Rituals and a Serenade at the Schermerhorn

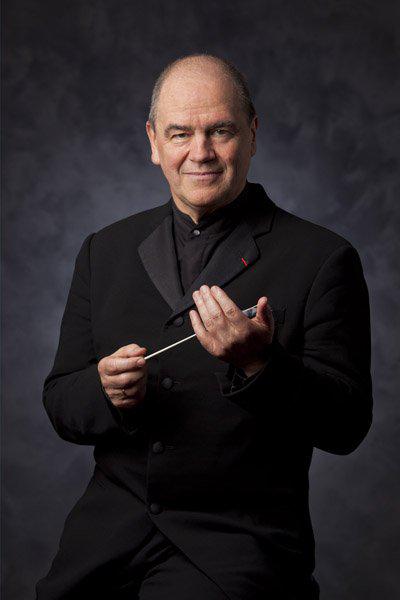

On November 16th and 17th the Nashville Symphony along with the Nashville Symphony Chorus, hosted visiting conductor Hans Graf for an interesting concert of late Romantic and Neo-classical works, including Richard Strauss’s Serenade in E-flat Major (Op. 7), Igor Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, and Maurice Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé at the Schermerhorn Symphony Hall.

Strauss composed his Serenade in E-flat Major, Op. 7 when he was just 17 years old, decades before his famous tone poems and his shocking operas Salome and Electra. As such, it reveals his adoption of the classical style, an attribute that will underpin his darker, late Romantic works. Titus Underwood, Nashville’s principle Oboist, deserves special mention for the subtle and beautiful handling of Strauss’s opening theme. It was an interesting piece for Maestro Graf to open the concert, but well chosen as the intimacy and utopian idealism would provide a powerful contrast with the works to follow.

If a conservative, Classical approach lied beneath Strauss’s Serenade, Stravinsky’s neo-Classical Symphony of Psalms places the era’s cold symmetry and objective expression in the forefront. Stripped of his Russian primitivism this late in his career, the Symphony of Psalms remains primal, but universal, expressing a ritual distinctly human yet without any grounding in ethnic reference. Taking verses from the Latin Vulgate bible, the lines aren’t set with an emphasis on the meaning, but instead their ritualistic sound. In this performance, Chorus Director Tucker Biddlecombe had prepared his singers quite well. The chant-like monotony of the first movement, much of it is given on two notes, was haunting yet revelatory. For Graf’s part, he maintained a strong balance among the various parts of Stravinsky’s odd orchestra, lacking as it does the emotional high strings and instead employing an enriched (and objective) wind section. The balance was particularly well done in the second movement with its multiple fugues and insistent imitative counterpoint.

The final, and longest piece on the program, Ravel’s ballet, Daphnis et Chloé, also begins with a lengthy ritual, this one more otherworldly and mystical—the story follows two foundlings in a pastoral landscape where they are confronted by nymphs, Shepherdesses, the God Pan and Pirates among other things on their way to true love. The plot provides ample opportunities for Ravel to demonstrate his extraordinary ability in orchestration. The clarinet and flute excerpts from this piece are legendary, and Érik Gratton (Principal Flute) and James Zimmermann (Principal Clarinet) handled them deftly. The sunrise in the final part, coupled with the beautiful wordless chorus closed the evening in a lovely way.

In all it was a very nice concert, if perhaps just a little short, and containing three pieces you don’t get to hear too terribly often. The Aegis Sciences Classical Concert Series continues in January with Cosmos – an HD Odyssey featuring the New World Symphony and the rarely heard Violin Concerto by Alban Berg, performed by Gil Shaham.

Grace and Grit: 72 Steps

Voting and ballet don’t appear to have much in common, other than they are acts performed by humans; but the Nashville Ballet has set out to challenge that idea. 72 Steps, a new ballet choreographed by Gina Patterson and performed by the Nashville Ballet’s second company, NB2, premiered last Saturday at Harpeth Hall’s Frances Bond Davis Theater to a packed house and riveted audience.

The new ballet depicts the struggles leading up to the passage of the 19th Amendment in the Tennessee House of Representatives, which made Tennessee the 36th state to give women the right to vote, and triggered national ratification. While this may sound like an odd topic for a ballet, it was an effective and moving medium to tell a story of perseverance, change, and upheaval. The title of the ballet, 72 Steps, is meant to both represent the number of stairs women had to climb to reach the Tennessee State Capitol building to hear the outcome of the vote by the House of Representatives, and the number of years women spent working towards suffrage.

Patterson’s choreography is modern and fluid, with dancers assuming rolls and blending back into the corps de ballet seamlessly. Some of the choreography was direct, telegraphing an emotion or intent, such as a male dancer pressing down on a female dancer’s head while she attempted to climb imaginary stairs, sinking lower and lower until she was lying on the floor. Another powerful movement set was a line of women dancers holding their hands over their own mouths; one by one the dancer to the right would pull the hands away from the dancer on the left, figuratively freeing her voice. The dancing itself was superb. All eight members of the cast were electrifying performers, and in the brief moments where lines were spoken each voice was clear and distinct.

The ballet was structured in loose vignettes; some scenes took place on the steps of the Capitol building, while others were in more intimate spaces. As far as a narrative, the two clear characters in the piece were Harry T. Burn, a young member of the Tennessee House of Representatives, and Febb Ensminger Burn, his mother. The two danced a beautiful and unconventional pas de deux toward the end of the ballet, with Febb lifting and pirouetting Harry in a way that flipped the gender stereotypes of the dance. This helped to illustrate the nurturing strength of Febb and Harry’s youth. Shortly thereafter, Harry read from a letter he received from his mother, in which she implored him to vote for suffrage.

