At the Schermerhorn

Salute to Vienna: A New Tradition for Music City’s New Year

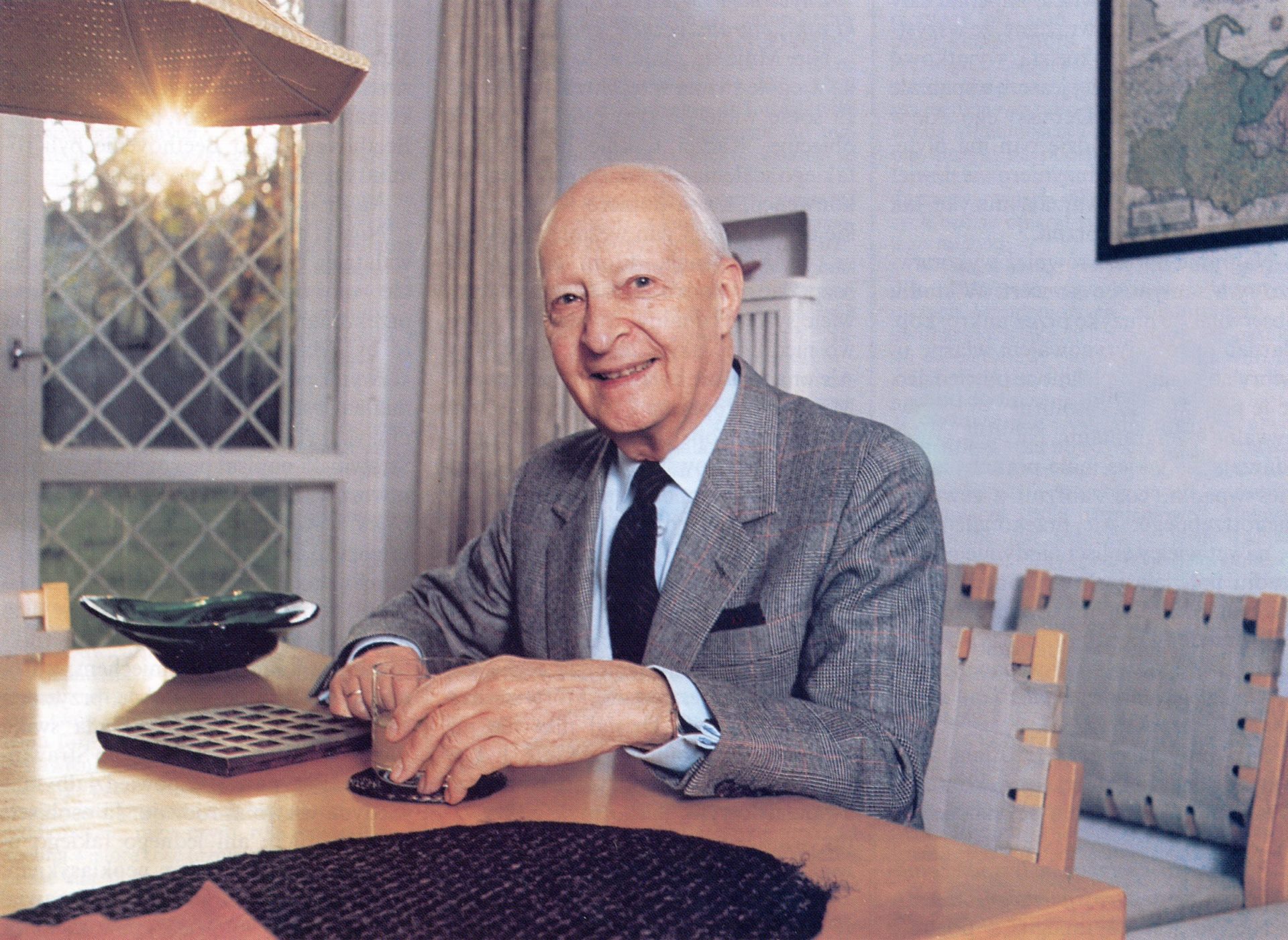

On January 3rd at the Schermerhorn Symphony Hall, Nashville was treated to a glitzy, glamorous, and grand celebration of the New Year–Viennese style. With this concert, Nashville joins an eight decade tradition that began in Vienna and over the last twenty-five years has found its place in cultural centers all across North America, including New York, Boston, Chicago and Los Angeles. The evening featured Conductor/goofball Bernhard Schneider leading the Strauss Symphony of America as well as the National Ballet of Hungary, four International Champion Ballroom Dancers, Viennese soprano Jennifer Davison, and New York tenor Brian Cheney in an event that was both family friendly and fun.

