At the OZ Arts Website:

Burdens from a Distance

Carrying burdens: a universally accepted part of life and timely theme as the world shares a collective burden. Over the course of three years, speaking to hundreds of people from all walks of life, Jana Harper discovered the same underlying concerns we all share: “our loved ones, our futures, our planet, and of course, our health.” This Holding was created from the exploration of these burdens, portraying this portion of the human experience in a raw, beautiful, and thought-provoking way. During a period when many feel more alone than ever in their lives, Harper holds a fitting sentiment about her work: “If This Holding could leave you with one feeling, I hope it is the knowledge that you are not alone.”

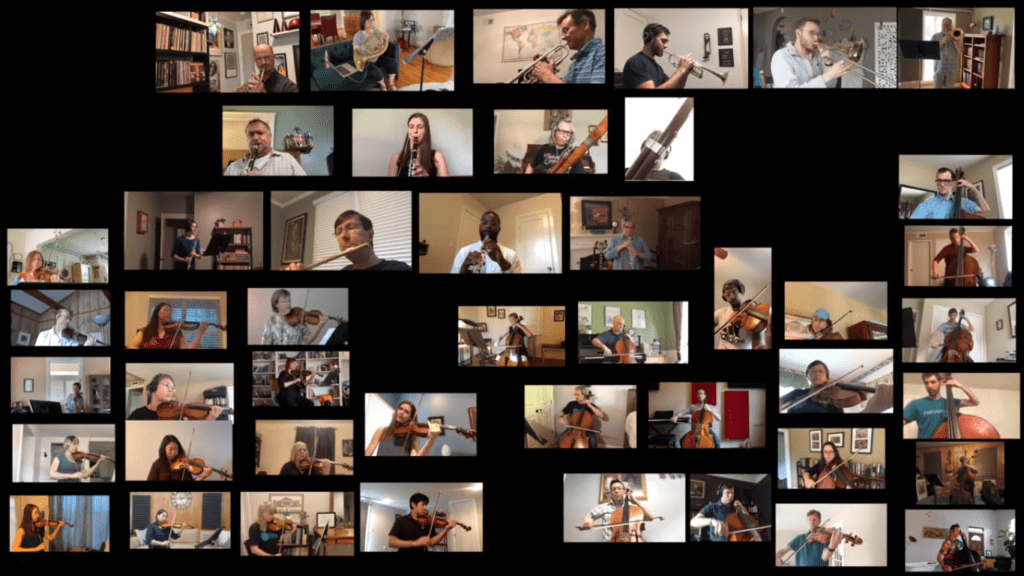

This Holding: Traces of Contact, rather than being performed live, was presented as an online film event by OZ Arts Nashville in response to the widespread healthy and safety concerns due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Originally conceived for the stage, once rehearsals were stymied by prohibited in-person gatherings and the assembly of a large audience was out of the question, the entire creative team quickly pivoted in order to re-imagine the work for film. In a live Q & A session following the performance, members of the team commented about the transition of the creative process and how the changed conditions impacted their interpretations and performances of the work as a final product. Despite the circumstances, the production team was thrilled with the outcome, recognizing the performance as a unique product of its time, and voicing appreciation for the ability to utilize uncommon settings and the beauty of nature as part of the narrative.

Divided into seven acts, the film event honed in on individuals, duos, or divided groups of dancers, seemingly socially distanced. Soloists and distanced group dancers interacted with artistic objects, representative of various burdens one might carry, while duos interacted only with one another, portraying various relationship complexities and the burdens that attend.

…the dancer contemplated it, dragged it, entwined herself in it, and attempted to walk while bound by her affliction.

Each solo act honed in on a single dancer, interacting with objects in a tangible representation of human hardship. The first, Emma Morrison, appeared in a verdant

landscape as she related to and struggled with an incredibly long, seemingly endless, artistically rendered “burden.” Sewn from many lengths of different colored fabric and evidently filled with something heavy, the prop resembled a Burmese python as the dancer contemplated it, dragged it, entwined herself in it, and attempted to walk while bound by her affliction. The second soloist (David Flores) appeared in front of a warehouse at night, attempting to pick up and carry a myriad of colored sandbags, lifting one after the other in order to take with him. The ceaseless struggle of picking up bag after bag, bearing their weight, attempting to carry them elsewhere, then only to have one fall, then another, and then another, was difficult to watch and felt painfully authentic.