One of the most striking aspects of the ballet was the costume design. Jocelyn Melenchincky designed simple shift-style dresses for the women, and frock coats for the men. The frock coats came to represent power, dominance, and anti-suffrage sentiment, and at various points in the choreography both male and female dancers whipped the coats on and off to create feelings of menace, conflict, or longing. The two pas de deux in the piece both featured men without their coats, transforming them into sensitive and vulnerable beings. Another important aspect of the costume design was a dress form on wheels, sporting a long starched white dress. At different points of the piece dancers- men and women both- would take turns sliding inside the dress form and walking soberly across the stage. According to Patterson in a Q&A afterwards, the dress on the dress form represented the history and tradition of conventional women’s roles, and the hope that these roles could adapt and move into the future without severing the connection to their past.

The score of 72 Steps was composed by Nashville composer Jordan Brooke Hamlin, who mentioned in her section of the Q&A that this was her first collaboration with dancers. While the expectation going in might have been for period music of the 1920’s, Hamlin opted (with great success) for a hybrid of acoustic and synthesized sounds which were at times hypnotic and tribal. The emotional core of her work centered on recurring cello solos, gorgeous lines that floated over a percussive background. Hamlin’s experience as a french horn player showed itself in her deft handling of a brass fanfare motif that appeared during moments of conflict or high excitement.

The League of Women Voters commissioned this work with the hope that it will be performed across the state in conjunction with the middle school history curriculum. This ballet will surely bring history alive for young students, as many of the issues addressed are ones we are still wrestling with today as a society. When a piece of art can educate, inspire, entertain, and open the door for discovery, it is the most vital kind of art. 72 Steps does all of the above, with grace and grit.

Nashville Opera’s the Three Decembers

On November 9-11 Nashville Opera offered a production of Jake Heggie’s nostalgic Three Decembers at the Noah Liff Opera Center. Composed as a commission by the Houston Grand Opera in 2008, this intimate chamber opera, based on an original play by Terrence McNally which was set into libretto by Gene Scheer, visits with a small family over the course of three decades (1986, 1996, 2006) as they “struggle to connect and make sense of long-kept secrets that are revealed.”

Heggie’s work deals with the issues of the day (AIDS, alienation, and social judgement) from within the context of the timeless narrative of a parent’s sense of responsibility and guilt set against the child’s search for independence and meaning from the events of their lives. The opera is built on three characters, a Broadway actress and single mother Madeline Mitchell (Emily Pulley, mezzo-soprano), her daughter Beatrice (Cree Carrico, soprano) and her son Charlie (Robert Wesley Mason, baritone).

Each of the three acts hinges on Madeline’s yearly and borderline narcissistic “Christmas Letter” in which she treats of the recent events in her life. Her apparent lack of compassion for Charlie’s significant other, who is suffering from AIDs, is the primary dramatic contrast which pushes the plot forward. Mason’s voice, a strong and bright instrument, well expressed his naïve and idealistic character’s overly sensitive reactions to his mother’s weak efforts at compassion.

His sister, whose story comes closer to the fore in the second act, was played very well by Carrico. Her character’s somewhat ambiguous alcoholism and its cause (we find out in the third act that her husband has been adulterous) is an ingenious move on the part of Scheer, revealing in an opera of secrets, that hiding the problem can be worse than the problem itself. Carrico sang beautifully with a fluent diction and an attractive tone that humanized her character’s quick shifts in mood and temperament. To the mood shifts Carrico’s acting was fantastic, portraying her character’s “triggering” moments (Beatrice is a 20th century Rosina) with a believable and beautiful authenticity.

In the third act, Pulley ruled the stage and story. She brought the maternal gravitas that the role demands, and she sang with a warm and full-bodied instrument. A rich, sophisticated and complicated sound to match her character’s idiosyncrasies. The portrayal was extraordinary, expressing Madeline’s dignity, sometimes real, sometimes composed, and constantly maintained despite her errors, weaknesses and embarrassments. A woman in denial is a very difficult thing to portray, and Pulley accomplished it perfectly. In the third act, when her character transcends that denial, Pulley’s performance was revelatory.

Buried within the remarkable libretto to this story, each character goes through a journey of development, the  children realizing that the weaknesses and drawbacks they perceived in their mother were there of necessity just as they soon began to take on some of those very weaknesses themselves. This was accomplished very well in the acting, in Pam Lisenby’s costume design and in Sondra Nottingham’s subtle but expressive makeup design. In this, I think there is a small weakness in Heggie’s score. In the vocal lines beautiful melodies occur throughout the score. However, there is very little apparent development in the vocal line to reflect the aging and life experiences of these characters across the three-decade interval. Perhaps he chose to focus mainly on the synchronic expression in line, or maybe exemplify the idea that with our families we always fall back into the roles we’ve always played. Ultimately, from a dramatic and emotional standpoint, watching the ensemble numbers was the most difficult. The scenes abound with personal and painful attacks, the moments that mark the typical American holiday dinner, setting up for a latter intimate, if not complete, resolution. Maestro Williamson led the small orchestra from a keyboard with precision and a strong grasp of Heggie’s lines. In all it was another beautiful production from Nashville Opera, and we are looking forward to The Tales of Hoffmann in April.

children realizing that the weaknesses and drawbacks they perceived in their mother were there of necessity just as they soon began to take on some of those very weaknesses themselves. This was accomplished very well in the acting, in Pam Lisenby’s costume design and in Sondra Nottingham’s subtle but expressive makeup design. In this, I think there is a small weakness in Heggie’s score. In the vocal lines beautiful melodies occur throughout the score. However, there is very little apparent development in the vocal line to reflect the aging and life experiences of these characters across the three-decade interval. Perhaps he chose to focus mainly on the synchronic expression in line, or maybe exemplify the idea that with our families we always fall back into the roles we’ve always played. Ultimately, from a dramatic and emotional standpoint, watching the ensemble numbers was the most difficult. The scenes abound with personal and painful attacks, the moments that mark the typical American holiday dinner, setting up for a latter intimate, if not complete, resolution. Maestro Williamson led the small orchestra from a keyboard with precision and a strong grasp of Heggie’s lines. In all it was another beautiful production from Nashville Opera, and we are looking forward to The Tales of Hoffmann in April.

