Live Music in Nashville

Nashville Composer Collective at Asaph’s Chamber

This past Sunday afternoon (September 20th) the Nashville Composer Collective (NCC) put on their 22nd program in Belmont University’s intimate Asaph’s Chamber. Chairs were spread out out throughout the space either alone or in pairs and accommodated about 25 audience members. The concert, lasting barely under an hour, was an unpretentious presentation of six varying works and resulted in six individual successes. Personally, I was tremendously excited for this performance as it was the first live music event I have attended in over half a year.

John Darnall, Director of the NCC, introduced each piece and its’ composer, offering them the opportunity to say a few words about their work. First up was Melanie Alvey with her piece Mountain Echoes orchestrated for three violins (one electrically amplified and hooked up to a looping station), viola, cello, and electric bass. Opening with a solo violin creating a multi layered loop of an asymmetric groove, gradually the rest of the ensemble comes in building on the established beat. This piece was pleasing both aurally and visually seeing the opposing violins echoing gracefully back and forth to each other over the ostinato. Mountain Echoes was a personal favorite of mine on the concert and it is always a treat to see the composer performing their own work.

Up next was Jack Williams’ Emergence for string quartet. Steeped in 20th century compositional techniques, Emergence is a mature piece that gripped me from the start. Quartal and quintal harmonies mix with contrapuntal techniques, motives bounce around the ensemble, and lyrical melodies are contrasted with jagged sections. Although there was much going on throughout the piece, one never lost their way and could easily follow the logic of the piece.

After two string ensembles the concert moved to Joodils by Andre Madatian for flute and piano. Translated from Armenian, Joodils means “Little Bird.” This work was written for his Grandmother who recently passed and who always enjoyed bird song. The flute, depicting the bird calls, was complemented with the supportive harmonies of Nathan Girard at the piano who occasionally also echoed some of the bird calls. Special appreciation should be given to Jess Benevento on the flute, who tackled the virtuosic flute part with great poise and fantastic technique. Overall Joodils was a great joyful piece that is a fantastic memorial to Andre’s grandmother’s memory.

Beginning the second portion of the event was Jeremy Smith’s song cycle I Don’t Admire You Like I Did When I was 21 In the Spring. This included three short songs: Drug Store Train Trip, Jersey, and Your Apartment in Soho. Jeremy set the words of Aurora Bodenhamer, a poet who he found on Instagram (and also did the hand drawn cartoons for the accompanying lyric sheet). Erin Hildebrandt, sang her way beautifully through the score which was filled with tricky harmonic intervals and impressive leaps. The music was thickly set to the rather unassuming poems, and Jeremy was able to draw out the humor and color of the words.

Kyle Baker’s Divertimenti for Clarinet and Piano was up next. This was a beautiful piece that featured the clarinet, played brilliantly by Raymond Ridley. Melodies led the piece from one section to the next with the clarinet usually taking the lead. It was solidly constructed and would make for a great repertoire piece for any clarinetist. My one complaint is that we were only treated to the first movement, entitled Wandering.

Ending the program was the first movement of John Darnall’s “String Quartet #1” that he was recently commissioned to write. Similar to the other quartet on the program, this piece drew inspiration from 20th century techniques, and John masterfully infused them with his own colors and ideas. Of particular interest to me was the wonderful treatment of the pizzicato within the piece. Sometimes it served as an accompaniment to other melodies, and in differing places it was a technique featured throughout the entire ensemble.

The concert was a great success for each of the composers and the whole Nashville Composer Collective ensemble. It is always a treat to hear new music, and especially so when the composer is still alive and able to talk to you about their work. I look forward to attending many more concerts and supporting the NCC in all that they do, and I would encourage anyone reading to support the ensemble.

Add comments or questions below!

A New Release from Orange Mountain Music

From the Intimacy of Quarantine, Simone Dinnerstein’s “A Character of Quiet”

The tumult of 2020 has brought trials and tribulations to all, but as people discover silver linings in enjoying more time at home or taking up a new hobby to pass the time, the fall looks to bring fruits of artists’ labors. With tours cancelled and performances postponed, musicians’ “quarantine albums” and projects have been churning out across all genres as the summer has passed, with no sign of this trend slowing. American pianist Simone Dinnerstein’s contribution “A Character of Quiet” offers an intimate home recording, pairing Philip Glass and Franz Schubert to great effect.