All three duets seemed to cast light on different types of human relationships, each in its own unique stage, with unspoken intricacies between the two people. The first duo appeared passionate and lustful, yet timid and reserved at times. Close-up person to person contact, combined with the natural landscape and stunning cinematography, created a sense of intensely personal sensuality and exclusivity. The second duo portrayed a more weathered relationship, undoubtedly with history and baggage, but with maturity and contemplation. Rather than looking for the world in one another, the two were stretched out on the forest floor in repose, facing outward in the same direction, pondering the concerns of life together. The final duo characterized a more platonic friendship, filled with love and devotion, yet not without disappointment and hurt. Unexpected combinations of movements channeled quickly changing emotions, ranging from jagged confusion and resentment to flowing warmth and adoration.

The two ensemble numbers, despite appearing in disparate landscapes, functioned similarly in spacing, with each dancer relegated to six feet away from any of the others. The first group number involved each dancer wearing a large sheet of black fabric, wrapped about their body and limiting their range of motion. Over the course of the act, the film brilliantly captured the unlikely landscape combination of greenery and black tarmac, the overarching feeling of unrest and discomfort, and each dancer’s individual relationship with their black burden.

The final act featured the largest number of dancers of any movement, positioned six feet from one another, each enclosed by a snake-like, multi-colored art prop, arranged in a circle around their area. With each dancer wearing a unique, brightly colored outfit, the group of movers stood out against a stark, rooftop pavement scene, devoid of

nature or greenery. As the camera panned and re-focused on smaller groups or independent dancers, each dancer seemed to choose from a library of movements suited to or chosen for their character. One flowed endlessly from one new movement to the next, while another performed a sequence on repeat. Some moved with extroverted emotion, attempting to interact with the world around them, while others looked inward, ignoring outside factors and expressing restrained, introspective affliction. Upon observing the dancers individually as well as in combination, a spectator cannot help but begin to identify on a personal level, watching each character battle their own demons, surrounded by the blunt landscape of concrete structure, yet the vibrant color of human existence.

Jana Harper’s vision for this work came to life with the assistance of movement and assistant director Rebecca Steinberg, composer and musician Moksha Sommer, and filmmaker Sam Boyette. Steinberg’s originality and adaptability to a film setting brought an intimate, confidential feel to the movement of the work, highlighting the strengths of each dancer and utilizing existing relationships to re-imagine multi-person numbers during a time of separation. Sommer’s original score brought warmth and interest to trying subject matter, highlighting sounds of nature in and amongst electronically programmed and live instrumental music. Boyette’s videography beautifully captured the energy, emotion, and depth of each dance number, combining all seven movements to create a captivating work of art.

The collaboration that took place in order to create and carry out This Holding: Traces of Contact is a moving reminder of how unified and connected we have the power to be, whether together or apart physically. Recognizing the burdens that unify us is just another means of learning how to move forward together. Perhaps Harper got her wish—after watching this performance, one can feel only gratitude and hope, knowing there is strength and power in shared experiences with others, trials and tribulations included.

From the Pedestrian Bridge:

Chatterbird Performs Honstein

Down Baby Down by New York composer Robert Honstein (b. 1980) is a piece for percussion quartet in six movements. One imagines that the composition process started with the composer making a comprehensive list of noises that can be produced with a cello before unceremoniously crossing off “use a bow”. The piece, which runs just over 20 minutes, features cello, desk bells, woodblocks, and (what appears to be) 18 gallon storage bins with kick pedals attached. Taps, knocks, dings, booms, slaps, plucks, and hums are used intermittently as the performers mirror each other’s movements across a table adorned with a myriad of small percussion toys.

