At the Schermerhorn

Shostakovich Framed by Beethoven!

On April 5 & 6 the Nashville Symphony presented Beethoven and Shostakovich, a rather odd concert that framed Dmitri Shostakovich’s first Cello Concerto, played by Zuill Bailey, with Ludwig van Beethoven’s symphonies No. 8 and No. 4. The selection of these pieces is “odd” because they are literally even, namely choosing exclusively even-numbered Beethoven symphonies, a set that have long been recognized as being lighter, backward looking (as is the case with number 8) and with an emphasis on charm that is overshadowed by the gravitas of their odd counterparts. However, against the immense grandeur of the fierce Russian concerto, written in 1959 by Shostakovich for his friend, the virtuoso Mstislav Rostropovich, Beethoven’s symphonies provided a balanced, dare I say “classical” contrast that made for a rather enchanting evening.

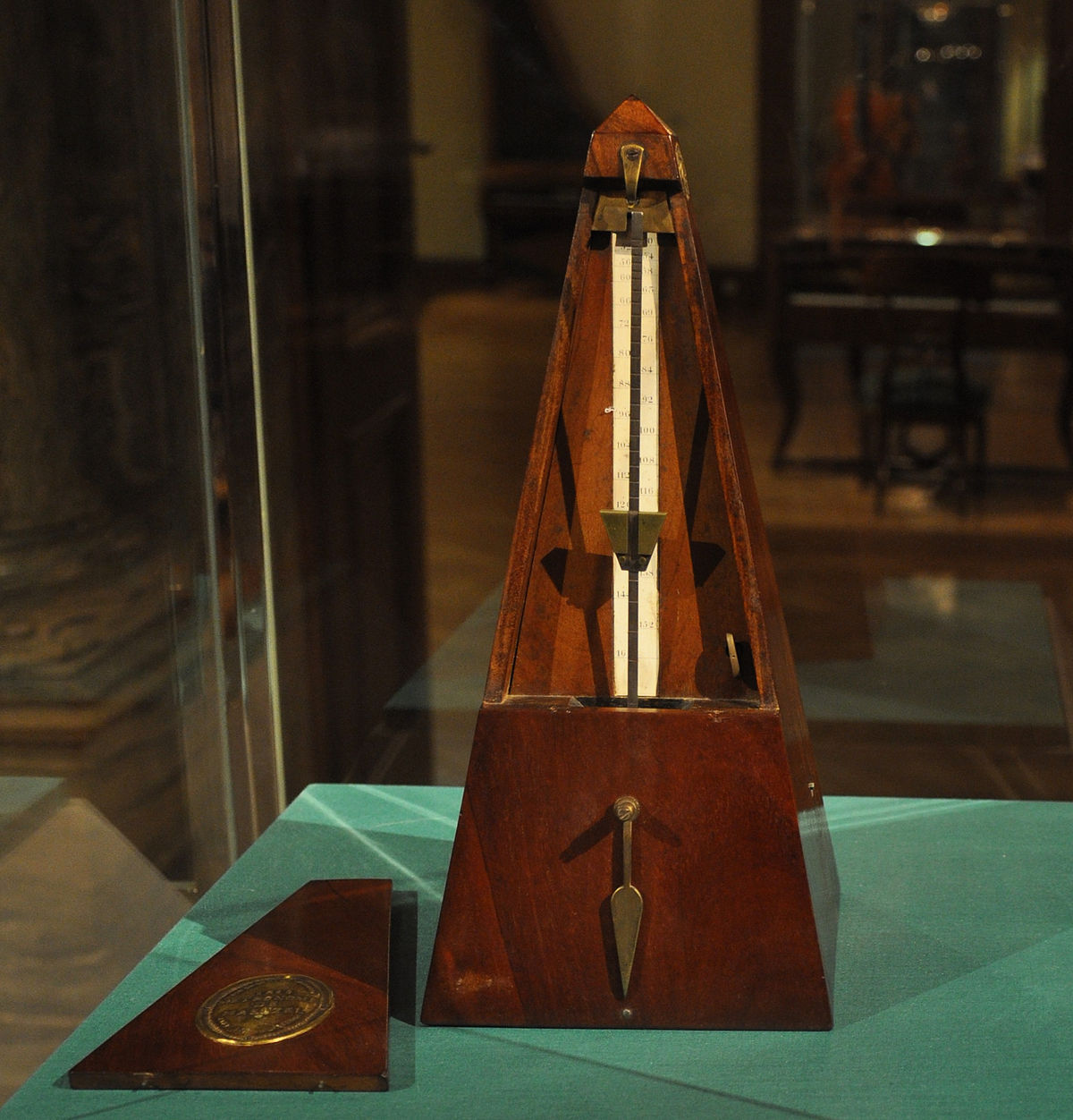

The concert opened with Beethoven’s 8th, a concise essay composed without introduction or slow movement. Instead of a slow introduction, the movement is marked by a “tick-tock”, marked with a wonderful optimism by the Nashville woodwinds that reminds the listener that Beethoven had just become acquainted with Johann Nepomuk Mälzel and his “chronometer” (metronome). (Musicologists have since determined that the story of the relationship between the movement and the metronome is probably bunk, but if tradition inspires it, who listens to musicologists anyway?). Nashville’s horns in the middle of the third movement “Menuetto” allowed themselves to stand out in a proper, classically-minded, Beethovenian manner. In all it was a delightful performance.

Similarly, after intermission, Beethoven’s 4th Symphony was performed in a delightful manner. Again, especially the woodwinds, with the dialogue between the oboe, flute and bassoon that makes up the second theme of the first movement. The final movement, with its perpetuum mobile, allowed the strings to shine too, and that they did. It is worth noting that, while we hear this work as convention, Carl Maria von Weber decried its innovation: “…and to end all a furious finale, in which the only requisite is that there should be no ideas for the hearer to make out, but plenty of transitions from one key to another – on to the new note at once! never mind modulating – above all things, throw rules to the winds, for they only hamper a genius.”

Between these two very nice pieces, Shostakovich’s Concerto was sublime. The opening seed of the movement, a spry four pitches in solo cello (related to his personal four-note motto and which appears in several other of his works) opens the piece with what seems to be sardonic verve. The motto unified the work’s movements in its reappearances even as it is subjected to an incredible range of thematic transformation. One could feel the orchestra hit their stride in this opening movement. When it came time for the giant cadenza (a movement unto itself) Bailey earned his pay. The lyrical moments ran just as intensely as the movement’s later technical fireworks. After several rounds of applause, Bailey came back out and gave us a beautiful encore of Gluck’s Dance of the Blessed Spirits.

Looking back at this concert, I think Maestro Guerrero was right in his programming. Such intensity in composition and musicianship from Bailey and the Shostakovich required the frame of Beethoven’s utopian optimism. I’m used to Beethoven being the center of gravity, but it seems that he serves well as its foil too. The Nashville Symphony classical series returns on May 2-4 with Beethoven’s Violin Concerto and Richard Strauss’ An Alpine Symphony.