A Music City Happening

The Healing in ‘Steal Away’

There’s something to be said about artists that know what the people need. Composer Dave Ragland and choreographer Shabaz Ujima, along with over 30 Nashville-area performers, introduced a new work this December that is timely for the moment we’re living. Speaking to the beauty and struggles of Black Americans, Steal Away is ultimately a dance-music-opera hybrid meant for a community in recovery. African American spirituals are a dominant influence, which paints the music with color and aesthetics that would otherwise not exist with standard compositional techniques. So as the art unravels into something profound and thought-provoking, the audience is exposed to the creative child that the two artists have concocted. And my, is it something to experience.

When Steal Away begins we hear a dark and moody overture, followed immediately into a powerful recitative, both of which give a subtle nod towards what’s to come. The religious elements and operatic grandeur is evident throughout, so it’s refreshing to hear such a modern take on classic hymns and forms of singing. With movements featuring traditional hymns such as Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen and This is the Healing Water, the listener becomes drawn into something so purposeful. The program’s transitions into the inner parts of its story are also important to note, as it lends itself to a push-and-pull with the listener that plays with the conventional boundaries of opera. On the surface, one may think the composition is trying to convert the listener to Christianity. Alas, what Dave and Shabaz present instead is a composition that is grand in scope and timely in its message. From the men in skirts, the intentional multi-generational representation, or the rewording of traditional hymns, the two artists convey a story of struggle, hope, and renewal through a momentous lens.

The work overall sounded difficult. Despite this, the musicians in the Diaspora Orchestra played with ease. There were moments of tension that the flute and cello handled with expertise and precision. Jazz-influenced licks that the pianist turned with excellent simplicity. The chamber-style ensemble never once drew the attention away from the performance at hand, rather complementing the dancing throughout.

Conveying the universal feeling of pain, optimism, and renewal, the movements end with a last movement named after the title, as the work’s theme seemingly comes full circle. “Steal away, steal away,”.. the piece does provide more room for wondering and reflection instead of for direct answers. Despite being composed before the COVID-19 pandemic, the message is just as relevant now as before March 2020. Steal Away is ultimately for Nashville and highlights excellent local groups such as Inversion Vocal Ensemble, shackled feet DANCE!, Friends Life Community, and Rejoice School of Ballet. The work purposefully highlights artists typically underrepresented in opera and dance maybe to say, “look at what you’ve been missing out on.”

Art transcends language, life experiences, and political boundaries. Our jobs as artists should be to create things that reflect the times we live in, and the duo of Dave and Shabaz delivered a moment of tranquil yearning. Not yearning for the time we come from, but instead for a future that is not quite here yet. So despite Steal Away‘s message being something that might take time to interpret, we can still be prepared to value art at all ages and stages of life and fight for what is right.

Veterans Day Concert

Fantastic Musical Moments from the Nashville Reading Orchestra

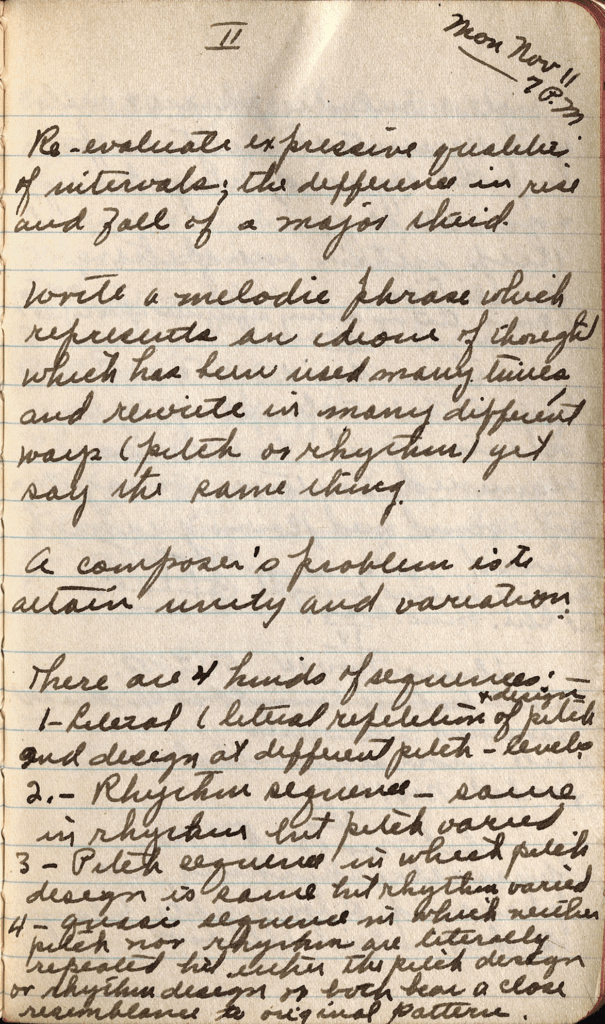

The Nashville Reading Orchestra, one the city’s newest performing arts organizations, gave a Veteran’s Day concert this past Sunday night and it was my first opportunity to hear the ensemble live. Founded by Dr. Joshua Shepherd in the summer of 2020, the orchestra was created to give members of the Nashville community a place to come together to read through a wide variety of orchestral music and present concerts together.

