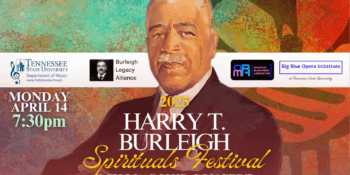

Burleigh Spirituals Festival Scholarship Concert

On Monday April 14, a lovely gift was shared with a rather sparse, but welcoming audience. Since 2016, Patrick Dailey has been Nashville’s leading force in preserving and honoring the legacy of Harry T. Burleigh who was, himself, a leading force in both preserving and honoring the legacy of African American spirituals. Burleigh (1866–1949) was one of the earliest classically trained American composers to arrange black spirituals for the concert stage. His arrangements were heard worldwide.

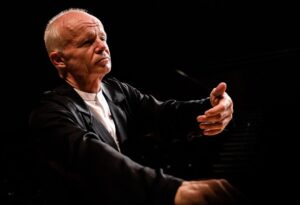

Dailey, world-traveling countertenor and part of the voice faculty at Tennessee State has worked with a broad variety of musical allies to produce this annual event. Each year there is a slightly different variation based on the same theme. In 2023, when the annual event was held in the Country Music Hall of Fame, connections were made between American roots music and spirituals. This year’s event, held in the Laura Turner Concert Hall, made connections between Jazz, Gospel, and spirituals. One thru-line was the performance of spiritual arrangements by African American composers, like Moses Hogan. Another thru-line featured both choral and solo works.

The printed program did not name specific works but, instead, divided the evening into five segments: first featuring six Nashville Opera HBCU Fellows; then HBCU choirs; the awards section; features by the guest artist, Damien Sneed; and finally, excerpts from Duke Ellington’s wondrous Sacred Concerts.

Excellence blossomed throughout the evening. Two students delivered standout performances among the interns. From TSU, Brooklyn Cook’s pitch, enunciation, and delightful stage presence worked well for her musical theater piece “Mister Snow” from Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Carousel. In a very different style, singing “Steal Away,” Fisk University’s Anna Sims exhibited subtlety in dynamics and timbre. Both clearly understood the assignment required by their respective works.

The HBCU choir section likewise shone in differing styles. The TSU Meistersingers, directed by three-time Grammy nominee Jasmine Fripp, have clearly mastered the more traditional college choir techniques of blend and solid presentation. Lane College’s Jennie E. Lane Ensemble, directed and performing a piece composed by Assistant Professor Alexis Rainbow, a graduate of the Cleveland Institute, displayed a vivid style that fused African call & response elements with the wailing elements of African American spirituals. The audience response was notably enthusiastic. Again, both groups and their directors were true to their roots, clearly understanding the necessary excellence such performances required.

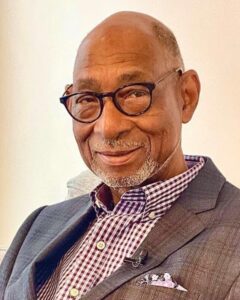

The Burleigh Arts Trailblazer and Burleigh Civic Champion awards were presented to Darryl G. Nettles, interim chair of the TSU Music Department and Lorenzo Washington, founder of the Jefferson Street Sound Museum, respectively. Both recipients were obviously moved and well-deserving.

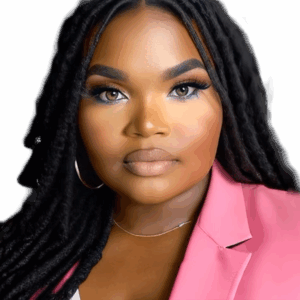

World-famous artist and current host of The Bobby Jones Radio Show, singer Bobby Jones introduced the featured artist of the evening, Damien Sneed. This section of the program, alone, should have filled the hall. Sneed, winner of Dove and NAACP awards, collaborated with San Franklin, Alysha Nesbitt, and Dailey bringing the house down with expertly performed “Tell Me It’s the Truth,” “Praise God,” and “Come Sunday” from Duke Ellington’s Sacred Concerts, a sophisticated fusion of jazz and gospel. Franklin’s saucy performance delighted the crowd while likewise, Dailey, most widely-known for his performance of 18th-century Baroque music, revealed a little-known, but well-developed skill for scat singing.

My favorite part of this well-wrought program, however, featured the TSU’s Jazz Collegians—yet another well-trained student group with tight performance and excellent soloists in the trumpet, trombone, and sax sections. They were well prepared by Professor James Sexton. Ellington, whose career overlapped substantially with Burleigh’s in trying to expand the reach of black spiritual music, came at this goal from a differing angle. Like Burleigh’s works that have reached canonic status, Ellington’s soul-stirring Sacred Concerts deserve more performances like these solo and jazz combo excerpts.

