Live on the Internet:

Orpheus Chamber Orchestra performs Beethoven’s Egmont

Initially, one may ponder if Ludwig van Beethoven’s 250th birthday really needs to be celebrated with performances offered in his memory. Does extra attention need paid to a composer who is canonized every year, throughout the world, in various genres? Should programming instead attempt to draw relevant parallels to current events in hopes of providing some insight and reflection about modern conflicts? Fortunately for us, the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra has managed to do both with their most-recent production of Egmont, Op. 84.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s 1788 play, Egmont, has been adapted by Franz Grillparzer, with an English translation and further adaptions made by Philip Boehm for this production. Action centers around Count Egmont’s martyrdom in protest of the occupying forces under the command of the Spanish invader, the Duke of Alba. Championing the ideals of liberty and justice, Egmont’s death is celebrated as a victory against oppression. Beethoven composed a series of incidental music movements between October 1809 – June 1810 to enhance Goethe’s text. This music was written shortly after Beethoven had completed his Fifth Symphony – a time when both the Napoleonic Wars and Beethoven’s political views were raging.

…a time when both the Napoleonic Wars and Beethoven’s political views were raging.

It may seem puzzling for a revolutionary like Beethoven to collaborate with a courtier like Goethe. Perhaps, but despite their different sociopolitical leanings, there remained a mutual respect amongst the two creative geniuses for each other’s work – an impressive siloed restraint of bipartisanship. Equally impressive is the recent performance of this work by the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra. Filmed on October 1 at the Beechwood Park Bandshell in Hillsdale, New Jersey, the performance is available for viewing from October 17-22 via the Idagio platform online.

The musicians were seated with a degree of social distancing between every performer. String and percussion forces remained masked the entire performance, whereas woodwind and brass musicians did not use masks or any form of instrument coverings. Narrator, Liev Schreiber, and vocal soloist, Karen Slack, removed their masks just before their respective first contribution to the performance, never again using facial coverings for the remainder of the work.

The Orpheus Chamber Orchestra programmed Tarkmann’s arrangement of Egmont. This setting uses reduced orchestral forces, specifically a single flute – doubling on piccolo, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, trumpet, and one percussionist, in addition to the expected string consort compliment. While effective, some density of the original composition is lost with omitted octaves in lieu of a more transparent harmonic texture.

Liev Schreiber’s enchanting vocal cadence effectively captures focus from the beginning. The varied use of inflection and pacing successfully helps to navigate one through a complex network of emotion. Schreiber’s opening dialogue delivers a hauntingly familiar sentiment for those frustrated with the current political climate, offering the belief that, “. . . but in their hearts, they are yearning for the past.” This desire for a more ideal time is obstructed by our antagonist, the Duke of Alba, who’s objective is to, “quash dissent.” Yet another familiar political tweeting muse. The exchange between the musicians and the narrator has been finely tuned and proves to be a welcomed retreat from the noise of other interrupting facets of modern life.

Not to be forgotten is Karen Slack. Ms. Slack is a seasoned performer whose stage presence and vocal command is inspiring. The two vocal movements, “Die Trommel gerühret” and “Freudvoll und leidvoll,” leave one wishing that this work included additional movements that would feature her voice. Slack currently has a busy artistic season scheduled, of which a world premiere by Adolphus Halistork is rather intriguing. Aspiring to achieve such truth through performance as Slack does, makes ‘being a Karen’ no longer a pejorative.

The third incidental music setting, “Entracte: Andante,” was highlighted by Eric Reed’s horn playing. The agility used to reach the highest of registers proved to be impressively controlled. Leading into the sixth setting, Goethe offers that, “What words can’t tell, music will convey.” James Austin Smith’s oboe playing then certainly requires multiple volumes. The cantabile quality achieved by Smith throughout “Entracte: Allegro-Marcia” was paired with a clarity of articulation and a convincing ability to prepare cadential moments that, in turn, felt inevitable. Maya Gunji’s timpani playing further enhanced the performance later in this same movement, contributing an assured and unyielding depiction of the passing time.

