the Nashville Symphony

Handel’s Messiah at the Schermerhorn

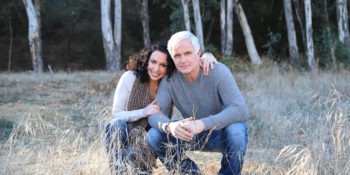

On December 19-22 the Nashville Symphony gave its annual production of Georg Frederic Handel’s Messiah at the Schermerhorn Symphony Hall, featuring soprano Mary Wilson, mezzo soprano Elizabeth Batton, tenor Garrett Sorenson, and bass Andrew Foster-Williams. This holiday tradition, which seems to extend all the way back to 1963 in Nashville when Willis Page directed it on December 15th, is proving to be one of the highlights of the holiday season in Music City.

Oddly enough, however, in 1742 when Handel wrote his masterpiece oratorio, it was not designed to be performed during the Christmas season but rather during Lent as a more restrained and religious entertainment than Handel’s secular operas which along with their competition where flooding the London market. Thus, the oratorio in general lacked the scenery and staging of traditional opera and emphasized a sacred rather than a secular topic. Handel more than made up for this in his musical setting, especially in the

recitatives, which span a continuum from the reduced “secco” instrumentation of voice and keyboard to the fully accompanied recitatives in which the vocal line is inlayed within the full orchestra’s texture. Maestro Guerrero’s handling of these recitatives was quite remarkable from the very opening number, “Comfort Ye, My People” as sung by Sorenson.

We last heard tenor Garrett Sorenson last month in the Symphony’s production of Rachmaninoff’s The Bells. With a strong and well-polished instrument, Sorenson leant a warmth to Handel’s ornamented melodic line. In “Every Valley Shall Be Exalted” the text painting came across as sincere and without contrivance, a great achievement in so well know a work as this. Similarly, Foster-Williams’ bass brought new life to his line and coupled it with a supple tone that drew on a remarkable clarity in diction, his interpretation of “The People that Walked in Darkness” was terrifying and yet expressed the inlaid hope for redemption.

Mezzo-Soprano Elizabeth Batton was refreshing in her interpretation, and her voice blended exceptionally well with Sorenson’s (Batton’s husband) in the second of the work’s two duets “O Death, Where Is Thy Sting.” Another magnificent moment was Soprano Mary Wilson’s performance in the delightful shift from secco recitative to the accompanied (“And the Angel Said unto Them” followed by “And Suddenly there Was with the Angel”) that opens the second half of Part One. She created a nuanced dramatic shift that articulated her character’s awareness behind the words she was singing as though her recognition of the “heav’nly host” emerged slowly in its presence-a moment well-articulated by Maestro Guerrero’s delicate direction.

However, the star of the performance, as it should be, was Tucker Biddlecombe’s marvelously well-prepared Nashville Symphony Chorus. Their diction, balance and intonation were remarkable, particularly in the Hallelujah anthem and fuguing chorus as well as the remarkable “Amen” chorus that ended the piece. Special mention goes to Nashville’s amazing strings led by Jun Iwasaki and the two trumpets that announce the Hallelujah chorus, they managed, with Handel’s reduced orchestra, to fill the magnificent Schemerhorn Hall with music—a great challenge with concerts such as these. In all the evening was a refreshing performance of the canon’s oldest chestnut—a marvelous holiday gift for the Music City!