This Veteran’s Day concert was held at the ensemble’s usual home, Nashville First Baptist Church. Inside, the church is quite lovely with a towering stained-glass window seated right behind the altar. Matching the beauty of the church was a quite good acoustic. The layout of the stage caused for some interesting seating arrangements, with the trumpets located behind the percussion and the open lid of the piano. Even with the seating quirks not much was lost aurally.

This concert had a mix of minor annoyances and fantastic musical moments. One vexation came from the program booklet. Upon entering the church, I was greeted and shown a table with four sheets of paper each containing a QR code. Two codes led me to donate through Venmo and PayPal, one led me to an audience participant survey, and the last led me to the program. Scanning the program QR code opened the Google Docs app where I was denied permission to access the document. I requested access to view the program, but access was not granted until two hours after the concert ended. I am a big fan of digital programs replacing physical ones, although it seems as if a simple test beforehand could have solved this problem.

Promptly at six o’clock Dr. Shepherd, sporting a black suit and American flag tie, mounted the podium and led a spirited play through of the National Anthem. Everyone rose and followed along with the music reverently. The feeling of national pride and honor to the Veteran’s was one of my favorite experiences of the concert. This feeling was brought up again when the orchestra played the Armed Forces Salute by Robert Lowden towards the end of the concert. This piece is a compilation of the various US Military branches’ songs. Prior to the piece Dr. Shepherd encouraged any Veterans in the audience to stand when it was their branch’s song was played. One flute player in the orchestra and one audience member stood throughout the piece. The audience was eager to show their appreciation for the two service members. This again, was an effective moment because the audience was engaged with more than just the music itself.

The programming throughout the concert was just fantastic:

Star Spangled Banner – John Stafford Smith

Fanfare for the Common Man – Aaron Copland

American Salute – Morton Gould

Forrest Gump Suite – Alan Silvestri, arr. Calvin Custer

Variations on a Shake Melody – Aaron Copland

Hymn to the Fallen – John Williams

American Frontier – Calvin Custer

Armed Forces Salute – Robert Lowden

Battle Hymn of the Republic – William Steffe

Stars and Stripes Forever – John Phillip Sousa

These pieces easily fit within the concert’s theme and yet were able to span a wide variety of genres: film music, patriotic medleys, marches, and more. No piece dominated the concert and the number of pieces allowed for quite a bit of variety throughout the concert.

Throughout the one-hour concert the orchestra played splendidly. In Fanfare for the Common Man the brass commanded the audience’s attention and did not fail to lose it for the rest of the concert. The woodwinds, and piccolos in particular, shined in Sousa’s Stars and Stripes Forever as they nailed the tricky leaping melodies. The strings seemed their best in the film music from Forrest Gump and John Williams’ Hymn to the Fallen. Some of the harder passages from Appalachian Spring were a little rough around the edges, but for a community orchestra they embraced the challenge and gave an effective performance of the piece.

In the wake of the pandemic and online streaming concerts I have begun to think that the concert going public deserve a complete package of an experience that is more than just the music. Part of this package is accessing the program and another part is engaging with the musicians and other audience members. A further plus for this Veteran’s Day concert was that during the Battle Hymn of the Republic the audience was able to stand and sing along during the last chorus of the piece. Moments like this create an experience for the audience member that is valuable. I look forward to the next time that Dr. Shepherd and the Nashville Reading Orchestra put on a concert.