The piece develops slowly, but attention and interest is earned through an ever changing landscape of sounds and textures. The video, featuring Chatterbox’s Jesse Strauss, Maya Stone, Celine Thackston, and Aaron Walters is well performed, well shot, and well produced. Downtown Nashville and Cumberland Park serves as a background for the recording. An extra layer of interest is added by imagining the curious looks the quartet undoubtedly received from bachelorette parties finding their way to Broadway over the walking bridge in the video’s background. It’s a fun time! Check it out here: https://vimeo.com/415016631#at=1190 or on the homepage of their website: https://www.chatterbird.org/ or just click below!

Down Down Baby, by Robert Honstein from chatterbird on Vimeo.

At Oz Arts Nashville

New Dialect Performs Poignant Double Feature

Six amorphous figures appear on a dark stage as music fades in. The figures split into pairs and slow dance as the lights go up. It’s the kind of slow dance that you see in movies. The kind of movies where it takes an hour, a break up, and a triumph of the will before the two main characters, in a high school gymnasium turned Sadie Hawkins dance floor, realize that they were meant for one another. The girl rests her head on the guy’s chest as they share – if only for a moment- completeness. This is how First Fruit, Rosie Herrera’s new ballet, opens, the only caveat being that each of the characters are covered head-to-toe in Post-It notes.

Grants from the N.E.A., the Tennessee Arts Commission, Oz Arts, and the Danner Foundation made this world premier possible. In January of 2020 Herrera conducted a week long workshop with 67 participants from across the country. In the weeks following she collaborated with the dancers of New Dialect to create First Fruit; the the first of two works on New Dialect’s program last weekend at Oz Arts Nashville.

Warm and familiar-sounding Spanish music serves as a soundtrack while the neon squares of paper dance from the performers to the floor. Soon enough the stage, which had started black, is littered with bright colors. As layers shed from the dancers, bright street clothes and leotards are revealed. It is difficult, with a work of this nature, to nail down a specific and concrete meaning, but the performance is broken into roughly four main movements. Each scene seems to explore different endings to romantic relationships: heartbreak, drifting apart, abuse, and lasting love (in no particular order). One memorable scene features a female dancer who slowly and methodically rips a fallen post-it note to shreds. A male dancer, on the opposite end of the stage, writhes in agony with each motion. The end of each scene is heralded by the company rushing out and using a cardboard flap to cover a character (or characters) as they lay on the ground.

The integration of the post-it notes as costume, prop, and set is brilliant. The choreography itself is inventive in that it is always subservient to the narrative. The production runs a full gamut of emotion. It is quirky, sad, strange, beautiful, passionate, and mesmerizing.

The second production of the evening was The Triangle by Nashville Native and founder of New Dialect Banning Bouldin. This work, which played to sold out crowds last year, is a visceral and emotional study on our cultural obsession with overcoming. In a pre-event discussion she described this work’s unique creative process. Bouldin, a sufferer of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, described her first attack as the catalyst for this work. “3 and a half years ago I experienced my first episode of MS. I spent the first 36 years of my life an advancedly coordinated, athletic, professional dancer… I woke up one morning unable to feel my legs. I had tremendous difficulty balancing and walking. It was a very scary time for me. I Remember crying when I was sitting in my car and realized I wasn’t going to be able to drive myself… and having the very reassuring thought that I don’t have to be able to walk and I don’t have to be able to dance to make dances”.

Bouldin’s experience with MS opened a line of questioning which led to the development of 13 short works that she calls “Limitation Etudes.” She describes The Triangle as a natural outgrowth of these ideas. Confinement and constraint play a major role throughout the work. It opens on an ensemble of dancers connected in a maze of straps. As one dancer escapes she does so at the expense of another. At times it is difficult to watch; paralysis is an uncomfortable thought. The dancers found themselves confined to chairs. They are limp and powerless as the hands of others drag them across the stage. They fall and struggle to get up, and that was the most moving part of The Triangle for me. However difficult it was, they never stopped striving to get up. The dance is an artistic statement about our societies’ romanticization of striving that resonates far beyond physical disabilities.

