Something New, Now and Then: Novel Noise with ALIAS

For classical music’s younger audience and artists, a distinctly pressing question can frequently come to mind. It is a simple one that seems like it wouldn’t be so frustrating when taken at surface value, but I would risk saying many musicians and enthusiasts my age have come across it more than a few times by this point in their engagement of classical music. The pest of a question: Where can I hear something new? Recital environments can have a predictably standard literature. Symphony Orchestras keep up a constant rotation of Beethoven, Bernstein, Mahler, and any other name out of the old guard; occasionally tossing in the score of a film or video game to help keep the lights on. Opera companies roll out any two Mozart favorites per season. None of this, of course, is necessarily a bad thing. Such masterpieces are beloved for a reason and it is hard to get truly bored of them. Still, there is a feeling in hearing something you have never come across before that is undeniably magical. On Tuesday night, June 4, 2019, in the intimacy of the sanctuary of a synagogue, the chamber ensemble ALIAS offered a stirring answer to such a problem.

As the conclusion to their 17th season, and the latest installment to their Novel Noise series, ALIAS played a program that was delightfully underpinned by a unique kind of freshness; the careful juxtaposition of old and new. Even well-loved standards in chamber music repertoire were colored by new and thoughtful interpretations. Pieces as aged as J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion were programmed right alongside two world premieres, both featuring electronic instrumentation as their centerpieces.

The night opened with “Erbarme Dich” from the above-mentioned St. Matthew Passion, followed without much pause by John W. Work’s arrangement of “This Little

Light of Mine” by Harry Dixon Loes. Both were performed by countertenor Patrick Dailey and a string trio of violin (Zeneba Bowers), cello (Matt Walker), and theorbo (Francis Perry). The trio performed in baroque tuning and used baroque bows, which gave a very unique color to the more contemporary sound of Work’s “This Little Light”. Dailey’s soaring countertenor ebbed with the trio exquisitely and overflowed with expression. While sometimes not perfectly in control, the color and spin of Dailey’s singing landed with heartbreaking beauty. One can also appreciate the clever programming; where an aria on Peter’s denial of Jesus is followed by the evangelical poem of “This Little Light of Mine”.

“Lihim”, a cello quartet by Larissa Maestro kept the deeply expressive warmth of the night going with frequent pauses and unpredictable but satisfying harmonic turns until its conclusion; warm and resolute, but with no compromise in tension. It gave a nearly cyclical impression of joy and melancholy, delicately expressed in the capable hands of the quartet. It was followed by Dmitri Shostakovich’s “Two Pieces for String Quartet”. The works of Shostakovich often find themselves performed with a degree of force and bombast. ALIAS’s interpretation left it out, favoring a heightened nuance in the two pieces. The first of the two, the Elegy, came with quiet calculation that felt like genuine weeping. The second, a Polka, could just have easily fallen victim to the excess of smirking growling that comes to the American mind when presented with Russian pieces. Instead, ALIAS found all of the piece’s engrained humor, smiling at each other and giggling in the most refreshing way.

“A Tree of Life”, a trio for clarinet, cello, and piano by Michael Alec Rose, weaves Ashkenazic musical tropes taught to Jewish children into a spiraling, turning, and at times prickling post-tonal landscape. The result is one of paradox where old melodic content clashes against new harmonic ideas. It combines into a deep impacting meditation on the confusing nature of spirituality in a new and unfamiliar time. As it was beautifully performed by the trio, I only wish I had a greater personal familiarity with the melodies themselves to fully grasp there relationship to the surrounding textures.

The final two pieces were in their premier performance and brought, by far, the most surprising pallet of sounds. “Freya” by Kris Wilkinson and Tim Lauer is a musical depiction of the title goddess; a goddess with paradoxical associations of death, fertility, war, beauty, wealth, and magic. The resulting musical ideas carried all the allure of its programmatic source, and listeners are sure to feel an overwhelming sense of both beauty and danger. At the heart of the piece was a host of electronic instruments. Using an Omnichord, a Theravox, a synthesizer, and an electric kalimba, Wilkinson and Lauer create an environmental texture that could never be found with standard instrumentation. The combination of instruments lends a mysterious fog to each sound and builds a distinct expressive core for the piece. Violinist, Alicia Enstrom, added an incredible color with playing that seemed to alternate between orchestral nuance and the growl and grit of a Nordic Hardanger fiddle. Together, the

