At Oz Arts Nashville

New Dialect Performs Poignant Double Feature

Six amorphous figures appear on a dark stage as music fades in. The figures split into pairs and slow dance as the lights go up. It’s the kind of slow dance that you see in movies. The kind of movies where it takes an hour, a break up, and a triumph of the will before the two main characters, in a high school gymnasium turned Sadie Hawkins dance floor, realize that they were meant for one another. The girl rests her head on the guy’s chest as they share – if only for a moment- completeness. This is how First Fruit, Rosie Herrera’s new ballet, opens, the only caveat being that each of the characters are covered head-to-toe in Post-It notes.

Grants from the N.E.A., the Tennessee Arts Commission, Oz Arts, and the Danner Foundation made this world premier possible. In January of 2020 Herrera conducted a week long workshop with 67 participants from across the country. In the weeks following she collaborated with the dancers of New Dialect to create First Fruit; the the first of two works on New Dialect’s program last weekend at Oz Arts Nashville.

Warm and familiar-sounding Spanish music serves as a soundtrack while the neon squares of paper dance from the performers to the floor. Soon enough the stage, which had started black, is littered with bright colors. As layers shed from the dancers, bright street clothes and leotards are revealed. It is difficult, with a work of this nature, to nail down a specific and concrete meaning, but the performance is broken into roughly four main movements. Each scene seems to explore different endings to romantic relationships: heartbreak, drifting apart, abuse, and lasting love (in no particular order). One memorable scene features a female dancer who slowly and methodically rips a fallen post-it note to shreds. A male dancer, on the opposite end of the stage, writhes in agony with each motion. The end of each scene is heralded by the company rushing out and using a cardboard flap to cover a character (or characters) as they lay on the ground.

The integration of the post-it notes as costume, prop, and set is brilliant. The choreography itself is inventive in that it is always subservient to the narrative. The production runs a full gamut of emotion. It is quirky, sad, strange, beautiful, passionate, and mesmerizing.

The second production of the evening was The Triangle by Nashville Native and founder of New Dialect Banning Bouldin. This work, which played to sold out crowds last year, is a visceral and emotional study on our cultural obsession with overcoming. In a pre-event discussion she described this work’s unique creative process. Bouldin, a sufferer of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, described her first attack as the catalyst for this work. “3 and a half years ago I experienced my first episode of MS. I spent the first 36 years of my life an advancedly coordinated, athletic, professional dancer… I woke up one morning unable to feel my legs. I had tremendous difficulty balancing and walking. It was a very scary time for me. I Remember crying when I was sitting in my car and realized I wasn’t going to be able to drive myself… and having the very reassuring thought that I don’t have to be able to walk and I don’t have to be able to dance to make dances”.

Bouldin’s experience with MS opened a line of questioning which led to the development of 13 short works that she calls “Limitation Etudes.” She describes The Triangle as a natural outgrowth of these ideas. Confinement and constraint play a major role throughout the work. It opens on an ensemble of dancers connected in a maze of straps. As one dancer escapes she does so at the expense of another. At times it is difficult to watch; paralysis is an uncomfortable thought. The dancers found themselves confined to chairs. They are limp and powerless as the hands of others drag them across the stage. They fall and struggle to get up, and that was the most moving part of The Triangle for me. However difficult it was, they never stopped striving to get up. The dance is an artistic statement about our societies’ romanticization of striving that resonates far beyond physical disabilities.

This stint of shows will launch New Dialect into a three year touring initiative of these productions. They were one of five Southeastern dance companies to be selected by SouthArts to participate in the program. These works will continue to have life and meaning in other towns and communities as New Dialect acts as a cultural diplomat for the Music City across the country.

the Nashville Symphony

Beethoven and Genius: an Interview with Maestro Guerrero

This weekend, February 20th through the 23rd, Nashville Symphony will present an all-Beethoven concert, including the ground-breaking Eroica symphony, the somewhat confusingly titled Leonore Overture No. 3 (one of several written for Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio), and the classically oriented Piano Concerto No. 1. The concert is dedicated to the 250th birthday of the composer, which will occur in December of this year.

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 in Eb major, often spoken of fondly as the Eroica, short for Sinfonia Eroica (“Heroic Symphony”), marks the transition between music of the Classical era and the beginning of the Romantic era. Beethoven built upon the musical foundation of his predecessors, synthesizing the styles of Mozart and Haydn while innovating in virtually every facet of the classical symphony; form, harmony, dynamics, and emotional content are all expanded upon.

Fidelio is Beethoven’s only opera, though he did compose a number of overtures for it in an effort to set the opening scenes as effectively as possible. Leonore No. 3 is actually his second attempt, and though widely considered the best as a piece of music, audience members found it to be overwhelming compared to the relatively light scenes at the start of the opera. The Piano Concerto No. 1 is the earliest of the three compositions, and thus the influence of Haydn, and especially Mozart are clearly heard here. Yet Beethoven’s voice is unmistakable and his mastery of the classical forms of Sonata and Rondo undeniable.