Gunji’s playing later gives way to the lyrical ‘mezza voce’ mourning of clarinetist Alan Kay in the next setting, “Entracte: Poco sostenuto e risoluto.” Kay’s moving contribution is a deployment exquisitely supported by Gina Cuffari on bassoon. Elizabeth Mann’s flute playing enhances the penultimate movement, “Melodram: ‘Süßer Schlaf,’ before Louis Hanzlik’s trumpet playing courageously heralds “Siegessymphonie: Allegro con brio” and encourages the ensemble to energetically reach the conclusion.

Various camera angles and musically driven editing keeps one’s interest while still maintaining focus on the composition. Some ambient noises can be heard, and, on a few occasions, camera angles include a parking lot in the background of some shots. While the two aforementioned realities are noticeable, I would stop well short of suggesting that they are distracting. I have yet to attend a live concert where the unspoken compromise of undesired audience participation – coughing, dropped programs, loud whispering, et. al – is not willingly waged for the chance to experience the magic inherent with live performance. I would suggest ‘going all in’ to view this production.

With recent notices signaling the cancellation of seasons by the Metropolitan Opera, New York Philharmonic, and Broadway, the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra should be commended for its willingness to adapt and find flexible solutions to continue safely creating art. This performance of Beethoven’s Egmont, Op. 84, feels to exist in the vernacular of society’s current struggle to define its desired trajectory of morality. Our desire to define our North Star, be it rising stock markets, law and order, an empathetic awareness that we can only be as strong as our weakest member, or a combination thereof, has been brilliantly mirrored through this performance.

Nashville Opera

One Vote Won: A Streaming Must-See

Ask anyone from six months ago what they’d be doing right about now, and I’m sure it would be far different from what we’re pulling off now. For musicians, composers, actors and actresses, artists, and admin, this current cycle in the thing we call life is a weary one. Couple this reality with tense race relations and ever-increasing inequity, and it’s as if the world may never recover. While many seek a return to the status quo, the Nashville Opera is taking a different approach. With One Vote Won, the company is rightfully meeting the moment we face as a society. Composed of diverse musicians and a cast that encompasses some of the best talents in Music City, with varying musical excellence and acting to boot, the virtual premiere of this work by composer Dave Ragland is significant. This year has brought lots of surprises, for better or for worse. That said, this premiere is the best surprise to rise from the ashes of 2020. Composed by Dave Ragland with a libretto by Mary McCallum, One Vote Won is a work that brings together a brilliant Nashville cast in a unique and inspiring way.

The opera begins by introducing us to Gloria (Tamica Nicole), a contemporary woman whose character we gradually become familiar with as the work progresses. A sharp mix of humor, wit, and powerful composition, the beginning introduces us to Gloria’s world, as well as her thinking. She’s discouraged with the state of things, and frankly, who isn’t these days? We see a character that strays from the prima donna we’re used to seeing in many operas. But what’s unique about Gloria is that very fact – she’s relatable, funny, and Tamica Nicole flawlessly encapsulates this personality through incredible prose. From the impressive leaps and overall melodrama, Gloria is a character with dazzling range and passion (for Disney+ and Hulu, that is).

“People sleeping in the streets” begins our next sequence, as Gloria takes a walk to clear her head but can’t keep from focusing on these stark truths in plain sight. A reality that one would think was from the pen of a composer in less fair and less equal times. Gloria is one that Ragland and McCallum can paint so eloquently – a woman who is independent and questions so firmly the possibility of change. 2020 is a year when it’s easier than ever to become demoralized. But just as we look back on Mozart and Beethoven to conjure a picture of the hardships they lived, so future generations will too with works like One Vote Won. Will we confront the past and change for the better? Gloria isn’t convinced, and as these opening scenes in particular point out, change is long overdue.