As is appropriate, the program was dominated by waltzes, and polkas, wonderfully imagined by choreographers Marianna Venekei (Ballet) and Csaba László (Ballroom) in which skirts twirled and whooshed. Cheney sang in fine voice, one could tell that the numbers were set comfortably within his glowing, classic instrument and that he has sung these songs before. Indeed, on his Facebook, he estimates that in the last eight years that he has performed in these productions he has sung for around 50,000 people! Davison also sang very well, with a warmth and luxurious instrument that blended well with Cheney’s luster.

Maestro Schneider, between cheesy “Dad-jokes” led the Symphony through decent renditions of the dances; his interpretation of Josef Strauss’ Mein Lebenslauf ist Lieb und Lust was delightful and that of Johann Strauss Jr’s Leichtes Blut hellishly fast. The nostalgia in “Hör’ ich Zimbalklänge” was aching, as he invited the audience to hum along with Davison’s song. Perhaps the best part overall was the encore, begun with the Blue Danube Waltz and ended with a sing-along to Burns’ classic “Auld Lang Syne” (with the music printed at the back of the program just in case). Overall, I enjoy the New Year and I like to celebrate it, but I’m not too interested to brave the cold to see a note drop, with Salute to Vienna, the Music City has a new New Year’s tradition.

Oz Arts Presents

Local Artists in “The Longest Night”

On December 20th and 21st Oz Arts Nashville presented The Longest Night, an interdisciplinary collaboration celebrating the winter solstice, and the next installment of their season’s eight different projects spearheaded by Nashville-based artists. It was an all-inclusive celebration in song, dance, improvisation and spoken word with some of Nashville’s most creative minds.

Overall the two-act performance was organized around a narrative of birds surviving the longest night as drawn from the poetry of Wendell Berry, especially his To Know the Dark:

To go in the dark with a light is to know the light.

To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight,

and find that the dark, too, blooms and sings,

and is traveled by dark feet and dark wings.

From these lines Director Jason Shelton created an exploration of this idea that privileges the darkness as a creative force, an idea which played the ruling narrative of the production.

The evening opened with Ryoko Suzuki performing a meditative and self-reflective prelude on a harmonium

soon joined by the ensemble in a performance of Berry’s poetry. Then world jazz vocalist Marcela Pinilla came

onstage to perform “Oscuridad.” In the second act she also sang “Farolito,” (“festival light”) with a remarkable charisma that warmed the room in an extroverted performance that balanced nicely with Suziki’s introspection, particularly in the latter’s performance of the “ancient and mystical” mantra “Om Namah Shiviaya.”

Then the Portara Ensemble performed, “Kalado” a Latgallian winter solstice folksong, the first of three arrangements they would perform that evening. Of these, Patrick Dunnevant’s arrangement of Stille Nacht was my personal favorite, playing as it did to the ensemble’s

strengths in timbre and texture with a harmonic language that seemed to lie somewhere between Copland’s pandiatonicism and Hindemith’s stacked perfections. (Much of the performance is available on Portara’s new release, here)

Virtuoso bassist Victor Wooten performed a solo arrangement of “The Christmas Song” rich in extended tapping techniques and a jazz flavored romantic nostalgia and his brother Roy “Futureman” Wooten led a rhythmic but free improvisation with Jeff Coffin and Ramakrishnan Kumaran. This jazz inspired celebration continued deep into the second act with Jeff Coffin’s “As Light Through the Leaves” featuring solos by Coffin on Flute and Pat Coil on piano. Soon, too soon, the concert came to an end with the uplifting “And All the Earth Shall Sing,” during which the audience was invited onstage for a dance party.

Depicting what I believe were the birds exploring the night, the Epiphany Dance* Partners, ingeniously choreographed by Lisa Valeri Spradley, were a constant presence onstage and throughout the performance.

