At the Darkhorse Theater

The Crucible

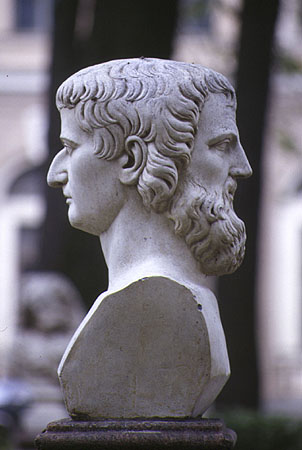

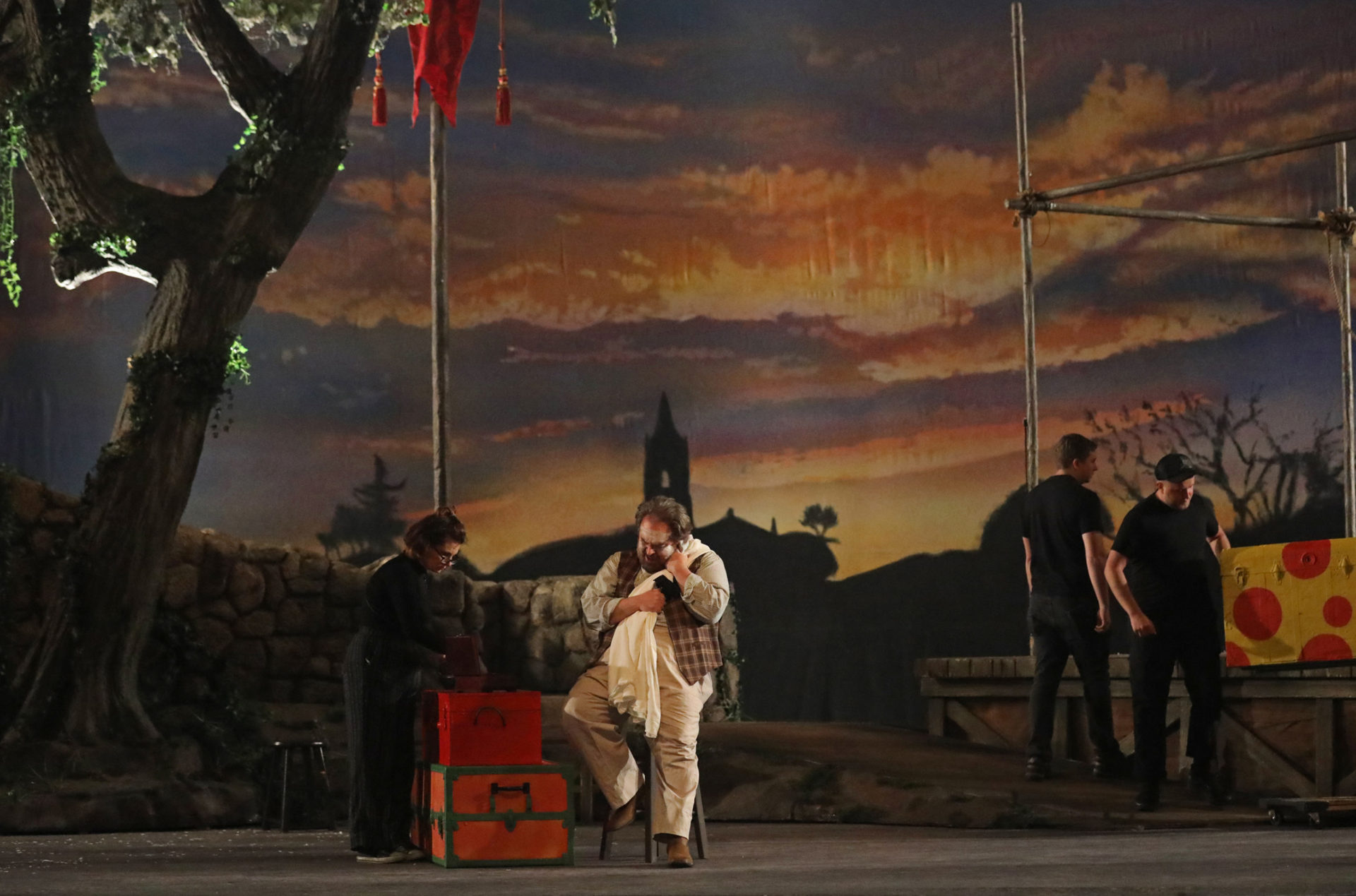

Elite Studio Works performed The Crucible, Arthur Miller’s play that is permanently on the nose in the best possible way, portraying the archetypal witch-hunt. Written in 1953 as a response to McCarthy’s anti-communist hysteria, it’s about the Salem Witch Trials. The play’s meaning is not limited to 1692 or 1953, but contains truths about hysteria, blame-shifting, and the willful blindness of authority, that are true in every place, age, and setting. It showcases individual and societal flaws and temptations that can break into damaging action when the situation presents itself. Sometimes the safety of external blame leads to a domino effect. Director E. G. Bailey’s note in the program said, “A play like The Crucible should put our society under a microscope. It should feel uncomfortably familiar, full of characters that feel recognizable in people you know, people you’ve seen on television, and maybe even in yourself. It should invite its audience to look introspectively and truly ask yourself what you would do in a situation like this. In this play, no one is the villain, yet everyone is the villain– from the protagonist to the by-standers.”

Elite Studio Works performed The Crucible October 13-21st at the Darkhorse Theatre. The location is quickly becoming a favorite of mine. Located in Sylvan Park, it’s a brief walk from tasty restaurants (my friend and I ate at M. L Rose just two blocks away) and has Richland Park’s parking lot right across the street. The theatre is small but comfortable and every seat has a good view. The tickets were $25 with general seating and the water bottles only cost $1.

This was the first performance of the Elite Studio Works I’ve seen, and I was highly impressed. Their acting is quality. This long, dense, emotionally fraught play was performed with such palpable emotion that they had me pressing my arm against the wooden armrest of my chair out of tension; my arm was sore the next day. Abigail Williams, the teenager who starts the blame game in an attempt to kill the wife of the man she loves, was played by Alaina Bozarth. I liked the way she portrayed the character; she didn’t try to act creepy the entire time, although she certainly was creepy by the end. She brought naive bad-girl vibes; the sort of high-schooler who brags about shoplifting, drinking, and flirting with teachers. She felt more selfish than malicious at the beginning, and that she was slowly shrinking into the role she had made for herself.

Audrey Venable played Mary Warren excellently. The nervous girl, always on the outskirts of the trouble, plagued by guilt and fear, and without the strength to be fully bad or fully good, felt so real, and her nervous trembling while being shouted at in the courtroom were tragically pitiful. John Proctor was played by Michael Adcock with exactly the character that Miller describes in the play: “He was the kind of man– powerful of body, even-tempered, and not easily led– who cannot refuse support to partisans without drawing their deepest resentment. In Proctor’s presence a fool felt his foolishness instantly…” His role, calling for a balance of guilt and rightful discernment, was played with excellent emotion and not a hint of self-pity. Dustin Davis played Reverend John Hale, and was my favorite character. The clergyman who comes to look for witchcraft had the delightful vibe of a pediatrician; the one who is hopeful, clear, but doesn’t lie and tells you when things will hurt. His growing distrust in the entire witchhunt, and his disillusionment and grief for the part he played in it were somehow the most emotional for me. Who hasn’t been very sure of the way things work, has acted accordingly, and then later realized the actions had only hurt people?