pAlicia Enstromassorted elements create something that is both modern and viscerally primal. “Thrash Early” by Jesse Strauss continued the new pallet of sounds provided by electronic instrumentation. Built off the vibraphone and marimba, the addition of sensory percussion and a modular synthesizer created a cavernous, mystifying

ambience. The opening section lured in the audience with no traceable sense of meter and true expressive fluidity. This soon gave way to a pulsating, rhythm driven second section, focused on a haunting and vivid melodic figure and peppered with sub-bass swells in the synthesizer. The integration of modular synthesis added a special layer of intrigue, as every bizarre manipulation of sound happened before the audience’s eyes in real-time. Both premier pieces presented a striking answer to what comes next in the world of classical music.

In the end, it was impossible to leave the performance without some sense of genuine awe at what had just happened. Every element felt fresh. Whether centuries old or only made possible by technology introduced a matter of decades ago, each performance kept a perceivable crispness that is rare in other concert material. There is something transcendent about old and new meeting that thrives in the world of classical music, and better still an ensemble that can embody that; that can be both in touch with the traditional, yet exist on the bleeding edge of an art. As nice as old standards can be, nothing is more stirring and essential than hearing something new and unfamiliar from time to time. ALIAS’s performance at Congregation Micah on Tuesday night encapsulated exactly that, and was, in turn, absolutely thrilling.

Classical Reviews

The Nashville Symphony Presents Carmina Burana

On Saturday, June 1, the Nashville Symphony gave a special performance of Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, featuring the Nashville Ballet, Nashville Symphony Chorus, and Blair Children’s Chorus. The program also featured Joan Tower’s Sixth Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman and Jonathan Leshnoff’s Symphony No. 4, “Heichalos.” All four performances were sold out, and with good reason: this was quite possibly the greatest concert of the Symphony’s season.

Joan Tower composed Sixth Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman in 2007, after a nearly 20-year hiatus from composing the other five Fanfares, to honor the Baltimore Symphony’s centennial season. Like the other five Fanfares, this piece was dedicated to a woman who “decided to take risks” and “is adventurous.” Tower’s Fanfares are quite popular, and have been performed by more than five hundred ensembles around the world. Her success doesn’t stop there: Tower was the first woman to ever win the Grawemeyer Award, and the Nashville Symphony’s 2008 recording Made in America, Tambor, and Concerto earned three GRAMMY Awards.

The piece began with a driving ostinato, which was kept steady and delightfully energetic throughout. As more voices were incorporated into the music, the blend and balance of the orchestra was phenomenal and created such interesting timbres. The orchestra also captured every shift in character, every high and low, and transitioned between them with masterful ease and facility. The energy of the ostinato persisted until the very end, which did not feel like a typical, definite ending. While this did not feel like a usual opener, it was very refreshing and well-performed by the orchestra.

Jonathan Leshnoff began the composition of his Fourth Symphony in 2015, and completed it in 2017. The piece was premiered by the Nashville Symphony in 2018, using the

Violins of Hope, a collection of restored string instruments played by Jewish Musicians during the Holocaust. This recording was recently released on CD. The symphony takes the listener on a meditative and spiritual journey once taken by many Rabbis, in which they traveled through “rooms” in order to communicate with the Divine. The music is in two distinct parts: the first, a dark representation of knowing all that happens in the world, and the second, which Leshnoff describes as a “love song between humanity and God.”

The first part opened with an extremely dissonant and emotional opening, which includes an impressive trombone feature that progressed into powerful, full-brass chords. Difficult mixed meter string passages formed the steady, driving motive of the piece, and were executed with ease by the symphony. All of the timbres accurately captured the dark, somber mood, which was convincingly sustained throughout by the full orchestra. A refreshing character shift that featured the masterful blend of the clarinet and piano lightened the mood just before an exciting push to the second part. All of these shifts and emotions were beautifully captured and displayed by the Nashville Symphony, and definitely conveyed the thoughts and emotions of the composer.