As the story continues, we also become familiar with two titans of progress. These two women are having a field day in Gloria’s mind, as she fails to block them out as they shout, “go vote!” The identity of one of these hidden figures is then revealed as Juno Frankie Pierce, played by the incredible Jennifer Whitcomb-Oliva. Frankie Pierce, born to a house slave, was the only African American to address the May 1920 state suffrage convention held in the Tennessee House chamber, and ultimately was the founder of the Tennessee Vocational School for Colored Girls. Whitcomb-Oliva brings life to Frankie Pierce in a way that urgently recounts her history. “What if one woman decided not to vote?” Pierce pleads her case to Gloria. The range and dictation in the two character’s recitative as Frankie Pierce plays devil’s advocate is flawlessly executed, even with the actors and musicians not filming together for social distancing purposes. Gloria exclaims that even years later, we’re still fighting, and she keeps pressing the fact that her voice doesn’t matter. Again, the opera focuses on subject matter that can feel close to home for so many. There are pronounced nuances to the composition in-turn, such as how the libretto carefully intermingles with the tone-poem style playing of the stripped-down orchestra.

Despite Pierce recounting her history to no avail, the audience then discovers the second voice in Gloria’s head. Diane Nash, portrayed by Nashville’s own Brooke Leigh Davis, was a crucial figure in the civil rights and antiwar movements from 1959 to 1967. She was instrumental in the desegregation of Nashville’s lunch counters and also heavily involved with Martin Luther King Jr.’s peaceful protests as well as the Freedom Rides. Most notably, Nash is still alive today, a sheer reminder of how close this history still is to our modern times. The biggest challenge of acting a character that is still alive and making it a success is all about the authenticity and realness you can bring to them. As with the rest of the cast, Leigh Davis is a mighty singer and is not ashamed to hold back, ultimately providing that much more interest and color to this work as a whole. An important quality, especially for an opera that cannot premiere in person. While Nash is still from a different era than our contemporary Gloria, the viewer can tell that Nash is still just as relevant today as she was then. Nash paints her history with a brush that consists of dynamic vocals accompanied by intense passages performed by musicians Shelly Blair, Cremaine Booker, and Konson Patton.

The scene briskly pivots to tell of how Nash proudly led many Nashville sit-ins and ultimately confronted the local mayor, Ben West, to convince him to desegregate lunch counters. Still, even Nash’s bravery and sacrifice told through intriguing cut-scenes offer no success. In spite of Pierce and Nash being ghastly opposed to Gloria’s thinking, Ragland is still able to open a window and intrinsically show why she feels this discouragement. This sentiment felt, frankly, by many African Americans across the United States. “To be oppressed, you have to agree,” exclaims Nash, right before the audience is whisked again into one of the most powerful and arguably most musically fascinating scenes of the work.

The last few minutes shift to a tour-de-force of all three women contending with jazzy undertones and the most epic libretto of the piece. At last, Gloria’s tone has changed. As she recites the names of black people that have died at the hands of police violence, she ultimately convinces herself that the change that’s needed is too crucial and not worth dismissing. Through the scenes prior and with a final beautiful duet, Frankie and Diane show Gloria how change can happen through many different means, and ultimately her vote is a good start.

As arts organizations across the country and the world reckon with a past that has excluded and marginalized certain groups, it is new and relevant works such as One Vote Won that is needed more than ever. Despite all of its faults, art has a history of adaptation that progresses because of this age-old notion of creating new and meaningful things that impact our lives. That said, recording and streaming an opera that is live-sung is no easy feat. Streaming, of course, also brings with it a multitude of technicalities that could further alienate viewers. Nevertheless, seasoned Nashville Opera listeners expect this forward-thinking attitude from the company. But it begs the question, will the opera reach its intended audience that it means to persuade? Is this the sign of an industry that’s ready to change and confront its past while moving towards a brighter future that is more inclusive and aware? One Vote Won is smart, epic, and meets the moment in a way unique to Nashville Opera. “It’s time to make a change” ends the piece. Indeed time will tell what the future brings, but as Dave Ragland’s incredible work points out, change starts with you. And me. And them.