Adapted very slightly, Elite Studio Works’ performance was set in 2045, “where religion rules the law of the land. Democracy is now dystopia.” Paradoxically, this timeless play is very specifically dated. The language is Miller’s beautifully real-sounding old-timey speech, women are called “Goody,” men hold all the power, they live off of pre-industrial farming, mention battles with Native Americans, and are Puritans. This cannot be shifted to a different setting the way Shakespeare’s plays so easily (and often helpfully) are. The vaguely rustic dystopia felt more like it was set in the Fallout video game franchise: a metal trashcan held a fire, old tires leaned against a wall, with vintage objects and a record player. Like Fallout, the soundtrack was pre-1950’s music. That part I enjoyed; I assume most productions of this stick to heavy-handed ominous instrumental music. Costumes were slightly inconsistent; plain suits, John Proctor had a old-fashioned rustic look (rather like Daniel Day-Lewis’s costume in the movie adaptation), a few dresses, but most women dressed in high-waisted pants with crop tops. I think either Puritan attire or some more modern interpretation with drab uniformity would have more seamlessly integrated with the nature of the play, although some of the variety helped clue in people’s characteristics.

The only other aspect of the play that I think detracted was the casting of a woman for the role of Deputy Governor Danforth. The heavily patriarchal power dynamic of the Puritan town felt undone slightly; the vengeful use of the teen girls’ only taste (or hope) of power through using their bewitched condemnations of others seemed less plausible when the most powerful character in the play was a woman. Plus, they kept the script the same, so it felt a bit off when these Puritan fundamentalists kept calling the woman in heels “sir.” Lindsey Patrick-Wright, who played the role, did a fantastic job portraying a bureaucratic authoritarian who confuses her role with that of pure, abstract justice and refuses to even consider the possibility of mistake, condemning the suggestion as an affront against the notion of justice.

Elite Studio Works chose an ambitious play and pulled it off with spirit and skill. The most impressive thing about the performance for me was the consistent quality of their acting across the cast, and the way scenes were kept fraught with tension. The moment when all the girls feign that Mary Warren is cursing them in the courtroom was well done and genuinely creepy. I’m sad that I was only able to attend their penultimate performance; I wish I could encourage readers to attend this show. This was their final play for the year, but the back of the program announced 5 Women Wearing the Same Dress and Frost Nixon as their 2024 season. For more information, see Elite Studio Works.

The MCR Interview:

Fable Cry’s 9th Festival of Ghouls (Interview with Zach Ferrin)

As part of the MCR Interview series journalist Bethany Morgan asks Zach Ferrin about his upcoming performance at OZ Arts with his band Fable Cry, as part of the 9th Annual Festival of Ghouls celebration.

About Town

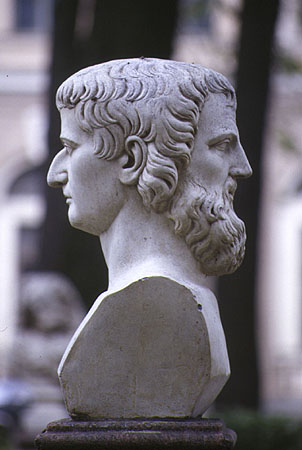

Nashville Film Festival

The Nashville Film Festival celebrated its 54th year this fall: six days of over 140 films; panel discussions and live performances; a competition; a conference; all held at eight different arts venues in Nashville, as well as online at the Nashfilm Virtual Cinema. Needless to say, we couldn’t possibly begin to cover everything shown at this Academy Award qualifying festival, especially as we also covered the International Black Film Festival, which occurred here in Nashville at the same time. Our writers did their best to divide and conquer. We saw shorts, documentaries, and dramas, attended red carpet events, and viewed the online catalog.

Black Barbie

Written and directed by Lagueria Davis, this 100 minute documentary details the creation of black Barbie while also delving into deeper issues of race and prejudice. Davis was inspired to tell this story by her aunt Beulah Mae Mitchell’s work at Mattel. Mitchell, a well-spoken and charismatic woman, makes the viewer feel as though they are in the room with her enjoying a cup of coffee and talking together. She explains that when she was child, there were no black dolls for her to play with. She recounts working for Mattel and meeting Kitty Black Perkins who designed the first black Barbie in 1980. Perkins is also interviewed in the documentary and she shares how she came up with idea for the design and the hair and how she felt as a woman of color in this company. Davis also interviews Stacy McBride-Irby who worked for Mattel under Perkins, and then later created the 30th anniversary black Barbie. She tells us how she really wanted to make dolls that looked like her daughter.

Intertwined with these interviews are interviews with people of color, exploring how childhood play helps to shape our current reality and what it feels like to never be the main character in their own story. Davis shows footage from a recent study, in which children were asked to look at a group of diverse Barbies and identify the “real” Barbie. They all choose the blonde, white Barbie. This study was inspired by the 1947 doll studies by Clark and Clark. Davis includes a heartbreaking clip from Kenneth B Clark describing how black children associate positive attributes with a white doll and negative attributes with a black doll. This study played a significant role in Brown v. Board of Education, which overturned state-sponsored segregation in the United States.

At the core of this documentary is a cry for change. While some real steps have been made toward equality, we are far from where we need to be. Davis points out that the 40th anniversary black Barbie was created by a white man. In a book created by Mattel that chronicles important moments over the years, they leave out the creation of black Barbie in the year 1980. The animated Barbie movies and show all focus on white Barbie who sometimes has a black friend. Mattel, and society needs to do better, to allow children of all colors to experience themselves as the heroes of their own story.

-B. Morgan

Music Video Shorts

The Music Videos shorts collection was an exhilarating experience from psychedelic to hardcore, to classical. The collection is marked, like the pop music genre it represents, by a combination of new and old, the innovative and the vintage.

“Minor Setback,” sets to film a 7” single by Aussie super-duo Ambrose Kenny-Smith (King Gizzard) and Jay Watson (of Tame Impala) which came out back on Record Store Day (April 24). The video features orange men in a museum with an abundance of hand-painted film and 3D animation, especially during the bridge. Jake Armstrong’s animation is spot on. The video is quite reminiscent of the Dire Straits’ “Money for Nothing” in its colors and affection for animation, and in that way it is strangely vintage and futuristic at the same time. For what it’s worth, “Minor Setback” is a much better song than “Money for Nothing.”

Thomas Nyffeler’s “Mio” features a naïve composer’s daydream of meeting a beautiful woman with similar interests and forming a relationship over the music. The cinemaphotography of the Swiss landscape is remarkable, and the dark, almost noir depiction places us in the context of a 20th century European War, but the music and the narrative lack any real emotional depth.

David Heatley’s “Mess” features naked, kickboxing, punk chicks on roller skates with a hardcore “4 on the snare” rhythm. The animation is bright, aggressive, almost as aggressive as the song—it’s like a big glass of tart orange juice. Similar in Vitamin C content, but different, is Lovejoy’s “Portrait of a Blank Slate.” Busy as hell and right on top of the beat, driving a strange, new wave sound not unrelated to the White Stripes that they’re calling “pop-punk” these days, is Mark Boardman on drums. The video is a delightful setting of mid-20th century sci-fi film (think Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, or The Twilight Zone).