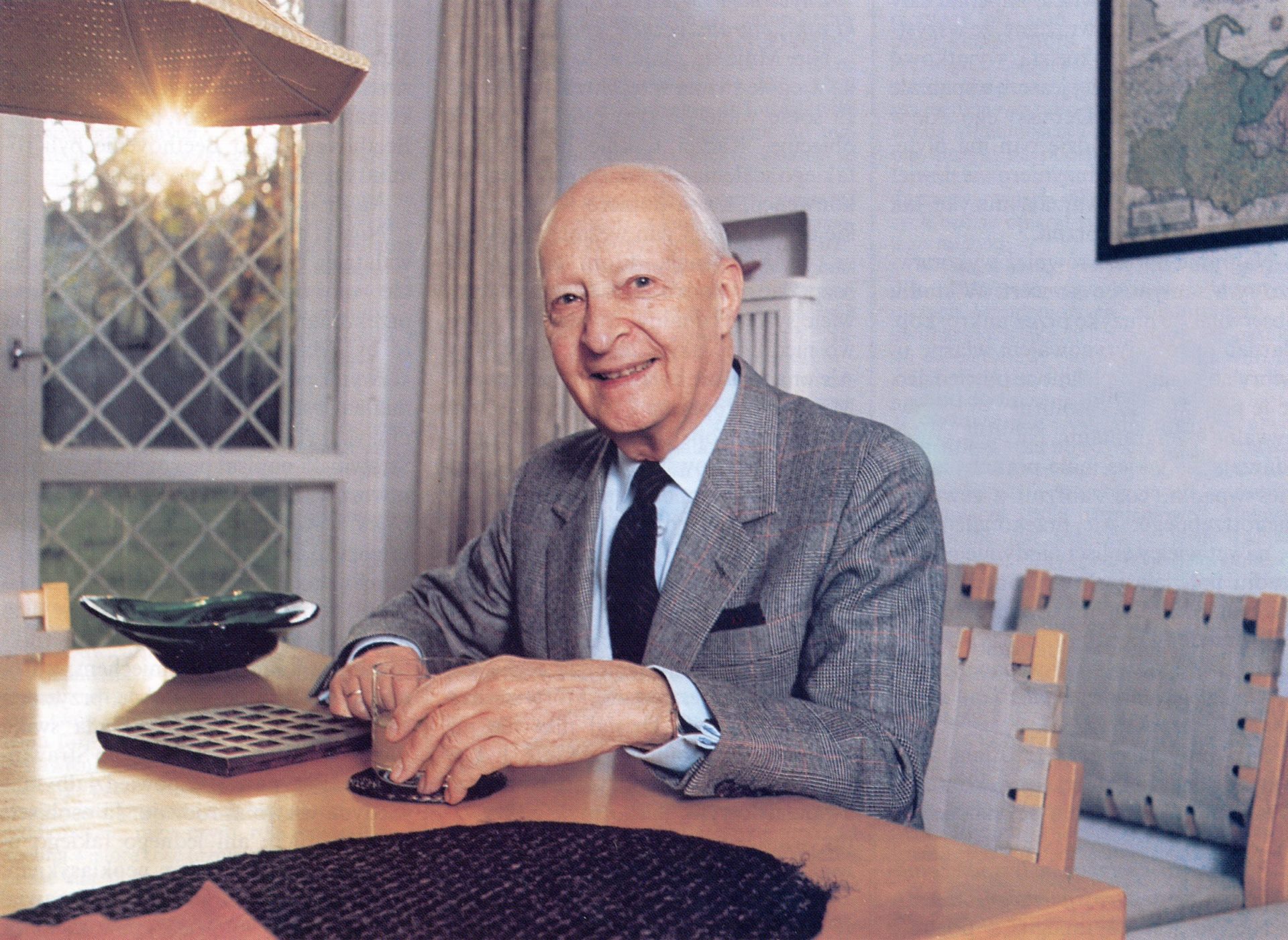

This past Monday I had the honor to speak to Maestro Giancarlo Guerrero who will be conducting this weekend.

Jack Marlow: Good morning Maestro.

Maestro Guerrero: Hello, how are you?

JM: Very good, thank you for taking this time out of your schedule, I really appreciate it. So we are going to talk about Beethoven, my first question, kind of a nebulous one, but what do think Beethoven means to us today, why is he relevant in your view?

MG: Well you know the same things that inspired him in the early 1800s, in terms of passions and politics and love, depression, and challenges in one’s own life have not changed in human beings, so I think there’s a deeper connection. When we listen to not only Beethoven, but all great composers, going back hundreds of years, their music sends a message that is very much relevant to today’s world. In many ways we are able to understand what are the things that truly inspire us. Really he is no different from artists nowadays who are writing things that are almost a time capsule of the times in which they are living.

I promise you at that point, that is my favorite piece on the face of this earth.

JM: Right, thank you. Time for an easier question, do you have a favorite piece by Beethoven, any instrumentation, piano or-?

MG: You know what, it’s really whatever I am conducting at the time, to be honest with you. That is one of the questions we get asked the most as musicians, that’s almost like asking which is your favorite daughter or son. In many ways the best answer I can give you is whatever I happen to be working or conducting at the time. And the reason is very simple, you have to remember that we program our seasons sometimes two or three years in advance, so there is a kind of long gestational process of preparing the piece, getting it ready, deeply analyzing it, so finally you get in front of an orchestra and an audience and you’ve been waiting three or four years sometimes to get the piece done, so I promise you at that point, that is my favorite piece on the face of this earth. Because then when it’s over, it may be a long time before that piece comes back again, so it’s like spending time with a dear friend, and then you hope you get to spend time with that friend again in the future, and sometimes it can be another five, ten years, or maybe never, you never know how these things work.

JM: Yeah I feel that way just as an audience member. I’m a huge fan by the way, I go to every classical series concert I can. Why these specific pieces? It makes sense, with the Eroica, but why the first Piano Concerto?