the Nashville Symphony

“Neglected Jewels” and “Pristine Acoustics:” Paul Jacobs Returns to Nashville

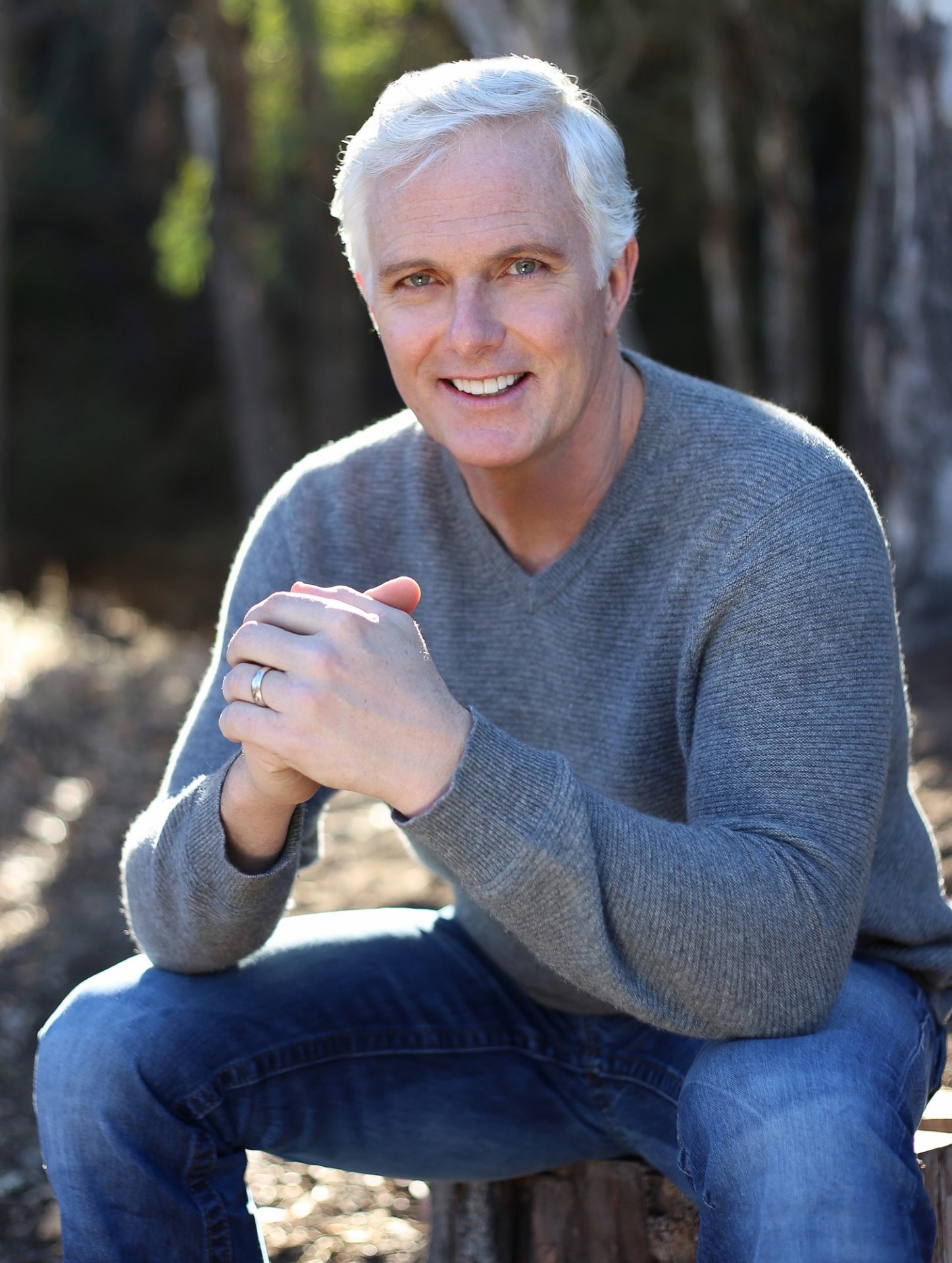

Ahead of his visit to Nashville on November 21-23, when he will play Horatio Parker’s Concerto in E-flat Minor for Organ and Orchestra, Op. 55 in concert with the Nashville Symphony, we had the opportunity to ask virtuoso organist and Grammy winner Paul Jacobs about the piece, performing at the Schermerhorn with the Nashville Symphony and about his instrument.

Ahead of his visit to Nashville on November 21-23, when he will play Horatio Parker’s Concerto in E-flat Minor for Organ and Orchestra, Op. 55 in concert with the Nashville Symphony, we had the opportunity to ask virtuoso organist and Grammy winner Paul Jacobs about the piece, performing at the Schermerhorn with the Nashville Symphony and about his instrument.

MCR: We are quite excited for you to come visit Music City to play with the Nashville Symphony! Could you tell us something about how the project got started?