Their role in the production was interesting and quite autonomous; they could interpret the music, or ignore it, or just sit down and watch the performance with us. Their dance could create a simple distraction, or become quite poignant as it did during Roxanne Crew’s dance to “Oscuridad” and Allison Hardee’s dance to the Futureman’s “Improvisation.”

Across the evening, Poet Ciona Rouse’s reading (she has a marvelous voice) assisted in unifying the evening with richly-told “Narratives.” Rabbi Rami Shapiro’s Story “If Not Higher” was funny and quite intimate.

At the end, I remembered being quite excited by Director Jason Shelton imploring the audience to participate in the performance. In a country so fraught with division as ours currently is, I was excited for a concert that emphasized diversity in content and inclusivity in performance, especially with the opportunity to sing with those around me and those onstage. Unfortunately, all we could join in with were the chants and with Peter Yarrow’s festive “Light One Candle.” My only wish was that there were more opportunities for this, perhaps we might all have sung a carol or two together? In any case it was a wonderful holiday and perhaps my favorite holiday concert event of the year—I hope to see it again next year!

the Nashville Symphony

Handel’s Messiah at the Schermerhorn

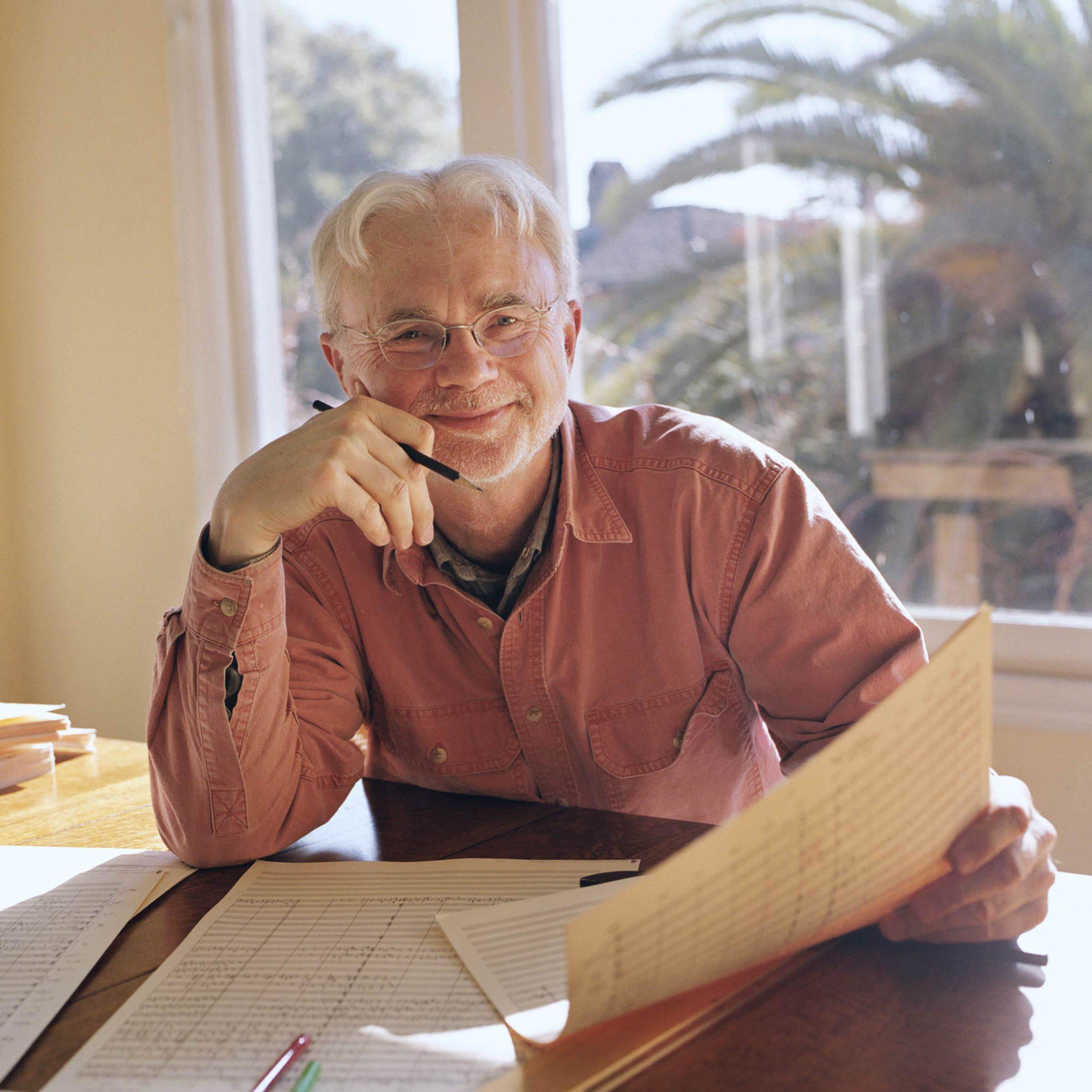

On December 19-22 the Nashville Symphony gave its annual production of Georg Frederic Handel’s Messiah at the Schermerhorn Symphony Hall, featuring soprano Mary Wilson, mezzo soprano Elizabeth Batton, tenor Garrett Sorenson, and bass Andrew Foster-Williams. This holiday tradition, which seems to extend all the way back to 1963 in Nashville when Willis Page directed it on December 15th, is proving to be one of the highlights of the holiday season in Music City.

Oddly enough, however, in 1742 when Handel wrote his masterpiece oratorio, it was not designed to be performed during the Christmas season but rather during Lent as a more restrained and religious entertainment than Handel’s secular operas which along with their competition where flooding the London market. Thus, the oratorio in general lacked the scenery and staging of traditional opera and emphasized a sacred rather than a secular topic. Handel more than made up for this in his musical setting, especially in the

