The MCR Interview:

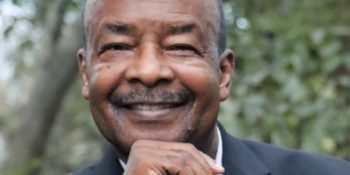

The African Company Presents Richard III: Interview with Director Lawrence James

Dr Lawrence James is directing a staged reading of The African Company Presents Richard III with the Nashville Shakespeare Festival at the Darkhorse Theatre February 22-24. This is a slightly edited transcription of his phone conversation with Grace Krenz on February 15, 2024.

Grace Krenz: When I first saw on the Nashville Shakespeare Festival website, The African Company Presents Richard III, I got very confused despite its clear title, because I was like, “is this the Nashville Shakespeare Festival or is it the African Company, which is in Nashville, presenting Richard III? Then I googled it and was like, “oh, it’s a play by Carlyle Brown and it sounds absolutely fascinating.” So, could you talk us through a little bit of the history?

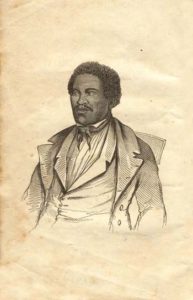

LJ: Yeah, it is a fascinating story and I’m just so glad that Carlyle Brown tried to bring it to life in some way. The history of the play itself is that it concerns a true incident in New York City in 1821, where a troupe of free African American actors mounted a production of Shakespeare’s Richard III, and the play did attain critical and financial success. But then a larger white company, the well-established Park Theatre, during that time, connives to shut the production of the African Company down, to prevent competition with its own production of Richard III at the same time. And so the play focuses in on the company of African American actors. They go through their typical rehearsals and look at the reviews, and war about their roles, and how successful they are, and their costumes and all the other things that all actors go through. And at the same time they fill in a lot of their own background details, of their own special circumstances. For example, most of them work and they have other jobs, particularly the ladies, who work as domestics and so they talk about their servitude and a couple of the major characters are from the West Indies. And so the play does go back in time through memory in some moments there, and back to the present. You have some element of attempts at romance, but it really focuses in on their lives as actors, as African Americans, in 1821 America, and the dissonance and the happy times too: the positives of being free African Americans, but having to try to put on a show and to compete, of course, with a much more established white company and some of the famous actors that they’re bringing in from Europe and whatnot. So it is history, but it’s also character study, personalities of Blacks during this time.

GK: Wow, that sounds fascinating. Was the African Company a newer theater when they started to put on Richard III? Had they been established for a while?

LJ: Yes they had, the company had been founded by William Brown. He was a free African American coming from the West Indies. The company would put on plays regularly and they had a very good following of Blacks in New York during that time. In fact, Brown used his own home and the plays would be done in his backyard, particularly on Sunday evenings, and so you have a lot of the Blacks coming in as a Sunday outing. People would be in their Sunday finery, and so in addition to maybe going out to get some ice cream or something like that they would go and gather in Brown’s backyard and see these plays. So yes, they had done a number of shows.

GK: And so when they were presenting Richard III and being successful at that, were they still doing it in his yard, had they rented a theater or some other location?

LJ: Well, this is where it gets to be interesting. Yes, they would rent a theater, and they were going bigger now. They were being more expensive. So they’d started in the backyard, and then they went and they would begin to rent space. And here in the play, where the conflict gets real, they rent a ballroom in a hotel right next to the Park Theatre, where the other Richard III was being presented. And so you have quite a conflict here with the managers, Brown being the manager of the African Grove Company, and Richard Sheraton being the manager of the Park Theatre, and the police get involved, so it has some interesting twists and an ending to it.

GK: It’s kind of meta in a Shakespearean way of having the play within the play. I find it funny if the villain is gonna be the leader of the white theater, his name is Richard and the villain of Richard III is Richard. That’s just very tidy, I like that.

LJ: [Laughs] Yes, that’s right.

GK: Now was this the first Shakespeare play that the African Company did, or was this one of many?

LJ: This was one of the first Shakespeare plays that they had done. They had done some other original things there, and then near the end of the play we find out that Brown becomes motivated to write some more plays. So no, this was not their first play, but it was one of their first Shakespearean productions that they did.