Being cooped up obviously affects people in different ways. While a restless energy may translate to productivity and inspirational focus for some, others may struggle with the suspension of routine and stagnant scenery at home. When preparing for this project, Dinnerstein notes her own struggles with the situation, bluntly speaking how “candidly, lockdown did not make me feel creative or productive. It made me anxious and enervated. Indeed, for two months I think I barely touched the piano….” Ultimately, producer and friend Adam Abeshouse convinced Dinnerstein to document her acclaimed interpretations of Glass & Schubert.

While engineered in Brooklyn, the recording encapsulates well the quiet of a small room. Stripping away the trappings of long reverb tails found in concert spaces and the omnipresent noise floor of creaking chairs and rustling listeners in a live recording, the isolated recording presentation is both austere and appropriate. It is a rare and wonderful opportunity to be able to hear an unadorned sonic performance—the depress of each key, the deliberate hesitations and miniscule breaks in chords that add longing to Schubert and humanize the often mechanically-performed Glass.

With the unique recording setting and circumstances, it is interesting to hear these works and reassess their impact on the listener. Of the three Glass Etudes present on the record, perhaps the opening track Etude 16 is most effectively served by the dry yet intimate space. Here the slight variations with each repetition are carefully spun, the rubato guiding the listener through harmonic shifts and liquid color undulations. The 30 seconds of true forte suitably ring out, before relaxing to a more enveloping warmth that gradually fades with utmost control back to the murky opening material. In true Glass fashion the ending lingers for an extra minute, leading the audience at home to contemplate their own quiet listening spaces.

Occasionally the moments of bombast in the other Etudes are mildly hampered by the lack of a kindly resonating hall space. Also, at climactic moments one may miss the physical presence of a full concert grand, with the tactile low end that can be felt in the bones. Yet the breathless clarity of the pristine runs in Etude 6 and the masterful pacing of the minutes-long crescendo in Etude 2, both without reverb to muddy the ears, is a worthwhile tradeoff. In all, one gains a new appreciation for the touch required at the instrument to execute these pieces.

In contrast, the Schubert Sonata in B-Flat Major D. 960, pulls the mics back a little more into the space for a more traditional stance on recording, as well as adding more of a gentle producer’s touch with a hint of extra reverb (unless Brooklyn is home to airier spaces than I realize). This contrast in recording style within a single album is a surprise at first listen but makes for an enjoyable duality to contrast the two composers. Clocking in over 40 minutes, this mammoth work, Schubert’s final sonata for piano, is well-served with a touch more added shimmering resonance anyway, and it is a light enough addition to feel organic throughout.

The opening movement is a journey unto itself, and Dimmerstein’s execution of the gradual rhythmic diminution and augmentation of the texture as the energy ebbs and flows is masterful. The chorale sections feel placid without lacking phrasing and direction, while the frenetic moments for the left hand are wonderfully driving without sounding uncontrolled. With a near 5-minute exposition, it is all too easy to give in to wandering lines, a problem only compounded by an enormous development. Dimmerstein’s approach to the pivotal d minor arrival is less explosive than Richter or Kovacevich, but maintains the character of Schubert, even in his late stages of composition; in a respectful way the interpretation is similar to Brendel.

The patient Andante second movement is given warmth in the home recording, while the third movement’s Scherzo is as exciting as always, even at a less than blazing fast tempo. Again, the closer recording setup gives cleanly executed passages a brilliance that makes for an energized listening experience. The dynamic peaks of the final Allegro movement are a fuller grandiose sound than heard anywhere else in the piece, which only better serves to make the subito shifts in character and texture that much more of a playful romp with its own ten minute run time flying by with vitality in contrast to Schubert’s failing health at the time of composition.