Named after, one guesses, the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, an influential and controversal “urbanist,” with “REM Koolhaus,” Kajo and his team of animators made me tangibly nostalgic for Liquid Television circa 1995; heck, it even includes a guitar-playing astronaut. The least derivative of the group, while it also deals with another love story (or better, a broken heart story) unlike Nyffeler’s “Mio,” “REM Koolhaus” encounters the challenges and emotional tribulations of “collapsing into the endless dark” of life, love and, perhaps, REM sleep. It’s a sweet, lovely video and composition.

The collection ends with the delightful “Broken Chain” by Midnight Mantra, filmed at the local Blockbuster. If Kajo was the least derivative, Cade Huseby’s is an etude on influence, taking us through a collage of turn-of-the-century (the most recent one!) blockbuster videos in which the lead character sees himself and his gal together. There is a lot of Quentin Terentino, but without the feet. It’s a cute entry, but not terribly memorable.

Overall, I think this was my favorite collection of shorts, and I’m certainly going to watch again next year!

-J.M.

Fingernails

I wasn’t sure what to expect from this unappealingly-named movie, but my lack of preconceptions didn’t prevent me from being surprised; it is a slightly dystopian sci-fi romance with a strong sense of humor. Where other sci-fi gets pompous, this gets silly.

Set in an alternate late 90’s, they reference the Spice Girls, have no wireless phones and an almost implausible scarcity of computers; besides a home TV and brief moment in a movie theater, only one screen features in the plot, part of a scientific machine. For a contemporary science fiction film, it is refreshing to avoid swooshy graphics, apps, and heavy-handed commentary on social media. It gives similar alternate-almost-present-day vibes as Apple’s Severance, and is more successful than it when it comes to costuming; I don’t want to live in the world of Fingernails, but I wouldn’t mind dressing as if I did.

The concept is fun: an objective third party can tell you if you and your partner are actually 100% in love. Have a fingernail removed, have your partner’s fingernail removed, and the machine can analyze them and give the results. The film is playful, but its point is clear: we as a society are all too ready to make drastic life decisions based off of new pop science, and are willing to submit to and suffer for ideas we haven’t fully considered. People sacrifice for duty and ideals, and we call that heroism. People sacrifice for their desires, and sometimes they’re praised and sometimes they’re condemned. What if people pay the experts to tell them what they feel, and sacrifice based on that?

The cast is marvelous. Everyone is fun to watch, not just because they’re attractive, but because they are charismatic and interesting. Jessie Buckley is charming as Anna, who starts working at the institute, partnered with Amir (played by Riz Ahmed), where they help prepare people for the test by putting them through days of exercises intended to boost their romantic connection. The exercises are comically corny: singing karaoke together in French (as Luke Wilson explains, French is the language of love), watching Hugh Grant movies, staring into each other’s eyes while underwater to prompt a feeling of connection and breathlessness. Jeremy Allen White as Ryan, Anna’s boyfriend, is excellent, and his portrayal of fatigue at the end of long days is incredibly relatable.

The movie is willing to be slow. Characters speak, think for a moment, then change their mind. This more realistic pacing makes for romantic tension while avoiding cloying tropes. The music helps with this, most of it diegetic, and each song well-chosen.

The flaw in this movie is that Anna, the main character, is rather unlikable when you think through her actions. If you ignore how endearing Jessie Buckely is, you see someone who tells a huge lie without plausible justification. To be fair, I have a hard time enjoying infidelity romances: as the film progresses, Anna’s attraction to Amir causes her to doubt her relationship with her boyfriend, and whether to trust her perception of her feelings, or the machine’s. Riz Ahmed as Amir is handsome and intelligent and adorably lonely (the attraction is obvious), but Ryan, her Mr. Wrong, doesn’t seem wrong. I appreciate that they avoid the typical rom-com tropes showing his unsuitability (usually displayed by liking sports or having a personal social life), but his only faults seem to be being tired after work and being a little stuck in routine. Maybe that could be enough, except he’s also shown to be forgiving and kind. Perhaps Jeremy Allen White is just too likable, or I’ve just been married long enough to know that there is romance in the mundane.

Despite its flaws, though, it is funny, has a great point, and is a pleasure to watch. I’ll watch it again when it comes out on Apple TV+ on November 3, and recommend you do so too.

-G. E. Tipton

Graveyard Shift Shorts

Murder Camp

Written by Will Lagos & Jeremy Radin, this dark comedy was my favorite of the Graveyard Shift Shorts. Cleverly written and well acted, the idea of a serial killer having an existential crisis is surprisingly fun. As he tries to convince a fellow serial killer that there might be more to life than killing, the argument gets heated. A college student taking psychology classes (and a potential victim) comes upon them and counsels them, later finding out that she identifies with them more than she thought. The ending is perfect for this silly slasher!

The Jennifer Meyers Story

This mock true-crime episode really impressed me with its ability to blend dark humor with some genuinely creepy moments. The interviews in the mock crime episode are interspersed with reenactments with crudely-made mini models. Some of the interviews have little pieces of humor and the mini models are sometimes silly. It becomes a bit meta as the woman operating the mini models packs them all up and goes home and we see that she is being watched. The dark, bloody ending is shown in mini model form.

Get Away

Three girlfriends vacation in the middle of nowhere: a classic start to a horror story. The characters are aware of this and joke that they are staying in a “murder house.” There’s no wifi and no cable, but the women find a VCR player and a tape and choose to watch that for their entertainment that night. The horror begins when they start interacting with the characters on the television and soon a static-y creature appears on the TV. As with any good scary movie, you’re rooting for the characters and yelling at them to get out. A good, although a bit predictable, twist makes for a horrifying ending.

Are You Awake?

In some alternate universe, a woman named Dale makes a living by waking up strangers. It is never explained why this is a job, and she must go into these people’s homes and make sure that they are awake. After an unsettling experience with a client who is plagued by nightmares, Dale also finds it hard to wake up. The actress, Ellyn Jameson, does very well with this character. You feel her boredom in the monotony of her job, and then her unease with her last client, and finally her terror as she navigates her own nightmares. While unsettling, the overall message of the short was a bit unclear, perhaps intentionally so, to allow the viewer to form their own conclusions.

Paragon

After an MIT student realizes the computer program he created not only can give him current facts, but also predict the future, he learns that there are forces that influence the future, and they are not to be messed with. The short begins as a psychologically scary film, as the student realizes his program is sentient and powerful. As it comes to a close, it changes to a monster type of horror as a creature comes to destroy the program. While the juxtaposition of these is a bit strange, it is very effective. The creature itself is scary enough to make you shiver!

-B. Morgan

The Unraveling

Darkly disturbing, Kd Amond’s horror/psychological thriller The Unraveling tells the story of Mary Dunn (Sarah Zanotti) after enduring a car crash that left her with a traumatic brain injury. The accident left her with an inability to recognize faces and look others in the eye. This film is remarkable in many ways, but perhaps most of all because of its efficiency. With a very small main cast of four people and a shadowy manifestation, the movie explores a gambit of emotions and concepts including paranoia, grief, sorrow, love (maternal and romantic), friendship, facial disassociation, and disability. Sam Brooks’ character Grayson is just likeable and charismatic enough so that you think you should trust him, except that you are watching a horror movie—from Mary’s perspective, the doubted authenticity of his character is the rub and the sine non qua of the movie.