This stint of shows will launch New Dialect into a three year touring initiative of these productions. They were one of five Southeastern dance companies to be selected by SouthArts to participate in the program. These works will continue to have life and meaning in other towns and communities as New Dialect acts as a cultural diplomat for the Music City across the country.

the Nashville Symphony

Beethoven and Genius: an Interview with Maestro Guerrero

This weekend, February 20th through the 23rd, Nashville Symphony will present an all-Beethoven concert, including the ground-breaking Eroica symphony, the somewhat confusingly titled Leonore Overture No. 3 (one of several written for Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio), and the classically oriented Piano Concerto No. 1. The concert is dedicated to the 250th birthday of the composer, which will occur in December of this year.

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 in Eb major, often spoken of fondly as the Eroica, short for Sinfonia Eroica (“Heroic Symphony”), marks the transition between music of the Classical era and the beginning of the Romantic era. Beethoven built upon the musical foundation of his predecessors, synthesizing the styles of Mozart and Haydn while innovating in virtually every facet of the classical symphony; form, harmony, dynamics, and emotional content are all expanded upon.

Fidelio is Beethoven’s only opera, though he did compose a number of overtures for it in an effort to set the opening scenes as effectively as possible. Leonore No. 3 is actually his second attempt, and though widely considered the best as a piece of music, audience members found it to be overwhelming compared to the relatively light scenes at the start of the opera. The Piano Concerto No. 1 is the earliest of the three compositions, and thus the influence of Haydn, and especially Mozart are clearly heard here. Yet Beethoven’s voice is unmistakable and his mastery of the classical forms of Sonata and Rondo undeniable.

This past Monday I had the honor to speak to Maestro Giancarlo Guerrero who will be conducting this weekend.

Jack Marlow: Good morning Maestro.

Maestro Guerrero: Hello, how are you?

JM: Very good, thank you for taking this time out of your schedule, I really appreciate it. So we are going to talk about Beethoven, my first question, kind of a nebulous one, but what do think Beethoven means to us today, why is he relevant in your view?

MG: Well you know the same things that inspired him in the early 1800s, in terms of passions and politics and love, depression, and challenges in one’s own life have not changed in human beings, so I think there’s a deeper connection. When we listen to not only Beethoven, but all great composers, going back hundreds of years, their music sends a message that is very much relevant to today’s world. In many ways we are able to understand what are the things that truly inspire us. Really he is no different from artists nowadays who are writing things that are almost a time capsule of the times in which they are living.

I promise you at that point, that is my favorite piece on the face of this earth.

JM: Right, thank you. Time for an easier question, do you have a favorite piece by Beethoven, any instrumentation, piano or-?

MG: You know what, it’s really whatever I am conducting at the time, to be honest with you. That is one of the questions we get asked the most as musicians, that’s almost like asking which is your favorite daughter or son. In many ways the best answer I can give you is whatever I happen to be working or conducting at the time. And the reason is very simple, you have to remember that we program our seasons sometimes two or three years in advance, so there is a kind of long gestational process of preparing the piece, getting it ready, deeply analyzing it, so finally you get in front of an orchestra and an audience and you’ve been waiting three or four years sometimes to get the piece done, so I promise you at that point, that is my favorite piece on the face of this earth. Because then when it’s over, it may be a long time before that piece comes back again, so it’s like spending time with a dear friend, and then you hope you get to spend time with that friend again in the future, and sometimes it can be another five, ten years, or maybe never, you never know how these things work.

JM: Yeah I feel that way just as an audience member. I’m a huge fan by the way, I go to every classical series concert I can. Why these specific pieces? It makes sense, with the Eroica, but why the first Piano Concerto?

MG: A lot of it has to do with scheduling, over the last few years we have done the other four concertos kind of recently, and the first it’s been almost nine years. So a lot of time it just kind of comes down the scheduling, which pieces make it into a program. One reason this program came together is that I wanted to showcase three aspects of his writing. In the case of Leonore 3, this was written for his only opera Fidelio, and then his piano concerto is basically the standard for piano players – they master each of the five. And then in this case the scheduling helped narrow it down to the first one. Then the Eroica, to me it’s been a while since I’ve done it, since I believe my first season here in 2009. So it’s a piece I haven’t done myself in a while, and I wanted to bring it back, and in many ways this is the one symphony that basically shattered the existing ideas of classical structure in classical music- traditions of music that were left by Hadyn and Mozart. Beethoven broke it immediately with this one piece and in many ways this one symphony is the starting point of what became the Romantic period. No slow introduction, just two very big, loud chords – I’m sure it must have been very shocking to the audience, and to this day it sounds very fresh. And plus the political inspiration of this piece that originally was written for Napoleon, Beethoven was a big admirer of the ideals of the French Revolution – equality, democracy and so on. So when Napoleon declared himself emperor, Beethoven became so enraged that he actually ripped off the title page, removed the dedication to Napoleon, and instead dedicated it to the memory of a great man.