GK: So these two competing theaters are trying to, instead of doing a dance-off, do an act-off. Was there a big disparity between the manner of their presentation, or the sort of costumes or attitudes going into it?

LJ: Well, in regards to the black actors, that’s a part of the story. One of the themes, or the subplots here, and I’ll kinda jump forward and say, [Carlyle] Brown introduces his play with the poem “We Wear the Mask” by Paul Laurence Dunbar. And in that poem the persona says, “We wear the mask that grins and lies, It hides our cheeks…” Then it goes on, “And why should the world be overwise? We grin and we smile but oh what all we have to bear,” and then it ends with “we wear the mask.” So the play is not that specifically about performing Richard III, even though there are some monologues and some scenes. It’s more about the characters and their joy, for some, in performing, but the dissonance and the conflict that others have in, you know, I have to say “yes sir” and “yes ma’am” and bow and do my servitude and clean the house and cook and do all of these things, and then I come and I play Lady Anne or I play a King Richard, or this other person who I’m not able to “be” or show to the real world. And so that’s really the story. Once again, there are a few scenes and monologues from Shakespeare’s play, but the story is really the company’s story: who they see themselves as, and where they came from, and what they do with their jobs and their relationship with the majority-white world, how they play that. And then, coming to try to be an artist and perform a great piece of art, but how is the character in Richard III different from the character in real life? And that is really the story.

GK: Dang, that is really interesting. I feel like this play seems to be covering one of those gaps in our education or historical understanding. I feel like at least, growing up, I never heard about the plight of African Americans living in New York City forty years prior to the Civil War. So I don’t have a good understanding of what their legal status would be like in the city. “Free,” but unable to vote. But how does that come across if you’re a tenant, or you’re trying to rent a ballroom? Did they come across some of the difficulties of what later would be segregation in the South, or were they more free at that time?

LJ: You know, that’s a great question. From the play itself we don’t get a lot about the kinds of experiences they may have as far as going about everyday life. Some of the characters do relay about some of the white people that they work for, and what that experience is like. And so there’s some positives, but they also talk about the negatives of that. It does relate some of the problems of being out in groups and maybe some of the harassment that comes about by the police if you’ve got too many Blacks during this time gathering. And oh, especially, of course, when you have the Blacks that do protest the Park Theatre, and that’s a serious conflict that comes about. But other than that, as far as being able to rent the ballroom next door to the Park Theatre, as one of the characters says, “As long as we’ve got some green,” some money, they will rent it to you. So only in the instances where there’s a gathering and particularly, when the Blacks are protesting, do we get a feel of the law of the police coming down on them. But other than that, we are told about their everyday life working, about the Sundays when they’re free and they’re able to dress up and go promenading out to the park and whatnot. So there’s kind of a balance between the negatives of being Black in New York during this time. And of course they were “free” Blacks, but of course there were some problems that were experienced there. But no, I think the play kind of balances it out with the positives and some of the negatives.

GK: So I looked up this play and saw it was first published in 1994. How did you first come across it?

LJ: I was familiar with the play and with the story. You know, it’s such a great and intriguing title, as you say, we look at The African Company Presents Richard III, so I was familiar with the script, but it really came into focus by way of Denice Hicks and the Nashville Shakespeare Festival. Denice has served on our theater advisory board for a number of years, and that was one of the ideas that she had brought some time ago, several years ago. She was interested in talking about it, “you know, this is such a great script, I’d love for us to think about doing it.” So it came about this past year, well maybe two years ago, that we really sat down and we talked about it. In fact, there was supposed to be an actual staged performance of this play, this month, at this time, here on the campus of TSU, as a collaboration between our theater program and university, and Nashville Shakespeare Festival. However, it fell through at the last minute, and was primarily by way of TSU. Nashville Shakespeare did an awesome job of stepping forward, really wanting to do something for the community, for the university, for the students, as well as for them, because they do do those kinds of things with other universities as well. So that was actually scheduled during this time slot here, but as I said, that fell through, and so Nashville Shakes decided to at least go with a staged reading of the play, off-campus, without any ties to TSU.

