenko (the poet whose work “Babi Yar” inspired the 13th Symphony) commented, “…there is power in softness, there is strength in fragility.”

This is significant as Shostakovich’s dissent was perhaps most transparent in his Symphony No. 13, written during the “thaw”, but his true expression has been apparent to careful listeners since some of his earliest works. Without the repression, censorship, and fear he experienced surrounding Symphony No. 4, the triumph of his later works, specifically the clear defiance of his Symphony No. 13, might not have been as poignant. To borrow from Yevtushenko’s comments – the power present in vulnerability comes from our ability for empathy and is enhanced by the communicative nature of music. Symphony No. 4 is a true masterwork, and the Nashville Symphony’s commitment to music that is emotionally and artistically adventurous is inspiring.

It gives voice to the voiceless and can stand defiant in the face of seemingly unconquerable authority.

This is why art matters. It gives voice to the voiceless and can stand defiant in the face of seemingly unconquerable authority. The art that we produce and consume is a commentary on our humanity and all of its triumphs and sorrows. This was as true for Shostakovich as it is today for artists all over the world whose work is censored, banned, or punished. The fear and artistic constraints that haunted Shostakovich should not be dismissed as a relic of the Cold War era. This species of censorship and intimidation in the arts is still alive – and it must be confronted. Organizations like the Nashville Symphony are aiding in this effort by continuing to raise awareness through the programming of works that tackle important issues directly, and just as importantly by providing education and outreach allowing audiences to fully appreciate this art in context.

And for this, I say BRAVO to the Nashville Symphony – not only for a wonderful performance of an excellent and often neglected piece of music, but also for shining a light on the importance of art and its vital contribution to a well informed and free thinking public.