To find out more and support the work that the Nashville Reading Orchestra is doing you can find them on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/nashvillereadingorchestra/

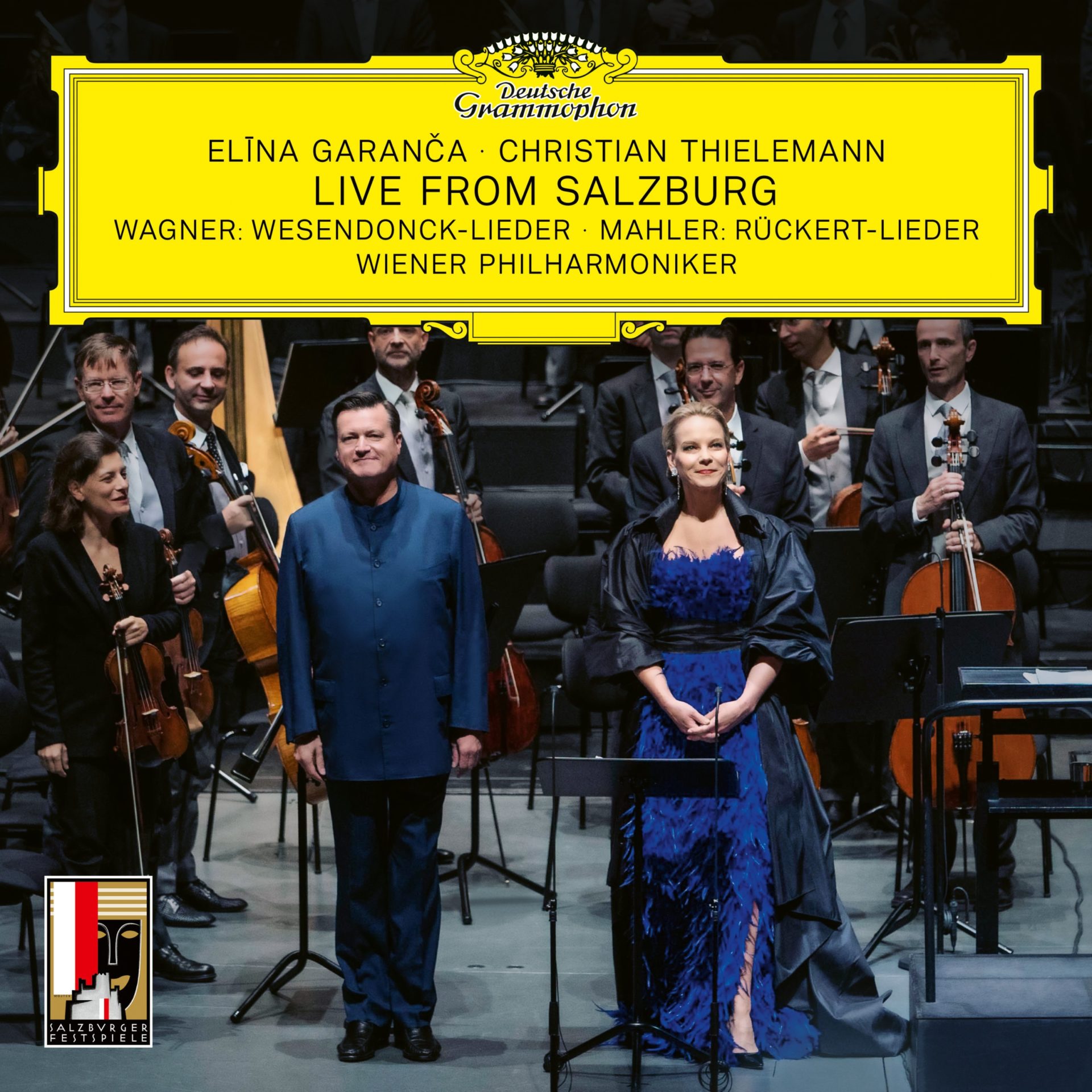

New from Deutsche Grammophon

Live Concerts and Musical Transcendence in Deutsche Grammophon’s ‘Live from Salzburg’

In Deutsche Grammophon’s upcoming release Live from Salzburg, which features astounding recordings of Richard Wagner’s Wesendonck Lieder and Gustav Mahler’s Rückert Lieder, the power and range of Elīna Garanča’s voice are on full display. Her lower notes resonate with decisive power, while her dynamic control in the upper register allows her to follow the emotional trajectory of these works, sometimes mournful and weeping, sometimes enraptured, with skill and grace. This recording comes from two live performances at the Großes Festspielhaus in Salzburg, one in August of 2020 and the second in August of 2021. The title of this release centers the fact that it was recorded in a setting many of us once took for granted—seated in an auditorium full of other music lovers and the musicians themselves, allowing the vibrations from the instruments to reverberate through us directly—and yet, one whose specialness is now all too clear. Here is a recording of a concert celebrating the importance of live music that we can all enjoy from the comfort of our homes—a moment of time, originally rendered special by its impermanence, captured permanently as so many virtual bits of data. What we have then is a wonderful recording that leaves us with a few important unanswered questions about what classical music means in the 21st century.