JM: Fascinating.

MG: Remember that during the time Beethoven was writing this, during the Napoleonic wars, he himself had to deal with bombings from the French, they bombed Vienna during his lifetime. So these were very turbulent political times. And in human history those are always around, so in many ways this piece represents a time capsule of the turbulent political times that were being lived through in Europe at the time.

JM: Right, thank you. Possibly relevant to our own times. How many times have you conducted the Eroica?

MG: Once. Can you believe that?

JM: Wow-

MG: I’ve only done it once, and if you were to ask me why, I couldn’t give you an answer. Many of these things just fall off on the side, without any reason. I mean we have to go through so much repertoire every season, that every now and then it takes a moment for you to say “hang on a second, why haven’t I done this piece in a while, I love it.” So the fact that we have this birthday, this is the opportunity. Really doing it now – there’s a part of me that feels a little guilty. It’s been such a long time, and not for any particular reason. It just never came around, not on my radar, but now I promise it is very much on my radar.

JM: Have you learned anything specific in the score, details perhaps that didn’t jump out last time?

MG: Oh of course! Always, you know there’s always new editions coming out, new scholars that come out with new information, revised, and further exploration of the manuscript. Like any other great piece of music, great piece of art, it’s a living organism, these things evolve over decades and centuries. And we have to keep re examining them with fresh eyes and fresh information. Plus you have to remember I am not the same person I was ten years ago. So I’m looking at this from a very different perspective of a person who has been with the orchestra for more than ten years, and my kids were very little, and now I have teenage daughters – of course that’s going to affect my music making! How could it not, like when you read a book the second time you see different things because you’re basically a different person. So for me it’s always exciting because I get to know an old friend and love them even more. A lot of the things we find out have to do with logic – sometimes there is some ambiguity with things like articulation, or dynamics, and when you study the pieces further you apply logic – you almost have to guess really, like CSI Beethoven_ I’m trying to figure out what they were writing. Even now with computer programs that write music, like Finale or Sibelius, they are not perfect. I do enough world premiers to know even modern pieces have some ambiguity. So imagine two hundred years ago these people were writing with ink and pen, smudge all over the paper by candlelight – of course there’s going to be mistakes. So it’s up to us to use the best of our abilities to figure out exactly what it is the composer intended. In some cases, the worst part of it – there is a very fine line between a bad mistake and something brilliant. Whether the composer was going for something very unique or it’s just a mistake – there’s a fine line. It’s the same fine line between crazy and genius. So a lot of times you are forced to make what I call executive decisions.

…to be a genius at that level… I think there has to be a certain degree of madness

JM: Genius is an interesting one to discuss, you could think of Beethoven as the man that pioneered and really popularized that concept in the western imagination. Do you think genius exists and did Beethoven have it?

MG: Of course it does! But as I said, to be a genius at that level… I think there has to be a certain degree of madness associated with this. Because you’re seeing the world, I believe, in so many different layers, they have the ability to process information in a way that most normal people don’t have. By the way Beethoven was not by far the first, we could go back to Da Vinci, Michelangelo, we could go back to Mozart. These were artists and human beings that left such a mark that even to this day we are in awe at the things they did. Because as I said they process information and put it into their own art or artform , and it’s simply astonishing. When you think about the amount of work these people left – in many cases a very short period of time, and without the comforts of modern technology that we have nowadays. I think it’s just a complete miracle. And for those of us who do this, for me in particular, I find it incredibly inspiring and it’s a wonderful excuse to walk away from the craziness that is the 21st century with its fast-pace. When you get to sit down with a work that’s forty-five minutes long, and really delve into the mind of a composer, that like most of us had great experiences but also inner demons. All of that is seen very clearly in his art, and the same could be said of Mahler, Stravinsky, Mozart Van Gogh, Picasso, and any other great artist to this day that is making us reconsider the meaning of life in many cases.