Seth Dunlap’s cinematography is remarkable. The confining spaces Mary finds herself in, a visual for her psychological condition, and the arresting use of white in a non-positive way (a lá The Shining) contributes subtly and substantially to the film’s success and is well juxtaposed with the tar that haunts Mary. The jump scares are exquisite, and there are several of them, prepared well by David Lim’s sound design.

Exposition and character development are achieved through visits to a therapist, as Mary’s sense that everyone around her is an imposter grows. The final reveal is strong and surprising if a little predictable in that you know a reveal is coming throughout the movie. The setting, a large, old house, in which you can never really get your bearings, adds to the movie’s haunt, and is just another attribute of Amond’s economy. In a film festival that was remarkable for many independent films, this was the film that felt as though it was mainstream, and not art-house. One wonders what Amond will be able to accomplish with a Hollywood budget.

-J.M.

Comedy Shorts

Baseball With Dad

This is a cute story of a father and son connecting over baseball. The son proclaims that he hates baseball and his father insists that it’s in his blood and he will love it. Once the son hears how his grandpa used his special bat to knock a tornado away, he starts to gain an appreciation for the sport. It ends with the son grown up, now playing with his own son. Although the situation itself wasn’t particularly funny, I did chuckle at Cody McHan’s clever writing.

Eat It

This short follows a woman after a breakup as she interacts with her coworkers at a bowling alley. Feeling empty and sad, she fills the void by eating anything and everything she can, including: her engagement ring, carnations, and a live goldfish. She even enters a pie eating contest only to realize afterwards that she doesn’t need to eat to make herself feel better. The acting in Eat It was the best of all the comedy shorts. Shannon Woodward really made you empathize with her character and root for her to find healing after her breakup, all while making you laugh. The writing was creative and quirky in a way that made me want more than just 10 minutes. I could watch a whole movie devoted to the employees at the bowling alley.

Wake up

This little short is only 3 minutes, but it was still full of laughs. A robber breaks into a woman’s house only to realize that she is an amputee. After he sees that she only has one leg and a prosthetic leg stands at the edge of the room, he tries to leave without taking anything, only for the woman to protest that he is being discriminatory. The concept was unique and the writing by Sally Jane Pitts was clever and humorous. Despite it being the shortest of all the comedy shorts, it was my favorite.

Lac-Date

On a date in a restaurant that only serves milk-based products, a girl realizes she is out of her lactose medicine and enlists the help of her best friend. This over-the-top comedy is full of physical and slapstick humor. The best friend has to literally fight someone at the store for the last bottle of lactose medicine (my favorite part) and she arrives at the restaurant with a black eye. She then has to sneak around to try to give her friend the medicine covertly, only for the date to pull out a bottle and announce that he needs to take his lactose medicine. Lac-Date was such a wonderful, silly romp!

Horny Kid – A film essay

This short is a video of a conversation between director/writer Josh Whiteman and his mother. She is recounting some of his behavior as a child, like his desire for a life-sized Barbie and kissing Victoria’s Secret magazines. He asks his mother at one point if she thinks that he’s single because he never got that life-sized Barbie that he wanted. Because of his solemn demeanor, it is really difficult to tell if he was joking with this question. He then asks if she feels guilty for not getting him the Barbie. Again, he is so somber that it really seems like a serious question. I found his character unlikable and this was my least favorite of the shorts.

Sympathy for the Devil

In a new twist on an old tale, a man makes a deal with the devil in this short. The devil sits down with the man in a booth at a bar and asks if the McRib is back at McDonald’s. The devil offers to give him anything he wants only for the man to drone on and on about how he doesn’t know what he wants. The devil offers to let him take over as the devil, in a bargain that benefits them both. It ends with the devil enjoying a McRib. The writing by Michael Bentley and Corbin Eaton was quite good; a great blend of witty and silly. While the acting, also by Michael Bentley and Corbin Eaton, wasn’t quite as good as the writing, it was still a very enjoyable watch.

-B. Morgan

Time Bomb Y2K

Documentaries and based-on-a-true-story movies usually focus on things that happened, disasters or achievements. This documentary is about something that didn’t happen. I looked forward to seeing it because I was there for the event but was too young to remember it. For readers younger than me, the year 2000 problem, or Y2K, refers to the potential computer errors that could have brought down worldwide infrastructures because of a simple calendar data formatting system; years were stored as only two digits, making 2000 and 1900 indistinguishable. I had a nebulous understanding of this before seeing the documentary and was excited to actually learn about the whole non-event.

What makes the film especially interesting and impactful is that it is told entirely through archival footage; besides the fun animated opening credits, ending credits, and year markers, it’s all news footage, movie footage, even home video from donors (some of whom attended the Nashville Film Festival showing) and the Center for Home Movies. In a delightful Q&A after the viewing (the best I’ve ever been in: the host asked excellent questions and the audience asked through true interest and not a desire to perform) co-director Brian Becker explained that they had gone through over 700 hours of footage. The film took three years to make, beginning as a side project until getting grants and eventually ending up with HBO, where it will air in December. Sticking with pure archival footage brought difficulties; Becker said that it was difficult to find new pieces with introspection or emotion instead of straight delivery, and it would have been much easier to have a narrator than to hunt for the perfect line, but it paid off. I certainly agree; watching it is immersion in the times, and it avoids some of the tropes of typical documentary narration.

Becker said that he and co-director Marley McDonald were interested in American subcultures orienting themselves around existential threats, aligning Y2K with their belief systems and expanding upon it. In the film we see survivalists; militias; strange religious groups; entrepreneurs; Clinton’s President’s Council on the Year 2000 Conversion; mainstream talk shows; Matt Damon in an interview; and street interviews with everyday people. It feels balanced in its telling. Becker said the film was shaped by their research and that they didn’t set limits to it, but looked for stories that resonate with us today. Besides going through the footage, they interviewed many of the people who featured in the film: the only thing he and McDonald knew they wanted to do, going into the project, was have it climax at New Years Eve, which they both have childhood memories of.

The documentary is successful in its storytelling. It starts off in the early 90s and each year is a countdown to the Millennium, keeping the chronology clear and adding tension to the pacing. The music, done by Nathan Micay, sometimes feels a little heavy, but that’s the point: Becker said that they wanted to have an electronic 90’s sci fi/disaster movie sound. It’s easy to see what caused so many people worry; having experts warn of nuclear malfunctions because of computer glitches isn’t something most of us easily shrug off.

The film is comforting in an odd way. It’s easy to relate to people worrying about a much-touted potential collapse caused by technology, even when a lot of the footage is tragically funny, and many of the people are outrageous. Besides being a historical event that shapes our current culture, I think teens especially should watch this to give them some perspective on cultural fears and the fallibility of “expert” opinions. The film shows some of the baselessness of some Y2K fears, as well as what can be solved by concerted actions of competent people. The big fear was no big deal, but we are shown the difficulty of seeing that at the time, leading to empathy for the people who anxiously awaited the Millennium.