Subscribe, Comment or Share below!

Live Music in Nashville

Nashville Composer Collective at Asaph’s Chamber

This past Sunday afternoon (September 20th) the Nashville Composer Collective (NCC) put on their 22nd program in Belmont University’s intimate Asaph’s Chamber. Chairs were spread out out throughout the space either alone or in pairs and accommodated about 25 audience members. The concert, lasting barely under an hour, was an unpretentious presentation of six varying works and resulted in six individual successes. Personally, I was tremendously excited for this performance as it was the first live music event I have attended in over half a year.

John Darnall, Director of the NCC, introduced each piece and its’ composer, offering them the opportunity to say a few words about their work. First up was Melanie Alvey with her piece Mountain Echoes orchestrated for three violins (one electrically amplified and hooked up to a looping station), viola, cello, and electric bass. Opening with a solo violin creating a multi layered loop of an asymmetric groove, gradually the rest of the ensemble comes in building on the established beat. This piece was pleasing both aurally and visually seeing the opposing violins echoing gracefully back and forth to each other over the ostinato. Mountain Echoes was a personal favorite of mine on the concert and it is always a treat to see the composer performing their own work.

Up next was Jack Williams’ Emergence for string quartet. Steeped in 20th century compositional techniques, Emergence is a mature piece that gripped me from the start. Quartal and quintal harmonies mix with contrapuntal techniques, motives bounce around the ensemble, and lyrical melodies are contrasted with jagged sections. Although there was much going on throughout the piece, one never lost their way and could easily follow the logic of the piece.

After two string ensembles the concert moved to Joodils by Andre Madatian for flute and piano. Translated from Armenian, Joodils means “Little Bird.” This work was written for his Grandmother who recently passed and who always enjoyed bird song. The flute, depicting the bird calls, was complemented with the supportive harmonies of Nathan Girard at the piano who occasionally also echoed some of the bird calls. Special appreciation should be given to Jess Benevento on the flute, who tackled the virtuosic flute part with great poise and fantastic technique. Overall Joodils was a great joyful piece that is a fantastic memorial to Andre’s grandmother’s memory.