MG: A lot of it has to do with scheduling, over the last few years we have done the other four concertos kind of recently, and the first it’s been almost nine years. So a lot of time it just kind of comes down the scheduling, which pieces make it into a program. One reason this program came together is that I wanted to showcase three aspects of his writing. In the case of Leonore 3, this was written for his only opera Fidelio, and then his piano concerto is basically the standard for piano players – they master each of the five. And then in this case the scheduling helped narrow it down to the first one. Then the Eroica, to me it’s been a while since I’ve done it, since I believe my first season here in 2009. So it’s a piece I haven’t done myself in a while, and I wanted to bring it back, and in many ways this is the one symphony that basically shattered the existing ideas of classical structure in classical music- traditions of music that were left by Hadyn and Mozart. Beethoven broke it immediately with this one piece and in many ways this one symphony is the starting point of what became the Romantic period. No slow introduction, just two very big, loud chords – I’m sure it must have been very shocking to the audience, and to this day it sounds very fresh. And plus the political inspiration of this piece that originally was written for Napoleon, Beethoven was a big admirer of the ideals of the French Revolution – equality, democracy and so on. So when Napoleon declared himself emperor, Beethoven became so enraged that he actually ripped off the title page, removed the dedication to Napoleon, and instead dedicated it to the memory of a great man.

JM: Fascinating.

MG: Remember that during the time Beethoven was writing this, during the Napoleonic wars, he himself had to deal with bombings from the French, they bombed Vienna during his lifetime. So these were very turbulent political times. And in human history those are always around, so in many ways this piece represents a time capsule of the turbulent political times that were being lived through in Europe at the time.

JM: Right, thank you. Possibly relevant to our own times. How many times have you conducted the Eroica?

MG: Once. Can you believe that?

JM: Wow-

MG: I’ve only done it once, and if you were to ask me why, I couldn’t give you an answer. Many of these things just fall off on the side, without any reason. I mean we have to go through so much repertoire every season, that every now and then it takes a moment for you to say “hang on a second, why haven’t I done this piece in a while, I love it.” So the fact that we have this birthday, this is the opportunity. Really doing it now – there’s a part of me that feels a little guilty. It’s been such a long time, and not for any particular reason. It just never came around, not on my radar, but now I promise it is very much on my radar.

JM: Have you learned anything specific in the score, details perhaps that didn’t jump out last time?

MG: Oh of course! Always, you know there’s always new editions coming out, new scholars that come out with new information, revised, and further exploration of the manuscript. Like any other great piece of music, great piece of art, it’s a living organism, these things evolve over decades and centuries. And we have to keep re examining them with fresh eyes and fresh information. Plus you have to remember I am not the same person I was ten years ago. So I’m looking at this from a very different perspective of a person who has been with the orchestra for more than ten years, and my kids were very little, and now I have teenage daughters – of course that’s going to affect my music making! How could it not, like when you read a book the second time you see different things because you’re basically a different person. So for me it’s always exciting because I get to know an old friend and love them even more. A lot of the things we find out have to do with logic – sometimes there is some ambiguity with things like articulation, or dynamics, and when you study the pieces further you apply logic – you almost have to guess really, like CSI Beethoven_ I’m trying to figure out what they were writing. Even now with computer programs that write music, like Finale or Sibelius, they are not perfect. I do enough world premiers to know even modern pieces have some ambiguity. So imagine two hundred years ago these people were writing with ink and pen, smudge all over the paper by candlelight – of course there’s going to be mistakes. So it’s up to us to use the best of our abilities to figure out exactly what it is the composer intended. In some cases, the worst part of it – there is a very fine line between a bad mistake and something brilliant. Whether the composer was going for something very unique or it’s just a mistake – there’s a fine line. It’s the same fine line between crazy and genius. So a lot of times you are forced to make what I call executive decisions.

…to be a genius at that level… I think there has to be a certain degree of madness

JM: Genius is an interesting one to discuss, you could think of Beethoven as the man that pioneered and really popularized that concept in the western imagination. Do you think genius exists and did Beethoven have it?

MG: Of course it does! But as I said, to be a genius at that level… I think there has to be a certain degree of madness associated with this. Because you’re seeing the world, I believe, in so many different layers, they have the ability to process information in a way that most normal people don’t have. By the way Beethoven was not by far the first, we could go back to Da Vinci, Michelangelo, we could go back to Mozart. These were artists and human beings that left such a mark that even to this day we are in awe at the things they did. Because as I said they process information and put it into their own art or artform , and it’s simply astonishing. When you think about the amount of work these people left – in many cases a very short period of time, and without the comforts of modern technology that we have nowadays. I think it’s just a complete miracle. And for those of us who do this, for me in particular, I find it incredibly inspiring and it’s a wonderful excuse to walk away from the craziness that is the 21st century with its fast-pace. When you get to sit down with a work that’s forty-five minutes long, and really delve into the mind of a composer, that like most of us had great experiences but also inner demons. All of that is seen very clearly in his art, and the same could be said of Mahler, Stravinsky, Mozart Van Gogh, Picasso, and any other great artist to this day that is making us reconsider the meaning of life in many cases.

JM: So you mention Mahler, Stravinsky – it’s kind of hard after the death of Stravinsky to think of a leading composer of the 21st century, the Beethoven of our time if you will. Who would you say is that person?

MG: To me, John Adams. He is by far the most performed music composer on the face of this Earth. And so we can go by that, John Adams has been able to find, I think, a following, while he’s alive he’s been able to enjoy great success, that even Beethoven would have wished to have, or Mozart. So there are some that I think have continued to set the standard, but he is not by far the only one. Think of Penderecki in Poland, or Philip Glass. I think what you are describing is that since we have such access to information right now – well back then the composer had a more slow recognition time because it took sometimes years for us to hear the pieces that were premiering in Europe to get to the United States, or vice versa. Nowaday when a piece gets premiered in Berlin we are able to hear it immediately. So that creates a much bigger pool of composers for us to pull from. There’s just so much easily accessible music immediately on our phones.

JM: With the Eroica, the 19th century is often framed musically as a debate between the programmatic and the absolute, Wagner versus Brahms and so on. Do you hear the Eroica as a programmatic piece, and if so do you have a kind of story or program in your mind?