The Nashville Symphony Presents Russian Masters

On Saturday, November 3, the Nashville Symphony gave a performance entitled Russian Masters, featuring guest conductor Victor Yampolsky, the perfect conductor for the program. The concert consisted of three pieces by three very different Russian composers, opening with Dawn on Moscow River from the opera Kovanshchina by Modest Mussorgsky, arranged by none other than Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, followed Tchaikovsky’s famous Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor for Piano and Orchestra, featuring internationally-renowned soloist Behzod Abduraimov. The evening was then ended with Dmitri Shostakovich’s lengthy and tumultuous Symphony No. 8 in C Minor.

Modest Mussorgsky began the composition of his opera Kovanshchina in 1872, but left the work largely unfinished at the time of his death in 1880. What Mussorgsky left was heavily edited by Rimsky-Korsakov, making the work sound much more like–well, a composition by Rimsky-Korsakov–rather than what Mussorgsky intended. Despite the rather dark, political topic of the opera, this prelude is meant to convey just what the title suggests: the hopeful dawn of a new day on the Moscow River.

The light, woodwind and string-dominant orchestration characteristic of Rimsky-Korsakov was made apparent from the minute Maestro Yampolsky gave the first cue, and the players executed it effortlessly. Beautiful woodwind solos wound their way in and out of string melodies and pianissimo chords so delicate that one would almost have to lean forward in one’s seat to hear it all. A darker, Russian-esque march took over in the middle of the piece, showcasing the lower-end of the orchestra’s range for the first time in the evening. Almost as suddenly as it came, the darkness dissipated back into the same delicate character as the beginning, perfectly setting the stage for the rest of the evening.

Tchaikovsky composed his first piano concerto between the years of 1874 and 1875, a time in which he desperately needed a highly successful premiere. This concerto delivered; it was premiered by pianist Hans von Bülow in Boston, and was thankfully very well-received. As the concerto became extremely popular after its premiere in the United States, Tchaikovsky himself conducted the piece at the inaugural concert of Carnegie Hall in 1891.

This technically demanding concerto was performed with elegance and ease by soloist Behzod Abduraimov. Although he is relatively young, he played with the maturity and virtuosity of a musician who is much older, and by default has had much more experience. The technical prowess and raw emotion exhibited in his playing mesmerized the audience from the moment his fingers first struck the keys, and did this concerto justice, to say the very least.

The tone of the piece was perfectly set by the opening in the brass section, followed directly by the majestic, ringing piano chords layered over the ever-beloved melody presented by the strings. The cadenza that followed was performed with such sensitivity and energy that it was impossible to look anywhere else in the concert hall but directly at Abduraimov. The switches in character and texture were beautifully executed by all members of the orchestra and the soloist, creating a wonderful, conversational feeling throughout the first movement (and the entirety) of the concerto. Abduraimov flew through every technical passage with absolute ease and musicality, making it all the more impressive with each passing phrase. He even received a standing ovation by a handful of members of the audience after just the first movement, which was probably equal parts his impressive performance and the sheer length of the first movement alone.

The second movement brought more awe-inspiring displays of emotion and skill by the soloist, as well as beautiful solos from members of the wind section. The Prestissimo portion of the movement was both technically impressive and musically interesting, transitioning effortlessly back into the beautiful melody presented at the start of the movement.The same impressive technique and energy was carried throughout the entire final movement, holding the audience’s attention until the final chord. The grand ending of the movement was so full of energy that it propelled everyone in the hall out of their seats into a lengthy and heartfelt standing ovation.

Shostakovich began composing his Symphony No. 8 in 1943 after a huge boost in his status following the premiere of his Symphony No. 7, “Leningrad.” Shostakovich described his Eighth as a “positive life-affirming work” that carried a theme of “looking forward into the postwar era,” but it feels as though it is more of a Requiem, possibly lamenting the suffering of the World War II years and the victims of Stalin’s infamous purges.

It was truly something to experience a work of such epic proportions, both in orchestra size and length of the piece. This is the first of Shostakovich’s symphonies to boast a length of five movements, which is very interesting. Both an extended wind section and an extended percussion section are always exciting to see, and provided additional volume and color that added so much energy to the peaks of the symphony.

The lengthy first movement of the symphony was executed appropriately, maintaining the somber and moody atmosphere throughout. The Reqiuem-feel is very apparent in this movement, dominated by forlorn-sounding strings. Excellent and shocking shifts in texture sprinkled interest throughout, ranging from bombastic full-orchestra climaxes to sparse, delicate, and highly exposed soloistic passages.

The second movement was a strange and unnerving, yet refreshing and upbeat character shift from the first movement. This movement was definitely more technically challenging than the first, with an absolutely virtuosic and effortless piccolo solo by Gloria Yun extending throughout a fair portion of the movement. The orchestra charged on with an almost manic energy until the very end, leaving the audience a bit anxious and unable to predict what was to come.