The second part opened very differently than the first, and focuses the attention of the audience on the delicate melodies in the strings, particularly the violins. After just a few bars, it was easy to understand why the piece was written for a premiered using the Violins of Hope. The audience seemed to be absolutely captivated by these almost ethereal melodies, and were only brought back to reality as the pizzicato notes in the bass lightly broke the spell. Beautiful blend and balance in the violas and cellos lead seamlessly into the full orchestra’s entrance, and was done so effortlessly by the symphony. The excitement and energy built relentlessly to a triumphant climax peppered with chimes, and was eventually topped again by full, orchestral chords with organ for extra thickness. It was truly an impressive wall of sound that clearly depicted what the composer intended. Soon after, it subsided into the same delicate string melodies and sustained chords as the beginning, and once again captivated the audience until the very end. Leshnoff’s Symphony never seemed to go quite where the audience expected, but the piece definitely did not disappoint, and received a well-deserved standing ovation.

Carl Orff composed Carmina Burana in 1935 and 1936, and the piece was premiered in 1937. Orff’s intention was to include all of the performing arts into one spectacle, and even incorporated backdrops, costumes, and lighting in the performance, and labeled it as a “scenic cantata.” The inspiration for the piece came from an anthology of medieval poems that Orff found in a rare bookstore, entitled Carmina Burana. After its premiere, Carmina Burana was criticized for its graphic sexuality, but also recognized as an example of populist new music during the Third Reich. This, along with Orff’s opportunism during these years, has somewhat tainted the music, although it has remained widely popular and used commercially.

The opening O Fortuna was both extremely powerful and visually stunning. The costuming, lighting, and film by Duncan Copp added so much to the well-known music that it felt as though I was truly experiencing Carmina for the first time all over again. All of the members of the Nashville Ballet danced beautifully and conveyed the story and moods of the piece much better than words and music alone ever could. The music, however, was also fantastic as always. The Nashville Symphony Chorus performed with so much energy, clear diction, and masterful blend. The orchestra sounded wonderful despite being in the pit, and balanced with the Symphony Chorus quite well.

What truly made the performance spectacular, however, was the immersive experience. The film, ballet, orchestra, and chorus combined created such a spectacle onstage, which was complemented by vocalists in other locations around the hall. The Blair Children’s Chorus provided a surround sound-like effect from the back of the hall (with wonderful tone and balance, too!). The three soloists, Valentina Farcas, John Logan Wood, and Stephen Powell, were positioned at different points around the hall, adding more to the experience. I had the pleasure of sitting directly behind Stephen Powell as he sang Dies, nox et omnia in one of the aisles, and it was truly a breathtaking experience.

Words simply cannot do this performance justice. Of all the Nashville Symphony concerts I have attended, this was certainly one of the most interesting and memorable. I am certainly looking forward to more programs like this in the future! There could not have been a more perfect way to transition into the summer season.

Carmina Burana: A Discussion with Steve Brosvik, COO of the Nashville Symphony

Last week, we had the opportunity to speak with Steve Brosvik, the COO of the Nashville Symphony, about the upcoming performance of Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana. Not only does this concert feature both the Nashville Symphony and the Nashville Symphony Chorus, but it also shines a spotlight on the Nashville Ballet, Blair Children’s Chorus, and a handful of talented soloists. It was wonderful and quite interesting to hear what it was like to coordinate this large, spectacular performance from his perspective.

[MCR]: What prompted the decision to involve the Nashville Ballet and Blair Children’s chorus?

[Brosvik]: Carmina Burana is a piece which requires adult and children’s choruses. We have worked with the Blair Children’s chorus for several other works and it made sense to keep that relationship in place for this production of Carmina Burana. We have a long-standing relationship with the Nashville Ballet, primarily focused on the Nashville Symphony playing in the pit for many of the Ballet’s productions each season. A few Ballet companies have their own orchestras and many companies use pre-recorded music. The Nashville Ballet is one of the companies that works with the primary Symphony in its community and we believe it to be a deep, musically fulfilling, and creative partnership. We have explored the relationship in a couple of different ways and this project is the next step in that evolution. We hope that the audience members are as excited about the final product as we are and we hope that this is only one of many artistic partnerships we can foster together and throughout Nashville.

What inspired the decision for a choreographed version of Carmina rather than the traditional staging?

The Symphony has performed the work 11 times since 1957 including three performances runs with the Nashville Ballet at TPAC. This work is an audience favorite and was originally written with the intention that it would be danced. The performance at the Schermerhorn in March of 2016 including Appalachian Spring, Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, and Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet were the first step in seeing how we could stretch the Schermerhorn with the combination of orchestra and dance. Those performances opened a window of creativity for us that we are exploring further with this new production.