MG: Well remember that the original inspiration for this was Napoleon, and the ideals of the French Revolution. There’s a degree of anxiety that came along with something so shocking in the history of Europe. The French revolution – I mean there was great fear among the monarchies of Europe because this was the beginning of the end for them. And of course as usually happens with big political upheavals all of the plans and works that the people promised, none of them came to fruition. I mean that is always the case, they always promise the wonders of the Earth, and then at the end the reality is that the personalities take over and usually it becomes a problem, a dictatorship. So the fact that Beethoven thought of Napoleon and the French Revolution experiment – you can hear that in the music, that he was feeling alongside everyone in Europe. Even if the composer did not intend to write something about something in particular, how can they separate themselves from their own personal lives? Whether it’s something associated with love, or in the case of Beethoven personal challenges, realizing at the time he was becoming deaf. All of these things must have an impact. So I don’t think there is a thing called absolute music. Even Mozart, who may have written 41 symphonies – everyone of these works were written at a time when something was happening in his life and this must have had an impact.

JM: I’m no Beethoven scholar, but I know there’s somewhat of a controversy about his original tempo markings, and I was wondering what your thoughts were about that.

MG: Yeah well it’s not so much of a controversy, what happened is that Beethoven knew Mälzel who invented the metronome. And as you can imagine the first prototype of it was not perfect. And we now know that the metronome Beethoven had access to was not quite precise. So a lot of scholars will tell you that some of the tempo markings, all of them if you ask me, seems a little on the fast side. But then again, it’s hard to say for sure. What we do know is that after getting the metronome Beethoven was so excited to have a new toy, that after the fact he started putting metronome markings on all of his pieces. He wanted to test his new machine and see how well it worked with his works. There’s been I believe two or three recordings of the Beethoven cycle recently where the big selling point is “oh we’re using the Beethoven markings.” Well you know what, they don’t work in some cases, sometimes they are just over the top fast, and you don’t get to really appreciate the music because it’s moving too fast. Beethoven was a master of the inner voices, and if the music is going too fast you miss out on the intricacies in the middle. Even the most demanding composer in my lifetime has never told me “it’s 72 to the quarter note, and it has to be 72 to the quarter note – “ Never! Every single one of us as conductors or performers have to put our own personal stamp on it. For me these metric markings are more of a starting or reference point. What’s more interesting though, to me, is the relationship between the movements. 120 in the first movement, 60 in the second movement, you know the second was intended to be half as slow. To me that is much more interesting than the number itself. Because the number was dictated by the acoustics of the hall, the virtuosity of the orchestra, and the personality of the conductor.

JM: Right, checks out to me at least. Last question: what do you see as the future of classical music in general, and in Nashville specifically?

MG: We are living in an incredible time of access to information. Orchestras these days are absolutely incredible. Nashville Symphony is a world class, virtuosic orchestra that can tackle not only the challenges of Beethoven or Mozart, but also the great challenges of recording live the music of our time from living American composers. I truly believe that orchestras need to continue to reach out to their communities. It is our responsibility in Nashville and in the rest of the world, for orchestras to service the people that live in those communities. Orchestras really should enrich the quality of life of the communities that they belong to. And Nashville is no different, I’m very proud to belong to a city that is proud to call itself Music City. And there is so much activity – great quality world class music activity happening in Nashville. The symphony needs to remain relevant, we need to remain a part of that environment, of what makes Nahville important So far us, it is all about servicing and bringing music to our community and making sure that this music has relevance in what is happening in Nashville. We just really have to think about – what you program in Nashville should be very different from what you program in New York, very different cities. A big part of it is really trying to keep your ear on the ground and figure out what Nashville needs from the Symphony. And as long as you do that you’re always going to have music lovers come and continue to support it. And remember this question was also being asked around Beethoven’s time, “what is the future of music?” Things haven’t changed, Beethoven was new, Mozart had world premiers. This is nothing new. The question that continues to be asked is making sure that the music we play has a place at the table, and that people feel a connection to it personally and spiritually. But we have one of the best concert halls on the face of this Earth so that helps a lot.

JM: Well I can speak for myself that I love Nashville’s programming, I’ve learned a number of new composers I had never heard of, and I’ve gotten to enjoy some standards – I’ve never gotten to experience the Eroica live so I’m really excited for this weekend.

MG: Sweet. You know, it’s funny this actually is a really unusual program for us – Beethoven, a one composer program, and he’s dead, so kind of unusual program for us.

JM: Can’t wait to hear it, thank you for speaking with me Maestro, have a great day.

MG: Thanks so much Jack, take care.

I am confident that Maestro Guerrero will have the depth of knowledge and the personal warmth required to bring out the best of Beethoven’s music, Nashville is fortunate to have the chance to see such a skilled conductor and orchestra perform some of the best music composed in such a beautiful concert hall.

Nashville Ballet

Blurring Ballet Lines: A Series of Moving Dialogues on Gender Identity and Stereotypes

Does movement imply gender? Do accepted norms impact freedom of self expression? Is creativity subconsciously limited by culturally-imposed stereotypes? These are the types of questions choreographers Carlos Pons Guerra, Erin Kouwe, Matthew Neenan, and Jennifer Archibald grappled with in Nashville Ballet’s production of “Attitude—Other Voices.” As cultures, expectations, and expressions shift over time, this type of artistic commentary uniquely provides a tangible interpretation of human struggle and progress.

“Private Balls,” choreographed by Carlos Pons Guerra, provided a wonderfully curious, yet poignant perspective on the desire to dance together, specifically with someone of the same gender. The piece portrayed countless elements of what desire looks and feels like, but no movements were depicted in an overtly sexual manner; rather, the array of emotionally charged gestures conjured feelings of incredible beauty, melancholy, longing, hesitation, relief, and wonder. With a variety of romantic and post-romantic pieces provided by the accomplished and sensitive Alessandra Volpi at the piano, the dancers portrayed an inspiringly non-traditional narrative against the underlying conventional ballet music.