The low string section, namely the violas, gave an energetic and driving start to the third movement, once again giving an unexpected shift from the previous movement. Towards the end of the movement an excellently executed trumpet and snare drum duet added to the war-like feel of the symphony, segueing into huge full-orchestra chords topped with appropriately-screeching woodwinds and ear-splitting percussion.

The fourth movement begins just as rowdy as the end of the third, but soon fades into the same quiet, somber mood as the first. The somber mood was once again held steadily throughout by the orchestra, staying true to the Requiem feel that Shostakovich intended.

The fifth and final movement of the symphony was started with a beautiful theme in the bassoon, which was played so elegantly. Soon after begins a very slow, anxiety-riddled build to the symphony’s climax, which is oddly far from the end of the work. Although Shostakovich claims that this symphony represents triumph and victory, it goes out with a fizzle rather than a bang. Soft, subdued chords were sustained beautifully by the orchestra, holding the audience’s attention until the final chord stopped ringing.

Although a lengthy program ended with an unusual symphony, the title Russian Masters truly described the evening: three masterful composers, a masterful soloist, a masterful conductor, and a masterful performance through and through.

Halloween with Nashville Ballet

For sometime the Nashville Ballet has had a penchant for celebrating the Holiday season. No, I’m not talking about the Nutcracker and sugar plum fairies. I’m talking about murder (Lizzie Bordon), haunting (The Raven), witches (Something Wicked), and the undead (Dracula). The holiday is Halloween, and this year is no different with their most recent production of Seven Deadly Sins (concept and choreography by Christopher Stuart) and Superstition (a choreography by Jennifer Archibald setting a composition by Nashville-based composer Cristina Spinei). While  both pieces are reprises of previous productions, the performances on Saturday night were fresh and exciting, revealing not only the strength but also the depth of Nashville’s premiere Ballet troupe.

both pieces are reprises of previous productions, the performances on Saturday night were fresh and exciting, revealing not only the strength but also the depth of Nashville’s premiere Ballet troupe.

Archibald and Spinei’s Superstitions abstracted the “specifically Southern Italian (Sicilian and Calabrese) superstitions” that inspired Spinei in this composition. Focused on coupling, Archibald’s choreography was a revelation in the way she stripped the dance of its performed gendered expectations, (eg. men lift and women are lifted, men lead and women follow, etc). However, instead of being reactionary (women being men and vice versa) she reimaged the couple and ensemble moments as a more fluid and shared responsibility in balance—the women and men were both put into positions that showed strength and grace. Set for cello, violin, piano and electric bass, Spinei’s score is contemporary in a third stream sort of way. It seems that her music is increasingly reflective of her presence in and awareness of the diversity of music here in Music City.

Jon Upleger (Protagonist) and Mollie Sansone’s (Agatho) reprise of Seven

Deadly Sins was, if anything, better than its premiere in 2016. A morality play set to whose concept is set to music by k. s. Rhoads and Ten Out of Ten, each track dealt with its own sin in a different way, but always through lived experience instead of morality. It was on the dance floor that the sins were, in effect, made flesh and yet abstracted. Sarah Cordia’s “Pride” was malicious while Julia Eisen and Julia Mitchell’s “Lust” was fantastic. Remarkably, the impossible part of the product, depicting gluttony by a group of ballet dancers was well achieved by Brett Sjoblom and the Full Cast. The music is always very well done by Ten Out of Tenn and I hope that this collaboration will continue into new projects.

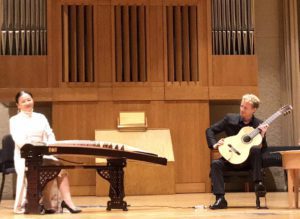

Johannes Möller’s “Chinese Impressions” at MTSU

This free concert was presented by the MTSU Center for Chinese Music and Culture. Guitarist and composer Johannes Möller gave a performance in MTSU’s Hinton Hall. Möller is from Sweden and living and teaching in Amsterdam while traveling and performing all over the world. His interest in world musics has led to projects of recording and writing in Indian and Chinese styles as well as others.

Dr. Mei Han, Director of the Center, introduced Möller to the audience and, noting the frigid temperature of the hall, charmed them by saying “our guest’s beautiful tone will warm your hearts.” The scene was set with a zheng (Chinese long zither to be played by Han), a stool and guitar, and a small, round, wooden table Möller occasionally used as a music stand.

The opening work “The City of Guitar” is a dedication to the Chinese city Zheng’an, where Möller visited in the last year and is now ambassador for Zheng’an guitars. According to the program information, it is a city dedicated to guitar making and has a museum, tower, and concert hall dedicated to guitar. The piece is a lovely miniature, with a light theme returning in an ABA form. It was an enjoyable opener which Möller played with exquisite tone. An attachable pickup wired to the hall sound system gave the guitar a volume boost but did not hinder Möller’s ability to play expressively. His second original piece put the amplification to the test with swelling tremolo and dynamic rasgueado. It was a beautiful sonic painting with a low E ostinato providing stability.

Möller then introduced a set of three Francisco Tárrega pieces from the traditional classical guitar repertoire. He spoke of the Alhambra in Spain and its many fountains and described the famous Recuerdos de La Alhambra piece as imitating dripping waters. This imagery foreshadowed nearly all of the Chinese music that followed in which they depicted various natural scenes. “Maria” was almost aggressive enough with glissandos executed with perfection while “Lagrima” was treated gently and passionately. By the time Recuerdos was performed, I was confident it was in the hands of a virtuoso and relaxed to enjoy a colorful interpretation with flawless tremolo technique.

Fans of modern fingerstyle guitar playing which includes percussive string slaps, harmonics, and tapping will love Möller’s 2018 album Eternal Dream. He performed four selections in Monday’s program and surely surprises classical guitar audiences with them. Compositional aspects include alternate tunings, syncopated rhythms, and melodies in the low register of the guitar.