Were there any challenges when planning the concert/coordinating with other ensembles? How were the challenges overcome?

This production is a feast for the senses and coordinating all of the elements to form a richly cohesive experience instead of sensory overload had to remain a continued focus. Collecting this particular combination of artistic elements forced us to think through the technical solutions multiple times to find the best arrangement of those elements to give the audience members the most enjoyable experience possible. Where to hang the screens, how to add the additional lighting necessary to create the effects envisioned by the original lighting

This project has stretched us to find new ways of working with each other, to refine what we are already doing, and to discover new ways to make work together in new directions. For instance, the Appalachian Spring performance at the Schermerhorn had both the Symphony and Ballet Company sharing the stage. For Carmina Burana, we are taking advantage of our movable seating system and storing multiple rows of seating in the lower level of the building to create a kind of orchestra pit from where the full Symphony will perform during the second half of the concert. This frees the entire stage to make room for the dancers. The Ballet is bringing their sprung dance floor to be placed over the stage. We needed to take this into consideration when programming the first half of the concert in order to avoid damaging the sprung flooring.

What has been the most rewarding part of watching this event come together so far?

Reaffirming that each time we hit a decision point, that everyone kept putting the quality, creativity, and quality of the project before individual opinion. Our creative relationship is stronger now than when we began.

What will be the most exciting component of this production from the audience’s perspective?

We have coordinated the entire production around the elements and abilities of the Schermerhorn. The audience is going to feel immersed in the experience and directly connected to the music, the dance, and the imagery.

What qualities make this performance an ideal community event? What about this program would appeal to someone that isn’t the average symphony-goer?

I think that everyone knows more classical, or orchestral, music than they know. Carmina Burana is a piece with themes so popular that they are used in movies, television, and commercials. We think this program has something for everybody and think it will appeal to both brand new, and experienced audience members.

If you would want an audience member to know one thing about this production before the performance, what would it be?

The history of the work is fascinating and there is a lot of information about the history of the piece and the poetry on our web-site and around the internet. You won’t need to know any of that to enjoy the performance. If you have a little time, however, understanding a bit of that will only add to the experience.

What kind of community partnerships do you and the Symphony have planned for next season?

We are already working on a very large cooperative project for the fall of 2020. We hope to be able to say more about that soon but, for now, I will just say that the project will combine multiple organizations working on a single project and theme.

By the sound of it, this concert will be highly exciting for all members of the audience! A large-scale performance such as this does not happen very often, so you don’t want to miss out! Carmina Burana will run for four performances, beginning Friday, May 31, and ending Monday, June 3. Tickets are still available for all four nights.

Spectrum: An Eclectic Collaboration at Oz

On May 18 and 19, Nashville’s contemporary music ensemble Intersection collaborated with the choral ensemble Nashville in Harmony to present a concert titled Spectrum at

OZ arts in Nashville. The evening consisted of a rather eclectic collection of pieces culminating with a performance of Those Moments, a special commission from T.J. Cole for a work for choir and mixed chamber ensemble with pre-recorded audio.

The concert began with Nashville in Harmony performing “Until All of Us are Free” and “Why We Sing,” two moving, and culturally conscious selections performed in a dynamically nuanced and expressive manner led with enthusiasm by director Don Schlosser. These are accessible pieces that perfectly fulfill the choir’s mission to “build community and create social change.” In the second number former members were invited to join the choir as they performed a chilling rendition of that anthem.

Next, as the choir exited the stage, the musicians from Intersection entered to perform Esa-Pekka Salonen’s Mania (2000). Mania is a kind of virtuosic vehicle for cello, written for Finnish cello virtuoso Anssi Karttunen, that seems to merge the constant repetition of minimalism with an equally constant and continuous developing variation as the solo

cello fades in and out of a rich and dense accompanying framework. Salonen describes the work as:

I wanted to compose music, which consists of a number of relatively simple gestures or archetypes, which are constantly evolving and changing; not so much through traditional variation techniques, but trough a kind of metamorphosis. A maggot becomes a cocoon, which becomes a butterfly: very different gestalts indeed, but the DNA is the same.

Intersection’s Michael Samis proved himself up to the task with a brisk articulation of Salonen’s rushing gestures, all without losing clarity or feel. Maestra Corcoran admirably maintained a precise balance in the ensemble in a composition that requires sheer virtuosity from nearly every one of its members. At the pause before the applause one could hear the audience join the musicians in catching their breath.

Before intermission Nashville in Harmony returned to the stage to perform three more songs, Christopher Tin’s “Sogno di Volare,” Annie Lennox’s “1000 Beautiful Things,” and Taylor and Dallas’s “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free.” Of the three, Tin’s “Sogno di Volare” (The Dream of Flight) was the most interesting. A theme from the video game, Sid Meier’s Civilization VI, Tin’s choral anthem is a setting of a modernization of Leonardo da Vinci’s writings on flight in which the composer hoped to “capture the essence of exploration; both the physical exploration of seeking new lands, but also the mental exploration of expanding the frontiers of science and philosophy.” The soloists for Lennox’s “1000 Beautiful Things,” Grace Wegener, Paige Pennigar, and Lia Van de Krol were remarkable in their articulation and timbral color, each adding a subtle interpretation from within the color of their individual voices that, on the one hand, emphasized their separate indentities but on teh other, blended quite well within the broader group–a perfect metaphor for Nashville in Harmony’s aesthetic (and political) goals.

After intermission Intersection returned to the stage to perform Liza Lim’s Voodoo Child (1989). Lim’s work is also a vehicle for virtuosity, but not of the traditional sort of virtuosity heard in Salonen’s piece. Lim’s work features extended techniques such as guttural song from the soprano, bi-phonics (two pitches at once) from the clarinet and other non-traditional sounds to create clouds of sound that tended to clash in their expression of the extreme emotive sentiments as drawn from Sappho’s poem To a Young Girl. The result is a kind of synthesis of the sound palates of Edgard Varese and the intense primal expressions of George Crumb. For me this was the most interesting performance of the night. Each instrument displayed extended techniques that reached beyond its expectations even as other gestures seemed to be remarkably idiomatic to each instrument. Special mention for this goes particularly to Alejandro Acierto (clarinet) and Kristen Holritz (flute). Particularly stunning was Rebekah Alexander’s

(soprano) performance. Alexander, through her performances with Chatterbird and now Intersection, is developing a strong reputation for bringing the highest musicality to the most difficult contemporary repertoire for voice. Here she sang with a bracing charisma and personality that moved the audience to the edge of their seats. One hopes we might someday get the opportunity to hear her interpret Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire or even Ligeti’s Mysteries of the Macabre.

Finally, the evening ended with the commission, Cole’s Those Moments (2019) performed by both ensembles together. As stated in the program, “Cole’s work draws inspiration from personal stories gathered by the local LGBTQ+ community and explores the gender spectrum through visual art and projections integrated with musical creation.” The result is a six-movement choral work which employs the prerecorded and edited voices of various choral members, speaking on the role gender has played in their individual lives, as an introduction to each movement. The chorus’s function is very much akin to that of a Greek chorus, providing a moral, interpretive commentary on what is heard in the recording that introduces the movement. Here Cole showed a real talent for antiphonal and stirring, even Handelian, imitative contrapuntal writing. But the sound was extended by the composer through the addition of the sounds of the choir murmuring and chattering, creating a spectrum of voices. The most moving moment of the work in my opinion was at the great reprise of the opening line “Can you hear my voice? Let me have my harmony,” which is revamped into a refrain of the final movement:

I remember / Hear my voice / Hear my harmony

And at the final cadence the audience rose to its feet. In a remarkably eclectic night filled with fantastic choral singing and the most cutting-edge avant-garde music, perhaps the best measure of success resided in the fact that when the lights came up, we all felt as though we were part of the same community—a tremendous accomplishment in these times.