Simone Dimmerstein may have been reluctant to dive into a project such as this, but listeners will be enraptured by the result. Recording any of Schubert’s final sonatas is no dalliance to take on lightly and pacing out Glass’s etudes is a focused exercise no matter the situation. As Dimmerstein releases her thoughtful interpretations of these pieces into the world, the constraints of this recording project elevate the music rather than distract, providing a worthwhile listen of fresh sounds for audiences’ ears.

Please leave comments or questions below!

From Navona Records:

Liza Stepanova’s ‘E Pluribus Unum’

Pianist Liza Stepanova’s August 28th release E Pluribus Unum on Navona Records is described on her website as “Born out of the political climate of 2017” and “an artistic response to the immigration policies implemented by the American government at that time.” These issues that began to emerge over three years ago in 2017 are still present today, making this release remarkably timely. Though the specific works may thematically tackle issues of immigration or social inequality, “above all, the music on this album reflects the composers’ roots, celebrates their immense contributions to American musical life, and a confluence of voices, narratives, and ideals.” In this way the album acts as a thoughtful commentary on the hyper partisanship currently occupying our national political landscape – almost an artistic embodiment of the concept when they go low, we go high.

Stepanova’s commitment to highlighting a diversity of influence and her advocacy for new music is evident, as the release features three world premiere recordings including a commissioned piece from emerging composer Badie Khaleghian. In addition to the premiere recordings, the majority of the works were composed within the last 10 years.

A selection from Lera Auerbach’s Scenes from Childhood – An Old Photograph from the Grandparents’ Childhood begins the album. The movement is plaintive, and acts as a fitting prelude. Its melody is gently coaxed into a character of lyrical nostalgia by Stepanova’s phrasing – inviting a sense of intimacy and promise.

Kamran Ince’s Symphony in Blue (titled after a Burhan Dogancay painting, and commissioned by the Istanbul Modern Museum in honor of its showing) follows Auerbach’s work. Ince’s piece requires a careful control of sonic decay, allowing dense blocks of sound to give way to initially muted percussive echoes and eventual bombastic exclamations. Stepanova navigates these shifts with grace – always mindful of the thematic importance of decay even within the work’s busier textures.

This kind of musical sensitivity is also featured in two of the world premiere recordings included on the release, Eun Young Lee’s Mool and Chaya Czernowin’s fardanceCLOSE. Eun Young Lee describes her piece as being associated with water – specifically the use of shifting tone color to reflect the changes of character within the water cycle. Czernowin’s fardanceCLOSE likewise requires a careful control of clarity of line through registral shifts and a gradual escalation of the relentless repeated gesture that ends the work. In both instances, Stepanova has obviously lived with these works long enough to subtly manage these changes of character in a convincing organic manner.

Stepanova’s technique throughout is polished and assured. Her facility at the keyboard realizes the driving rhythm of Reinaldo Moya’s IV La Bestia, and the blistering passages in Anna Clyne’s On Track with surgical precision. Though the technical fireworks are impressive, Stepanova’s articulation truly stands out. The precise articulation and touch heard in the swelling quasi bisbigliando gesture that opens the third movement of Badie Khaleghian’s Táhirih The Pure (both a premiere recording and a commission) is both crisp and fluid, and but one example of the intense attention to musical detail Stepanova brings to each work.

The album closes with Piglia by Pablo Ortiz and Gabriela Lena Frank’s Karnavalito No. 1. Ortiz’s work is written as an homage to the author Ricardo Piglia, and after a wandering introduction it settles into what the composer describes as a “relentless milonga pattern showing the kind of intense passion normally associated with the tango.” For me, the ending was spot on – a slight fading away leading to an upward gesture reminiscent of an incomplete question – and Gabriela Lena Frank’s work serves as a fitting answer and closing work for the album. According to the composer the piece “is inspired by the Andean concept of mestizaje . . . whereby cultures can co-exist without one subjugating another.” The piece provides Stepanova a chance to once again dazzle the listener with virtuosic precision, and the slightly puckish ending provides a sound thematic and musical conclusion to the album.