GK: Would you describe the difference between doing a staged reading and a full-fledged performance?

LJ: Sure. Well, you know, staged productions rely on a very inextricable relationship or balance of dialogue, conversation, character, interplay, paired with physical action, character business, to tell the story. The staged reading has very limited movement and there’s a variety of styles of staged reading, where you have the cast sit with the folders or the script and just read, other variations maybe you have the cast reading with reading stands or reading and up and doing actions. So there’s a lot of different variations with that, but the focus is more on the reading and creating the action through the dialogue of the characters with limited physical movement. Whereas of course, in the staged production, action and business of the characters tell the story in conjunction with the dialogue and the words of the script.

GK: For your performance, not to ask you to give spoilers or anything, but what sort of style of staged reading will you go with?

LJ: We’ll see what we’ll do with the script and with reading stands and whatnot. We’re exploring the space and the stage so I’m finalizing some thoughts. I’m thinking that we’re probably going to be using scripts with movement. It will still be a reading: acting and performance with some movement to tell the story, but we won’t be just sitting, reading, the entire script. No, there will be some movement, blocking, action, along with the actors using the script as they play the characters.

GK: As an artistic director, how is directing a staged reading compared to directing a fully staged performance?

LJ: Of course they are similar in ultimately being able to tell the story, bring the script to life, actualizing it in performance: well what did Shakespeare intend in Richard III, what does Brown intend in the African Company Presents? A major difference is getting the audience to visualize in the staged reading. That is, getting the audience to see the action of the play primarily through hearing, with some movement as opposed to seeing live action. So there’s more emphasis, I think, on the language, on the imagery, and the actors being able to color those images vocally. So that implies a lot of vocal agility, vocal expression, facial expression, without taking the play completely out of the mind of the audience. So it’s that balance of language, the creation of language, imagery, action, without losing the story, because the actors do have the script in hand, and so, you know, how literal are you? How much movement there? So it’s a balancing act. Vocal, life, with some suggestions of movement, to get the audience to see the action in their minds. And some of it visually too, to a limited degree.

GK: Well excellent. Now I think that I went through all the questions I had, but do you have any question that you think I should have asked and that you have a good answer for?

LJ: [Laughs] No not really, I’ve enjoyed talking with you. I’m appreciative of you doing this, we’re looking forward to it. But yes, I think that there’s a lot to be learned in this show; it’s history, it is life, it is the past but it also is the present as well. And I think that those who come and see will be glad that they did. And who knows, in the future maybe we’ll get an opportunity to actually do a staged production of the play. That would be wonderful.

GK: That would be fantastic. I’m looking forward to seeing the show! Thank you for speaking with me and taking time out of your day!

LJ: Thank you!

Tina Turner – The Tina Turner Musical

Tina – The Tina Turner Musical is a biographical jukebox musical, covering her life from her childhood to her fifties, ending at her record-breaking performance in Rio De Janeiro in front of 180,000 fans. Tina’s life was not easy. The musical starts in her childhood. She is born Anna-Mae in Nutbush, Tennessee, and after her mother leaves her violent father, she is abandoned by both to live with her grandmother until her late teens when she moves to St. Louis to live with her mother and sister. After she sings powerfully when offered the mic at a show, she gets the attention of Ike Turner, who has written the hit song “Rocket 88.” He brings her into his band and quickly dominates her. He ends a seemingly healthy relationship with another member of the band, changes the name of the band to the Ike and Tina Turner Revue, making her take on the stage name of Tina Turner, and finally convinces her to marry him. He is openly unfaithful, addicted to drugs, and beats her and her two sons. She finally, at the end of the first act, breaks out of the terrible marriage to freedom and safety. The second act shows her struggling to get by after the financial hits of divorce, losing her band with Ike, and lawsuits, then her development, with the help of her manager Roger Davies, into her new sound, hair, and solo success.