In the future, I hope the administrations of the schools and organizations involved with such events will engage more vigorously. When students get a chance to perform at one of the region’s premier locales, upper-level administrators could well get college buses to bring faculty and students as support in the audience. And allies like Nashville Opera and the Nashville Symphony could encourage more of their audiences to support such worthy events. But, regardless, those who attended experienced a wonderful treat, and for students to witness and take part in such an event cannot help but have a lasting impact on their growth as musicians.

Kudos to Professor Dailey (founder of the Big Blue Opera Initiative), Kellee Halford (Executive Director of the Nashville Black Music Association), the Burleigh Legacy Alliance who funded the Sneed’s appearance, and all those who contributed to treasuring Burleigh’s legacy. Proceeds from the event support the NBMA’s Harry T. Burleigh Fund for Vocal Studies. One additional piece of good news: Next year’s tenth-anniversary event will be held in Burleigh’s homebase Erie, Pennsylvania celebrating at the home of one of the world’s most active Burleigh organization, the aforementioned Burleigh Legacy Alliance.

Broadway at TPAC

Mamma Mia!

It was quite the packed night at TPAC. On March 18, 2025 at 7:15 pm, the air was both alive and electrified. In my time as a music journalist, I don’t believe I’d ever seen TPAC so busy. I took my seat—K3, all the way to the right of the building—and I was surrounded by a sea of voices, as eager for what was to come as I. Strangers, mostly women of all ages, made easy conversation with one another; from what I could eavesdrop, about weekend activities, church, and, of course, Mamma Mia.

The lights dimmed, and the performance began softly, with Sophie (Amy Weaver) confessing to her best friends that she’d invited her three potential fathers to her upcoming wedding, without her mother’s knowledge. Her lyric soprano voice carried beautifully over strings and woodwinds, especially through the seamless set transitions; they bled into each other so well it was as if I were watching the movie. Sophie’s vocals were beautifully contrasted with her mother Donna Sheridan (Christine Sherrill’s) much deeper, richer alto voice as she sung of her former flings all returning for her daughter’s wedding.

As someone who admittedly hadn’t seen a Mamma Mia production in years before this night, I had very little prior knowledge on what I was walking into. But from the beginning, with this performance, it was made clear this would be a non-issue. All characters and their relationships to one another were introduced with clarity, and the storyline remained easy to follow. Among classic ABBA tunes like “Dancing Queen,” “Honey Honey,” and “Voulez-Vous,” the cast blew their way through the musical in an astonishingly rich and deeply humorous fashion. Tanya (Jalynn Steele) was my personal favorite. Her rich alto voice and acting truly stole the show; she’s both the fierce independent woman I can relate to, yet also running away from every man who chases her.

If I had to praise one aspect of the show above all others, it would absolutely be costume design. All the outfits, from Sophie’s wedding dress, to Tanya’s glamorous sunglasses and scarves, to the fathers’ suits, camping gear and much more, were all spot-on. They sparked a 70s atmosphere to the stage, while keeping it contemporary at the same time. It’s one of those rare, beautiful timeless aspects to an art that are difficult to come by, but was done so perfectly here at this packed TPAC night.

Mamma Mia shone its timelessness, in the audience, voices, setting and costumes. I highly recommend the show, and while their time at TPAC is over, you can find out more about their tour here.

From the Nashville Repertory Theatre

Sunday in the Park with George

I had been looking forward to this show since they’d first announced it. Sondheim! Sunday in the Park with George won the 1985 Pulitzer Prize for Drama (one of only 10 musicals to do so). I won’t go into deep analysis of the musical itself; there are many excellent resources on this work, both online and especially in James Lapine’s book Putting It Together: How Stephen Sondheim and I created Sunday in the Park with George. You can also watch the PBS American Playhouse version with most of the original cast on YouTube and elsewhere. Except for a brief summary of the musical, I will focus my review on the Nashville Repertory Theatre’s production.

In the past few years I’ve seen the Nashville Repertory Theatre do many excellent musicals with the typical clear-cut separation of dialogue and individual songs. Sunday in the Park with George, however, has lengthy stream-of-consciousness songs with interspersed dialogue, complex rhythms, challenging vocal demands, and talented musicians. You can’t accomplish this show casually or half-heartedly. The Nashville Rep did it with complete dedication. It was an impressive and successful accomplishment.

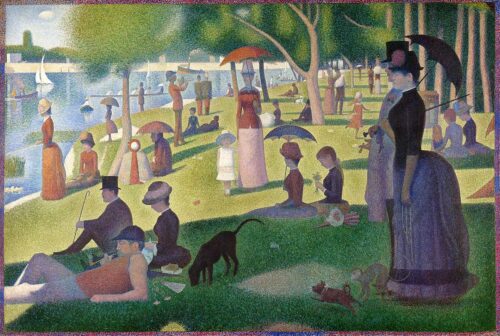

The musical is about two-and-a-half hours with two acts. The first act is about Georges Seurat and his meticulous creation of the famous and familiar pointillist painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jette. This took the real artist two years to make and around 60 different studies and sketches. We see how his obsession with his creation damages his relationships while also enjoying large comic scenes with the ensemble who together make up the figures in the final painting. The second act is about his fictional descendent and his own artistic career in 1984, struggling with some of the same issues as his ancestor. The play muses on the nature of the creation of art, the art world, authenticity, and community with others.