This album warrants attention on its musicality alone. But, I am also drawn to it for its quiet insistence that music (as is true with most things) is best as a shared experience that makes a space for all. I’ll be seeking out more music by the composers featured on this release, and I look forward to the new music that partnerships with engaging performers like Liza Stepanova will continue to produce.

Leave Comments Below!

New Release from Iceland

Gyða Valtýsdóttir (Epicycle II), release date August 28th on DiaMond/Sono Luminus

Gyða Valtýsdóttir first appeared on the scene as a member of the group múm, an experimental electronic Icelandic group, whose second album, Finally We Are No One (2002) reached as high as Number 16 on the UK Independent Album chart. She then left the band to go to conservatory to pursue her studies as a cellist; earning a Master’s degree from Musik Akademie, Basel, in the increasingly popular dual degree of area of classical performance and free-improvisation. After a period of years touring and collaborating with the classical and electronic stars of Iceland’s musical sky, and obviously informed by her studies in Basel, she released Epicycle (2017), a compilation of interpretations of some of the greatest works in in the Western Canon. From Harry Partch’s Ancient Mode to Robert Schumann’s “Im Wunderschönen Monat Mai” the selections are pieces that are well known to most Music History teachers as strong pedagogical tools, the strength of Valtýsdóttir’s work is that she revives this music in a modern context.

This summer, on August 28th, she is set to release a sequel, Epicycle II which is composed of works by Iceland’s top notch contemporary composers. As she describes it: “This time I wanted to collaborate with contemporary composers and musicians who have each created their own, unique musical language that doesn’t fall easily into any existing category.” In the tradition of Russia’s “Mighty Handful” or France’s “Les Six” the result is a kind of “Icelandic Eight” or perhaps better “þeir átta,” a coherent documentation of the Icelandic school of composition in the second decade of the 21st Century–and it sparkles with moments of genius. From atmospheric micro-polyphony to heart-rending moments of electronic intimacy, the music is interesting and powerfully drawn.

The CD begins with Unfold by Skúli Sverrisson, an composer and bass guitarist who has won five Icelandic Music Awards, including Album of the year. The track, as predicted, unfolds in a paced mesmerizing development of a single theme with parallel lines in distant registers, implying an underlying (or overlying) polyphony that is just this side of perceptible. Perhaps it is this sonic reflection of the primary melody that Valtýsdóttir is referring to when she describes playing the track as “like dancing in the prism of its light.” The effect is discomforting in a hypnotic way, Mahlerian only in the way it creates a world apart.

Safe to Love was composed by Ólöf Arnalds and bridges the song and lieder tradition with an accompaniment drawn from ValtýsdóttiIcr’s pizzicato cello and serving as counterpoint to her airy, whispering, yet echoed voice. The intimacy in Jónsi’s mixing creates echos to seem to scatter into time and space. Anna Thorvaldsdóttir’s Mikros, is a rushing counterpoint on cello, is brief and disturbing in it’s extended techniques. It seems to channel George Crumb, think “La luna está muerta” or “Vox Balaenae.” Úlfur Hansson’s Morphogenesis evokes a similar “otherworldness” bringing precomposed string arrangements into concert with a custom built analog synthesizer and Valtýsdóttir’s improvisation.

Liquidity is the result of a collaboration with Kjartan Sveinsson at the Berlin Festival for the People in 2019. It is probably the most likely to succeed on the pop charts, sounding as if it were ripped from an epic historical fiction soundtrack, lending itself to some derived form of primal primitivism, yet there is interest in the way it coalesces around a repeated theme in the piano that is both memorable and purposefully incomplete in its many variations. Air to Breath was released by Daníel Bjarnason a decade ago, but it seems tailored perfectly for Valtýsdóttir’s nuanced, supple and warm cello. On an album of mostly premieres, one can understand why Valtýsdóttir included this track as the exception. Jónsi’s Evol Lamina might just be the most interesting track on the collection, a creation from sampled improvisations that borders on Musique concrète, but the samples are brought alive, even humanized by their delicacy in the upper registers as an unrecognizable, sampled bass pursues. The end is abrupt, like a book set down, halfway through the denouement. The last piece, Octo by María Huld Markan Sigfúsdóttir, is another essay on a brief motive, set into counterpoint with Valtýsdóttir extended harmonics. The dizzying variations of the theme suggest an inwardness that is at least uncanny and at most, transcendent.