Timebomb Y2K is a good reminder that we forget the successes of life because bad news always marches to the front of our minds. We forget that the WHO eradicated smallpox in 1980, saving a potential 150-200 million lives since then. According to the UN, more than a billion people have been lifted out of extreme poverty since 1990. While we have many existential threats ahead of us, this film is a reminder that humanity has solved problems, even the ones we have caused ourselves.

-G. E. Tipton

Animated Shorts

27

I had some difficulty with this film as there were no subtitles and it was not in English, but the beautiful animation made up for that. The short follows a girl who has turned 27 and still lives at home. The audience watches as she dreams of escaping her current life. After crashing her bike, she has a sexual awakening that could be real or imagined (the subtitles may have made that clearer). Viewer be warned: it is explicit! Because of the language issue, I was really able to just enjoy the art. The large team of animators did a wonderful job: the art is vibrant and beautiful.

Christopher at Sea

Aptly named, this short tells the story of a young man who embarks on a transatlantic voyage as a passenger on a cargo ship. The trip is one of self discovery as Christopher forms a one-sided attachment to one of the workers on the ship. His attraction to the man borders on obsession as he covertly watches him through his camera, mirrors, and windows, imagining he can feel a connection with him through walls. The short ends tragically as Christopher goes out to the edge of the deck in a vicious storm, allowing the sea to embrace him, imagining he is in the arms of his unrequited love. The art in this short was so stunning, especially the way the artists conveyed the wind moving through the characters’ hair and clothes, and the way the waves jostled the ship.

Eeva

The audience follows a woman on the worst day of her life: the funeral of her husband. There is no dialogue, only the art and music to tell the story. There are moments of strange dark humor throughout the film. For example, a funeral attendant uses an umbrella to squash a woodpecker that has landed on her husband’s coffin. The wife is the only woman present in the story and it is clear that the sorrow of the day affects her differently than all the others. She doesn’t openly weep, but stands or sits stone-faced until she lets out her rage, throwing things and later setting fire to her own apartment. The art is unique and quirky: a muted palette of blacks, grays and browns, with pops of vibrant red, the red perhaps symbolizing her anger and passion.

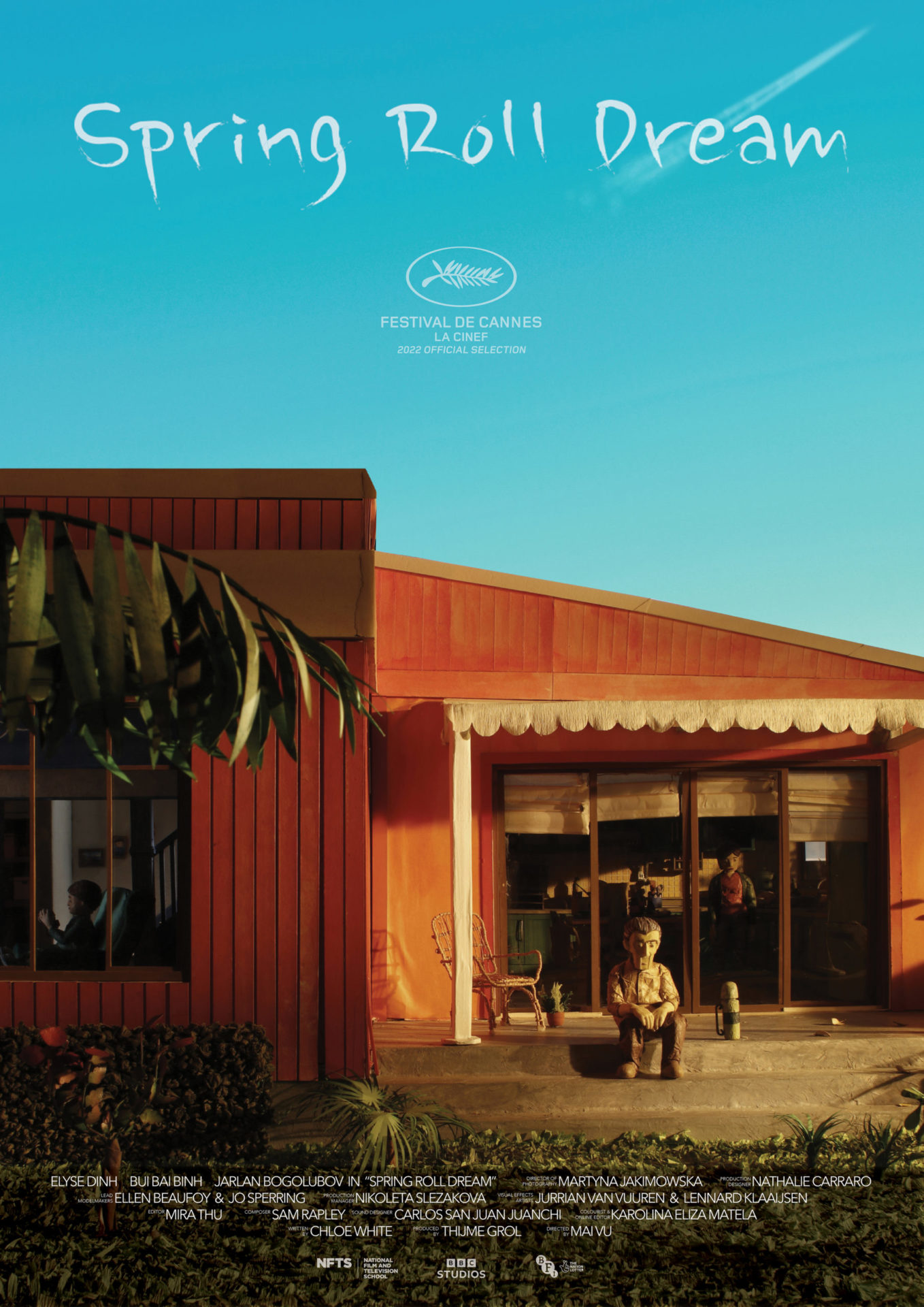

Spring Roll Dream

This was my favorite of the six animated shorts, and not just because it had subtitles for both the English and Vietnamese dialogue. It tells the story of a Vietnamese woman who has made a home in America and is struggling with her desire to be American as her father tries to connect her back to her roots. Her father has made spring rolls, but she insists that she is making mac-n-cheese and the she and her son won’t like the Vietnamese food. In a heartwarming ending, she tries and enjoys the spring rolls, and her son does too, putting ketchup on them. Her father even tries the ketchup spring rolls. Mai Vu is the sole animator, director, and editor. She does a phenomenal job, especially considering many of these shorts have a whole team of animators. A sweet story about the blending of culture, Spring Roll Dream leaves you with the warm fuzzies and a hankering for spring rolls.

Tomato Kitchen

Tomato Kitchen is an episode from the online animated series called Capsule Project, presented by Bilibili. This is a surprisingly dark short, in which the tomatoes in the restaurant are actually sentient beings that are being slaughtered for consumption. The past of the main character as a tomato that has carved himself to look like a person is revealed as he attempts to save others and destroy the kitchen. Taken at face value, the story is horrifying enough. A possible more terrifying meaning is that we all carve ourselves up, slicing off bits of our identity to fit in with society. The art is wonderful, mostly muted blues except for the bright red of the tomatoes and blood/tomato juice. Junyi Xiao does a phenomenal job fulfilling many of the roles for this film including: director, writer, lead animator, cast, and production designer.