I saw their April 11th show with a highly engaged crowd. While the Nashville Rep always has great musicians (thank you Music City), this group was strikingly good. Taking on the demanding music, the orchestra was fantastic, playing nonstop and fluidly under Stephen Kummer’s direction. With the full orchestration of the original score we were able to enjoy the musical in its complete glory. All the textures and uniquely chosen timbres were perfectly balanced with the voices of the singers in Polk Hall, showcasing the skill of the Rep and the aptness of the space for musicals.

The singing was excellent, the cast completed their roles with vocal skill and tight ensemble collaboration. The accomplished Broadway performer Christine Dwyer was stunning as Dot, George’s mistress and eventually mother of his child, immediately winning us over in the opening number “Sunday in the Park with George.” Not only her voice, but her acting and knack for comedy were excellent. David Shannon, experienced in London’s West End, showed the complexities of George through his talented performance.

This opening number also holds a challenge: for most of the song Dot is complaining about modeling on a hot day until a new musical theme is introduced and she sings her intimate thoughts about George and herself, before returning to her complaining. The original show doesn’t only express through the music, but has her literally step out of her dress for the moment of intimacy. The “iron dress” remains standing in the rigid pose and she returns to it when she resumes her complaints about posing. It’s an unexpected and deeply funny expression of costume design meeting the music. The 2017 Broadway revival production dropped this element, having Dot instead step away from an upright parasol and remove her jacket. While this communicates much the same thing and is easy to accomplish, the Nashville Rep didn’t go the easy road. Costume Designer Melissa K. Durmon took on the challenge and provided the iron dress to audience delight. Since the various members of the ensemble comprise different figures in the final painting, most of the costumes were determined in 1886, but Durmon did a marvelous job of providing the details and fitting them perfectly to the cast.

As a musical about a man’s obsession with the creation of a painting, it’s rather important to be able to see the painting. The visuals of this show were excellent: a neutral-colored backdrop became a projector screen to showcase Seurat’s painting. For the first act the background was a projected image of one of Seurat’s many studies for the painting. It’s colorful and beautiful and of the actual location. Gary C. Hoff’s design was perfect! Characters often find themselves exactly where they will be in the final painting. The hugeness of the backdrop made it so that everyone in the audience had the perfect sightline to see their placement.

There are a few moments in the first act when we see George in his studio, and large picture frames with transparent screens are lowered. Images of the paintings he’s working on are projected onto these, literally allowing us to see George through his art. A great visual gag at the beginning of the play calls for the removal of a tree George dislikes while sketching, and the prop is lifted from the stage up out of sight.

The second act, where George’s great-great-grandson’s own art is a “Chromolume” was somewhat less impressive than the original production’s machine and light-show, but I think that has to do with the more dated nature of laser art. Born in the 90’s, I grew up with laser tag and the iTunes visualizer, so lasers feel commercial and corporate rather than imaginative or artistic. This production projected colorized words across the set, which was fine enough.

Such a thought-through musical as Sunday in the Park with George, with its music showcasing pointillism, its contemplation of the act of creation and the art scene, its hilarious interactions between the individuals in the painting, calls for concinnity in its performance. The message of this musical requires complete excellence to be communicated and the Nashville Rep did this.

The director of the show was Jason Spelbring, (who recently replaced the great Denice Hicks as Artistic Director of the Nashville Shakespeare Festival), and in his director’s note he wrote, “In this production, I want to emphasize the delicate balance between the work of art and the artist’s personal journey. The visual and emotional worlds of Seurat’s painting and his real life must be seamlessly woven together.” In this production they were. What a way to end the season!

While the Nashville Rep’s season is now over, you can find out more about their upcoming 2025/26 season here.

Broadway at TPAC

Kimberly Akimbo

The premise to this show is both common and strange. Kimberly is a 16 year old dealing with her dysfunctional family, teenage aspirations, and high school. What is strange is that she looks like a 60 year old woman due to a rare genetic disease. While a vague and fictional illness, it’s loosely based on progeria. This show somehow has strong morals and a powerful message while having me completely onboard with comic underage felonies.