JM: So you mention Mahler, Stravinsky – it’s kind of hard after the death of Stravinsky to think of a leading composer of the 21st century, the Beethoven of our time if you will. Who would you say is that person?

MG: To me, John Adams. He is by far the most performed music composer on the face of this Earth. And so we can go by that, John Adams has been able to find, I think, a following, while he’s alive he’s been able to enjoy great success, that even Beethoven would have wished to have, or Mozart. So there are some that I think have continued to set the standard, but he is not by far the only one. Think of Penderecki in Poland, or Philip Glass. I think what you are describing is that since we have such access to information right now – well back then the composer had a more slow recognition time because it took sometimes years for us to hear the pieces that were premiering in Europe to get to the United States, or vice versa. Nowaday when a piece gets premiered in Berlin we are able to hear it immediately. So that creates a much bigger pool of composers for us to pull from. There’s just so much easily accessible music immediately on our phones.

JM: With the Eroica, the 19th century is often framed musically as a debate between the programmatic and the absolute, Wagner versus Brahms and so on. Do you hear the Eroica as a programmatic piece, and if so do you have a kind of story or program in your mind?

MG: Well remember that the original inspiration for this was Napoleon, and the ideals of the French Revolution. There’s a degree of anxiety that came along with something so shocking in the history of Europe. The French revolution – I mean there was great fear among the monarchies of Europe because this was the beginning of the end for them. And of course as usually happens with big political upheavals all of the plans and works that the people promised, none of them came to fruition. I mean that is always the case, they always promise the wonders of the Earth, and then at the end the reality is that the personalities take over and usually it becomes a problem, a dictatorship. So the fact that Beethoven thought of Napoleon and the French Revolution experiment – you can hear that in the music, that he was feeling alongside everyone in Europe. Even if the composer did not intend to write something about something in particular, how can they separate themselves from their own personal lives? Whether it’s something associated with love, or in the case of Beethoven personal challenges, realizing at the time he was becoming deaf. All of these things must have an impact. So I don’t think there is a thing called absolute music. Even Mozart, who may have written 41 symphonies – everyone of these works were written at a time when something was happening in his life and this must have had an impact.

JM: I’m no Beethoven scholar, but I know there’s somewhat of a controversy about his original tempo markings, and I was wondering what your thoughts were about that.

MG: Yeah well it’s not so much of a controversy, what happened is that Beethoven knew Mälzel who invented the metronome. And as you can imagine the first prototype of it was not perfect. And we now know that the metronome Beethoven had access to was not quite precise. So a lot of scholars will tell you that some of the tempo markings, all of them if you ask me, seems a little on the fast side. But then again, it’s hard to say for sure. What we do know is that after getting the metronome Beethoven was so excited to have a new toy, that after the fact he started putting metronome markings on all of his pieces. He wanted to test his new machine and see how well it worked with his works. There’s been I believe two or three recordings of the Beethoven cycle recently where the big selling point is “oh we’re using the Beethoven markings.” Well you know what, they don’t work in some cases, sometimes they are just over the top fast, and you don’t get to really appreciate the music because it’s moving too fast. Beethoven was a master of the inner voices, and if the music is going too fast you miss out on the intricacies in the middle. Even the most demanding composer in my lifetime has never told me “it’s 72 to the quarter note, and it has to be 72 to the quarter note – “ Never! Every single one of us as conductors or performers have to put our own personal stamp on it. For me these metric markings are more of a starting or reference point. What’s more interesting though, to me, is the relationship between the movements. 120 in the first movement, 60 in the second movement, you know the second was intended to be half as slow. To me that is much more interesting than the number itself. Because the number was dictated by the acoustics of the hall, the virtuosity of the orchestra, and the personality of the conductor.