This adaptation of her life to a two-act musical keeps things simple; except for a brief moment at the beginning when we see mature Tina preparing to go onstage, events occur chronologically, avoiding the confusing pitfalls of artificial frame stories and the lurching momentum of flashbacks. I appreciated this clarity of the story’s presentation. Its pacing never slowed, but sometimes I wish it did; we never got to see Tina in repose, at her ease with family or friends. Her every moment is action or plot; the show communicates the events of her young life more than it does who she is. After seeing the show, I can tell you that Tina Turner became a strong woman who achieved great success despite overwhelming difficulties of abuse, racism, and starting her career over, that she’s worthy of respect and her music is lasting– but I can’t tell you what sort of personality she had, what made her laugh, what she for fun, or how she was as a mother or friend. I also wish that we had gotten to see more of her being happy in her success, and more of her relationship with Erwin Bach, the German music executive who became her second husband, and who was with her for almost 40 years, until her death in 2023. While we see much of Ike, we saw little of Bach, who even gave her one of his kidneys when she was seriously ill in 2017. Tina Turner did write multiple memoirs, and there’s a biographical film from the 90’s, so perhaps the creators of this musical didn’t intend to cover every aspect of her story.

The musical is full of Tina Turner’s iconic hits, some diegetic and some not. I preferred the diegetic songs, when we got to see the costumes and dancing, the energetic stage presence of Tina Turner performed by the lively Zurin Villanueva. The songs are not placed chronologically, so characters sing 80’s ballads in the 1960’s, undercutting the contrast of her reinvention. Some of the song lyrics feel slightly out of context, and in one scene, after Ike brutally hits both his wife and son, he sings “Be Tender With Me Baby.” I was unfamiliar with the song, but I felt that if I had been more familiar with her music, I would have been irked that a touching song was now warped in the mouth of a violent manipulator. Before seeing the show, I anticipated seeing “Proud Mary” performed, but I was disappointed to have them break the song off shortly after getting to the fantastic, fast portion, for backstage domestic violence. At the end of the show, after the bows, they perform a medley which includes “Proud Mary,” but only the ending portion of it, and it doesn’t hit the same way when its slow-grooved beginning hasn’t set it up.

The costumes are a lot of fun; we get to see decades of American fashion as well as many different stage costumes, including a vibrantly tacky Las Vegas performance. The orchestra is excellent and comes on stage at the end, allowing the audience to see the musicians perform some impressive instrumental solos. The set design is minimal, restricted to a few small pieces and props to set scenes and relying heavily on a busy screen which works as the backdrop. This screen is less visually appealing than classic backdrops (especially since many of the backgrounds it shows are deliberately out of focus) and is frequently distracting, moving swirls or sparkles or abstract effects accompany many scenes, as if the audience could get bored by Broadway performers would be captivated by glorified screensavers.

Opening night at TPAC, the hall was packed and the audience was invested, angry murmurings following Ike’s abusive actions, and cheering following a hospital scene where Tina stands up to her mother and Ike’s attempt at manipulation. At the end, as Tina and the ensemble performed their high-energy medley, people stood and the crowd screamed like they were actually at one of her concerts.

The cast was good. Zurin Villaneuva plays Tina Turner with unstinting energy and a wide vocal range, Deon Releford-Lee as Ike has a smooth manner which changes quickly to vicious anger.

I am very impressed by Brianna Cameron, who plays young Anna-Mae; that 4th grade girl has a bigger voice than most adult women, and her range is equaled by her vocal control.

This musical is for the fans of Tina Turner who want a little bit of everything, and to see a glimpse of what it would be like to see her perform live in concert; this Broadway cast does it better than a cover band ever could.

Tina – The Tina Turner Musical is at TPAC through February 18, 2024. For tickets and more information, see The Tina Turner Musical | Broadway in Nashville at TPAC.