“My Homeland” is a beautiful arrangement of a traditional Chinese song from the album “China” and is published in sheet music form. It preceded a duo performance of Liuyang River for zheng and guitar which could only be topped by another duo performance of Moonlit Night on Spring River. Originally a Pipa solo, this traditional Chinese piece is very well known. According to Möller, it is to Chinese music what Recuerdos de La Alhambra is to classical guitar music.

After performing together, Dr. Mei Han and Johannes Möller embraced and received well deserved applause. She then reminded him of the set of Chinese Impressions he had skipped in the program and he graciously sat to perform them, apologizing for his jet lag! These three original compositions were Möller’s impressions of China and Chinese music and are well worth hearing. The performer seemed most intimate with this set of music and played with many changes in color and tone. The final impression “Grains at harvest is the farmer’s joy” was bursting with joy at an allegro tempo.

Programmed as the finale, Night Flame is an original composition from the India (2016) album. Möller explained that a raga is composed within certain parameters and he enjoyed this challenge. Contrasting with the Chinese music, Night Flame was dark, more dissonant, and characteristically Indian sounding. It was not as virtuosic as expected, except for some arpeggio passages, but then again not much of the program was virtuosic. Only Möller’s phenomenal tone stood out through the entirety of the concert. A cadenza of rasgueado moving chords and fast descending passages brought the piece to an end. It was a captivating concert and a unique bridging of two sonic worlds, guitar and eastern music.

After both Han and Möller received a bouquet each, they performed an anthem for National Day in China which falls on the first of October every year.

Nashville Symphony Unveils Lineup for Free Day of Music 2018

13th annual event takes place on Saturday, October 27

with 25 performances, beer garden, food trucks, family activities, ticket discounts and more

Nashville, Tenn. (October 8, 2018) — The Nashville Symphony has released the full lineup of performers for Free Day of Music 2018, taking place on Saturday, October 27, from 11 a.m. to 9 p.m. at Schermerhorn Symphony Center.

The 13th annual event – part of the Nashville Symphony’s commitment to making music accessible for everyone in Middle Tennessee – will include 25 free performances on four stages, featuring everything from classical and jazz to rock and country.

The GRAMMY®-winning Nashville Symphony kicks off the festivities with a free concert in Laura Turner Concert Hall at 11 a.m., and the full schedule for the day is as follows:

Laura Turner Concert Hall

11 a.m. – Nashville Symphony

12:45 p.m. – Music City Brass Ensemble

2:15 p.m. – Nashville Symphony Chorus

3:45 p.m. – Organ Recital with Andrew Risinger

5:15 p.m. – Nashville Philharmonic

6:45 p.m. – Gale Mayes & Friends

8:15 p.m. – Nashville Salsa Machine

One Symphony Place

12 p.m. – Sonja Hopkins Jazz Band, presented by the National Museum of African American Music

1:30 p.m. – 5 Points Swing

3 p.m. – Quiet Entertainer

4:30 p.m. – Vicki Reid Band

6 p.m. – Choro Nashville

7:30 p.m. – Lars & Laura

Curb Education Hall

12 p.m. – Q&A with Nashville Symphony Assistant Conductor Enrico Lopez-Yañez and Nashville Symphony Chorus Director Tucker Biddlecombe

1:30 p.m. – Student ensemble from the Nashville Symphony’s Accelerando program

3 p.m. – MET Singers

4:30 p.m. – Nashville in Harmony Chorus

6 p.m. – Chatterbird

7:30 p.m. – Misha Robledo

Courtyard Stage

12 p.m. – Avalon Mirabel, presented by YEAH!

1:30 p.m. – Wu Fei

3 p.m. – The Front Steps

4:30 p.m. – J Pierson, presented by Southern Word

6 p.m. – Alison Brazil & the Roots of Rhythm

7:30 p.m. – Belmont Bluegrass Ensemble

Free Day will also feature:

- Halloween and Day of the Dead themed family activities, presented in collaboration with Conexión Américas and Kidsville, including face painting, a costume contest with ticket giveaway and more.

- Enhanced accessibility and sensory-friendly offerings throughout the day, including quiet spaces, ASL translators for select performances, and other supports.

- The Symphony’s popular Instrument Petting Zoo, which offers music lovers of all ages a chance to try out a variety of musical instruments (11:45 a.m. –3 p.m.).

- Some of Nashville’s finest food trucks, in collaboration with Mesa Komal from Conexión Américas, including Burritos La Mina, Oliver’s Ice Box, Two Peruvian Chefs and a Truck, Two Thompson’s Airstream.

- No handling fees on all concert tickets purchased at the Schermerhorn Box Office.

- A spooky story corner presented by The Bookshop (11:30 a.m. – 4 p.m.).

- An outdoor beer garden presented by Craft Brewed.

- A photo booth.

More information about Free Day of Music activities and all event performers

is available at: NashvilleSymphony.com/FDOM

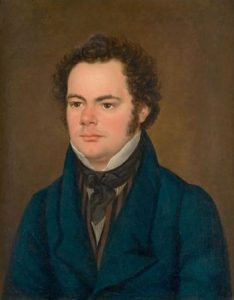

The Nashville Symphony in Fine Form with Haydn, Schubert and Martin

The program presented by the Nashville Symphony on October 12th, may not upon initial consideration generate an obvious theme for an evening of orchestral music. Haydn’s Symphony 104 “London,” Schubert’s Symphony No. 8 D. 759 in B minor “Unfinished,” and the Concerto for Seven Wind Instruments and Timpani by 20th century composer Frank Martin don’t share any obvious connections. But, a consideration of the compositional devices and organizational elements presented in these works paired with the nuanced interpretation of the Nashville Symphony under the direction of Maestro Guerrero, afforded listeners the opportunity to enjoy an evening of superb musicianship through the vehicle of a thoughtfully crafted program.