Zidane Roulette

This is a sweet short about how soccer brings together a young boy and an adult who lives in the apartment above where he practices. After going out on the town for an unfulfilling night, the man takes out and fixes up his old cleats and ball, and practices, forming a friendship with the young boy. The art is very contemporary, and reminds me of something that might be on Adult Swim. Incredibly, Emy Mirel Ivasca fulfills every role in the making of this film, with the exception of sound design. I really enjoyed this endearing film about soccer and friendship.

-B. Morgan

Sound Stars in the Tuba Thieves.

Alison O’Daniel’s The Tuba Thieves brings together loosely connected scenarios through the unifying feature of tuba robberies, crimes that actually occurred in Los Angeles schools between 2011 and 2013. However, the movie isn’t about tuba theft, or sousaphones for that matter. Instead, it is a beautiful, if long winded, essay on, in, outside of, and around sound. The movie starts with a number of actors portraying deaf people, but after a piece, it draws your senses in when you begin to recognize the heightened role that sound plays in the movie.

As such, several aspects of the film were quite thought provoking. A group of deaf people are shown describing an airplane breaking the sound barrier. Later in the movie, we see images of a plane actually breaking the sound barrier (a white cloud is formed by decreased air pressure and temperature around the tail of the aircraft).

group of deaf people are shown describing an airplane breaking the sound barrier. Later in the movie, we see images of a plane actually breaking the sound barrier (a white cloud is formed by decreased air pressure and temperature around the tail of the aircraft).

However, during the conversation, the diegetic sound (birds, traffic, the gestures of sign language) becomes rather distracting, and, although obvious, it becomes readily apparent that conversation for deaf people occurs outside of sound. Yet the power of sound is also emphasized. For example, the impact of a new airport has on a neighborhood (houses are eventually demolished).

The film’s open captions (open captions because you can’t turn them off) particularly, are much more detailed than usual, and seem to shift with the character of the music (there are three cited composers of this film’s excellent soundtrack—Christine Sun Kim, Ethan Frederick Greene, Steve Roden). They describe the sound, the emotion of the sound, and even the length, as well as comments on the sound. In a world where captions can seem so negligent, or poor in their characterization of aural events, this alone should lead to an artistic revisioning of the caption as a long-neglected opportunity for expression in the cinematic experience. There are other overtly experimental aspects—at one point the plants begin to vibrate with the non-diagetic music. For once the aural becomes the source of the expression and the visual relegated to mimicry.

Other remarkable scenes include a reenactment of the premiere of John Cage’s 4’33 in August of 1952, at the Maverick Concert Hall in Woodstock New York. In the scene you see the pianist start a stopwatch, sit down in front of the piano and close the lid (4’33 is a piece that requires the performer to not play a single note). An audience member (the irritated man, Norman Aaronson) ducks out and wanders into the woods where he removes his shoes and seems to have a sylvan epiphany. Another scene documents (the artist formerly known as) Prince’s performance at the famous Gallaudet University (a university for the deaf) at the height of his career.

There are a couple of parallel narratives that are unwound across the film that are rather difficult to follow or see how they relate. Nyeisha Prince’s character “Nyke” is a deaf person who is interested in percussion, and Prince plays her character with no short measure of charisma and grace. Russell Harvard’s “Nature Boy” is a character with a bit more depth and is played with a strong clarity. His reading of visual poetry, even symbolist poetry, in ASL was remarkable. Geovanny Marroquin brought a youthful resilience to the film and Manuel Castandeda played a pretty realistic band director (probably because he is one). Another aspect of the film that was hard to follow were all the messages on the high school signs.

O’Daniel, who is deaf herself, seems to have placed a lifetime worth of experiences and revelations regarding sound into the movie. They reveal, quite powerfully at moments, things that are otherwise taken for granted. I am quite interested to see her work on a topic not quite so personally connected to her own life. In all, The Tuba Thieves is a thought-provoking piece that challenges the viewer. It is an important and an intriguing view, but it certainly isn’t light.

-J.M.

Conclusion

This is just a taste of what the Nashville Film Festival had available this year, not only to filmmakers competing in hopes of getting their Academy Award consideration, or for aspiring and working filmmakers to attend showings and events to learn from their heroes and peers, but for the general public. Cinephiles and regular people who love going to the theater but are tired of superhero movies can get access to rarer titles, or see films long before they’re posted to some streaming platform requiring a new subscription. We at Music City Review enjoyed our coverage and are looking forward to next year’s festival!

At the Schermerhorn

Ruth Reinhardt’s Debut at the Nashville Symphony

This past Sunday afternoon the Nashville Symphony gave a concert that waffled between breathtaking moments and another average night at the symphony. As the audience settled into their seats, a recording of Béla Fleck asked us to turn off our cellphones in this “sacred” space. The word “sacred” seemed, to me, an interesting choice. As I looked around the half empty concert hall, (or was it half full?), I did not feel a particular religious weight to the moment, but I was hoping that the music would be able to wash away the stresses of the week.

On paper, this concert program looked intriguing:

Grażyna Bacewicz: Partita for Orchestra

J.S. Bach: Keyboard Concerto in A Major

Jessie Montgomery: Rounds for Piano and String Orchestra

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 1

The first three pieces, which had never been played by the Nashville Symphony before, were each about 15 minutes in length, and the Bach and Montgomery featured Awadagin Pratt on piano. What stuck out to me about this program was that it featured pieces from the 18th, 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. Instead of a single large concerto, we would hear Pratt in the oldest and newest pieces. In reality, the program came off as a little stiff with no real unifying structure.

Bacewicz’s Partita for Orchestra was the most intriguing and perplexing piece on the concert. It is laid out in a compact four movements – each with a conventional title: “Preludium”, “Toccata”, “Intermezzo”, and “Rondo”. To me each movement felt like someone had dropped the needle on a record into the middle of a full symphony. Ideas started and ended quickly, with little time for development. Like eating a multi-course meal in a matter of minutes, I wish the piece was longer so that I could savor each moment as it came. The Nashville ensemble gave a fine reading of the piece under conductor Ruth Reinhardt, although it was new to them. The years of playing and recording new music made reading this piece not a challenge, but I wanted a bit more musicality out of it. Was that the fault of the piece or the performance?

Following the Partita came an unintended semi-intermission: the audience lights are brought half up and the conductor’s podium descends into the depths of the Laura Turner Concert Hall to remerge with the piano. The whole process takes several awkward minutes, and it always kills the energy in the hall. Eventually, the orchestra meandered back onto the stage and Awadagin Pratt emerged to start the Bach.

Bach, one of the Mt. Rushmore composers, is always interestingly played by a modern orchestra. Originally written for a small string ensemble and a harpsichord, this performance featured Mr. Pratt on a Steinway 9-foot Concert Grand Piano and most of the symphony’s string section. It is hard to strike the right balance of style on modern instruments, but the playing was quite magnificent throughout. The slow middle movement was the closest we got to something sacrosanct all afternoon. Pratt’s playing was sensitive and light in all the right spots. There were a few spots that Pratt wanted to add some nuance to the music that I feel did not completely come out, making those moments feel less like communal chamber music and more like a struggle between the soloist and ensemble.