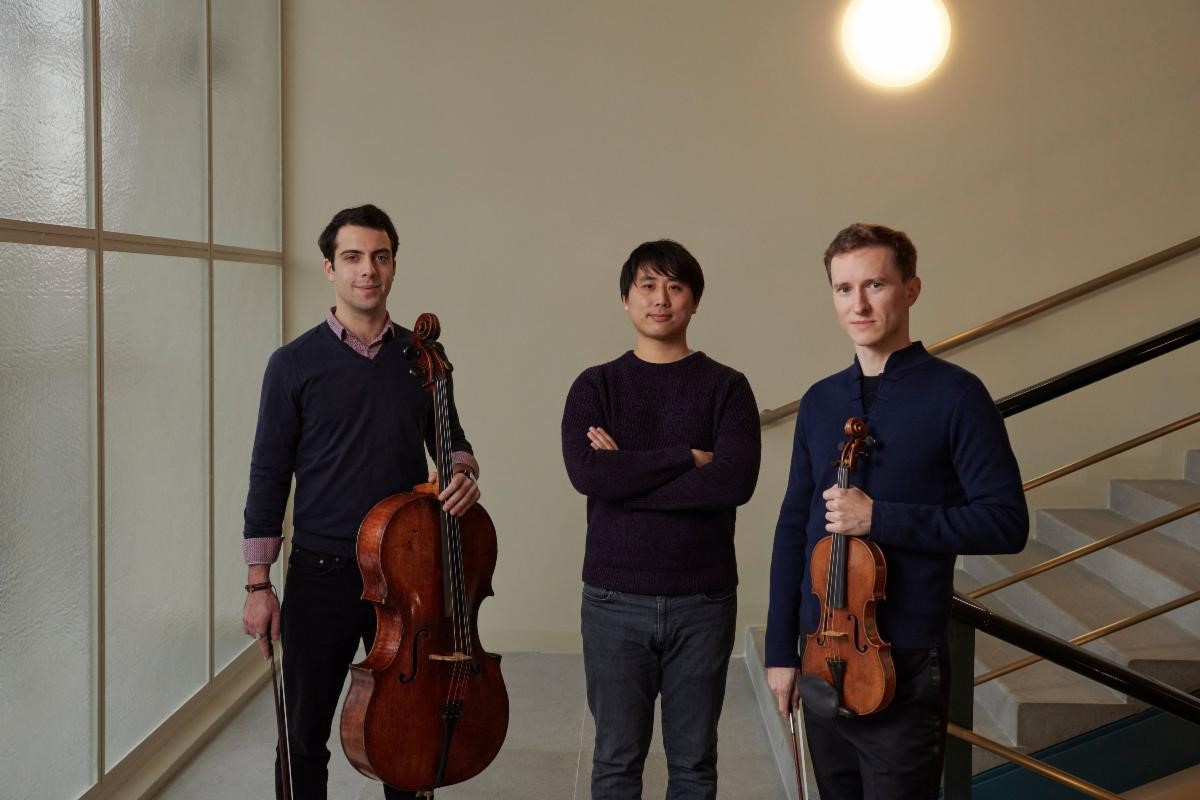

Prokofiev, Shostakovich, & the Nashville Chamber Music Society at the Steinway Gallery

There’s something particularly compelling about Prokofiev’s F Minor Violin Sonata, Op. 80. It’s got this devastation and gloom about it that are impossible to miss and harder to shake. Program notes, virtually as a rule, save themselves a lot of ink by refraining from flowery, fruitless attempts to get at this aura in prose. Instead, they just quote Prokofiev himself, who apparently described at least some sections of the piece as “wind passing through a graveyard.” (If anyone out there knows the actual source for this statement, I’d love to know what it is!) But it’s not just that the sonata’s mood is so powerfully or uniquely dour—with maybe the exception of a few all-too transient moments in the energetic last movement, Prokofiev never lets up on the misery for long. It’s astounding the range of foul moods he finds across these four movements, where even a sudden (brief) turn to the tonal and tuneful in the second movement (marked eroico) feels more like seasickness than relief.