Iceland arrived on the classical music scene quite late, with the first real concerts only occurring in the early 20th Century. Their first real virtuoso, Ashkenazy, was a Soviet defector. However, they have been actively working to catch up. I wouldn’t be so silly and foundational as to propose an “Icelandic style” that unites them in an intrinsic nationalistic character, but I will propose that it is a burgeoning school around which principles of developing variation, extended techniques and experimental timbres are united into a subtle polyphony of conscious and subconscious aesthetics. Of course the sound is also postmodern, a collage that can be romanticized, as it is in Safe to Love or endowed with expressionistic modernism as in Evol Lamina. In either case, it is interesting, will likely be influential as the various members of þeir átta develop, but most of all worth your time and attention.

Please leave comments below!

Hope from the Nashville Opera

Can You Imagine a Beach-Party Themed Cinderella Next June? Nashville Opera can!

In the most wonderful sense of optimism and a little more than a decent dose of stubbornness, Nashville Opera has released their schedule for next season, a celebration of their 40th anniversary and it looks to be a doozy!

One Vote One

The season opens on September 25-27 with a commission, N.O.’s first, in a performance of the election day drama One Vote One with music composed by Tennessee native

David Ragland and the libretto by Mary McCallum. Originally hailing from Chattanooga, Ragland has been on the Nashville scene for some time now, I first heard his music in his beautiful arrangement of spirituals at the Upon these Shoulders celebration at Fisk University in 2017, and he made his directorial debut with the Nashville Opera during the 2013-14 season in their production of David Lang’s “The Difficulty of Crossing a Field.” His Steal Away was originally scheduled with Oz Arts in April, but had to be cancelled because of COVID19. McCallum, who has written for stage and screen including Singleville (2018) and the fictional historical play Six Triple Eight (2015), is a wise choice for the libretto.

These two artists will be able to share their talents for historical depiction in One Vote One with a plot that includes suffragist Frankie Pierce (played by Jennifer Whitcomb-Oliva) and Civil Rights activist Diane Nash (played by Brooke Leigh Davis) as they work to convince a young Gloria (played by Tamica Nicole Harris) that her vote counts.. Never an organization to shy away from a political topic, Director John Hoomes and company are working with the MTSU Center for Historic Preservation to create a study guide that meets Tennessee standards for U.S. history.

Opera Jukebox

In October, the company will present the newest in pandemic operatic genres, the “Opera Jukebox.” Not much to say here except that money talks and I hope the rich folks seek to hear something other than the same old chestnuts like “Nessun Dorma,” “L’amour est un oiseau rebelle'” or the flower duet.

Rigoletto

Then in April, if one can imagine the end of the pandemic, the return of our economy, and a post-election 2020 world, the company has scheduled a new staging of

Verdi’s Rigoletto in a film noir style. Likely to be the highlight of the artistic season in Music City (ok, so maybe there wont be much competition) the staging will include its own original film noir by Penumbra Entertainment, winner of the Nashville Opera Noir Filmfest. However, the cast is quite exciting too; as Nashville Opera describes the production: “The wise-cracking Rigoletto (Michael Mayes), despised by all save his beautiful daughter (soprano Kathryn Lewek in her first appearance as Gilda), is powerless to protect her from the lechery of his boss, Duke (Zach Borichevsky also making his role debut).” Notably, the production was initially planned for last season but the world stopped. From Lewek’s facebook of March 16th, 2020:

My husband Zach Borichevsky, tenor and I are disappointed about the cancellation of Nashville Opera’s production of Rigoletto in which we were to make our role debuts as Duke and Gilda, respectively. However, we are so grateful to the company, as they are paying us a portion of our contract. It’s amazing to see regional companies like Nashville, led by John Hoomes, set the example for other companies. We have just donated a part of our earnings to the AGMA (American Guild of Musical Artists) artist relief fund. I hope all who have the means to make a small or large donation will consider…”

Cinderella

More than half of businesses that closed during the pandemic won’t reopen

The reviews site has been keeping tabs on closures since March. Businesses can update their status to temporarily or permanently closed on Yelp.