recitatives, which span a continuum from the reduced “secco” instrumentation of voice and keyboard to the fully accompanied recitatives in which the vocal line is inlayed within the full orchestra’s texture. Maestro Guerrero’s handling of these recitatives was quite remarkable from the very opening number, “Comfort Ye, My People” as sung by Sorenson.

We last heard tenor Garrett Sorenson last month in the Symphony’s production of Rachmaninoff’s The Bells. With a strong and well-polished instrument, Sorenson leant a warmth to Handel’s ornamented melodic line. In “Every Valley Shall Be Exalted” the text painting came across as sincere and without contrivance, a great achievement in so well know a work as this. Similarly, Foster-Williams’ bass brought new life to his line and coupled it with a supple tone that drew on a remarkable clarity in diction, his interpretation of “The People that Walked in Darkness” was terrifying and yet expressed the inlaid hope for redemption.

Mezzo-Soprano Elizabeth Batton was refreshing in her interpretation, and her voice blended exceptionally well with Sorenson’s (Batton’s husband) in the second of the work’s two duets “O Death, Where Is Thy Sting.” Another magnificent moment was Soprano Mary Wilson’s performance in the delightful shift from secco recitative to the accompanied (“And the Angel Said unto Them” followed by “And Suddenly there Was with the Angel”) that opens the second half of Part One. She created a nuanced dramatic shift that articulated her character’s awareness behind the words she was singing as though her recognition of the “heav’nly host” emerged slowly in its presence-a moment well-articulated by Maestro Guerrero’s delicate direction.

However, the star of the performance, as it should be, was Tucker Biddlecombe’s marvelously well-prepared Nashville Symphony Chorus. Their diction, balance and intonation were remarkable, particularly in the Hallelujah anthem and fuguing chorus as well as the remarkable “Amen” chorus that ended the piece. Special mention goes to Nashville’s amazing strings led by Jun Iwasaki and the two trumpets that announce the Hallelujah chorus, they managed, with Handel’s reduced orchestra, to fill the magnificent Schemerhorn Hall with music—a great challenge with concerts such as these. In all the evening was a refreshing performance of the canon’s oldest chestnut—a marvelous holiday gift for the Music City!