Following the Bach was Jessie Montgomery’s Rounds for Piano and String Orchestra. This was originally written for Pratt as the soloist. Pratt served as a commissioner of six works for orchestra and piano that was assembled into an album called “STILLPOINT”, with the Montgomery serving as the opening track on the album. Rounds is aptly structed as a rondo, where the opening music cycles back multiple times in between episodes of varying music. Pratt’s pianistic ability was better on display in this piece – the jazzy main theme danced under his fingers and every time it returned I was more entranced by it. Pratt made music magic in the middle section of this piece. It is an extended section for only the piano with some parts that call for improvisation. Pratt showed off the full range of colors in his playing, including a section where he stood and stroked the wires inside of the lid of the piano while one hand still played on the keyboard. Extended techniques like this can sometimes come off as a parlor trick, but not here. The effect was both musical and added to the richness of the piece.

After the intermission the full orchestra came out for Brahms’ First Symphony. What is not to love with this piece? Here both Reinhardt and the Nashville Symphony seemed most at home. The strength of the famous opening was terrifying in Reinhardt’s hands and yet the second movement was deliciously sweet. Based just off the quality of the sound that the group was able to make, this was some of the finest playing that I have heard from the Nashville Symphony in a while. It never ceases to amaze me that a piece like this that is over 150 years old can still seem so fresh and relevant. But when you have a conductor and an orchestra aligned in their vision so clearly, well written music will always have that effect. That effect was not there for the first half of the concert, but it was in full force for the Brahms.

The Nashville Symphony is back at the end of the month Giancarlo Guerrero conducting a live recording of John Corigliano’s Triathlon and Respighi’s Pines of Rome. For more information and tickets please visit NashvilleSymphony.org

MCR Profiles:

Stanley Yates, Guitar

How did a working-class boy from a twelfth-century town, who survived an early life of personal and parental illness and foster homes, end up with stunning accolades for international performances, for over twenty published works, and with a decorated doctorate from a university in Texas? And how did a largely self-taught young man from the North of England end up here, a highly accomplished hidden treasure in the South of the United States? On a Sunday afternoon in September, guitarist Stanley Yates and I had a delightful and far-ranging conversation.

Technical perfection, tonal purity and a considered objectivity are all

perfectly placed

(Den Bosch, The Netherlands)

Stanley Yates chose the guitar at the age of twelve for the loftiest of reasons: his best friend got one, so he got one, too. As an asthmatic child, he often missed school, but his early education in music and movement and singing in school assemblies fused with memories of seeing the Beatles from nearby Liverpool on TV, watching Disney’s iconic Fantasia, and listening to classical music on radio and in motion pictures, enhanced his musical foundations.

His skill on the guitar progressed so quickly that he was already in the midst of the first stage of his performance career when he entered university in Liverpool. Liverpool is often painted as a bleak backwater port town, but Yates remembers it as a vibrant city with its own bohemian section, a city that had acknowledged and moved forward from its history as a slave-trading post and its historical relationship with Yates’ home in Preston, Lancashire, which once housed cotton mills.

He started his university education with an eye toward a physics major, but his blossoming music career urged him on in the city where he met his wife. On and on he performed, delighting in the opportunity to share his zeal for music with audiences all over Europe.

...instinct and brilliant technique with the most refined musical and

musicological preparation

(Milan, Italy)

Once, during a set of performances in the U.S., his wife’s birthplace, Yates performed in Dallas. The head of the guitar program at what is now known as the University of North Texas was in the audience. Afterwards, Yates—then in his thirties and beginning a family—began to discuss a more stable existence than as journeyman recitalist. The head invited him to consider the doctoral program with a full fellowship. And at that, the second half of his life began.

Putting performance on the back burner, he completed his studies, and was hired as a professor at Austin Peay. Financial necessity initiated the second stage of his performance career, the stage he refers to as “super professional”: doing lots of concerts in lots of venues to earn lots of money. Combining experiences from his travels with his teaching, he began to amass notebooks of ideas filling hundreds of pages. Those notebooks, compiled approximately ten years ago, launched the third stage of his career as pedagogue, because he has always enjoyed “getting ideas down in a comprehensible fashion.”

He sticks to the grade better than any other anthology I know …. includes a lot of

less well-known repertoire … [that] are a real pleasure to play.

(Classical Guitar Delcamp)

Performing, though still an active part of Yates’ life, became more selective. Two of the most memorable venues were in Brazil, with own its rich history of guitar music, and Bangladesh, where Western music was virtually unknown. During this period, he thoughtfully alternated between publishing arrangements of music in great demand, like Bach and Vivaldi, with editions of lesser-known historical figures (Francesco Carulli) and anthologies of modern composers (Štěpán Rak). He sees his highly regarded two-volume set, Classical Guitar Technique from Foundation to Virtuosity as writing “letters for myself when I was 16.” As we dug deeper into his motivation, it became clear that Yates takes great satisfaction in advocating for his instrument and its repertoire. “We don’t have 32 Beethoven sonatas,” he notes, but points out the guitar’s greater breadth of strong repertoire with virtuoso pieces dating from the 16th-century, long before the piano existed.

…a phenomenal achievement, a worthy successor to the great methodological authors

of the guitar.

(Graham Wade, Classical Guitar Magazine)

As a parallel to his own three-stage career, Yates categorizes the guitar’s evolutionary stages as starting in the Renaissance when plucked string pieces were written by players, to the “second Renaissance” of the guitar when non-guitarist composers with strong reputations like Manuel de Falla and Igor Stravinsky began to write for the guitar. Now, one of his most recent anthologies features the third Renaissance where respected performers like Leo Brouwer, who are also highly trained as composers have raised guitar repertoire to new heights.

It is nice to have music from contemporary guitarist[s]… it is fun to try new ideas…

I am very glad I got this.

(Amazon)

In his upcoming program, Yates traces guitar history from a lasting figure of the English Renaissance, John Dowland. Dowland, whose melancholy demeanor led to the epigraph: semper Dowland, semper dolens [Dowland is always down], was a loyal proponent of Catholicism in opposition to the Church of England, founded by King Henry VIII. It’s interesting that Preston, Yate’s hometown, also fought to maintain its Catholic roots, becoming one of the last holdouts to the C of E. These days, Preston is better known for its soccer stadium, the world’s oldest in continuous use.

Dowland’s famed Lachrymae [“Flow my Tears”], a slow dance known as a “pavan,” survives as one of the greatest hits of its day continuing its influence on musicians like 20-century composer, Benjamin Britten, who quoted the tune; as recently as 2006, a British electronica group did as well.

Yates’ musical memoir of pivotal moments in guitar history will feature works by de Falla, Villa Lobos, Brouwer, complemented by two works by innovative Czech guitarist-composer, Štěpán Rak. He also plans to play Fernando Sor’s last solo guitar work, Fantaisie élégiaque in E major, one of his perennial favorites. This extended multisectional work includes a funeral march dedicated to Charlotte de Beslay, one of Sor’s students whose talent had attracted the attentions of such luminaries as opera composer Gioachino Rossini. Sadly, she died in childbirth.