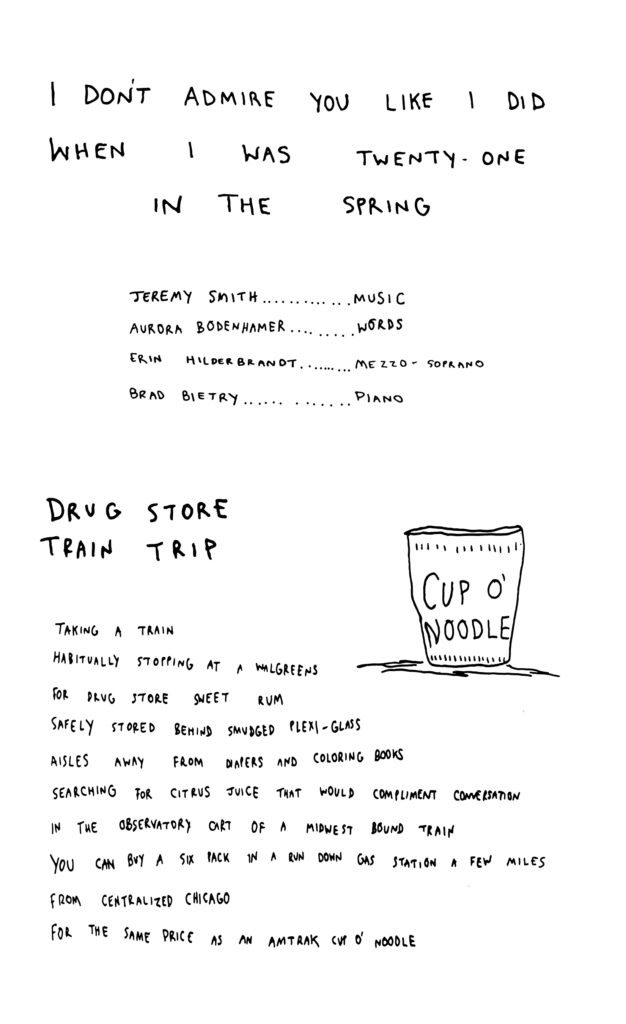

Beginning the second portion of the event was Jeremy Smith’s song cycle I Don’t Admire You Like I Did When I was 21 In the Spring. This included three short songs: Drug Store Train Trip, Jersey, and Your Apartment in Soho. Jeremy set the words of Aurora Bodenhamer, a poet who he found on Instagram (and also did the hand drawn cartoons for the accompanying lyric sheet). Erin Hildebrandt, sang her way beautifully through the score which was filled with tricky harmonic intervals and impressive leaps. The music was thickly set to the rather unassuming poems, and Jeremy was able to draw out the humor and color of the words.

Kyle Baker’s Divertimenti for Clarinet and Piano was up next. This was a beautiful piece that featured the clarinet, played brilliantly by Raymond Ridley. Melodies led the piece from one section to the next with the clarinet usually taking the lead. It was solidly constructed and would make for a great repertoire piece for any clarinetist. My one complaint is that we were only treated to the first movement, entitled Wandering.

Ending the program was the first movement of John Darnall’s “String Quartet #1” that he was recently commissioned to write. Similar to the other quartet on the program, this piece drew inspiration from 20th century techniques, and John masterfully infused them with his own colors and ideas. Of particular interest to me was the wonderful treatment of the pizzicato within the piece. Sometimes it served as an accompaniment to other melodies, and in differing places it was a technique featured throughout the entire ensemble.

The concert was a great success for each of the composers and the whole Nashville Composer Collective ensemble. It is always a treat to hear new music, and especially so when the composer is still alive and able to talk to you about their work. I look forward to attending many more concerts and supporting the NCC in all that they do, and I would encourage anyone reading to support the ensemble.

Add comments or questions below!

A New Release from Orange Mountain Music

From the Intimacy of Quarantine, Simone Dinnerstein’s “A Character of Quiet”

The tumult of 2020 has brought trials and tribulations to all, but as people discover silver linings in enjoying more time at home or taking up a new hobby to pass the time, the fall looks to bring fruits of artists’ labors. With tours cancelled and performances postponed, musicians’ “quarantine albums” and projects have been churning out across all genres as the summer has passed, with no sign of this trend slowing. American pianist Simone Dinnerstein’s contribution “A Character of Quiet” offers an intimate home recording, pairing Philip Glass and Franz Schubert to great effect.

Being cooped up obviously affects people in different ways. While a restless energy may translate to productivity and inspirational focus for some, others may struggle with the suspension of routine and stagnant scenery at home. When preparing for this project, Dinnerstein notes her own struggles with the situation, bluntly speaking how “candidly, lockdown did not make me feel creative or productive. It made me anxious and enervated. Indeed, for two months I think I barely touched the piano….” Ultimately, producer and friend Adam Abeshouse convinced Dinnerstein to document her acclaimed interpretations of Glass & Schubert.

While engineered in Brooklyn, the recording encapsulates well the quiet of a small room. Stripping away the trappings of long reverb tails found in concert spaces and the omnipresent noise floor of creaking chairs and rustling listeners in a live recording, the isolated recording presentation is both austere and appropriate. It is a rare and wonderful opportunity to be able to hear an unadorned sonic performance—the depress of each key, the deliberate hesitations and miniscule breaks in chords that add longing to Schubert and humanize the often mechanically-performed Glass.