The evening began with Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony, a piece that in only two movements takes listeners through a carefully orchestrated dramatic juxtaposition of light and dark with a heavy dose of the contrasts and harmonic manipulation present in much of his lieder. Schubert composed these two movements in 1822 at the age of twenty-five, and though he finished many other works including a ninth symphony before his death in 1828, the eighth symphony remained “unfinished.” Some scholars have suggested that after becoming terminally ill shortly after completing these movements, Schubert had difficulty working on a piece that he may have associated with his own sense of mortality. But, he had little trouble musically confronting the inevitability of his own death as evidenced by his string quartet no. 14 (1824) which recycles melodic material from his “Death and the Maiden” (1817), a lied that addresses the eventual acceptance of death via harmonic transformation. Why then did Schubert not “complete” the eighth symphony? Perhaps it is because the strength and narrative flow of the two finished movements form a complete musical statement that will not easily permit continuation. Though with only two movements it doesn’t follow conventional symphonic form, Schubert’s “unfinished” symphony is a crowd pleaser and is routinely performed as a stand-alone work. Had he not died in 1828, the later popular romantic vehicle of the symphonic poem would have held untold potential for Schubert.

The “unfinished” symphony allows listeners to experience the harmonic, melodic, and structural developments Schubert had long exhibited in his lieder within a larger symphonic context. In the first movement, the stark contrasts of the harsh minor themes conjured forth by the dark opening statement and the soft spoken light-hearted thematic gestures that follow, require a rapid shift in character, and the ensemble was equal to the task. The dramatic pauses used to punctuate some of these changes, often stopping lyrical content in what seems like mid-sentence, were masterfully handled by the orchestra. One could almost see the audience leaning forward in anticipation of the downbeat we all knew would arrive, but were happy to delay in order to share together the silence of perfect expectation. Schubert’s harmonic shape in the second movement is a broad inversion of the first, with an initial major theme followed by a minor theme that eventually snakes its way harmonically back to the original key for an ending that may be characterized as peaceful, but not subdued. It may not exist in a standard four movement structure, but Schubert’s “unfinished” symphony has the strength to stand alone.

Schubert’s emotionally charged offering was followed the Nashville Symphony’s premiere performance of Swiss composer Frank Martin’s Concerto for Seven Wind Instruments and Timpani (1949) featuring Érik Gratton (flute), Erik Behr (oboe), James Zimmerman (clarinet), Julia Harguindey (bassoon), Leslie Norton (horn) Jeffrey Bailey (trumpet), Paul Jenkins (trombone), and Joshua Hickman (timpani). Treating each of the orchestra’s standard wind instruments (with the exception of the tuba) and the most commonly used percussion instrument as soloists, at once calls to mind a possible interplay of the expectations of the traditional coloristic roles they occupy and a concerto grosso format allowing individual voices and subsets to shine. Within a modern aesthetic, the sometimes blocky baroque concerto grosso can limit the interaction between the soloists and the ripieno group – outlining a clear definition of what “should” be important to the listener. But, Martin’s approach draws on elements of tradition while treating each solo instrument as its own tone color, allowing the character of the instrument and the player to dictate the development of the work. Through his choice of soloists and his construction featuring color and characteristic as structural components, Martin has married the concepts of the traditional function of symphonic winds with the soloistic nature of the concerto grosso, all within a traditional three movement concerto structure.

Martin’s allusions to baroque tradition are perhaps most easily seen in the second movement through his use of a clearly articulated and unchanging rhythmic foundation and repetitive string entrances between the soloists’ lines. The jagged lines and technical fireworks of the first movement give way to a lyrical virtuosity in the slow second movement, allowing the soloists to sing. Martin’s rhythmically static accompaniment forces listeners to focus on the longer solo lines, and though the rhythmic figures are steady, Martin subtly alters his accompaniment’s range and timbre to mirror the characteristics of the solo instruments. This is most clearly heard in the initial high bassoon melody hauntingly played by Julia Harguindey, and its darker repetition beautifully expressed by Paul Jenkins on the trombone. Each statement features an individualized setting for these two colors. The movement concludes with a sublime tapered sigh at the end of the trombone solo, inviting the audience to slowly exhale along with the orchestra.

The virtuosity displayed by the soloists was staggering. Gratton, Behr, Zimmerman, and Harguindey effortlessly navigated thorny and angular lines, while the fanfare gestures played by Norton, Bailey, and Jenkins were clean, crisp, and brilliant. Frank Martin even carved out a space for a timpani solo, allowing Joshua Hickman to weave a dynamically varied melodic statement that instead of acting as a predictable “drum break”, instigates an eventual role reversal allowing the soloists to provide a syncopated accompaniment against the soaring string section. The work ends much as it begins with the solo contingent leading an impressively dizzying charge toward a climactic punctuation.

The evening concluded with Haydn’s last symphony, “London” no. 104, (1795). The “Father of the Symphony” needs no introduction, but it bears mentioning that his symphonic output provided the model that many composers followed. Specifically in his later works, Haydn’s use of the process of musical form to express the elegance and possibilities of a musical idea’s transformation rather than a treatment of form as a mold to simply fill, resulted in some of his most popular

works. It is fitting then that maestro Guerrero elected to end a concert of non-traditional forms with a defining work from a composer who both served to establish and expand the process of form within a symphonic setting.