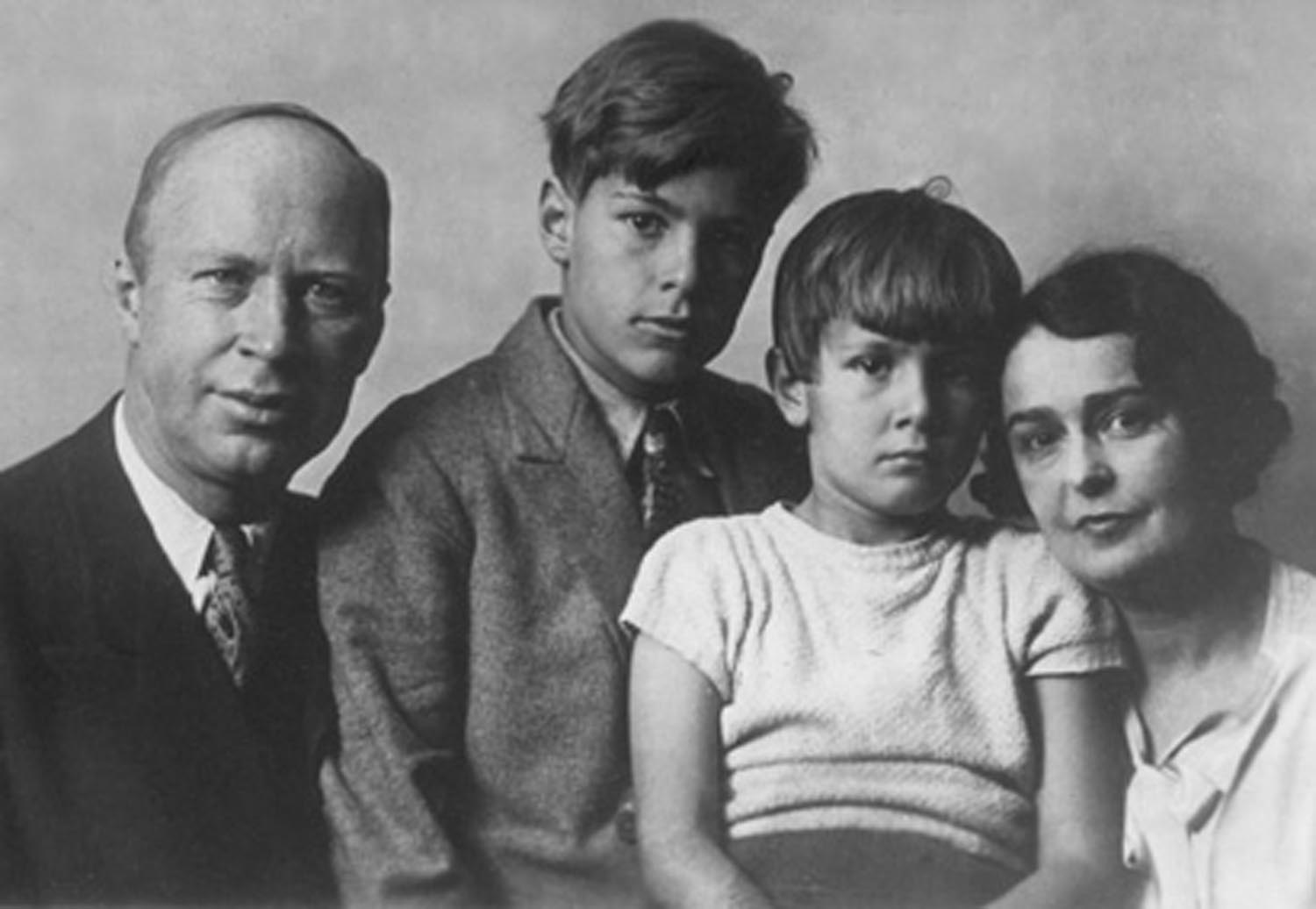

Prokofiev started work on the piece in 1938, but it didn’t see a premiere until 1946. Unlike a number of the composer’s other works, for instance his first violin concerto, which sat completed but unperformed for five years, the premiere of Opus 80 happened uncharacteristically quickly after its completion. That the piece instead remained incomplete for so many years first (and for these specific years) often adds an extra, crucial layer of mystique to the piece’s appeal. Without some clear paper trail of any number of more boring reasons for Prokofiev putting the sonata down for those years to get in the way, it’s even easier to let the relentless misery at this piece’s core truly balloon into something larger than life.