With the unique recording setting and circumstances, it is interesting to hear these works and reassess their impact on the listener. Of the three Glass Etudes present on the record, perhaps the opening track Etude 16 is most effectively served by the dry yet intimate space. Here the slight variations with each repetition are carefully spun, the rubato guiding the listener through harmonic shifts and liquid color undulations. The 30 seconds of true forte suitably ring out, before relaxing to a more enveloping warmth that gradually fades with utmost control back to the murky opening material. In true Glass fashion the ending lingers for an extra minute, leading the audience at home to contemplate their own quiet listening spaces.

Occasionally the moments of bombast in the other Etudes are mildly hampered by the lack of a kindly resonating hall space. Also, at climactic moments one may miss the physical presence of a full concert grand, with the tactile low end that can be felt in the bones. Yet the breathless clarity of the pristine runs in Etude 6 and the masterful pacing of the minutes-long crescendo in Etude 2, both without reverb to muddy the ears, is a worthwhile tradeoff. In all, one gains a new appreciation for the touch required at the instrument to execute these pieces.

In contrast, the Schubert Sonata in B-Flat Major D. 960, pulls the mics back a little more into the space for a more traditional stance on recording, as well as adding more of a gentle producer’s touch with a hint of extra reverb (unless Brooklyn is home to airier spaces than I realize). This contrast in recording style within a single album is a surprise at first listen but makes for an enjoyable duality to contrast the two composers. Clocking in over 40 minutes, this mammoth work, Schubert’s final sonata for piano, is well-served with a touch more added shimmering resonance anyway, and it is a light enough addition to feel organic throughout.

The opening movement is a journey unto itself, and Dimmerstein’s execution of the gradual rhythmic diminution and augmentation of the texture as the energy ebbs and flows is masterful. The chorale sections feel placid without lacking phrasing and direction, while the frenetic moments for the left hand are wonderfully driving without sounding uncontrolled. With a near 5-minute exposition, it is all too easy to give in to wandering lines, a problem only compounded by an enormous development. Dimmerstein’s approach to the pivotal d minor arrival is less explosive than Richter or Kovacevich, but maintains the character of Schubert, even in his late stages of composition; in a respectful way the interpretation is similar to Brendel.

The patient Andante second movement is given warmth in the home recording, while the third movement’s Scherzo is as exciting as always, even at a less than blazing fast tempo. Again, the closer recording setup gives cleanly executed passages a brilliance that makes for an energized listening experience. The dynamic peaks of the final Allegro movement are a fuller grandiose sound than heard anywhere else in the piece, which only better serves to make the subito shifts in character and texture that much more of a playful romp with its own ten minute run time flying by with vitality in contrast to Schubert’s failing health at the time of composition.

Simone Dimmerstein may have been reluctant to dive into a project such as this, but listeners will be enraptured by the result. Recording any of Schubert’s final sonatas is no dalliance to take on lightly and pacing out Glass’s etudes is a focused exercise no matter the situation. As Dimmerstein releases her thoughtful interpretations of these pieces into the world, the constraints of this recording project elevate the music rather than distract, providing a worthwhile listen of fresh sounds for audiences’ ears.

Please leave comments or questions below!

From Navona Records:

Liza Stepanova’s ‘E Pluribus Unum’

Pianist Liza Stepanova’s August 28th release E Pluribus Unum on Navona Records is described on her website as “Born out of the political climate of 2017” and “an artistic response to the immigration policies implemented by the American government at that time.” These issues that began to emerge over three years ago in 2017 are still present today, making this release remarkably timely. Though the specific works may thematically tackle issues of immigration or social inequality, “above all, the music on this album reflects the composers’ roots, celebrates their immense contributions to American musical life, and a confluence of voices, narratives, and ideals.” In this way the album acts as a thoughtful commentary on the hyper partisanship currently occupying our national political landscape – almost an artistic embodiment of the concept when they go low, we go high.

Stepanova’s commitment to highlighting a diversity of influence and her advocacy for new music is evident, as the release features three world premiere recordings including a commissioned piece from emerging composer Badie Khaleghian. In addition to the premiere recordings, the majority of the works were composed within the last 10 years.