Contributing to the personal-feeling storyline of the ballet was the enchanting, innocent voyeurism that attended the costume collection of the dancers. The all male-presenting cast of characters wore an eclectic collection of undergarments ranging from boxers, undershirts, vests, briefs, and dress socks, to long-sleeve silk shirts, gauzy tops, bow-ties, and cummerbunds. As each pair danced together, the language of movement exhibited an array of feelings between the couples: love, humor, passion, wistfulness, freedom, and security among others. As the narrative unfolded of one particular dancer facing his own desire to dance with another, the audience moved through the journey with him, experiencing the breadth of movement-invoked emotions along the way. Guerra’s choreography juxtaposes quaint charm with emotional gravitas, intimating out-of-reach experiences and emotions for an audience hungry for understanding.

Erin Kouwe’s “Auto Poet” elicited a much more philosophical response to gender roles, cast with all female-presenting dancers in a variety of pure white, androgenous apparel. Kouwe described the process behind the piece in her choreographer’s notes: “Our work began with individual hyperlogic: each dancer moving toward the desire of their own method of physical thinking. We pulled apart the threads of that logic, slowed it down, observed, and defined it in order to know the desire that made it. Does the desire embedded in our logic reveal any subtext about who we are? … The limitations feel at once arbitrary and powerful. Pulling apart the threads of limitation and desire led us into chaos and closeness.”

With insight into the cognitive origins of this piece, the choreography is immediately recognizable as a reflection of that process. To the untrained eye, movements are combined in such a way as to seem random yet matter-of-fact, focused yet chaotic, angular yet graceful, and pieced together in a strange yet beautiful way. Perhaps due to the movement choices, but also influenced by Louis York’s original music, the piece took on a sense of contemporary, authentic beauty, highlighting unrestrained expression in an intellectually provocative way. Kouwe’s compelling language of expression deconstructs boundaries, inspiring curiosity and awareness.

Matthew Neenan’s “There I Was,” with a lush yet minimal, emotionally integral score composed by Christina Spinei, was born out of the choreographer’s own experiences with loneliness. Highlighting a career spent surrounded by fellow dancers yet constantly feeling alone, Neenan captured the internal battles fought by questioning gender expression in the ballet world. With contemporary artwork by Vadis Turner suspended from the rafters above the stage and intriguing costuming providing stark contrast between vibrancy and shades of gray, Neenan’s large-scale choreography of a 25-person cast wove all elements together into a work of emotionally affecting grandeur.

Following the main character, portrayed by company member Brett Sjoblom, the audience was drawn into an emotionally-wrought journey of questioning, gender exploration, alienation, denial, torment, resolve, and recognition. Sjoblom’s interpretation and characterization of this role conveyed an intimate, passionate, and unlimited understanding of Neenan’s choreography, communicating emotional fervor in every step, bend, and gesture. The use of such a large cast added an incredible depth to the overarching message of the work, portraying a wide array of human experiences and emotions, banding together in the end en masse, seemingly seeking the same thing collectively: acceptance.

“Posters,” with choreography by Jennifer Archibald, original music by Louis York, and poetry by Caroline Randall Williams, served as a dialogue about womanhood and re-claiming feminine-associated stereotypes, characteristics, and experiences. Archibald notes about her creative process, “I have focused on the women, and the untold experiences that women may or may not choose to share. To take gendered norms and re-conceptualize, reclaim and subvert them in ways that are active, self-governed choices is empowering.”

Beginning with all black, simplistic costuming, male and female-portrayed dancers interacted in smaller groups of twos and threes, enacting experiences in which the women’s actions were dictated, expectations were set, or specific reactions were assumed. Archibald’s choreography reflected each female figure’s internal struggle, movements suddenly shifting from compliance to conflict and back, jarring the audience’s understanding of each interaction. With Louis York’s songs titled “Raging Bull” and “You and I,” a sense of uncomfortable unrest began to build, eventually arriving at a passionately charged dialogue reflecting the relationships on the stage.

With intermittent spoken word by Williams, the music continued to grow, swelling with up-beat, soulful, world-inspired sound as dancers one by one appeared in a new black and yellow costume and a brightened outlook, changing the narrative to one of empowerment and joy. Each couple now moved with equal intention, seeming to support the other without any expectation, definition, or assumption. Louis York’s song “Posters” embodied the message Archibald chose to champion in the piece, defying all cultural impositions and seeking to redefine womanhood in whatever shape it chose to take. As the final work and program came to a close, the audience responded overwhelmingly with genuinely appreciative applause and a standing ovation, smiles inspired on faces and hope instilled in hearts. Nashville Ballet’s decision to commission new ballets on such a culturally relevant theme was a timely and exceptionally welcome one, continuing to cultivate an audience eager for inspiration and artistic commentary for an ever-changing world.

At the Public Library

Intersection Celebrates Black History Month

I’ve been to a lot of concerts. I’ve seen Beethoven Symphonies and Handel Oratorios. I’ve laughed at Papageno in The Magic Flute and held back tears as Mimi dies in La bohème . I’ve sat quietly through four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence and been bathed in the cacophonies of Varèse. On more than one occasion I have seen Bach Inventions performed on Boomwhackers. Today, as I took my seat in the auditorium of the Nashville Public Library, I realized that I was about to witness something I had never seen: a piece of Western Art Music written by a composer of color.

In celebration of Black History Month, Intersection (under the direction of Maestro Kelly Corcoran) has programmed an entire series of concerts which exclusively feature music by Female African American composers – namely Florence Price and Nkeiru Okoye.