Though the audience and performers were all comfortable with Haydn’s familiar work, the orchestra’s interpretation and enthusiasm kept the piece fresh. Maestro Guerrero’s bright tempo in the last movement allowed the finale to act as a true endcap for the evening. The character of the movement is folk-like after all, and the brisk pace permitted the orchestra to shout, sing, and whisper the iconic melody with rollicking glee.

Perhaps a concert organized around the concept of musical form is a stretch for some listeners, and by all means the superb musicianship alone was worth braving the downtown Nashville traffic. But, for the nerdy music fanboys among us who smile and push our glasses further up the slopes of our noses at the bare mention of Schubert and chromatic mediants, this kind of programming could only have been an artistic and intentional choice.

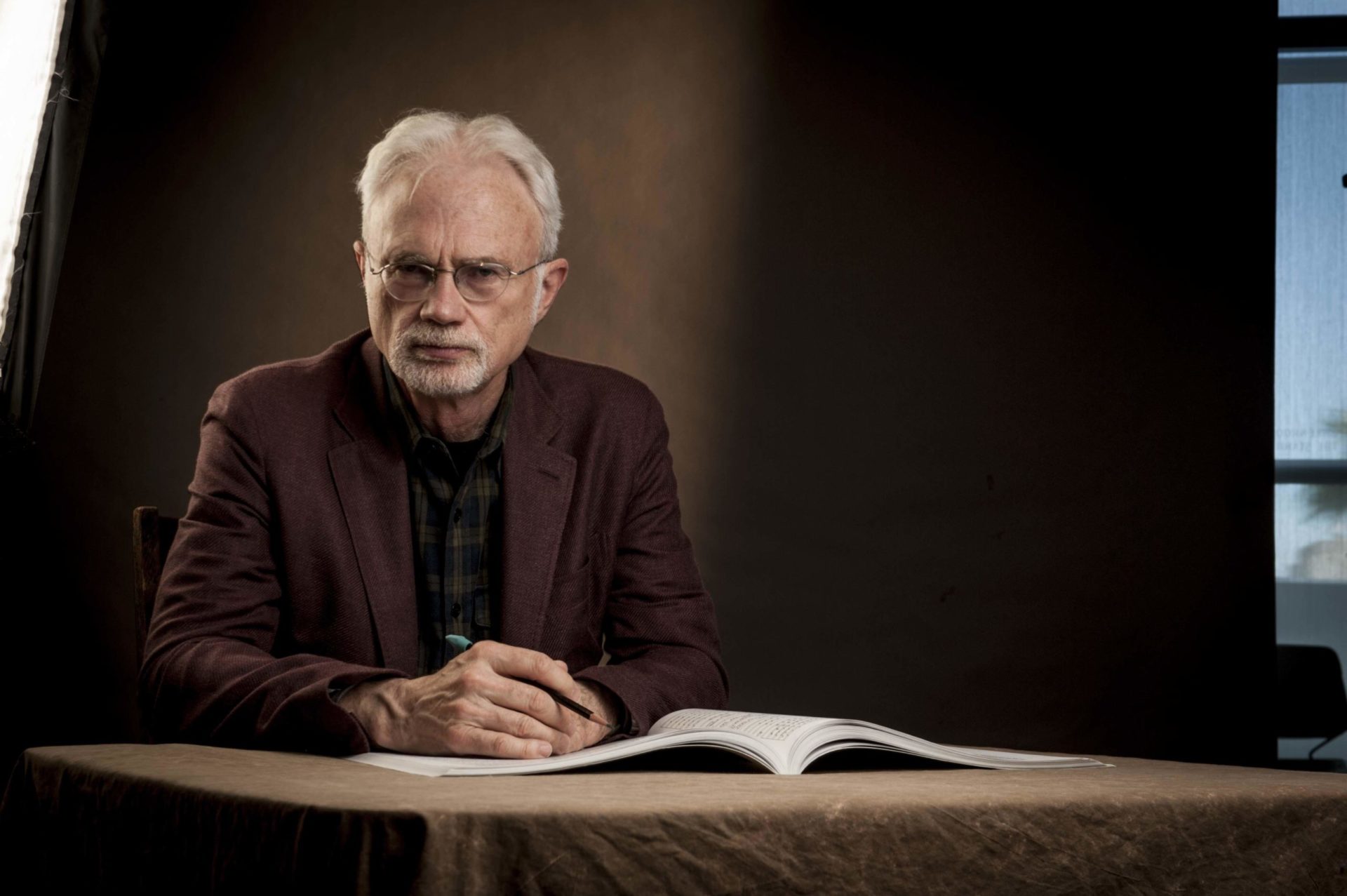

Adam’s Harmonielehre and Ehnes Plays Beethoven with the Nashville Symphony

On Sunday, October 7, 2018, the Nashville Symphony gave a performance of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D Major, featuring international soloist James Ehnes, and John Adams’s orchestral masterpiece Harmonielehre.

Beethoven composed his only (finished) violin concerto in 1806 for the Austrian violinist Franz Clement. Clement gave the work its premier performance at the Theater an der Wien on December 23, 1806. There is a story, the validity of which is uncertain, that Beethoven completed the score so late that Clement had to read the part for the first time in the premier performance. This may explain the initially poor reception of the piece, which continued to float by unnoticed and under-performed until the young Joseph Joachim brought the piece recognition, 17 years after Beethoven’s death, in 1844 with a performance under the baton of Felix Mendelssohn.

While having its moments to the contrary, Beethoven’s Concerto is not a greatly technically demanding piece of music, though its requirements of musical awareness, sensitivity, and judgment from the soloist are close to unparalleled. James Ehnes’s years of experience really shone through in his performance on Sunday. His interpretation, while on the more conservative side, never lacked interest from the audience nor, evidently, the performers.