PJ: It’s been a tremendous pleasure to have worked with Giancarlo Guerrero on several occasions, most recently with the Cleveland Orchestra, when he suggested it might be exciting to record a program of American organ concerti in Nashville. Given the abundance of repertoire for organ and orchestra (much more than people realize), it wasn’t difficult to identify some marvelous works that deserve to be heard by audiences and recorded for posterity.

MCR: What can you tell us about Horatio Parker’s Organ Concerto? Are there highlights in particular that we should listen for?

PJ: Horatio Parker’s organ concerto is a neglected jewel, a work of striking craftsmanship and deep feeling. Parker was an important American composer of the late-19th century, part of a group known as the “Second New England School”, whose music was strongly influenced by the German tradition. Warmly Romantic in style, this concerto tears at one’s heartstrings. A soaring melody is heard in the opening bars of the music, carrying the listener into an alluring yet wistful landscape. The first movement concludes with a dialogue among organ, violin, horn, and harp–pure gold. The Scherzo-like second movement provides a touch of effervescence, levity, and wit. The full glory of the organist is made manifest in the final movement, replete with virtuosic pedal writing and a dramatic cadenza. It’s thrilling to play, believe me!

MCR: You have performed in Nashville before, indeed in 2017 your world premiere of the revised version of Michael Daugherty’s Once Upon a Castle for Organ as performed with the Nashville Symphony and Maestro Guerrero (on Naxos) won a Grammy Award. What is it like to play with Guerrero, the Nashville Symphony and on our Martin Foundation Concert Organ?

PJ: I’ve only the highest admiration for Giancarlo Guerrero, a consummate artist. He leaves no stones unturned, and his intelligence and passion are inspiring, on the podium and off. It’s an honor to join him and the Nashville Symphony–a stellar orchestra in every respect. Given all the musicians involved, the Schermerhorn’s pristine acoustics and world-class pipe organ–all the stars should be in alignment for this special project!

MCR: As chair of Juilliard’s organ department, a touring virtuoso, and champion of not only the canonical repertoire but also of contemporary music for the instrument–solo and collaborative–what would you say is the state of the organ in the classical world?

PJ: Though the organ has been on the periphery of classical music for quite some time, I’ve dedicated my life to doing all that I can to bridge this gap. This is due to a host of complex reasons that could fill a book (which I might write one day), but suffice to say the glory of the instrument continues to shine brightly through performances in every corner of the world, with audiences eager to listen. Once a New York Times critic told me that, in his experience, the two most devoted groups of music lovers where opera buffs and organ fans. Many in the classical music establishment seem unaware of the widespread devotion and support the King of Instruments actually has.

MCR: What other instruments do you play? Do they inform your interpretations at the organ?

PJ: The piano was my first instrument, which I began studying seriously at an early age and continue to play almost daily, though not in public. As an undergraduate student, I frequently played harpsichord, primarily for the opportunity to play chamber music. Making music with others has always been important to me–something not often expected of organists. And, yes, playing one keyboard instrument inevitably informs (and sometimes transforms) another, expanding one’s concept of musical expression.

MCR: Your marathon performances of the complete organ works of J.S. Bach and Olivier Messiaen have given you a legendary status in the classical music world. You also made history by becoming the first organist to receive a Grammy Award for a solo recording of Messiaen’s Livre du Saint Sacrement. Personally, do you have a favorite performance of your own?

PJ: This may be impossible to answer, given the ephemeral nature of live performance. But there are also too many happy experiences to recall, fortunately! I will say that some of the most meaningful encounters I’ve had have been with audiences in smaller communities and in more intimate settings. People crave beauty, wherever in the world they happen to live.

MCR: After Nashville and this recording, what’s next?

In addition to upcoming solo recitals, later this season I’ll be joining Giancarlo in Europe for performances of a concerto by the late Stephen Paulus. Also, the Daugherty that we recorded in Nashville I’ll be playing with the Philadelphia Orchestra in February (having just performed it with the Kansas City Symphony last month). Then I’ll be joining the Utah Symphony for a Handel organ concerto and Samuel Barber’s Toccata Festiva, which I recorded last season with the Lucerne Symphony in Switzerland. Finally, I’m anticipating the release of a recording made with the Cleveland Orchestra of a riveting organ concerto, Okeanos, by contemporary Austrian composer Bernd Richard Deutsch.