As of August 31, nearly 163,700 businesses on Yelp have closed since March 1, the company said, marking a 23% increase from July 10. Of those, about 98,000 say they’ve shut their doors for good.

Of all closed businesses, about 32,100 are restaurants, and close to 19,600, or about 61%, have closed permanently.

Read More

Comment Below!

Comment Below!

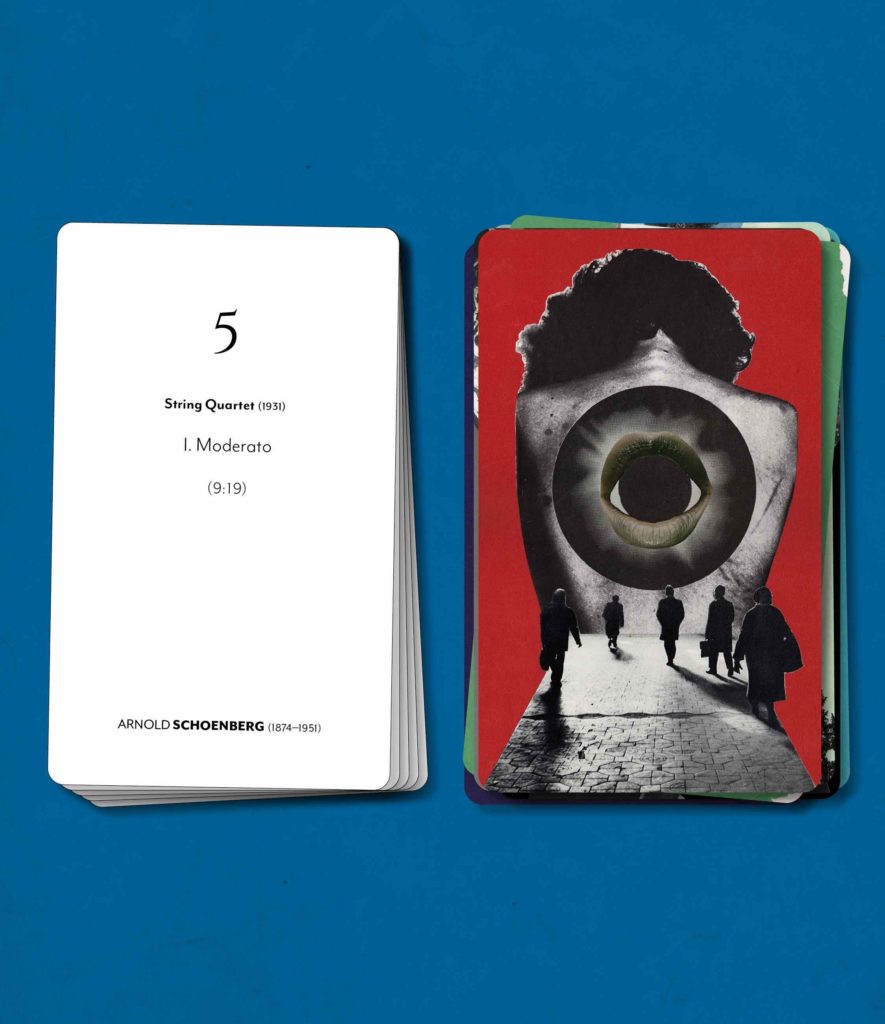

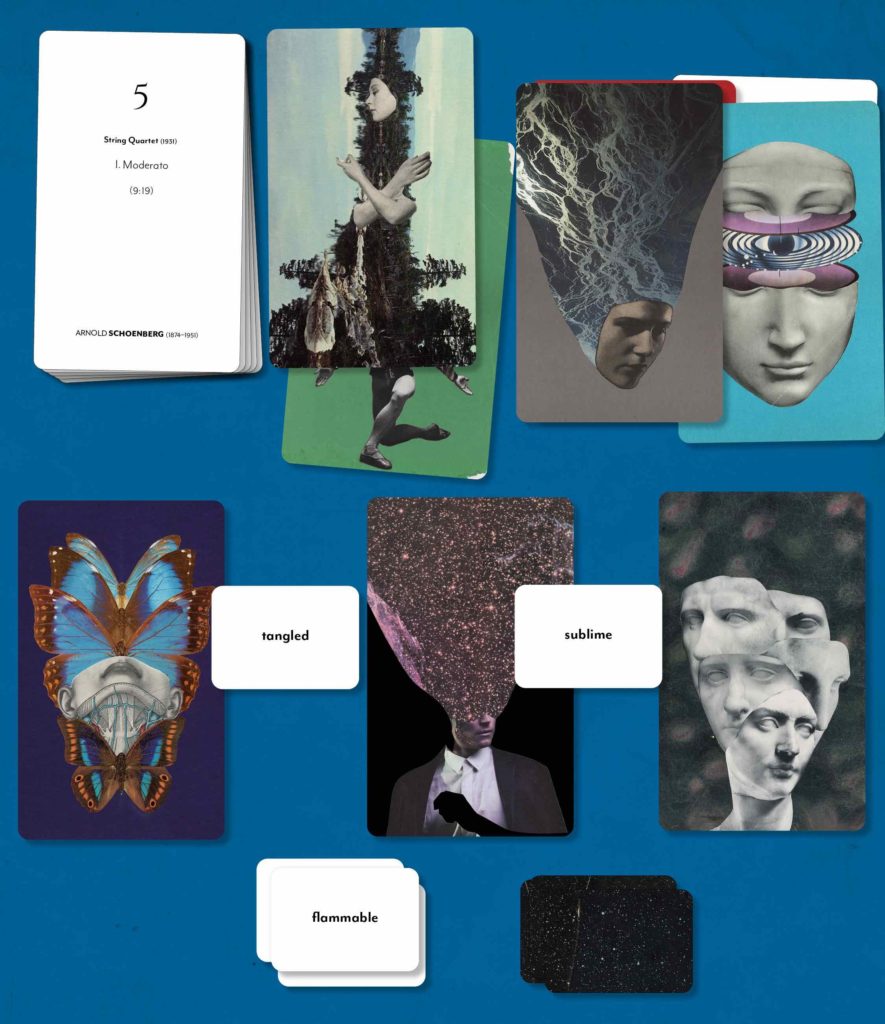

Three weeks after cancelling the 20/21 season, the Nashville Symphony released a new recording featuring the music of the Grammy and Pulitzer Prize winning composer Christopher Rouse. This recording, the 21st for the Nashville Symphony under Naxos’ American Classics label, is a welcome addition to the fruitful collaboration between the Nashville Symphony and American composers. This is the second installment of a trio of recordings to be released this summer: Aaron Jay Kernis’

Three weeks after cancelling the 20/21 season, the Nashville Symphony released a new recording featuring the music of the Grammy and Pulitzer Prize winning composer Christopher Rouse. This recording, the 21st for the Nashville Symphony under Naxos’ American Classics label, is a welcome addition to the fruitful collaboration between the Nashville Symphony and American composers. This is the second installment of a trio of recordings to be released this summer: Aaron Jay Kernis’

The Nashville Symphony just released it’s newest recording on Naxos’s American Classics series. Featuring two works by Pulitzer, Grammy and Grawemeyer Award winning composer Aaron Jay Kernis, Color Wheel (2001) and Symphony No. 4 ‘Chromelodeon (2018), this recording will complement well the Symphony’s already extensive collection of contemporary music recordings (listed here:

The Nashville Symphony just released it’s newest recording on Naxos’s American Classics series. Featuring two works by Pulitzer, Grammy and Grawemeyer Award winning composer Aaron Jay Kernis, Color Wheel (2001) and Symphony No. 4 ‘Chromelodeon (2018), this recording will complement well the Symphony’s already extensive collection of contemporary music recordings (listed here: