A Review of ‘Human Resources’ presented by Nashville Story Garden and OZ Arts Nashville

As a trailblazer that continues its commitment in supporting the out-of-the-box local and international theatrical expression, OZ Arts Nashville doesn’t seem to shy away from transforming itself to accommodate the needs of the artists it hosts.

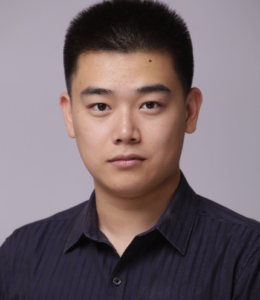

For Human Resources, written by Nate Eppler (award winning playwright and director of Playground writing incubator), directed by Lauren Shouse (award winning director, currently Assistant Professor of Theatre Directing at Middle Tennessee State University) and devised and developed by Nashville Story Garden, the stage is turned into an arena, one of the more common formats of contemporary experimental theater. Following Geoff Sobelle’s Food, this is the second time I experienced a performance at OZ Arts Nashville in this format. It is very fitting for a performance that aims to expose an exaggerated portrait of corporal dynamics, its hierarchies, and the meaning(lessness) of the concept of work and work-life in today’s success-driven positivist warp.

Human Resources is a purposefully fractured theatrical experience, delving into the idle work lives of the manufacturers of a pharmaceutical corporation whose external image is an inverted facade of the values it promotes. The staging has an immersive nature, and it invites the audience to a thoroughly curated encounter. A somewhat participatory experience with orchestrated transitions in perspective that may pose a challenge for those with mobility issues, which is why the promotion of the performance should have advised this feature. The performance handout states the nature of audience participation; however, the handouts are only given out once someone is entering the stage and has already committed to experiencing this show.

The tone is set at the foyer or behind the limits of what has been taken in as a stage: filing cabinets, folded computer parts, screens where Dr. Goodapple (Geoff Davin), the representative of Liminal, promotes the ten tenets of Liminal Corporation, under impersonal jazz tunes. A commercial promoting Zealiva, a drug that improves productivity at work and helps workers fulfill Liminal’s tenets, occasionally takes over the screens, reminding us of the unconsented commercials to products we are exposed to in our everyday lives. There’s a witty wordplay happening right there: ‘liminal’, or in between, which gets further opened during the performance and ‘zealiva’, a drug that activates zeal and pushes workers to feel alive, when they are actually feeling demotivated because they hate their jobs!

In the waiting room, the audience is also offered signature “9 to 5 Collins drinks”, promoted as fully utilizing citrus fruits. Unmistakably, a reference to the feminist comedy Nine to Five directed by Colin Higgins, starring Jane Fonda, Lily Tomlin, Dolly Parton, Dabney Coleman, Elizabeth Wilson, and Sterling Hayden.

The Liminal staff, apropos, the actors of the play are promoted on a company poster, and at another corner, a tribute is paid to the deceased worker Judy, whose values have been calculated in percentiles within the scale of the company, while later, the reaction to her death on her work desk during her weekend overtime has been memorized by the workers and is robotically replayed with a mimicked gesture and the wording: “So sad, so sad!”.

The set design (Diana DeGarmo), props design (Madeleine Hicks) and lighting design (Phillip Franck) turn the OZ Arts Nashville stage arena into a floor of the Liminal Pharmaceuticals’ headquarters. The branding of the office materials including the Liminal logo (designed by Chris Ammons) looks so genuine, it pushes one to question whether we should believe in the legitimacy of anything that has a brand design. Boxes of Zealiva are spread all over and we can see the staff arriving and saluting the logo of the company with militaristic gestures (Is this what one could call Corporate Patriotism?), before they disappear into their cubicles, performing motorized and repetitive movements. A worker’s chair has its nylon wrapper still on, a signifier of the sterility, discomfort, and the detachment of the workers from their working space.

Every few minutes, a Squid Gameish sound (sound design by Tasha AF Lemley) announces ideological breaks to remind the workers of the tenets of the corporation. This is pleasingly choreographed and is a testament to Nashville Story Garden’s dedication to extensive teamwork in devising their works and their emphasis on incorporating physicality to storytelling on stage.

The fourth wall in this performance is broken when the audience members are addressed as “external stakeholders” alias consumers. This also alludes to the awareness that the actors are being watched, another reference to George Orwell’s 1984, although they don’t hesitate to go through their full arch which is ardent and rocky.

The simulation of utilitarianism is broken when Harper (Lauren Berst, also co-director of Nashville Story Garden) comes in to address an HR issue: an anonymous complaint of a worker from this particular floor. While the complaint boxes are available, based on how the rest of the storyline develops, complaints not only seem to not lead to the improvement of the work environment, to the contrary, they may cause even more harm and might backfire. Harper’s language and behavior are an exact portrayal of an HR representative, and this produces a lot of humor when heard on stage and accompanied by exaggerated grotesque acting. The play is filled with sparkling farcical punchlines such as “empty seats disrupt focus”, “check the pulse”, or “Jargon will not save you!” (- Andie, played by Meggan Utech) that are familiar to the audience and burst them into laughter, same as when Dr.Goodapple wears a VR set, to enter the “profit envisioning center”.

As we rotate our seats, we get to experience the work life of those in the cubicles. Other critical commentaries on corporate work life such as workers not fully knowing their jobs because of their partial training, as in the case of Beenz (Tamara Todres, also co-director of Nashville Story Garden) or Blake (Joe Mobley), the only one who knows how to do a certain job of handling cables, speak to the absurdity of bureaucracy that recalls Franz Kafka’s remarks on the establishment. While we can partially hear the drama on the other side of the cubicles, we can’t see it nor are able to fully focus on what’s happening in front of us, so we’re curious, distracted, disturbed and anxious because we are missing out! This fragmented perception intends to pose the crucial question that the production team of this performance wants the audience to ask themselves: How can we relate to anything if we’re constantly being fed with fractured experiences?

A significant breaking point occurs with the empowerment of the janitor Loggs (Bakari King) when he breaks his observational silence and expands his role to what others at this office envy: that his life extends beyond the walls of Liminal. Thus, the play also becomes a reflection on loneliness and the meaninglessness of the life-work split which undoubtedly made many audience members whisper the name of the TV series Severance.

The performance ends in a rather depressing point. Andie’s declaration: “There’s always one more step that keeps them where they are and us where we are” is backed up by the immediate replacement of the holder of the leather chair, while the lower ranked workers will go back to their everyday routine.

Human Resources, is undoubtedly one of the most experimental and poignant theater pieces developed and staged in Nashville in the past few years. The impressive focus on details and the hard work of the performance team was clearly visible. The mobility issue was skillfully managed by the OZ Arts staff, but a mobility warning would have been needed for this performance.

Norma y la Reinvención de la Tragedia: Reflexiones desde Florencia

Version in English Here

En la cuna del humanismo cada dimensión del ser se erige en un fascinante balance entre el pasado y la contemporaneidad. La introspección espiritual resuena en acústicas esferas impregnadas de pigmentos y de ambición. La estética se sobrepone a la dicotomía moral y los obstinados lapsos de ingenio desprenden un aroma que distrae a la conciencia. Aunque ajena a la abstracción florentina, la esencia de Norma alberga intricados desafíos internos en su efigie de perfección.

Los días 9,11,16 y 18 de marzo, el Teatro Maggio Musicale Fiorentino (antiguo Teatro Comunale) recibe por sexta vez el montaje de la ópera Norma de Vincenzo Bellini. La moderna maquinaria escénica dio libertad a las vanguardistas aspiraciones del director de escena Andrea De Rosa para que la experiencia visual acentuara las particularidades de la historia. El diseño circular semi inclinado de madera ámbar del auditorio, se integró perfectamente con la representación en bronce de la casta diva cuyo esplendor cubrió al público durante gran parte de la obra. El reloj marcaba las 8 P.M. en punto cuando el espíritu marcial de la obertura se abrió paso en una sólida interpretación de la Orquesta del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino. El telón se levantó revelando a un grupo de soldados camuflados con tan solo sus ojos descubiertos que sometían a los guerreros galos halándolos de sus extensos cabellos. A partir de este momento el entendimiento se separó de la escucha para tratar de descifrar la tan ecléctica representación. El atuendo de las milicias causó estupor; en la incapacidad de comprender inmediatamente esta alegoría, mi subconsciente se sobrecogió ante lo que puede suponer un inminente peligro de deshumanización. Conforme la escena iba avanzando fue posible distinguir que los largos cabellos rubios de las guerreras y guerreros se sujetaban de sus cubrecabezas y de la armadura, respectivamente.

Andrea de Rosa argumenta que su estilo teatral se enfoca en “observar la actualidad desde otros ángulos” y confirma que los soldados modernos representan la ferocidad de milicias como el ejército estadounidense perpetrando torturas en la prisión iraquí de Abu Ghrab. Esta visión contemporánea se combina con rituales arcaicos en una escena siguiente, en la que, vigilados por el enemigo, los galos a través de la danza sumergieron, sacudieron y golpearon los mechones de cabello contra el agua de un pozo que se erigió como altar ceremonial en medio del escenario. La instalación de claroscuro recreó la atmósfera justa para la mítica aria insignia del bel canto, “Casta Diva.” La soprano australiana Jessica Pratt, reconocida por su maestría en este exigente estilo, articuló cada figura con una frescura y propiedad tales que resultaba difícil creer que este fuera su debut como Norma. El público no logró contenerse e irrumpió la exhalación final con un estruendoso aplauso.

Bellini parece entregar muy pronto la joya de su composición; no obstante, la suprema pericia en el desarrollo melódico, donde cada nota está cuidadosamente pensada para potenciar la prosodia del texto, da lugar a una sucesión de arias, duetos y tríos, que son una fábula para los sentidos. El director Michele Spotti complementa esta opinión con que la “música misma es la palabra” y que a través de la conexión instrumental entre cada escena “el drama fluye en una corriente de emociones y sensaciones que mantienen siempre vivo el discurso musical.” En efecto, ese laberinto de pensamientos que atraviesan Norma, Adalgisa y Pollione, contribuye a que la composición se estimule con repentinas transiciones anímicas. Un ejemplo puntual es el recitativo confesional de Pollione (Mert Süngü) y Flavio (Yaozhou Hou) “Svanir Le Voci.” El estilo declamatorio de Bellini suele tener una articulación más versátil para dar variedad a las prolongadas líneas que dedica a Pollione.

Si el desprendimiento de la pesada cubierta del pozo que en su lento ascenso fue encarnando la sustancia del satélite natural, parecía ser el efecto más impactante del montaje, el inicio de la séptima escena fue aún más insospechado. El escenario se eleva hasta la mitad, revelando en las profundidades la habitación de un búnker amoblado y protegido con dos puertas de seguridad a los lados. Dos columnas dividen el espacio en tres secciones, separando las distintas secuencias teatrales y musicales que ocurren simultáneamente. En el primer cuadrante, un camarote alberga a una niña y un niño en pijama, que retozan y duermen. Norma, ahora luciendo un atuendo doméstico, reafirma la coexistencia de dos universos. El personaje de Clotilde (Elizaveta Shuvalova) está enteramente comprometido con proteger a los infantes del caos familiar y no pierde oportunidad para estrecharlos y acariciarlos. Un exceso de afecto que roza lo empalagoso. Sin embargo, los niños buscan este contacto, extendiendo sus abrazos a cada personaje presente.

Andrea de Rosa recrea este sobrecogedor lienzo para evidenciar que, independientemente de la época, los niños han sido víctimas de crisis intrafamiliares y de la guerra, condenados al aislamiento y al encierro. Fue desgastante presenciar en segundo plano a dos criaturas atrapadas en la monotonía, cuyos altibajos emocionales reflejaban los dilemas de su madre. A pesar de la zozobra, Bellini entrega duetos inspiradores como “Mira o Norma.” La elaborada y cristalina homofonía entre Norma y Adalgisa (Maria Laura Lacobellis) desplegó un resplandor prismático en medio del lúgubre recinto. Posteriormente Pollione encara su falta y se une a la discusión femenil en complicidad melódica con la orquesta.

La introducción al segundo acto ya no tiene un tono marcial, y la sentida melodía de los cellos vaticina una despedida. El escenario regresa al universo de los galos, pero la cuántica introduce un nuevo elemento surrealista: un arsenal de pistolas y fusiles para enfrentar a las milicias. Norma también reemplaza la daga de la historia por un arma de fuego. Sin embargo, no aparece con ella en el búnker con la intención de apagar la vida de sus hijos, un detalle que humaniza aún más al personaje en esta versión. El altar se transforma en una hoguera abstracta, y los mechones de cabello vuelven a participar como símbolo ceremonial antes de convertirse en lazos que amordazan a Norma y Pollione en su sacrificio mortal. La monumental polifonía del final en la que las líneas de Oroveso (Riccardo Zanellato) y el coro se entrelazan suplicantes soportadas por el contundente anuncio de los cornos y la percusión, nos gratifica con la última sorpresa teatral. El escenario se eleva nuevamente y las paredes del búnker están recubiertas de ansiosos garabatos infantiles y palabras como “casa” y “mamma.” Recostada sobre este elocuente muro, yace la niña en un deseo infructuoso de liberarse y a unos pasos su hermano, en conjunto estado de locura.

Un público familiarizado con la pureza del repertorio italiano estalló en ovaciones para el reparto, el coro y la orquesta. La atemporalidad del montaje y la creatividad en la escenografía y el vestuario, se tradujeron en una exhibición de impecable diseño. Michele Spotti custodió cada nota para que la esencia romántica permaneciera impoluta, y la orquesta encauzó cada dinámica y cada fraseo en amplia excelencia.

From Our Far-flung Correspondents Series:

Norma and the Reinvention of Tragedy: Reflections from Florence

Versión en español aquí

In the cradle of humanism, every dimension of being erects in a fascinating balance between the past and contemporaneity. Spiritual introspection resonates within acoustic spheres infused with pigments and ambition. Aesthetics overlap the moral dichotomy, and obstinate lapses of ingenuity release an aroma that distracts the conscience. Though foreign to Florentine abstraction, Norma‘s essence harbors intricate internal challenges in its effigy of perfection.

On March 9, 11, 16, and 18, the Teatro Maggio Musicale Fiorentino (formerly Teatro Comunale) welcomes the sixth staging of Vincenzo Bellini’s Norma. The modern stage machinery granted free rein to the avant-garde aspirations of stage director Andrea De Rosa, ensuring that the visual experience heightened the nuances of the story. The auditorium’s semi-inclined circular design, crafted from amber-toned wood, blended seamlessly with the bronze representation of the casta diva, whose splendor enveloped the audience for much of the performance. At precisely 8:00 p.m., the martial spirit of the overture emerged in a solid performance by the Orchestra del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino. The curtain rose, revealing a group of soldiers, their faces concealed except for their eyes, subjugating the Gaul warriors by yanking their long hair. From that moment, comprehension detached itself from listening, seeking to decipher this eclectic representation. The attire of the militia provoked astonishment; in the immediate inability to grasp this allegory, my subconscious was overwhelmed by the looming specter of dehumanization. As the scene unfolded, it became clear that the warriors’ long blonde hair was secured to their helmets and armor.

Andrea De Rosa asserts that his theatrical approach focuses on “observing the present from other angles” and confirms that the modern soldiers symbolize the brutality of military forces, such as the U.S. army perpetrating torture in Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison. This contemporary vision merges with archaic rituals in a subsequent scene, where under the enemy’s watchful gaze, the Gauls, through dance, submerge, shake, and strike their locks against the water of a well—an altar-like centerpiece on stage. The chiaroscuro installation conjured the perfect atmosphere for the mythical bel canto signature aria, “Casta Diva”. Australian soprano Jessica Pratt, renowned for her mastery of this demanding style, articulated each figure with such freshness and precision that it was hard to believe this was her Norma debut. The audience could not restrain themselves and interrupted the final exhalation with thunderous applause.

Bellini seems to present the jewel of his composition quite early; however, his supreme skill in melodic development—where each note is meticulously crafted to enhance the text’s prosody—gives way to a succession of arias, duets, and trios that become a fable for the senses. Conductor Michele Spotti complements this idea, asserting that “the music itself is the word” and that through the instrumental connection between each scene, “the drama flows in a current of emotions and sensations that keep the musical discourse perpetually alive.” Indeed, the labyrinth of thoughts traversing Norma, Adalgisa, and Pollione fuels the composition’s emotional transitions. A prime example is the confessional recitative between Pollione (Mert Süngü) and Flavio (Yaozhou Hou), “Svanir Le Voci.” Bellini’s declamatory style often displays a more versatile articulation, offering variety to the extended lines he dedicates to Pollione.

If the slow ascent of the well’s heavy cover—gradually embodying the substance of the natural satellite—seemed to be the most striking stage effect, the start of the seventh scene was even more unexpected. The stage rose halfway, unveiling the depths of a furnished bunker-like room protected by two security doors on either side. Two columns divided the space into three sections, separating the simultaneous theatrical and musical sequences. In the first quadrant, a bunk bed housed a girl and a boy in pajamas, frolicking and sleeping. Norma, now dressed in domestic attire, reaffirmed the coexistence of two worlds. The character of Clotilde (Elizaveta Shuvalova) was entirely devoted to shielding the children from familial chaos, seizing every opportunity to embrace and caress them—an excess of affection bordering on saccharine. Yet, the children sought this closeness, extending their arms to every character present.

Andrea De Rosa paints this shocking tableau to illustrate that, regardless of the era, children have been victims of both domestic crises and war, condemned to isolation and confinement. It was exhausting to witness two little beings trapped in monotony in the background, their emotional fluctuations mirroring the mother’s turmoil. Despite this anguish, Bellini delivers stirring duets like “Mira o Norma.” The elaborate and crystalline homophony between Norma and Adalgisa (Maria Laura Lacobellis) cast a prismatic glow amid the somber setting. Later, Pollione confronts his transgressions and joins the female discourse in melodic complicity with the orchestra.

The introduction to the second act sheds its martial tone, and the cellos’ poignant melody foreshadows a farewell. The stage returns to the Gaul universe, but quantum dimensions introduce a surreal element: an arsenal of pistols and rifles to face the militia. Norma also replaces the historical dagger with a firearm. However, she does not wield it in the bunker with the intention of extinguishing her children’s lives—an alteration that further humanizes her character in this rendition. The altar morphs into an abstract pyre, and the locks of hair once again serve as ceremonial symbols before transforming into bindings that tether Norma and Pollione to their mortal sacrifice. The monumental polyphony of the finale in which the lines of Oroveso (Riccardo Zanellato) and the choir intertwine, pleadingly supported by the forceful announcement of the horns and percussion, gratifies us with the last theatrical surprise. The stage rises once more, revealing the bunker’s walls covered in anxious children’s doodles and words like casa (home) and mamma. Resting against this eloquent mural, the girl lies in a futile yearning for freedom while her brother, a few steps away, is lost in a state of madness.

An audience well-versed in the purity of the Italian repertoire erupted in ovations for the cast, the choir, and the orchestra. The timelessness of the staging and the creativity of the scenery and costumes resulted in an impeccably design exhibition. Michele Spotti safeguarded each note to ensure the romantic essence remained pristine while the orchestra channeled every dynamic and phrasing with boundless excellence.