Wagner’s Wesendonck Lieder, written between 1857 and 1858, are settings of poems written by Mathilde Wesendonck, who was married to one of Wagner’s financial supporters, and with whom he apparently had an extra-marital affair. The secretive nature of their relationship, and the emotional turmoil that resulted, appears to be the subject of these poems and the inspiration for Wagner’s passionate setting of them. Mahler, on the other hand, did not have any sort of personal relationship with Friedrich Rückert. These songs were written not only separately from one another, but also do not even comprise the entirety of Mahler’s Rückert settings. Mahler also set five more of Rückert’s texts in the 1904 songcycle Kindertotenlieder.

What these works have in common, however, is that neither was originally conceived as a song cycle with a fixed movement order nor were they originally written for a full orchestra. Over time, however, through performances of these songs in arrangement, they’ve come to exist as complete works after the fact, as proper song cycles. And yet, song cycles are not mere collections of songs; rather, we should understand that in grouping or juxtaposing these songs, some new meaning, something not present or emphasized in any of them individually, should come to light. In other words, it isn’t just that all of the songs have something in common and are thus grouped together, but instead, even songs that seem unrelated, by being placed in the context of one another, give rise to something completely new. This means with works like Wagner’s and Mahler’s here, where there is no fixed order to the movements, the meaning of these works, their narrative ebb and flow, is created in real time at the whim of the programmer.

The task is fairly straightforward with Wagner’s settings of Wesendonck’s poems. The circumstances in which Wagner set these poems and his relationship to their author create a clear enough scaffolding from which to build the rest of the song cycle. Indeed, I think the narrative of the Wesendonck Lieder is one we can only really understand after the fact, anyways. In large part due to its relationship with the opera Tristan und Isolde (1865), which Wagner was composing at the same time as the Wesendonck Lieder. So powerful was the opera’s force of gravity, Wagner himself labeled two of the settings (“Im Treibhaus” and “Träume”) as “studies” for the work. They are studies not only in composition, although it’s clear to see Wagner’s early experiments with the elliptical, suspension-laden harmonic language of Tristan and a number of its actual musical themes, but more importantly, one can also see the beginnings of its philosophical ideas. In the years preceding Wagner’s work on both Tristan and his settings of Wesendonck’s poetry, he had undergone a fairly important philosophical realignment, spurred on primarily by his contact with the works of philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer.

Schopenhauer’s work, inspired in part by Plato, Spinoza, Kant, and the philosophy of the late Vedas, describes a world comprised of cyclical, endless will or insatiable desires, what he called the Noumenon. The world as we know it, what Schopenhauer called the Phenomenon, is but a representation of that will, an “objectification” of it. The suffering that conscious beings experience results from an inability to escape the world of the Noumenon and of endless will, as well as the falseness of its representation in the Phenomenon. What Wagner found most compelling was Schopenhauer’s assertion that art has the ability to temporarily interrupt this suffering, by offering a brief moment of transcendence—art for art’s sake. Clearly these ideas had a fair amount of influence on the thinking of Mathilde Wesendonck as well, whose poems outline these same problems, even if the conclusions she arrives (or appears to arrive) at differ from both Schopenhauer’s and those that Wagner put forth in Tristan.

Take for example the poem “Stehe still!” (Be Still!), which is often performed as the second song in the cycle, which begs the “rushing, roaring wheel of time” to come to a stop long enough that the poem’s narrator might “in sweet forgetfulness…take the full measure of all [their] joy.” Wagner depicts this ancient, unstoppable wheel of time in a quick 6/8 with a fast-moving sixteenth-note figure and a stammering, almost-frantic vocal line. This gives way in the second half of the song to a gentler homophonic texture, and by the end, to a bright, tonally unambiguous cadence in C Major. It seems evident that Wesendonck’s wheel of time is a more poetic rendering of Schopenhauer’s Noumenon. She at one point refers to it as “urewige Schöpfung” (or “eternal creation,” although the “ur-“ prefix suggests something that’s somehow even more ancient than eternity), and begs for an end to its “Werden” to the act, or maybe more accurately the eternal state, of becoming. These same ideas resurface in the Act II love duet of Tristan und Isolde, where our lovers plead with the forces of night and day to come to a halt, that they might remain in each other’s arms for eternity. Although here, Wagner has taken Schopenhauer’s ideas a step further. Instead of moving from a busy, unsettled musical world to one of blissful harmony, in Act II of Tristan, Wagner conveys timelessness through heavy syncopation that completely obscures the underlying meter and leans in on harmonic ambiguity and dreamy elliptical cadences to depict the cyclical nature of will and desire.