Since Prokofiev didn’t work on the piece at all during the years of the Second World War, and since it was during these years that he began to experience most directly the turbulence of Soviet political life, having moved back to the Soviet Union permanently in 1936, a political reading of the work, or at least interpreting the piece as a reflection of the dire political times themselves, is common and probably not far off the mark. Though it’s not like Prokofiev’s personal life during this same period was any less a source of misery. His marriage to the Spanish singer Lina Codina was beginning to unravel, largely as a result of the affair Prokofiev was carrying out with a woman, Mira Mendelson, who was half his age when they met in 1938. The affair carried on for years, and though Prokofiev and Lina had finally separated by 1942, they were technically married until the beginning of 1948. (Rather than being granted a divorce, their marriage was ruled invalid and therefore nullified.)

And of course, it’s not like there was ever a clear delineation between the political and personal for Prokofiev. Lina had never been a proponent of their moving to the Soviet Union, in part because of the censorship and legal troubles faced by Dmitri Shostakovich in the years just before 1936. After then having her travel visa revoked in 1938, she made several attempts to get a visa instead to leave the Soviet Union altogether, all of which were rejected. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Soviet authorities viewed Lina, a foreigner with a history of expressing political discontent, with some degree of suspicion. Very shortly after she and Prokofiev were legally separated, Lina was arrested and spent 8 years imprisoned, never seeing or speaking to her ex-husband again.

In any case, whatever the “source” of the darkness of the Violin Sonata in F Minor might have been for Prokofiev or any of his biographers, it might just as well have been the cold and gloomy rain coming down outside the Steinway Gallery last month the night of the Nashville Chamber Music Society concert. The recital hall at the back of the gallery is small but elegant, and a perfect size for their regular crowd. An intimate venue like this also helps conversations cross-populate in the audience before the performance and during the intermission, which is a special element of NCMS concerts, and one that speaks to their small-scale, personable origins as Wednesday night concerts at the Frothy Monkey.

The friendly nature and humble origins of the NCMS belie the top-notch nature of their ever-changing lineup of performers—here featuring Blair School of Music faculty members on violin and Heather Conner on piano, and the founder of NCMS MaryGrace Waggoner on cello.

The program included not just Prokofiev’s Violin Sonata in F Minor, but also his Sonata in D Major, Op. 94a, originally written as a flute sonata, but then later adapted into the Violin Sonata No. 2 (which was confusingly first performed in 1944, two years before Sonata No. 1), as well as a very early work by Shostakovich, his Piano Trio No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 8. The piano trio and Prokofiev’s Sonata in D Major were perfect foils to the F Minor sonata, especially the bubbly, up-tempo Opus 94a. The scale of the piano trio is a bit less ambitious than the violin sonatas (especially the F Minor), but it’s astounding to hear how the grand, romantic final moments squeeze out of three instruments almost an entire orchestra’s worth.

The placement of the Shostakovich second in the program, and directly after the F Minor sonata felt like a somewhat unusual choice. Not only would the shorter, and let’s say friendlier, piano trio have served as a better program opener; the vague sense of disquiet the Prokofiev leaves you with needs the kind of space a twenty-minute intermission can give. Oh well, like I said, the atmosphere at an NCMS concert is too friendly to leave everyone brooding and serious like that, and maybe it’s best not to dwell there too long after all.

Tina: The Tina Turner Musical Coming to Nashville

Tina–The Tina Turner Musical is the inspiring journey of a woman who broke barriers and became the Queen of Rock n’ Roll. One of the world’s best-selling artists of all time, Tina Turner has won 12 Grammy Awards® and her live shows have been seen by millions, with more concert tickets sold than any other solo performer in music history. This musical depicts her life and career as she must fight to transcend racism, misogyny, and abusive relationships to achieve lasting love and success. Featuring her much loved songs, Tina–The Tina Turner Musical is written by Pulitzer Prize®-winning playwright Katori Hall and directed by the internationally acclaimed Phyllida Lloyd.

Recommended for ages 14+. The production includes scenes depicting domestic violence, racist language, loud music, strobe lighting, haze, and gun shots. Please note that Tina Turner does not appear in this production.

At TPAC’s Andrew Jackson Hall February 13-18, for tickets and more information: The Tina Turner Musical | Broadway in Nashville at TPAC