Since Yates sees his career as a performer winding down, this elegy may be symbolic of more than just the mourning of a valued student. Everyone is encouraged to enjoy this internationally acclaimed artist at the historic First Presbyterian Church (213 Main St) in Clarksville TN at 3 pm on October 22, 2023. The concert is sponsored by the Clarksville Arts and Heritage Council. Admission and parking are free. For more information, contact: Laurina Lyle at Laurina@Laurina.co or ahdc@artsandheritage.us.

From Nashville Ballet

Ups and Downs: The Nashville Ballet Tackles Mourning, Rabbits, and Stravinsky

The filmed introductions provided an attractive opening to the Nashville Ballet program this past weekend (Sept 22–25). Each intro featured someone deeply engaged in each of the three works. In the case of Jiří Kilyán’s, Un Ballo, this was Shirley Esseboom, his assistant or repétiteur (the person who rehearses the dancers in place of the choreographer); for Justin Peck’s Year of the Rabbit, stager Michael Breeden praised the NB’s athleticism and their youthful “go for broke” spirit; for the featured work, Firebird, Director Emeritus, Paul Vasterling, introduced his own work.

These personalized touches gave the audience more intimate glances into the process of preparing for ballet performances. However, one remaining issue is the fact that none of the soloists or duo dancers are identified. All the orchestra members are named by instrument, so if there is a good bassoon solo, like that in the “Berceuse” section of Firebird, I can congratulate Julia Harguindey for the poignant bewitching beauty of that solo. However, if I want to spotlight the pas de deux couple in the fifth part of Year of the Rabbit? Out of luck.

That distancing undermines the intimacy. For those who appreciate the company and want to share in the journey of its growth, it’s only fair to keep the names with the quality of work. As the dancers evolve in technique and interpretation, how can we track that evolution if they are not identified? Just a thought.

***

The dark, bare stage was lit from above by strands of evenly spaced lights. In a glancing touch at mourning, women in black camisole tops with full skirts, men in black pants and dark grey vests, danced, one couple after another, to the somber prelude from Ravel’s Tombeau de Couperin. This music was written as an homage (a tombeau is a memorial work) not just to the great French baroque composer, François Couperin, but to those French soldiers who died during World War I.

The second, larger part of Un Ballo, used another Ravel homage, Pavane pour une infante defunte [Pavane for a dead princess], a work thought to be inspired by Diego Velásquez’ “Las Meninas,” a painting that includes Princess Margarita as a child. She later died in childbirth at the age of 22. The pavane, a processional dance for long rows of couples, was popular throughout Europe throughout the 16th- and early 17th-century. In fact, some graduation processions still use a version of it.

In this work, Kilyán, internationally recognized director of the Nederlands Dans Theatre and winner of the Edinburgh Critics Award, uses couples doing identical, albeit modern, steps, suggesting a subtle reference to the original pavane. These sections, though, exposed a continuing discontinuity in the Nashville Ballet corps. When steps are identical, there seems to be no agreement on where the beat might be. It seems clear the choreographer intended that some gestures, like slowly raising one arm upward should reach the apex at the same time. Here, as in other works featuring the corps, the movements suggest the dancers have learned the count, but are not actually hearing the music. The coordination of the corps de ballet deserves more attention.

Interestingly, two lovely aspects of the choreography paired with the costuming shone through. In one, the women raise their skirts to form a backdrop, much as one might see in Kabuki drama. Such an imaginative move focuses audience attention on the individual dancers. Another had the dancers lifting their partners upside down. The women’s skirts draped over the men, rendering them invisible, as each woman’s legs slowly pointed heavenward, with one positioned a bit to the fore, creating an elegant piece of choreographic sculpture.

This concept, one Breeden identifies as “architectural design,” is also found in Justin Peck’s choreography, Year of the Rabbit. With music by rock electronica artist Sufjan Stevens, skillfully arranged for string orchestra by Michael Atkinson, Peck’s work was able to hit the sweet spot in the Nashville Ballet’s technique. Tony Award winner and resident choreographer for the New York City Ballet, Peck’s work sparkled as brightly as the playful, though sometimes intense, sounds from the strings.

The attractive well-executed male solo in the second section, the section that ends with the sculpture of some dancers upright, while other dancers descend into slow splits and, in some spots, accurately placing gestures with the appropriate musical accents. This shows that the company can connect with the musical rhythm under the right circumstances. Perhaps the driving rock rhythms contributed to this successful connection. After the corps scampers away, the sixth section features ritualized dancing that may pay homage to Stravinsky’s Sacre de Printemps [Rite of Spring], except in Peck’s world, the frenetic quickness and deft skill, traits associated with the Chinese Year of the Rabbit, exude dance, not of death, but of delight.

Firebird

I came prepared to enjoy this work more than any other, having seen this music performed last in 2014 when the New York City Ballet revived the original Balanchine/Stravinsky/Chagall production of 1972. I understood that Vasterling would be re-envisioning the classic tale known in Russian, Czech, Armenian, and Iranian cultures, but still, this was a disappointment on many fronts. And, with a few exceptions like the principal bassoon and percussion, even the orchestra felt below its usual energy level.

The opening seemed static, sluggish, until evil takes the stage. The intention of turning this well-traveled tale into a morality play where the original Prince Ivan becomes Everyman, torn between good (Firebird) and evil (Mr. K, known in the original as the demon Katschei) is a valid one. And even making good and evil apparently equal in power made sense, but pairing them at the end with a narrative that suggests romantic attraction didn’t work. In fact, it seemed constructed to give the Mr. K character a more prominent role than the narrative supports.

In fact, more focus and choreographic pacing seemed to go into the evil K-crew than the magic of the eponymous Firebird, giving much of the best work to the bad guys. Both their costumes and their choreography were much more dynamic. For example, it was exceedingly clever to dress Mr. K in a business suit with slicked-back, con-man hair, accompanied by his sidekicks Miss P and Mr. D in equally deceptive costumes of the poisonous pretty girl and child-snatching ice cream man, respectively. Dressing the rest of the demon gang in a beach scene as Stepford wives in red polka dots and husbands in 1920s-style striped blazers was delightfully thought-provoking, and appropriately eerie as these dancers in “people” clothes often made reptilian movements, like quick jerkings of the head or undulating the spine.

But that’s what made the Firebird costuming so disappointing. It was not only lackluster in bland green with the panels of glittery material, but looked cheap, lacking the magic of a fairy tale whose popularity has traveled half the globe. I kept thinking of the years of ballet recitals I attended for a young relative.

The bare set and the plain costumes of the good guys undermined the magic of the tale, although the opening with Mr. K on a dark stage with the purple-hued diamond spotlight was one effective moment. The ending was also partly effective with all dancers dressed in beautiful sheer tunics with floral appliqués as the sun rises triumphantly, but again the equal prominence given the Firebird and Mr. K seemed misplaced.

The sizeable audience at the Polk Theater in TPAC was an appreciative one, which this generally fine program deserved. With more specific program information indicating the overall timing and sections of the works, perhaps the audience’s enthusiasm could be better channeled so that multipartite choreographies would not suffer from interruptions by misplaced applause. Next up for Nashville Ballet is the annual, can’t-miss holiday event, the Nutcracker, beginning December 8. More information is available here: https://www.nashvilleballet.com/nashvilles-nutcracker-2023