the Nashville Symphony

“Neglected Jewels” and “Pristine Acoustics:” Paul Jacobs Returns to Nashville

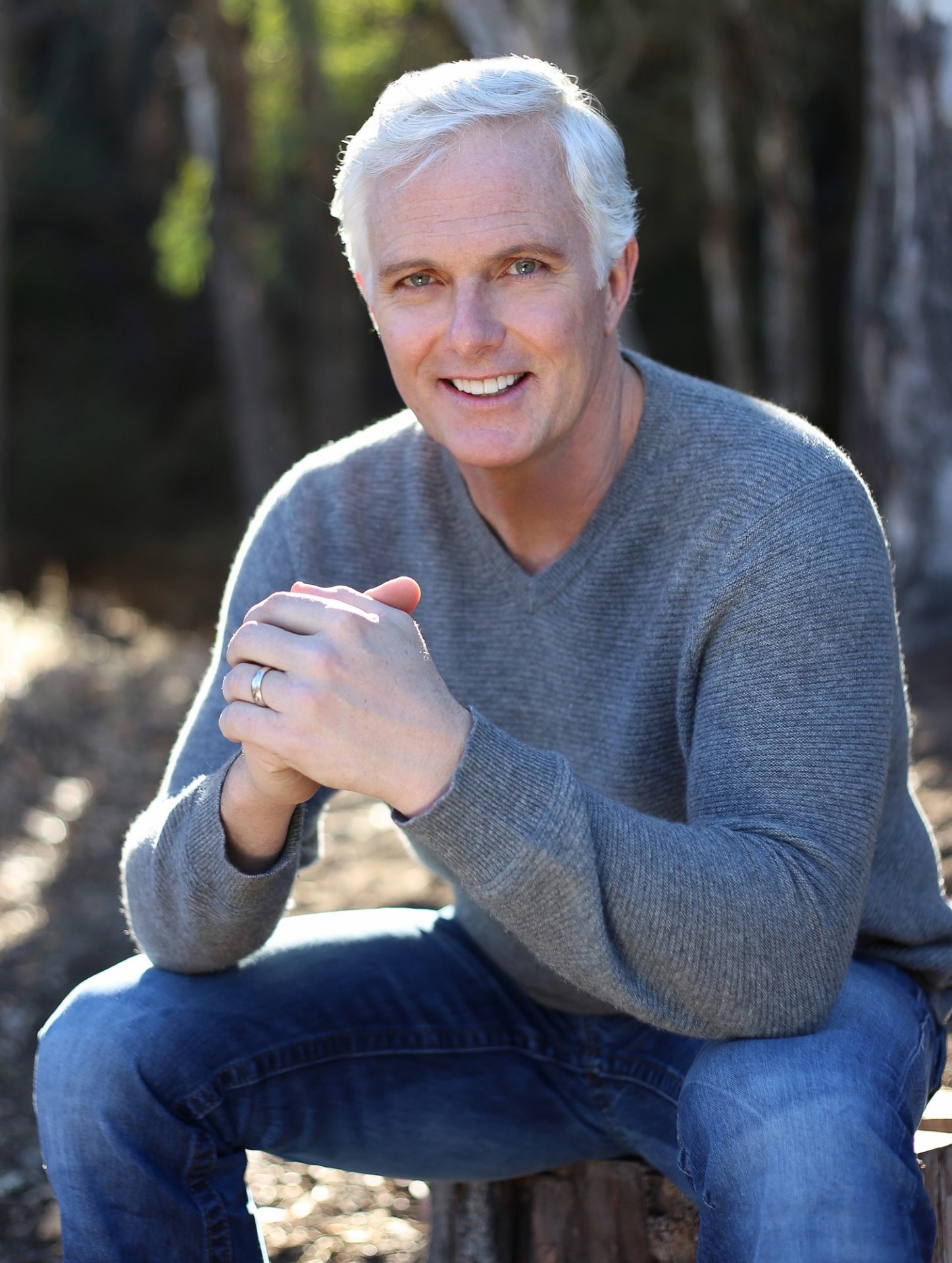

Ahead of his visit to Nashville on November 21-23, when he will play Horatio Parker’s Concerto in E-flat Minor for Organ and Orchestra, Op. 55 in concert with the Nashville Symphony, we had the opportunity to ask virtuoso organist and Grammy winner Paul Jacobs about the piece, performing at the Schermerhorn with the Nashville Symphony and about his instrument.

Ahead of his visit to Nashville on November 21-23, when he will play Horatio Parker’s Concerto in E-flat Minor for Organ and Orchestra, Op. 55 in concert with the Nashville Symphony, we had the opportunity to ask virtuoso organist and Grammy winner Paul Jacobs about the piece, performing at the Schermerhorn with the Nashville Symphony and about his instrument.

MCR: We are quite excited for you to come visit Music City to play with the Nashville Symphony! Could you tell us something about how the project got started?