Today’s program included selections from Okoye’s opera, Harriet Tubman – When I Crossed That Line To Freedom (2014). The work chronicles the life of Harriet Tubman (played by Soprano Brooke Davis) as she makes her way from a sickly slave girl to the leader of the Underground Railroad. The role of Rachel – Tubman’s Sister – was played by Tamica Harris (Soprano), and Charles Edward Charlton (Baritone) served double duty as both Harriet’s husband John and Father Ben. Corcoran led a piano sextet in accompaniment, and narration was provided by Tasneem Ansariyah Grace, Associate Director of the Nashville Public Library.

Notable moments from the selections included I Want A Man, wherein a young Rachel (expertly sung by Harris) espouses her wish to marry and raise children. This piece foreshadows the character’s coming inner battle: to flee slavery or stay with her family. Nothing But The Grave – a duet between Harriet and Rachel – demonstrated not only the deep bond between two sisters but also the operatic mastery of the two performers. Brown Skin Gal , which was described by Charlton as “an ode to Black Women,” gave the singer an opportunity to show off his powerful voice, along with his fearless ability to engage an audience.

The show-stopper of the afternoon was the final selection, I Am Moses, The Liberator. This aria’s libretto was modeled after the famous Tubman quote: “If you hear the dogs, keep going. If you see the torches in the woods, keep going. If there’s shouting after you, keep going. Don’t ever stop. Keep going. If you want a taste of freedom, keep going.” and portrayed Harriet confronting a slave who, after deciding to flee, voices his desire to turn back. Davis delivered an emotional moment that truly encapsulated the strength and passion of one of history’s most heroic characters (and hit a high G that would knock your socks off).

American History is filled with a myriad of laudable African American figures: King, Douglass, X, Marshall, Parks, Dubois, Washington, and Hughes – just to name a few. Tubman, beyond a shadow of a doubt, belongs in this pantheon. I left today’s performance feeling inspired and grateful to have witnessed the honoring of a legacy that continues to provide light to a people who have, time and time again, been so unfairly and overwhelmingly marginalized in this country.

Later this month Intersection will host two additional concerts. The first will occur at 7 pm on Saturday, February 15th at Fisk Memorial Chapel. Entitled “Upon These Shoulders – From the Back of the Bus”, the program will honor the legacy Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and many other heroes of the Civil Rights Movement. Florence Price’s Four Negro Songs In Counterpoint will serve as the concert’s centerpiece. The final event – simply named “Journey” – will include a performance of Price’s Spring Journey by The Women’s Chorus from MTSU. Additionally, “Journey” includes a discussion between Indiana University’s Dr. Alisha Jones and Vanderbilt’s Dr. Douglas Shadle, which will focus on the unique voices of Okoye and Price. This event will take place at 7:30 pm on Thursday, February 27th on campus at Vanderbilt’s Blair School of Music.

I would strongly suggest making room in your calendar for one (or both) of these events. Not only will you hear enjoyable music executed on a high level and have the opportunity to engage in responsible discussion on African American history, you will also witness one of the rarest things in Classical Music: a piece not written by a dead white guy.

From that other Broadway:

My Fair Lady: The Perfect Musical Reboot at TPAC

In 1913, when George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion was first premiered in Europe, the world was in turmoil. World War One was approaching and the labor movement in the United States and Europe was well underway, with the Colorado Coalfield War, considered to be the deadliest labor unrest in American History beginning in September of that year. In England, at the Epsom Derby, suffragette Emily Davison died as she tried to grab the reins of King George V’s horse. The world at the time proved quite dramatic and it is no wonder that in their entertainment they sought escapist literature. Perhaps this is why Shaw’s “rags to riches through phonetics” narrative became so popular. It is a

quaint story and when it was adapted for the Broadway stage by Lerner and Loewe in 1956, as My Fair Lady, it had the luck of an amazing cast staring Rex Harrison and Julie Andrews, getting the longest run of any show on Broadway up until that time and it has been called the “perfect musical.”

The early February production at Andrew Jackson Hall in TPAC certainly demonstrates the work’s “perfect musical” status. With Michael Yeargan’s sumptuous sets, Professor Higgin’s house features the best of a Victorian bourgeoisie décor, and excellent period costumes by Catherine Zuber, at the very first glance the musical is breathtaking.

As the ragamuffin-cum-duchess, it would be difficult to overestimate Shereen Ahmed as Eliza Doolittle, the title character. A fetching brunette with a voice that is more than reminiscent of Andrews, her character’s creator, Ahmed dominates the role. Her performance of the big number, “I Could Have Danced All Night” was wonderful, not just because of her excellent intonation and timbre at forte, but the piano, a soft, intimate delivery that gave chills. Further, her diction, and her part is a transcendental etude in diction, is at turns funny, amazing, and always believable, particularly in the “Ascot Gavotte” where she mimics character after character while maintaining a naiveté balanced by street smarts. Her character is incredibly complicated and she depicts it in a magnificent way.

Her male counterpart, Laird Mackintosh as Professor Henry Higgins, is self-centered, educated and confident, but with remarkable flashes of vulnerability that enrich his character. Also, Mackintosh’s delivery of what may be the worst line Shaw ever wrote: “I know you’re tired, I know your headaches, I know your nerves are as raw as meat in a butcher’s window” is a believable articulation of his character’s difficulty with being appropriate himself. The two of them together have a great energy and tension; Ahmed’s natural charisma, just as one assumes Andrews had quite a bit of charisma over Harrison, allows you to clearly see how the plot is going to develop and yet enjoy every step along the way.