JM: Right, checks out to me at least. Last question: what do you see as the future of classical music in general, and in Nashville specifically?

MG: We are living in an incredible time of access to information. Orchestras these days are absolutely incredible. Nashville Symphony is a world class, virtuosic orchestra that can tackle not only the challenges of Beethoven or Mozart, but also the great challenges of recording live the music of our time from living American composers. I truly believe that orchestras need to continue to reach out to their communities. It is our responsibility in Nashville and in the rest of the world, for orchestras to service the people that live in those communities. Orchestras really should enrich the quality of life of the communities that they belong to. And Nashville is no different, I’m very proud to belong to a city that is proud to call itself Music City. And there is so much activity – great quality world class music activity happening in Nashville. The symphony needs to remain relevant, we need to remain a part of that environment, of what makes Nahville important So far us, it is all about servicing and bringing music to our community and making sure that this music has relevance in what is happening in Nashville. We just really have to think about – what you program in Nashville should be very different from what you program in New York, very different cities. A big part of it is really trying to keep your ear on the ground and figure out what Nashville needs from the Symphony. And as long as you do that you’re always going to have music lovers come and continue to support it. And remember this question was also being asked around Beethoven’s time, “what is the future of music?” Things haven’t changed, Beethoven was new, Mozart had world premiers. This is nothing new. The question that continues to be asked is making sure that the music we play has a place at the table, and that people feel a connection to it personally and spiritually. But we have one of the best concert halls on the face of this Earth so that helps a lot.

JM: Well I can speak for myself that I love Nashville’s programming, I’ve learned a number of new composers I had never heard of, and I’ve gotten to enjoy some standards – I’ve never gotten to experience the Eroica live so I’m really excited for this weekend.

MG: Sweet. You know, it’s funny this actually is a really unusual program for us – Beethoven, a one composer program, and he’s dead, so kind of unusual program for us.

JM: Can’t wait to hear it, thank you for speaking with me Maestro, have a great day.

MG: Thanks so much Jack, take care.

I am confident that Maestro Guerrero will have the depth of knowledge and the personal warmth required to bring out the best of Beethoven’s music, Nashville is fortunate to have the chance to see such a skilled conductor and orchestra perform some of the best music composed in such a beautiful concert hall.

Nashville Ballet

Blurring Ballet Lines: A Series of Moving Dialogues on Gender Identity and Stereotypes

Does movement imply gender? Do accepted norms impact freedom of self expression? Is creativity subconsciously limited by culturally-imposed stereotypes? These are the types of questions choreographers Carlos Pons Guerra, Erin Kouwe, Matthew Neenan, and Jennifer Archibald grappled with in Nashville Ballet’s production of “Attitude—Other Voices.” As cultures, expectations, and expressions shift over time, this type of artistic commentary uniquely provides a tangible interpretation of human struggle and progress.

“Private Balls,” choreographed by Carlos Pons Guerra, provided a wonderfully curious, yet poignant perspective on the desire to dance together, specifically with someone of the same gender. The piece portrayed countless elements of what desire looks and feels like, but no movements were depicted in an overtly sexual manner; rather, the array of emotionally charged gestures conjured feelings of incredible beauty, melancholy, longing, hesitation, relief, and wonder. With a variety of romantic and post-romantic pieces provided by the accomplished and sensitive Alessandra Volpi at the piano, the dancers portrayed an inspiringly non-traditional narrative against the underlying conventional ballet music.

Contributing to the personal-feeling storyline of the ballet was the enchanting, innocent voyeurism that attended the costume collection of the dancers. The all male-presenting cast of characters wore an eclectic collection of undergarments ranging from boxers, undershirts, vests, briefs, and dress socks, to long-sleeve silk shirts, gauzy tops, bow-ties, and cummerbunds. As each pair danced together, the language of movement exhibited an array of feelings between the couples: love, humor, passion, wistfulness, freedom, and security among others. As the narrative unfolded of one particular dancer facing his own desire to dance with another, the audience moved through the journey with him, experiencing the breadth of movement-invoked emotions along the way. Guerra’s choreography juxtaposes quaint charm with emotional gravitas, intimating out-of-reach experiences and emotions for an audience hungry for understanding.