From the first passage soloist played, Ehnes owned the hall. The concerto denies the audience the typical moment in the form where the soloist would enter playing the primary theme, instead giving an almost frustrating dance around arpeggiated dominants and scalar figures before finally giving the theme. Ehnes took full advantage of this longing and set a precedent of gorgeous tone (thanks in part to the “Ex-Marsick” Stradivarius violin with which he performs), sensitivity, and wit. The second movement began with another excellent example of Ehnes’s awareness and sensitivity. The exchanges with the orchestra seemed without flaw. The second movement concluded with a cadenza that led straight into the excitement of the rondo, the highlight of which was the big cadenza of the third movement. Ehnes performed Fritz Kreisler’s cadenza with great clarity and virtuosity, generating excitement that drove through until the drop of Maestro Guerrero’s baton.

The intermission was much needed after such an intellectually engaging performance. That said, I walked back into the hall filled with excitement about the piece to follow.

John Adams’s Harmonielehre was written in 1985 as a culmination of a residency he held from 1982 to 1985 in San Francisco. The name, Harmonielehre, comes from a textbook with the same name by Viennese composer Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg is famous, or infamous to some, for diverging from the concept of tonality. He developed a system that is commonly referred to as “twelve-tone music.”

Being a composer in the latter half of the twentieth century, one has to respond in some way to atonality and specifically Schoenberg’s ideals. John Adams responds quite directly, saying, “Despite my respect for and even intimidation by the persona of a Schoenberg I felt it only honest to acknowledge that I profoundly disliked the sound of twelve-tone music.” The title is, obviously, an ironic homage to, and response to, Schoenbergian ideals.

Adams says that Harmonielehre is the product of a series of dreams of his. The first movement is based on a dream in which Adams saw an oil tanker on the waters of the San Francisco bay. In his dream, the ship takes off to the sky. The second movement, The Anfortas Wound, is based on C.G. Jung’s writing on the medieval character Anfortas. The third movement, Meister Eckhardt and Quackie, is based on a dream about his, then infant, child, Emily, who he had nicknamed Quackie. Adams dreamed of Quackie flying around with Meister Eckhardt, a German philosopher, and being told the secrets of happiness.

The first movement begins with a strong statement of repeated e minor chords, 39 of them in fact, in a very minimalist gesture, the beginning of an “inverted-arch form.” The second movement is reminiscent of composers such as Sibelius and Mahler, with a particularly specific reference to Mahler’s tenth symphony. The third movement is in Eb major, a startling difference from the strong E minor center established in the first movement.

Maestro Guerrero’s interpretation was tasteful to say the least. The big e minor chords can often be overdone by an orchestra, but the symphony’s range of the effects were never overbearing, but were engaging and drove the form into the audience. By the middle section of the arch, the audience was clawing for the neoromantic lyricism that followed, and then returned to the decidedly minimalist exterior with intensity, but sensitivity for the need of the listener.

The second movement was stolen by the principal trumpet, Jeffrey Bailey. The dense surrounding areas of the solo were gorgeous, heart-wrenching chords that set a perfect background over which the trumpet could, and did, soar.

The third movement radiated with the joyous hope one would expect from Eb major. With the mystic nature of the writing, the audience was transported straight into Adams’s dream of his daughter, floating ethereally through this soundscape hearing Adams’s prescription for happiness: minimalist techniques blended seamlessly with mid- to late-romantic ideals. The tension mounted about two thirds of the way through the movement, propelling the audience to the cacophonous ending of the piece, with the trumpets soaring over a very pointed background until the glorious, if not sudden, arrival of the Eb tonic.

The Nashville Symphony was recording the Adams for a CD release through the publishing company “Naxos of America.” A CD that I excitedly await purchasing. The Nashville Symphony returns with a public concert at the Renaissance Center on October 20th, 2018.

La Traviata at Nashville Opera

In 1852 Giuseppe Verdi began composing his great La Traviata for the next season’s Carnival in Venice. The libretto was written by Francesco Maria Piave after Alexandre Dumas’ play La dame aux camélias, and premiered on March 6, 1853. Dumas’ tragic narrative is a semi-autobiographical account of his own relationship with Marie Duplessis who died of consumption shortly after their relationship ended. On October 4th, Nashville Opera opened its season with a performance of this, perhaps Verdi’s most romantic opera, at the Tennessee Center for the Performing Arts.

The best part about Verdi’s operas, as with most Italian operas, are the vocal numbers and La Traviata is no different. For this production they brought in American Soprano Emily Birsan and Korean tenor Won Whi Choi. While the two singers were not perfectly matched, their strengths led to some magical moments in the production. Birsan, who has a bright and delicate voice was particularly magnificent in the second act in the moments when she is in love with Alfredo and by the third act when her illness takes over. For Choi’s part he has a tremendous instrument with a bright, brassy sound. In the famous first act drinking song,

“Libiamo ne’ lieti calici” he was magnificent. In the party scenes, Birsan’s portrayal of Violetta as the life of the party was alluring, and well matched by Choi’s fetching glances.

The supporting cast, including the Baron, (Baritone Jeffrey Williams), and Doctor Grenvil (Bass, Ben Troxler) were all very strong. As always Amy Tate William’s choir was well prepared and the orchestra was flawless under Dean Williamson’s baton—in particular it was fun to hear and see the cimbasso in the horn section. In all is was an outstanding production and well worth a Thursday night out. Nashville Opera returns in early November with Jake Heggie’s brilliant Three Decembers.