Christopher Gattelli’s choreography to Lerner and Lowe’s orchestration is magical and ridiculous, the highlight of which is “Get Me to the Church on Time,” sung by Eliza’s fun-loving father Alfred Doolittle (played by a hilarious Adam Gupper) in an ensemble piece that alone makes this reboot remarkable. Professor Higgins’s mother, Mrs. Higgin’s, is a wise, worldly and pragmatically feminist woman endearing performed by Leslie Alexander. Professor Higgin’s sidekick Colonel Pickering, as played by Kevin Parseau, is also remarkably endearing, entering into the pantheon of mildly homoerotic sidekicks (think Batman and Robin, the Lone Ranger and Tonto or Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson.). In “Why Can’t a Woman Be More Like a Man,” he is wholly supportive of the Professor, but in the silly trio “The Rain in Spain” his presence supports the tension between the Professor and Eliza.

As a testament to its success, and despite rather significant cuts from the original, the evening I saw this production I forgot for a couple of hours that our President was being impeached, the caucus results in Iowa were in a questionable flux, and the corona virus was spreading rapidly around the world. This is to say it is a delightfully successful production and every bit escapist as it should be.

At the Schermerhorn

The Conductor Saves the Day: Romantic Rhapsodies at the Schermerhorn

On the weekend of January 30 through February 1 the Nashville Symphony presented a concert titled Romantic Rhapsodies which featured Johannes Brahms Third Symphony (No. 3 in F major), George Enescu’s First and Second Romanian Rhapsodies (Op. 11, No. 1 & 2) as well as Béla Bartók’s two Rhapsodies for Violin and Orchestra featuring Nashville’s own Concertmaster Jun Iwasaki on violin. It was an evening of virtuosity and artistry.

Johannes Brahms’s Third Symphony, particularly the first movement, is an exemplary essay in the process of thematic development, witnessed first in how the grandiose

opening theme, first characterized by a two note gesture, is developed and proceeds to a rustic, even pastoral conclusion in the middle of the exposition. This theme was brought out and delivered with a nuanced enthusiasm by the orchestra under the baton of Lawrence Foster, an American conductor born to Romanian parents and who specializes in the music of Enescu. The rustic feel was further embellished by the opening movement’s second theme, warmly given by Titus Underwood (Oboe) and James Zimmermann (Clarinet). Overall the entire symphony was wonderful. Indeed, Foster’s abilities to maintain a delicate balance in Brahms’ nostalgic orchestration, particularly in the Andante, this time with Zimmermann’s clarinet with Julia Harguindey’s Bassoon, demonstrated that this Enescu expert also knows his Brahms, and very well at that.

The second half of the concert opened with Bartók’s Rhapsody No. 1. Both of Bartók’s Rhapsodies are incredibly difficult pieces, written not as commissions, but to be dedicated to personal friends and violin virtuosos Joseph Szigeti (the first) and Zoltán Székely (the second). Both rhapsodies are built on a pre-existing Hungarian genre, the verbunkos, which Bartók set within a western classical context. The opening slow movement (“Lassú”) was well begun with Foster coaxing the often striking dissonance of Bartok’s accompaniment from the orchestra in a spellbinding manner, particularly the otherworldly Hungarian cimbalom (hammered dulcimer), at the same time maintaining a restraint that allowed the Iwasaki’s virtuosic line to shine through. Then, however, at some point

half way through the second movement things began to feel off center. Whether it was the shared tempi or the dynamic balance, the movement finished unconvincingly and Iwasaki smiled with great relief. The Nashville audience applauded, but Iwasaki and Foster were in an intense conversation. Soon, Foster turned to the audience and spoke:

In a concerto, when something goes wrong “…you can blame the soloist, or you can blame the orchestra, but in this case it was the conductor’s fault.” He then turned back

to the orchestra and asked to restart from what I believe was rehearsal number 16. This decision was clearly adored by the audience as they clapped their approval. Suddenly, the Bartók began to sparkle. Iwasaki’s phrasing and warm tone emerged gently from within Bartók’s busy, at times nostalgic and at others cacophonous, accompaniment. The ending, now a glorious culmination, was rewarded by the entire audience leaping to their feet. In the second of Bartók’s Rhapsodies, there were no issues, it was performed with lively, and endearing abandon, reminding us all that Iwasaki is one of the cultural treasures of the Music City.

As for the Enescu, I much preferred the second movement with its interiorized songlike expressions as heard at a dance. In particular, one could hear in Foster’s conducting a recognition that Enescu’s deployment of folk themes are not the subject of his work, but instead the marvelous orchestral colors within which they are set.

As I left the concert that evening, and in the time since, I have thought about Foster’s decision to replay the ending of the Bartók. In the end, to have risked personal criticism as a conductor in order to ensure that the audience heard their ensemble, soloist and Bartok’s work in the best interpretation is a remarkably selfless and laudable act; indeed it saved the evening’s performance! As shown with both the Brahms and the Bartók, a great conductor makes great decisions and I hope I get a chance to hear him again soon. The Nashville Symphony returns on February 20 with Beethoven’s Birthday Bash.

Nashville Opera

A Nightmare at the Opera – Britten’s Turn of the Screw

“A male figure introduces a curious story written in faded ink, in a woman’s hand” – a dry and concrete assertion begins the synopsis of Britten’s Turn of the Screw, one of the only grounding statements in this tale’s slow creep towards the nebulous and macabre. The Noah Liff Opera Center’s intimate thrusted stage provides a perfect setting for this chamber opera. close-packed audience can mark every horrified expression; performers have easy access from the stage for ghosts to waft out into the room and wail out of sight; utilitarian steel girders in the high ceiling require little imagination to perceive as murky church rafters or solid schoolhouse beams. Sparse decor in the form of dangling pure white figurines at various heights above the stage accompanies the minimal set pieces – a desk, bed, or few chairs are the entirety of furniture. Singers, instrumentalists, and lighting carry the show, easily enfolding the audience on this Friday night.