PJ: It’s been a tremendous pleasure to have worked with Giancarlo Guerrero on several occasions, most recently with the Cleveland Orchestra, when he suggested it might be exciting to record a program of American organ concerti in Nashville. Given the abundance of repertoire for organ and orchestra (much more than people realize), it wasn’t difficult to identify some marvelous works that deserve to be heard by audiences and recorded for posterity.

MCR: What can you tell us about Horatio Parker’s Organ Concerto? Are there highlights in particular that we should listen for?

PJ: Horatio Parker’s organ concerto is a neglected jewel, a work of striking craftsmanship and deep feeling. Parker was an important American composer of the late-19th century, part of a group known as the “Second New England School”, whose music was strongly influenced by the German tradition. Warmly Romantic in style, this concerto tears at one’s heartstrings. A soaring melody is heard in the opening bars of the music, carrying the listener into an alluring yet wistful landscape. The first movement concludes with a dialogue among organ, violin, horn, and harp–pure gold. The Scherzo-like second movement provides a touch of effervescence, levity, and wit. The full glory of the organist is made manifest in the final movement, replete with virtuosic pedal writing and a dramatic cadenza. It’s thrilling to play, believe me!

MCR: You have performed in Nashville before, indeed in 2017 your world premiere of the revised version of Michael Daugherty’s Once Upon a Castle for Organ as performed with the Nashville Symphony and Maestro Guerrero (on Naxos) won a Grammy Award. What is it like to play with Guerrero, the Nashville Symphony and on our Martin Foundation Concert Organ?

PJ: I’ve only the highest admiration for Giancarlo Guerrero, a consummate artist. He leaves no stones unturned, and his intelligence and passion are inspiring, on the podium and off. It’s an honor to join him and the Nashville Symphony–a stellar orchestra in every respect. Given all the musicians involved, the Schermerhorn’s pristine acoustics and world-class pipe organ–all the stars should be in alignment for this special project!

MCR: As chair of Juilliard’s organ department, a touring virtuoso, and champion of not only the canonical repertoire but also of contemporary music for the instrument–solo and collaborative–what would you say is the state of the organ in the classical world?

PJ: Though the organ has been on the periphery of classical music for quite some time, I’ve dedicated my life to doing all that I can to bridge this gap. This is due to a host of complex reasons that could fill a book (which I might write one day), but suffice to say the glory of the instrument continues to shine brightly through performances in every corner of the world, with audiences eager to listen. Once a New York Times critic told me that, in his experience, the two most devoted groups of music lovers where opera buffs and organ fans. Many in the classical music establishment seem unaware of the widespread devotion and support the King of Instruments actually has.

MCR: What other instruments do you play? Do they inform your interpretations at the organ?

PJ: The piano was my first instrument, which I began studying seriously at an early age and continue to play almost daily, though not in public. As an undergraduate student, I frequently played harpsichord, primarily for the opportunity to play chamber music. Making music with others has always been important to me–something not often expected of organists. And, yes, playing one keyboard instrument inevitably informs (and sometimes transforms) another, expanding one’s concept of musical expression.

MCR: Your marathon performances of the complete organ works of J.S. Bach and Olivier Messiaen have given you a legendary status in the classical music world. You also made history by becoming the first organist to receive a Grammy Award for a solo recording of Messiaen’s Livre du Saint Sacrement. Personally, do you have a favorite performance of your own?

PJ: This may be impossible to answer, given the ephemeral nature of live performance. But there are also too many happy experiences to recall, fortunately! I will say that some of the most meaningful encounters I’ve had have been with audiences in smaller communities and in more intimate settings. People crave beauty, wherever in the world they happen to live.

MCR: After Nashville and this recording, what’s next?

In addition to upcoming solo recitals, later this season I’ll be joining Giancarlo in Europe for performances of a concerto by the late Stephen Paulus. Also, the Daugherty that we recorded in Nashville I’ll be playing with the Philadelphia Orchestra in February (having just performed it with the Kansas City Symphony last month). Then I’ll be joining the Utah Symphony for a Handel organ concerto and Samuel Barber’s Toccata Festiva, which I recorded last season with the Lucerne Symphony in Switzerland. Finally, I’m anticipating the release of a recording made with the Cleveland Orchestra of a riveting organ concerto, Okeanos, by contemporary Austrian composer Bernd Richard Deutsch.