The show is set in 1999, as the playbill says, “Before kids had cell phones.” This is an excellent choice, not only sticking with the setting of the original play, but avoiding the often cringy and dated attempts at hipness that other Broadway plays have recently made (like flossing in Mrs. Doubtfire and Wendy needlessly recording a TikTok in Peter Pan). Carolee Carmello does a great job of playing a teenager despite her real life age of 62. Her motions and manner of speaking feel like those of a teenage girl without any forced girlishness. Her voice is heavy with vibrato, unlike the other singers, adding to the difference. The other cast members playing her teenage friends are excellently cast. I think they’re actually teenagers, or if not, so close you can’t tell the difference. This is especially important in this show because you need Kimberly to stand out as an elderly-looking woman hanging with teens.

The show begins at the skating rink. We’re introduced to Seth, Kimberly’s love interest, and four other teenagers who not only have conflicting crushes on each other (forget love triangle, I’m not even sure what shape this one makes), but who are focused on their show choir studies. Kimberly interacts shyly with them. Then after a simple but satisfying downpour of snow her dad Buddy picks her up over two hours late because he’d been out drinking. At home is her narcissist mother singing my favorite song from the show “Hello, Darling,” which is her recording a video to the baby she is pregnant with.

The music to the show is solid. David Lindsay-Abaire’s lyrics are so good, and the music is fun and really grew on me. When I listened to the broadway cast recording after seeing the show I appreciated the music much more, despite the album’s sloppy overuse of pitch correction. Many of the songs are hilarious and perfectly matched to the on-stage action. The choreography to the show is often quite simple: singing to a camera while sitting on a couch, standing and facing the audience while singing a ballad. But there are other times where it’s surprising: the moment when characters who have been walking around on stage in ice skates go onto the ice and are suddenly skating around the stage (this bit of magic is done with liquid glycerin). “Happy for Her” is sung by Buddy while he’s driving Kimberly and Seth to school, and each move of the steering wheel results in realistic sways and bumps from the characters, getting sillier and sillier the more wildly Buddy drives. Simple slapstick is used when the group of teens tries to wash checks with Aunt Debra.

The pacing of the show is great. Two acts with one intermission, the first act introduces all the characters and their conflicts, and instead of leaving the second act to the denouement, the primary conflicts take place here. Kimberly’s criminal aunt Debra has followed them to their new home and takes over their basement, then convinces Kimberly and the other teens to join her in using a stolen mailbox for check fraud.

An aspect of the writing that is particularly good is the casual hurts that Kimberly experiences from everyone, their heedless remarks that remind her of her age or mortality. Except for her parents and Aunt Debra, no one is cruel or unkind; they’re just thoughtless teenagers. And Kimberly shows her hurt but doesn’t wallow in it, showcasing inner resilience and strength that not only is miraculous given her parents, but is the reaction that we’d all like to think we’d have in the same situation. Her love interest Seth also lets these casual comments slip, but we still like him. He shares an unhappy home life and a familiarity with tragedy, yet doesn’t let that control his life. His passion is for anagrams, which gives us the title of the musical: Kimberly Lovaco can be rearranged to say Cleverly Akimbo. Akimbo is to have a hand on the hip with the elbow turned out, or for another limb to be in a bent position. Merriam Webster clarifies that the term, while originally neutral, now implies defiance and confidence. Anagrams are the metaphor for the show in that you can take what you’ve been given and make something new with it. This is what Seth teaches Kimberly, and so we root for them because their relationship is more than just “he’s cute she’s cute.” Miguel Gil plays Seth with great musicality, charm, and enthusiasm.

The show isn’t just about nice teens being friends: Kimberly’s parents struggle and cause trouble for her, and her criminal aunt tries to involve the teens in an illegal enterprise. All three of these adults are delightfully and comedically horrible in their own ways, while remaining relatable in some aspects of their humanity.

The main struggle and message of the show are about mortality and living life now. In a scene where all the teenagers are sitting and talking, one of them says that right now isn’t real life, they’re just in purgatory for their future real lives. Each talks about what they’ll do in the future. Then they all look at Kimberly. She is silent: most with her condition don’t make it past sixteen, and she just celebrated that birthday. Unlike them, she’s stuck in the now because there is no future. In the touching song “Now,” they communicate how unreliable the future is, how they can hope to do things but keep in mind that tomorrow might never arrive.

We all face death, imminent or decades from now, we just don’t know. This show reminds us to face that death and allow the knowledge to prompt us to live life in the now. Like many old adages this sounds dully moralizing, but like all good fiction, this play brings this truth to life.

The end of the show doesn’t fix all the problems faced in the story, there’s no miracle cure or sudden reform of a parent. But it is uplifting and happy and brave, and the whole story’s sincerity ends sincerely. There’s some play logic: I’m totally in support of some federal felonies, and I’m able to laugh at the actually horrible parents and aunts and their activities. But the meaning is only helped by laughter.

Kimberly Akimbo is at TPAC through April 13. For more information, see Kimberly Akimbo | Tennessee Performing Arts Center and Kimberly Akimbo.