Scored for just 13 musicians, the prologue of the show opens with solely piano to provide a soundscape for the narrator, introducing Britten’s ever-shifting harmonic palette that flirts with serialism but never dives off the deep end. Some of the flourishes are reminiscent of Schoenberg’s writing in his 3 Klavierstücke, but beyond some rhythmic similarities their harmonic approaches to applying tone rows are vastly different. Michael Anderson’s “Prologue” establishes the setting with warmth and delicacy, giving away nothing of his dual role as Peter Quint later on.

The workout for the chamber orchestra takes many forms across the fifteen variations on the 12-tone row of the ‘Screw theme’, providing constant material to stitch together the scenes’ changes of locale and passage of time. From off-kilter rhythmic unisons, to every pairing of instruments to form every duet imaginable, or solos in staggered entrances and key areas – hearing the group put through their paces by Dean Williamson, conductor, covered the gamut from breathtakingly kinetic to serenely meditative. A treat, in this setting, to be so close to the instruments and be able to feel the low end from the piano, strings, and woodwinds, negating the proximity effect that frequently robs audiences in larger spaces the physical impact lower frequencies provide.

As each character is introduced we hear their talents both soloistically and in small groups, and with voices this skillful it is hard to say which context is preferable. Lara Secord-Haid as The Governess held such consistency

of tone while navigating leaps and bounds through the phrases built on the underlying serial concept, while Kaylee Nichols’s voice as Mrs. Grose filled the small theatre to overflowing with sound and clear diction. Their duets during Act I Scene 2: “The Welcome”, as The Governess first arrives and meets the children, and Act I Scene 3: “The Letter” when Miles is dismissed from school, combine the sounds to be an even more soaring sum of its parts, expounding on fondness for the children and the hopeful attitude of The Governess for an enjoyable post at the house.

No less of a surprisingly excellent match of blend and timbre are the voices of Caleb Killingsworth as Miles, and Helen Zhibing Huang as Flora. From their first entrance, their actions often ranged in tandem, initially from mere childish antics at school through to the mockery of hymns and the horrors of possession. It is vital that these characters mesh well in sound and behavior – Huang and Killingsworth are more than up to the task. Tom Tom the Piper’s Song was a particular marvel of a duet, shifting the melody ever higher into the stratosphere with apparently effortless ease. While neither are children (Killingsworth a counter-tenor junior studying at Nashville’s own Belmont University, Huang recently finishing a Young Artist Residency at Portland Opera), wonderful singing and convincing portrayals allow for forgiveness. Convincing 10-and-8 year olds to sing a 12-tone opera at 8 PM on a Friday would be a hard sell!

As an admitted John Wick stan, it was enjoyable to see a similar tactic of “tell don’t show” applied to the foul legacy of Peter Quint before his actual appearance. Muttered tales of his felonious behavior (“Quint was free with everyone… with little master Miles… he liked them pretty and he had his will, morning and night”) set up an impactful full entrance of the character after the first sightings. The explosion of sound emanating from Mrs. Grose, wailing “Dear God” when The Governess first describes the face of the ghost, is a memory that will remain in the brains of the audience for no short amount of time.

The pressure on Michael Anderson and Micaëla Aldrige to imbue their respective Peter Quint and Miss Jessel roles with a commanding amount of effective creepiness is heightened through the first act until their proper appearances. After such a buildup of exposition and tantalizing glimpses of their characters at the edges of the theatre and in offstage sung lines, the audience was well-rewarded for their patience. Britten, so careful to hint at horror and skirt around the edges for so long, firmly lands in that territory near the end of act one and into act two with possessions, candles being snuffed, and creepy children’s tunes. One can only imagine what the audience felt going in blind to the premiere in 1954, supposing they hadn’t read the book. With the minimal set design and stage props, it was a treat to see the presence of some classic horror tropes as well in the form of a pig-head-on-a-stick being paraded around and twisted contorted poses by the possessed children for the entracte variation to begin Act II.

Peter Quint as portrayed by Michael Anderson is a slimy figure of deft manipulation and delicate control. Plaintive crooning of Miles’s name as he slowly lures the child to his sway is, well, haunting, while the stark lighting under the stage casts enigmatic craggy shadows to his face – the audience must rely on the emotion in the voice to perceive Quint’s desires more than physical expression. Noticeable at times with other characters as well, such as some of The Governess’s less defined reactions – with the audience so intimately close by it seems a lost opportunity to forego stronger facial expressions. In more energized moments however, such as Quint’s insistent queries regarding the letter in Act II, the motivations come through clear as day in the middle of this dark performance. Perhaps as a result of Britten’s own biases in writing the Quint character for Peter

Pears, the role of Miss Jessel is not quite as dynamic, although Micaëla Aldrige handles it well. Her duet in Act II with The Governess was a highlight, navigating the rubbing dissonances at times written a direct half step off from the orchestra, leaning into those moments and reveling in the effect with confidence.

Finally, mention must be made of the excellent lighting design throughout, courtesy of Barry Steele’s work. The stage itself consisted of milky translucent panels through which light was projected, resulting in stark edges and long shadows. Combined with the overhead banks and some amazing and varied textures could be created. The sense of motion created for The Governesses opening journey by train was a particular marvel, while scenes at the lake contained a wonderful rippling effect of muted greens and blues that felt naturalistic and organic rather than gimmicky. Scenes in night varied from warm dusky hues of purples to more grim whites to great effect, and easily aided in fleshing out the scenes’ minimal sets.

With a densely tragic journey packed into a two-hour production on a Friday night in January, the audience was left wrung out at the conclusion of the evening. Britten’s Turn of the Screw was a bold and evocative programming choice to start the new year and new decade of programming. Nashville opera will return in the spring with a production of Rigoletto in April at the Tennessee Performing Arts Center. “