Erin Kouwe’s “Auto Poet” elicited a much more philosophical response to gender roles, cast with all female-presenting dancers in a variety of pure white, androgenous apparel. Kouwe described the process behind the piece in her choreographer’s notes: “Our work began with individual hyperlogic: each dancer moving toward the desire of their own method of physical thinking. We pulled apart the threads of that logic, slowed it down, observed, and defined it in order to know the desire that made it. Does the desire embedded in our logic reveal any subtext about who we are? … The limitations feel at once arbitrary and powerful. Pulling apart the threads of limitation and desire led us into chaos and closeness.”

With insight into the cognitive origins of this piece, the choreography is immediately recognizable as a reflection of that process. To the untrained eye, movements are combined in such a way as to seem random yet matter-of-fact, focused yet chaotic, angular yet graceful, and pieced together in a strange yet beautiful way. Perhaps due to the movement choices, but also influenced by Louis York’s original music, the piece took on a sense of contemporary, authentic beauty, highlighting unrestrained expression in an intellectually provocative way. Kouwe’s compelling language of expression deconstructs boundaries, inspiring curiosity and awareness.

Matthew Neenan’s “There I Was,” with a lush yet minimal, emotionally integral score composed by Christina Spinei, was born out of the choreographer’s own experiences with loneliness. Highlighting a career spent surrounded by fellow dancers yet constantly feeling alone, Neenan captured the internal battles fought by questioning gender expression in the ballet world. With contemporary artwork by Vadis Turner suspended from the rafters above the stage and intriguing costuming providing stark contrast between vibrancy and shades of gray, Neenan’s large-scale choreography of a 25-person cast wove all elements together into a work of emotionally affecting grandeur.

Following the main character, portrayed by company member Brett Sjoblom, the audience was drawn into an emotionally-wrought journey of questioning, gender exploration, alienation, denial, torment, resolve, and recognition. Sjoblom’s interpretation and characterization of this role conveyed an intimate, passionate, and unlimited understanding of Neenan’s choreography, communicating emotional fervor in every step, bend, and gesture. The use of such a large cast added an incredible depth to the overarching message of the work, portraying a wide array of human experiences and emotions, banding together in the end en masse, seemingly seeking the same thing collectively: acceptance.

“Posters,” with choreography by Jennifer Archibald, original music by Louis York, and poetry by Caroline Randall Williams, served as a dialogue about womanhood and re-claiming feminine-associated stereotypes, characteristics, and experiences. Archibald notes about her creative process, “I have focused on the women, and the untold experiences that women may or may not choose to share. To take gendered norms and re-conceptualize, reclaim and subvert them in ways that are active, self-governed choices is empowering.”

Beginning with all black, simplistic costuming, male and female-portrayed dancers interacted in smaller groups of twos and threes, enacting experiences in which the women’s actions were dictated, expectations were set, or specific reactions were assumed. Archibald’s choreography reflected each female figure’s internal struggle, movements suddenly shifting from compliance to conflict and back, jarring the audience’s understanding of each interaction. With Louis York’s songs titled “Raging Bull” and “You and I,” a sense of uncomfortable unrest began to build, eventually arriving at a passionately charged dialogue reflecting the relationships on the stage.

With intermittent spoken word by Williams, the music continued to grow, swelling with up-beat, soulful, world-inspired sound as dancers one by one appeared in a new black and yellow costume and a brightened outlook, changing the narrative to one of empowerment and joy. Each couple now moved with equal intention, seeming to support the other without any expectation, definition, or assumption. Louis York’s song “Posters” embodied the message Archibald chose to champion in the piece, defying all cultural impositions and seeking to redefine womanhood in whatever shape it chose to take. As the final work and program came to a close, the audience responded overwhelmingly with genuinely appreciative applause and a standing ovation, smiles inspired on faces and hope instilled in hearts. Nashville Ballet’s decision to commission new ballets on such a culturally relevant theme was a timely and exceptionally welcome one, continuing to cultivate an audience eager for inspiration and artistic commentary for an ever-changing world.