A selection from Lera Auerbach’s Scenes from Childhood – An Old Photograph from the Grandparents’ Childhood begins the album. The movement is plaintive, and acts as a fitting prelude. Its melody is gently coaxed into a character of lyrical nostalgia by Stepanova’s phrasing – inviting a sense of intimacy and promise.

Kamran Ince’s Symphony in Blue (titled after a Burhan Dogancay painting, and commissioned by the Istanbul Modern Museum in honor of its showing) follows Auerbach’s work. Ince’s piece requires a careful control of sonic decay, allowing dense blocks of sound to give way to initially muted percussive echoes and eventual bombastic exclamations. Stepanova navigates these shifts with grace – always mindful of the thematic importance of decay even within the work’s busier textures.

This kind of musical sensitivity is also featured in two of the world premiere recordings included on the release, Eun Young Lee’s Mool and Chaya Czernowin’s fardanceCLOSE. Eun Young Lee describes her piece as being associated with water – specifically the use of shifting tone color to reflect the changes of character within the water cycle. Czernowin’s fardanceCLOSE likewise requires a careful control of clarity of line through registral shifts and a gradual escalation of the relentless repeated gesture that ends the work. In both instances, Stepanova has obviously lived with these works long enough to subtly manage these changes of character in a convincing organic manner.

Stepanova’s technique throughout is polished and assured. Her facility at the keyboard realizes the driving rhythm of Reinaldo Moya’s IV La Bestia, and the blistering passages in Anna Clyne’s On Track with surgical precision. Though the technical fireworks are impressive, Stepanova’s articulation truly stands out. The precise articulation and touch heard in the swelling quasi bisbigliando gesture that opens the third movement of Badie Khaleghian’s Táhirih The Pure (both a premiere recording and a commission) is both crisp and fluid, and but one example of the intense attention to musical detail Stepanova brings to each work.

The album closes with Piglia by Pablo Ortiz and Gabriela Lena Frank’s Karnavalito No. 1. Ortiz’s work is written as an homage to the author Ricardo Piglia, and after a wandering introduction it settles into what the composer describes as a “relentless milonga pattern showing the kind of intense passion normally associated with the tango.” For me, the ending was spot on – a slight fading away leading to an upward gesture reminiscent of an incomplete question – and Gabriela Lena Frank’s work serves as a fitting answer and closing work for the album. According to the composer the piece “is inspired by the Andean concept of mestizaje . . . whereby cultures can co-exist without one subjugating another.” The piece provides Stepanova a chance to once again dazzle the listener with virtuosic precision, and the slightly puckish ending provides a sound thematic and musical conclusion to the album.

This album warrants attention on its musicality alone. But, I am also drawn to it for its quiet insistence that music (as is true with most things) is best as a shared experience that makes a space for all. I’ll be seeking out more music by the composers featured on this release, and I look forward to the new music that partnerships with engaging performers like Liza Stepanova will continue to produce.

Leave Comments Below!

New Release from Iceland

Gyða Valtýsdóttir (Epicycle II), release date August 28th on DiaMond/Sono Luminus

Gyða Valtýsdóttir first appeared on the scene as a member of the group múm, an experimental electronic Icelandic group, whose second album, Finally We Are No One (2002) reached as high as Number 16 on the UK Independent Album chart. She then left the band to go to conservatory to pursue her studies as a cellist; earning a Master’s degree from Musik Akademie, Basel, in the increasingly popular dual degree of area of classical performance and free-improvisation. After a period of years touring and collaborating with the classical and electronic stars of Iceland’s musical sky, and obviously informed by her studies in Basel, she released Epicycle (2017), a compilation of interpretations of some of the greatest works in in the Western Canon. From Harry Partch’s Ancient Mode to Robert Schumann’s “Im Wunderschönen Monat Mai” the selections are pieces that are well known to most Music History teachers as strong pedagogical tools, the strength of Valtýsdóttir’s work is that she revives this music in a modern context.