Horror in Music City:

An Evening of Superior Cinematic Wonderment: Manual Cinema’s Frankenstein

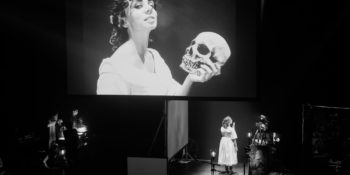

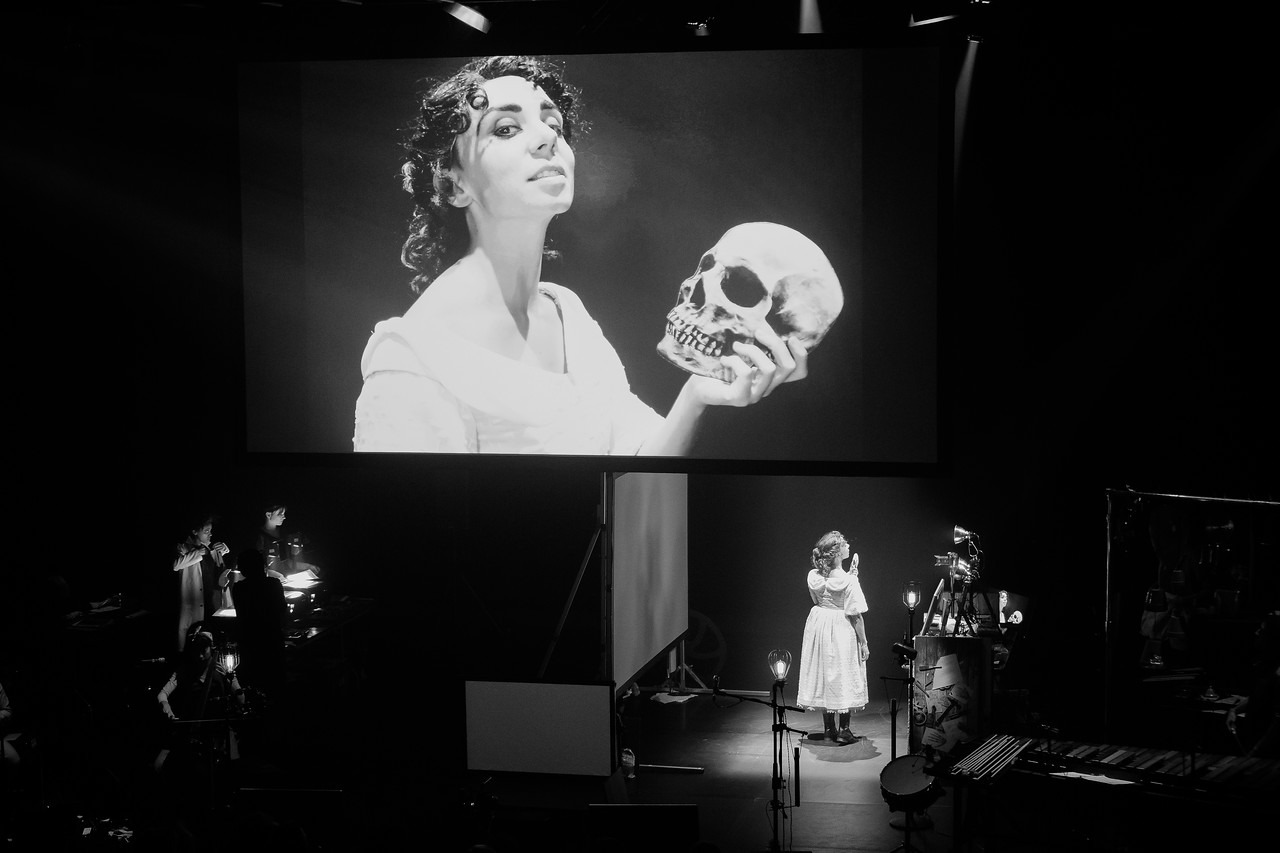

Upon setting foot in the large black-box theater of OZ Arts Nashville and rounding the corner of a towering construction holding hundreds of stadium style chairs, it was evident I was in for a rare theatrical experience. 25 minutes to show time and the house was already packed, people steadily trickling in with entertained expressions as they were forced to wind through the mass of artsy haircuts, funky glasses, and Nashville chic to find a seat. Artistic Director of OZ Arts Nashville provided the following context for Manual Cinema’s uncharted theatrical territory ahead: “While they may use sophisticated life-feed video techniques, and even robotic percussion instruments, much of their aesthetic is inspired by old technology, including overhead projectors, which they use to create magical effects. Cardboard cut-out shadow puppets cast emotionally-stirring silhouettes, and old-school hand animation techniques evoke phantasmagorical locations, from mountain-tops to spooky gothic mansions.”

“…double shot of imagination, a dash of genius, a sprig of vintage, and a whole lot of finesse.”

Palpable curiosity buzzed through the room as the audience admired the curtain-less stage filled with projectors, screens, cameras, instruments hanging in mid-air, costumes, props, wigs, and a variety of

unrecognizable items. Hanging above the set was an oversized cinema screen, floating just above height level of anyone walking underneath. Actors, puppeteers, and musicians came and went freely from the stage prior to the show, unconcerned about mystery or secrecy, going about their preparations routinely. Once the entertaining task of locating an empty seat for each guest of the sold-out opening night was complete, the lights dimmed and the audience braced itself for the unexpected. What followed was one of the most enchanting, captivating, and exquisitely executed pieces of theatrical art I have ever experienced.

My eyes immediately drawn to the large cinema screen, the film began with silhouette-style paper puppetry representing characters and objects. Special effects with lighting, live instruments, and electronic sounds accented the film at poignant times, creating musical motifs for characters, emotions, and events. A charming and occasionally startling rendition of Mary Shelley’s life unfolded, and I felt myself drawn in by the eerie combination of music, puppetry and magic holding it all together. The scope of sound and music created to attend the film were so impeccably chosen and timed, I hardly remembered there were live musicians at all. The instrumentalists wove together a lush tapestry of effects, timbres, melodies, noise, and rhythmic impulses, creating an affecting ambiance that hooked me, manipulating my emotions moment by moment.

Although I could hardly tear my eyes from the screen, the temptation to witness the remarkable things going on below was strong. After all, Manual Cinema both purposefully and ingeniously creates an environment in which the audience is invited into the production process, encouraged to observe the synthesis, and welcomed into the tangible world of the film’s engineering. On stage, the creators were manipulating paper silhouettes on several projectors, moving seamlessly and unbelievably quickly from one projector to another, casting ominously beautiful scenes onto a large facing screen mirrored by the cinema screen hanging above. Upon looking back to the cinema screen for the full visual experience, to my astonishment one paper cut-out began to move in an incredibly life-like manner. I looked to the puppeteers in an attempt to decipher how they might be creating this effect, only to find a live actress now in front of the shadow screen, having taken the place of the silhouette cut-out. The transition was absolutely imperceptible. The film continued to develop in similarly extraordinary ways as they utilized an extensive array of unique techniques.

After illustrating heart-breaking misfortune in Shelley’s life with the loss of her infant child, the film took a darker path, depicting her visit to Lord Byron and a new-found determination to write a “ghost story.” As the film evolved into a transformative re-telling of Shelley’s Frankenstein, black and white video was introduced and used in uncommon ways throughout the remainder of the film. Puppeteers who previously manipulated paper, props, or their own bodies in front of a shadow screen, were now on camera as entirely different characters. The frequent transitions from projector to shadow screen to camera continued in a seamless fashion, but the audience had now become wholly and blissfully aware of the incredible detail required to make this cinematic wizardry happen. Actors and puppeteers were running in and out of shots, manipulating props, operating cameras, ducking, rolling, crawling, and quick-changing around, under, and through each part of the stage, creating an astonishing illusion.

As the story unveiled Victor Frankenstein’s woefully created creature, 3D puppetry was introduced with HD video in color. The addition of hi-res video at this time was remarkably moving, depicting the creature’s initial perspective of the world and their own horrific body in this unknown place. The heart-wrenching tale of the creature’s struggle to understand the world, love, and loss ensued, shifting between all forms of media as the story progressed. As the somber, wordless narrative drew to a close, Mary Shelley’s character was drawn back into the film, tying the pieces of her life, work, and adversity together into one melancholic, magnificent bow.

Co-Artistic Director and puppeteer Sarah Fornace was remarkable in her stunning portrayal of Shelley’s fragility and strength, and analogously brilliant depiction of Victor Frankenstein’s deranged passion. Puppeteer Leah Casey’s portrait of Percy Shelley was the perfect complement to Fornace’s Mary, not to mention her beautifully etherical vocals in conjunction with the film’s chamber musicians. Kara Davidson’s dark and tender interpretation of The Creature contributed depth and sensitivity, in addition to her light and flighty moments as Elizabeth Frankenstein. Sara Sawicki and Myra Su contributed their personal brilliance as Lord Byron and puppeteer extraordinaire, respectively.

Musicians Peter Ferry (percussion), Lia Kohl (cello, aux percussion, vocals), Rachael Dobosz (flutes, aux

percussion, piano), and Michael Chen (clarinets, aux percussion) brought the film to life with explicitly executed chamber music, contributing to the theatricality of the work both in costume and interaction with the cast. Cellist Lia Kohl shared, “Some of the music is a little bit improvised, so there’s definitely some artistic input of ours. A lot of the cues are visual. I like to compare it to ballet or opera, something that’s a little bit more responsive. It’s definitely chamber music.”

Percussionist Peter Ferry spoke about his contribution to composers Ben Kauffman and Kyle Vegter’s music-writing process: “As a habit, I just accumulate cool sounding junk. That is a sink—it’s everything in the kitchen sink here—some flower pots, which you just find, but they kind of accidentally have different pitches. I’ve got different gongs, [a] cooking pot, pipes that are cut to different lengths to be pitches, other pipes that are found. A piece of a car, it might be a hubcap, used kind of like a metal guiro. We were going for a mad laboratory feeling, both in the sort of sounds that are included, but also in the sculpture that it creates. The composers have just a total ‘game for anything’ sort of approach. They visited my studio, and we went through every single item and recorded everything. As they started to work on the composition, they would take the sound samples of different things and say ‘OK, I really want to use this, I really want to use that.’ As they started to share drafts with me, we would then kind of edit and revise together, simultaneously thinking about how is it going to be laid out. When you’re working with a percussionist, that’s a necessity.”

Manual Cinema’s Frankenstein is a tall glass of nouveau with a double shot of imagination, a dash of genius, a sprig of vintage, and a whole lot of finesse. How refreshing to attend a classic work of literature reinvented with such collective passion, ingenuity, and class. I’ll certainly be looking forward to the next opportunity I have to see this performance collective’s innovative genius.

At TPAC

‘Once on this Island’ Opens its U.S. Tour in Nashville

A bustling stage and charged audience await the opening night of the National Broadway Tour for Once on This Island. Originally designed and performed “in the round”, the show accommodates that same intimacy by seating audience members within Dane Laffrey’s elaborate set design. The primary staging area is front and center, and there are several inlets on either side, as well as two elevated platforms that house the musicians. Though crude and colorful, the set easily morphs to whatever environment is required- for the beginning, the setting is a contemporary dwelling on an island in the French Antilles. Corrugated metal panels and stained fabrics adorn the different levels of the set pieces. Audience members are led onto the stage to take their places in the ambience as the cast members interact with one another. After an amusing bit featuring the phone of an “audience member” meant to deter the use of electronic devices during the show, the lights dim and the players begin.

Rosa Guy’s novel My Love, My Love: Or, the Peasant Girl, the source material from which this show was adapted, tells the story of a young girl named Ti Moune who falls in love with a man of a higher class than she as she nurses him back to health from an accident. Though the characters and circumstances differ from the novel to the musical, the general sentiment remains the same. Once on This Island features a beautiful and spirited young woman, seemingly protected by the Gods, who feels she is destined for a story larger than the one of her home. In a world rife with natural disaster and tragedy, director Michael Arden finds it important to

point out that “no place or person is immune to the power and wrath of the gods.” Thus, our heroine’s lovelorn end is both bittersweet and jubilant, celebrating the cyclic nature of life and the power of one ray of hope to survive even in the greatest darkness.

Courtnee Carter portrays Ti Moune with such earthen grace and enthusiasm, not to mention her powerful vocal range and ability. Even in her exposition, the agility of her voice in transferring from a belting chest voice to a tender and fragile timbre is striking. Ti Moune is both headstrong and devoted, and Carter navigates her character expertly in the way she sings and moves. MiMi Crossland melts hearts as Ti Moune’s younger self and real-life counterpart with a voice that soars confidently through the din of adult voices. Her on-stage quick change from the school-child uniform to the signature red dress of Ti Moune is exquisitely executed with the help of fantastic lighting and an ever-moving ensemble. No member of the cast is less than superb. Jahmaul Bakare, Kyle Ramar Freeman, Tamyra Gray, and Cassondra James shine as both storytellers and Gods: Bakare’s Agwe is mighty, Gray’s Pape Ge maliciously enthralling, and James’ Erzulie elegant and nurturing. Freeman captivates as Asaka, with demonstrative vocals that are nothing short of impressive. Philip Boykin’s deep and hearty voice warms the Tonton Julian, a complement to the caring and maternal Danielle Lee Greaves (Mama Euralie), and it proves difficult to not fall for Tyler Hardwick’s Daniel right along with Ti Moune. The ensemble bewitches as they seamlessly weave between being storytellers to set pieces to supporting roles.

Despite an incredible overall performance level, several moments of the show stand out in terms of general effect. The marriage of lighting and staging come together so harmoniously in the initial storm that one could forget the reality of being surrounded by four walls and a ceiling in a theater. Similarly, the car ride and consecutive car crash are electrifying to behold. When the ensemble forms the simulated car and Hardwick mimes the effect of a bumpy road, the cast members make believing the pantomime easy for the audience with skillful delivery and precise timing. The crash itself is jarring as Daniel is ejected from the vehicle amidst the thunder and rain. Another moment of note is the tale of the Beauxhommes via the shadow show behind the storytellers. The ability to emote and communicate through posture and movement alone is remarkable, and each cast member involved performs exceptionally.

Finally, possibly serving as the most important moment of the show is Ti Moune’s dance at the ball. Not only rich in color and imagery, the scene is solidified by the entrancing choreography that serves specifically to each character that joins the dance. Ti Moune’s radiance sparks inspiration in one dancer at a time, breaking barriers of class and skin color until finally reaching the puzzling Daniel. It is a moment full of love and irony, but this moment unfortunately also serves as the first whiff of Ti Moune’s heartbreaking downfall. By this point in the show, the costuming has transformed several times, from contemporary fashion to embellished civilian costuming of the Gods, and then to formal attire of centuries past. Integral and integrated, the costumes are indicative of each character’s attributes from one setting to another.

Unity is the primary theme of the musical, both in production and message. On the surface level, the plot revolves around the story of a young girl attempting to unite two different groups of people. However, beneath the surface, the plot also stresses the integration of the spiritual world with terrestrial events. Cassondra James’ flute interlude is an excellent example of this theme, as she, the God Erzulie, responds to the vocalists within the instrumental accompaniment of “Ti Moune.” Though subtle, this gesture is powerful in reinforcing the role of the Gods in Ti Moune’s journey. Even beyond this moment, the instrumentalists’ execution of Stephen Flaherty’s score is both supportive and evocative, with the use of unconventional sounds to represent the supernatural and a variety of musical styles intensifying the idea of a story weaving throughout time.

…an absolute masterclass in integration, with flawless storytelling enhanced by brilliant costuming and lighting.

Once on This Island is an absolute masterclass in integration, with flawless storytelling enhanced by brilliant costuming and lighting. Exhibiting an excellent cast and wonderful staging, the one act passes in a flash, reiterating the idea that stories and culture go hand in hand, and that the story being told is not only timeless, but perhaps even more important- timely.

This production of Once on This Island will continue in Nashville through October 20th. Tickets are available at TPAC.org For more information, visit onceonthisisland.com, or find the show on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.

Nashville Opera’s Madama Butterfly

On October 10, Nashville Opera opened its 2019 season with a delightful production of Giacomo Puccini’s Madama Butterfly at the Andrew Jackson Hall in the Tennessee Performing Arts Center. The production, starring the Cuban American lyric soprano Elizabeth Caballero, was remarkable for the exquisite vocal performances as well as its heart-rending telling of Puccini’s tragic tale.

Completed in 1904, Madama Butterfly, like most of Puccini’s works, rests uncomfortably somewhere between the long evolution of Italian opera and an expression of the verismo movement of the time. First a movement in literature and then in opera, a verismo narrative is characterized by a naturalistic setting in which a poor or common character is driven to a catastrophic end by, as W.H. Auden once put it, “…an impersonal natural need outside his control.” These impersonal, natural needs are typically social constructs of religious and/or societal norms.

In Madama Butterfly, the expectations of marriage and family are the societal norms that drive Puccini’s exotic heroine, Cio-Cio San (aka Butterfly) to marry Lieutenant Pinkerton, and to wait for him when all others have given up hope for his return. It is Pinkerton’s undermining of these expectations that ultimately lead to her suicide. However, Cio-Cio San is not a common woman. Born wealthy, she is not forced to make immoral decisions due to these impersonal needs; rather, she is able to make markedly moral decisions despite those needs. A woman with an undying faith is a stereotype in Romantic opera, one thinks of Agathe (Der Freishcütz), Senta (Der Fliegende Holländer) or Desdemonda (Otello) and in this way she is almost a typical opera heroine set within a tragic verismo context.

Caballero, with her grace, charismatic presence, stamina and wondrous instrument, is cast perfectly as Butterfly. Indeed, she thrives in Puccini’s relentless setting. From her entrance aria early in the first act, where she is brought to the very top of the soprano range, until the very end, Caballero’s intensity and presence was remarkable. Her central aria, “Un bel dì vedremo,” was simply astonishing, her delicate voice’s gentle timbre clearly articulating Butterfly’s hopeless optimism.

Maestro Dean Williamson and the Nashville Opera Orchestra deserve mention here for their subtle handling of Puccini’s motivically organized opera. Apart from the “Un bel dì” motive, which is overtly reprised at Pinkerton’s return, Puccini’s motivic designs are less directly referential than his earlier works, with some creating more of a musical atmosphere and ambiance. Williamson handled this subtle design with great care, all the while maintaining the incredibly important balance in Puccini’s Orchestra—the heavy orchestral brass accompanying the “heroic” Pinkerton versus the lighter and more delicate presence of Butterfly.

For his part, Adam Diegel played a dashing Pinkerton, with a bright and polished tenor that made his naïve seduction of Butterfly quite believable. His and Cabllero’s voices blended with a surprisingly poignant intimacy at the end of the first act in their duet “Viene la sera.” Pam Lisenby’s costuming was simple but elegant–Pinkerton appears in the first act in a heroic white uniform but returns in a dreaded black uniform. The straight and square lines of his uniform contrasted powerfully with the flowing curves and colorful prints of Butterfly’s kimonos.

Sharpless, the American Consul, is one of the most innovative of Puccini’s narrative characters. This baritone part, a voice type traditionally reserved for the antagonist, here plays the role of a Greek chorus, warning Pinkerton (and the audience) of the approaching catastrophe and commenting on it afterwards. As Sharpless, on Thursday Lester Lynch seemed to have some difficulties in terms of power in the first act, but by the second his voice bloomed into a well-rounded sound that carried throughout TPAC’s very difficult hall. His acting was delightful, at times humorous and at others reprimanding.

If Sharpton communicated the wrongs in Pinkerton’s seduction, Suziki, played by the wonderful Cassandra Zoe Velasco, expressed the pain that it inflicted on Butterfly. At the end of the second act, her flower duet with Butterfly was delightful when their voices gently blended in a magical moment as cherry blossoms floated down from above.

Joel Sorensen, as the marriage broker Goro, was pretty darn funny, as was Brent Hetherington as Prince Yamadori (Hetherington doubled well as “The Bonze”). The blocking of the production was genius with Kate Pinkerton (Sara Krigger) innocently invading Butterfly’s space and privacy; an encroachment on Butterfly’s world that served as an immediate and symbolic expression of Western imperialism’s influence on the East.

In all Director John Hoomes has pulled off another success and it bodes quite well for a fun season of Nashville Opera, which will return in December with a production of Gian Carlo Menotti’s holiday opera Amahl and the Night Visitors.