CD Review

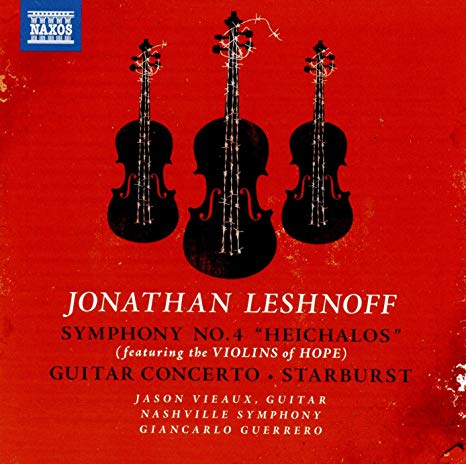

Jonathan Leshnoff: Symphony No. 4 “Heichalos”, Guitar Concerto, and Starburst by The Nashville Symphony Orchestra

This 2019 live recording release from Naxos presents Leshnoff’s Symphony No. 4 commissioned for the Nashville Symphony’s Violins of Hope project. The Violins of Hope are a collection of stringed instruments that were played by Jewish musicians during the Holocaust and have been restored and recorded on this album. The  composer believes his symphony represents a parallel to the Violins of Hope as an embodiment of Jewish survival. While the violins are a physical embodiment, Leshnoff’s music provides a more spiritual one. The subtitle, “Heichalos,” refers to an ancient text describing a way to achieve a divine communion through meditating oneself through “rooms” of deeper consciousness. In just two parts rather than traditional symphonic movements, Leshnoff intends for listeners to experience the musical depiction of each of these rooms. Bold chords set the tone for the beginning of Part I and the brass section is featured in the opening passages of thick orchestration. Although a dark overall mood is achieved, harp and woodwind help provide an ethereal characteristic to the heaviness of Part I shortly before a climactic ending.

composer believes his symphony represents a parallel to the Violins of Hope as an embodiment of Jewish survival. While the violins are a physical embodiment, Leshnoff’s music provides a more spiritual one. The subtitle, “Heichalos,” refers to an ancient text describing a way to achieve a divine communion through meditating oneself through “rooms” of deeper consciousness. In just two parts rather than traditional symphonic movements, Leshnoff intends for listeners to experience the musical depiction of each of these rooms. Bold chords set the tone for the beginning of Part I and the brass section is featured in the opening passages of thick orchestration. Although a dark overall mood is achieved, harp and woodwind help provide an ethereal characteristic to the heaviness of Part I shortly before a climactic ending.

The Violins of Hope feature in the contrasting Part II with long, lightly woven lines that Leshnoff gently incorporates with brass foundations and flute contributions. A sense of seriousness pervades the entire symphony and there is no doubt the musicians were committed to performing with sincerity, especially those using instruments from the collection. In the music score, the composer has inserted a question before Part II begins: “Who do you love?” and at the end, “Where are they now?” The reflective interpretation of the Nashville Symphony is made permanent on this recording, one that conductor Giancarlo Guerrero says the musicians are so honored to make.

Also on this album is renowned guitarist Jason Vieaux performing live Jonathan Leshnoff’s Guitar Concerto. The vibrant, three movement work proves no easy task for the

performer but Vieaux’s clarity is exceptional considering Leshnoff has written many bright runs in the upper register and descending arpeggio passages. The first movement is a fine movement to represent a modern guitar concerto while the Adagio and Finale movements implement the tried and true styles of guitar and orchestra writing. The Finale is definitely lively and full of dance-like spirit. Overall the orchestration is well-done and makes the concerto a decent addition to the repertoire.

Starburst is an eight minute, compact orchestral piece as exciting and stunning as its name. The strings race away from the start with rhythmic ferocity, punctuated by the timpani. At a climactic chord in the middle, every instrument falls away except the clarinet. It is left to float a long melody over the space that is suddenly created. Leshnoff says this moment in Starburst is one of his favorite places in his own music. A popular opening piece, the recording of Starburst by Nashville Symphony Orchestra will be the reference for future performances.

This stamp of ownership is something Guerrero is proud of and notes that the live recording of all three pieces benefited from the composer getting to work closely with the orchestra in many stages of rehearsals. The Nashville Symphony has established itself as a reliable group for producing quality classical recordings and that will make a lot of patrons in Music City very happy.

Nashville Opera’s The Cradle Will Rock: an Anthem for All of Us

Marc Blitzstein’s The Cradle Will Rock is an ode to the working class, consisting of bountiful hot-button social commentary and dashes of sly barbs to boot. The work takes place in “Steeltown, USA,” and follows union organizer Larry Foreman’s efforts to unite the workers of the town and to fight back against the all-powerful Mr. Mister, who is in control of every part of town life. No, this isn’t a politically incorrect off-Broadway production that premiered last year, but a 1930’s play in music that was famously shut down before it could even take the stage. And, strikingly, Nashville Opera’s production utilizes a combination of authentic acting, minimalistic set design, and stellar producing in a way that (combined with contemporary events) makes Blitzstein’s work just as relevant now as it was when he wrote it.

Cradle originally came about from the Federal Theater Project under the post-great depression Works Progress Administration – a seemingly forgotten time when the government deemed it important to fund many art programs during an economic downturn. Because of this context, it is important to note the situation in which the work “premiered,” as Nashville’s rendition pays courtesy to this touchy beginning.

The night that Cradle was to be performed, the theater abruptly shut down due to “budget constraints” – or perhaps due to the opera’s pro-union message. Moving to another theater twenty blocks north of downtown Manhattan, the performers had to sing from the audience to obey theater policies and Blitzstein had to scrap his orchestra ensemble and hastily play instead on a dingy upright piano. As such, it is notable that John Hoomes, Nashville Opera’s artistic director, chose to keep this sparse instrumentation and characteristically spare set design. Amy Tate Williams nails it on the jazzy piano accompaniment that blends effortlessly with the performers, and kudos to the surprisingly large, Nashville-based cast for their gripping acting which more-or-less pays homage to the actors and actresses that made the premiere possible.

While it takes the minimum to get this work right, it can be quite easy to get it wrong. Fortunately, the raw emotion from Nashville’s cast is one that draws the audience in and makes Cradle a success – switching from the court trial in night jail, to each character’s interesting backstory, the over-arching narrative is captivating despite its simplistic nature and less than stellar musical numbers. What makes it bearable, and sometimes beautiful, is the score, where spoof passages that taunt

the bad guys alternate with pointed, yearning arias that distinguish the others. (If it sounds like Leonard Bernstein, that’s because Bernstein was a Blitzstein protégé.) In both modes, the music is more expressive than the lyrics, which seem to have been written for a pamphlet.

Most of the story progresses as a merry-go-round of bribery and corruption. Before the audience can be awed by the riveting soliloquy of the union organizer Larry Foreman (Eric Pasto-Crosby), we have the anti-union Liberty Committee to indulge us. Led by Galen Fott as Mr. Mister, the cronies, all of whom bring a different air to their roles, are presented in vignettes of sorts while being blackmailed into agreement. All the while there is the bona fide Reverend Salvation (Brett Hetherington) who tailors his sermons to match the political imperatives of the time, while Editor Daily (Patrick Thomas), who’s “made to order” news (most of it fake), alters the rest of Steeltown’s thoughts over the course of the work.

There’s also the progression of the lap dog artists, Dauber (Darius Thomas) and Yasha (Scott Rice). Truly one of the most comical scenes, they cozy up to the coy Mrs. Mister (Martha Wilkinson). Through her vivid charm and flirtatious acting, she is able to lure the two once again into this promise of a financial safety net – as long as they join her and her husband in opposing the union. While the scene is innocent from the outset and perfectly executed by the actors, it is unnerving nonetheless as a situation that is still so prevalent in the arts today.

The performance’s best moments, though, is its honesty and moments which contain a hint of a kind of winking, motley spirit, as when Luke Harnish — who’s fun to watch throughout — executes a silly ballet as a macho football coach. Megan Murphy Chambers has a strong voice and a sharp, light appeal as Moll, though she must spend most of the play sitting and listening. Brooke Leigh Davis sounds full and resonant as Ella Hammer, who brings the show to what should be its emotional climax with “Joe Worker,” a memorandum of suffering anger in the face of oppression by the bosses.

While the work is more about meaning than musical richness, the story ends with a finale that brings all that came before it into one big anthem, exclaiming

“there’s a storm that’s going to last until

The final wind blows, and when the wind blows

The cradle” [that would be the cozy, lofty enclave of the one percent] “will rock!”

This is the first time the audience witnesses the full chorus, and the cast appropriately fills the hall of Noah Liff Opera Center with a heartening send-off.

Both an attack on wealth and the corruption it can bring, as well as a paean to labor and poor people struggling to get by, the political message of Cradle is just as relevant now as it was then, and its continued revival speaks to its potential to reflect on contemporary society. Nashville Opera brought all of this into focus by staying true to their motto: “Sing Bravely.” And while the conflicts between freedom and security, corruption and innocence, and power and integrity may have changed their manifestations since the 1930s, they still exist today and the continuing impact of The Cradle Will Rock can be found in its ability to speak plainly to these issues through music.

Spano and Trpčeski with the Nashville Symphony

On the first weekend in May the Nashville Symphony gave a concert featuring Michael Gandolfi’s The Garden of the Senses Suites, Jean Sibelius’s Symphony No. 5 in E-Flat Major, Op. 82 and Sergei Rachmaninoff’s epic Concerto No. 3 in D Minor for Piano and Orchestra with Simon Trpčeski on piano and Robert Spano at the podium. The evening was mixed, but ended wonderfully.

The concert opened with Gandolfi’s Suite. Written on a commission by guest conductor Robert Spano, the piece is one of a series titled the Garden of Cosmic Speculation and was inspired by Charles Alexander Jencks’s Garden of Cosmic Speculation, and actual garden outside Dumfries, Scotland which, “celebrates nature and his [Jencks’s] own fascination with advances in cosmology, genetics, chaos theory, fractals and other areas of contemporary science.” One of thirteen movements in the composition, the suite is organized along the lines of one of Johann Sebastian Bach’s suites with each movement corresponding to a dance movement. Further, each movement is meant to also correspond in a synesthetic gesture to one of the other senses: Allemande (Audition), Courante (olfaction), Sarabande (gustation), Passepied (palpation), Gigue (vision), and Chorale (the sixth sense: intuition).

Obviously, there is an awful lot going on here to digest in one hearing, but ignoring all of this and just paying attention to Spano’s realization of Gandoli’s genius for style and instrumentation was quite rewarding. The waves of chromaticism in the dignified first movement, and the sparkling pizzicato strings in the Passepied were remarkable. My favorite was the last movement, a setting of Bach’s chorale “O wie selig seid ihr doch, ihr Frommen” set in a rhythmic and registrational self-reflexive commentary in which, as Gandolfi described it, the “…music anticipates or in

tuits itself.” Spano’s interpretation showed his knowledge of the piece and his talent for interpreting contemporary American music.

Maestro Spano is a world-class conductor and has done amazing things with the Atlanta Symphony in his two-decade tenure there. After winning six Grammys and surviving a dreadful lockout in 2014, he has certainly earned the esteem he

has garnered and when he begins his new position in Fort Worth in 2021 there is a lot of appropriate optimism. However, his approach with the baton is remarkably different from our own Maestro Guerrero, a difference that might be exaggerated in comparing the reserve of Richard Strauss to the vigor of Georg Solti, and this difference came through in the Sibelius.

Jean Sibelius began work on his Fifth Symphony in 1915 and it underwent a number of revisions before achieving its final form in 1919. It features a highly developed organicism that rests on the slow emergence and dénouement of the famous “swan theme” in the primary climax of final movement, presented by the horns. The piece as often been described as “regressive” from a formal and harmonic point of view, but this accessibility can conceal a remarkably intuitive formal organization. On Friday there were marvelous moments, in the Andante in particular where Nashville’s woodwinds deserve special mention, but the grand sweep of Sibelius’s piece felt off balance, the famous final chords more perfunctory than transcendent.

The epic work depicted in the movie Shine, a docudrama of child prodigy David Helfgott’s troubled career, Rachmaninoff’s Third Concerto is often described as the most difficult piece in the concert repertoire of the piano. However, after intermission when Simon Trpčeski breezily strolled on stage to present it, his confidence was infectious. Beginning the

famous first theme with a marvelous singing tone and constantly attentive to Spano and the orchestra, by the arrival of the second theme, Trpčeski seemed to bring orchestra, conductor and himself into alignment for an extraordinary and explosive performance.

He took to the powerful cadenza, playing the earlier and longer version, with a certain joy, stretching his legs out beneath the piano as the entire stage seemed to move as one. The intermezzo and final movement were equally great to the first, with the maze of themes in Rachmaninoff’s final movement articulated as though it was a walk through an (astoundingly) beautiful park. At the final cadence the audience leapt to its feet and would not calm until treated to an encore—which Trpčeski obliged. (I hear he did on Saturday too). The Classical Series continues on May 17th with Thibaudet Plays Turangalîla, a rarely heard masterpiece by Olivier Messiaen featuring the otherworldly, electronic ondes-Martenot.