This summer, on August 28th, she is set to release a sequel, Epicycle II which is composed of works by Iceland’s top notch contemporary composers. As she describes it: “This time I wanted to collaborate with contemporary composers and musicians who have each created their own, unique musical language that doesn’t fall easily into any existing category.” In the tradition of Russia’s “Mighty Handful” or France’s “Les Six” the result is a kind of “Icelandic Eight” or perhaps better “þeir átta,” a coherent documentation of the Icelandic school of composition in the second decade of the 21st Century–and it sparkles with moments of genius. From atmospheric micro-polyphony to heart-rending moments of electronic intimacy, the music is interesting and powerfully drawn.

The CD begins with Unfold by Skúli Sverrisson, an composer and bass guitarist who has won five Icelandic Music Awards, including Album of the year. The track, as predicted, unfolds in a paced mesmerizing development of a single theme with parallel lines in distant registers, implying an underlying (or overlying) polyphony that is just this side of perceptible. Perhaps it is this sonic reflection of the primary melody that Valtýsdóttir is referring to when she describes playing the track as “like dancing in the prism of its light.” The effect is discomforting in a hypnotic way, Mahlerian only in the way it creates a world apart.

Safe to Love was composed by Ólöf Arnalds and bridges the song and lieder tradition with an accompaniment drawn from ValtýsdóttiIcr’s pizzicato cello and serving as counterpoint to her airy, whispering, yet echoed voice. The intimacy in Jónsi’s mixing creates echos to seem to scatter into time and space. Anna Thorvaldsdóttir’s Mikros, is a rushing counterpoint on cello, is brief and disturbing in it’s extended techniques. It seems to channel George Crumb, think “La luna está muerta” or “Vox Balaenae.” Úlfur Hansson’s Morphogenesis evokes a similar “otherworldness” bringing precomposed string arrangements into concert with a custom built analog synthesizer and Valtýsdóttir’s improvisation.

Liquidity is the result of a collaboration with Kjartan Sveinsson at the Berlin Festival for the People in 2019. It is probably the most likely to succeed on the pop charts, sounding as if it were ripped from an epic historical fiction soundtrack, lending itself to some derived form of primal primitivism, yet there is interest in the way it coalesces around a repeated theme in the piano that is both memorable and purposefully incomplete in its many variations. Air to Breath was released by Daníel Bjarnason a decade ago, but it seems tailored perfectly for Valtýsdóttir’s nuanced, supple and warm cello. On an album of mostly premieres, one can understand why Valtýsdóttir included this track as the exception. Jónsi’s Evol Lamina might just be the most interesting track on the collection, a creation from sampled improvisations that borders on Musique concrète, but the samples are brought alive, even humanized by their delicacy in the upper registers as an unrecognizable, sampled bass pursues. The end is abrupt, like a book set down, halfway through the denouement. The last piece, Octo by María Huld Markan Sigfúsdóttir, is another essay on a brief motive, set into counterpoint with Valtýsdóttir extended harmonics. The dizzying variations of the theme suggest an inwardness that is at least uncanny and at most, transcendent.

Iceland arrived on the classical music scene quite late, with the first real concerts only occurring in the early 20th Century. Their first real virtuoso, Ashkenazy, was a Soviet defector. However, they have been actively working to catch up. I wouldn’t be so silly and foundational as to propose an “Icelandic style” that unites them in an intrinsic nationalistic character, but I will propose that it is a burgeoning school around which principles of developing variation, extended techniques and experimental timbres are united into a subtle polyphony of conscious and subconscious aesthetics. Of course the sound is also postmodern, a collage that can be romanticized, as it is in Safe to Love or endowed with expressionistic modernism as in Evol Lamina. In either case, it is interesting, will likely be influential as the various members of þeir átta develop, but most of all worth your time and attention.

Please leave comments below!

Comment Below!

Comment Below!