In the next song “Im Treibhaus” (“In the Greenhouse”), she meditates on how this eternal becoming creates such a potent, yet vague feeling of dread. The poem’s narrator stares at the plants in a greenhouse, all of which seem to be silently screaming out in pain, and she intuits that they’ve somehow come to understand the true nature of things—that all things face the same bitter ending. By the end, they even seem to be crying. Wagner later reworked the same mournful music from this song into the third Act of Tristan, at the moment in which Tristan too faces the specter of death but has yet to reach enlightenment.

That enlightenment comes in Wesendonck’s poems in the fourth song, “Schmerzen” (Pain), where she asks why the sun must set every day. She finds consolation, ultimately, in the fact that the sun must set in order to rise once again. If death begets life, and pain joy, she concludes, then the suffering nature has imparted to her must also be a gift. Notably, Wagner and Wesendonck have swapped the significance of day and night. For Wesendonck, day represents happiness, warmth, and life—night the absence of all three. Wagner, on the other hand, treats day and night as clear analogues for Schopenhauer’s Phenomenon and Noumenon respectively. Tristan and Isolde dread the return of the day and the realities of the world and plead for endless night.

The last song “Träume” (Dreams) ends the song cycle in a sort of revery, where the narrator of these poems seems to have found a final sort of comfort in the transcendent world of dreams, much like Isolde realizes by the end of the opera that she and Tristan can only live together forever once they’ve transcended the false world of the living. Perhaps we can read this final retreat into the world of dreams as Wesendonck’s own poetic version of Schopenhauer’s aesthetic experience, the one possible respite from perpetual will.

And yet, it is ultimately the order these songs are performed in that allows us to read Wesendonck’s poems and Wagner’s later extrapolation of them in Tristan und Isolde this way. This is probably why the order of the songs in Wagner’s song cycle tend to be fixed, whereas few recordings of Mahler’s Rückert Lieder present the songs in the same order, and many of them even omit one or two altogether. Even Dorothea Walchshäusl, who wrote the liner notes for this recording, seems at a loss to find a way to draw these songs together under a single theme. She alludes to the text as a common thread (presumably meaning that they all stem from the same poet), but that the “individual mood that Mahler conjures up for each song” is “a far more striking characteristic.” But if we give the Mahler songs the same treatment as the Wagner, and look to the ordering of the songs for a hint, the final three, “Um Mitternacht” (At Midnight), “Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder” (Don’t Look at My Songs!), and “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen” (I Have Lost Touch with the World), seem to center the importance of music as some form of respite from the horrors of the world, which at once is a nice subtle connection to the Wagner songs, but also seems inextricably linked to the circumstances that serve as the primary frame for Walchshäusl’s liner notes—the COVID-19 pandemic. Mahler’s songs are expressive and unique, and the color of his orchestral writing is on full display in these songs. Elīna Garanča and Christian Thielemann’s interpretation of the Mahler songs is exceptional, and the quality of this performance ultimately overshadows whatever nebulousness might arise from programming these songs, never necessarily intended to be understood as a single work, together.

For as much as Live from Salzburg leans in on its live-ness in its title, liner notes, and even its marketing copy, there is a conspicuous absence of applause at the end of each work. Beyond the occasional cough during the Mahler, there are very few auditory clues of the album being live. Perhaps this is intentional, an attempt to bookend each work in complete silence, to allow the works to exist beyond the mundane, even false world of Schopenhauer’s Phenomenon. And yet, I can’t help but think that in the end the appeals of concertgoing in the first place are all its living qualities, the fact that it can’t be pulled apart from its surroundings. Wagner and Schopenhauer could not have imagined high fidelity recordings or WAV files, but perhaps if they could have, it might have invited a moment of doubt in their conclusion that the world of aesthetics provided a way out of the endless suffering of Noumenon and Phenomenon. How can it be simultaneously true that what we want out of art is transcendence from the real world, and yet that after nearly two years of only being able to listen to music digitally, what so many of us seem to want is to be back in the midst of that real world? No doubt this is an exceptional recording of a marvelous set of concerts, and yet there remains a certain contradiction between its reverence for live, embodied performance and the insistence in its presentation on the kind of sonic flawlessness that only audio engineering can bring. Maybe this speaks ultimately to many of the broader problems of contemporary classical programming. Despite how much we love these works, and maybe to some extent because of our reverence for them, they aren’t timeless, and their ability to speak to the present is limited at best and fraught with contradictions at worst.

In preparing this review, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking through how best to frame the performance of the Mahler songs. Not just to speak to the circumstances under which they were composed, but how their performance now might change how we understand the songs themselves as well as our own time. The Wagner was fairly easy, although admittedly requires a fair amount of exposition to be able to articulate. But my (and Dorothea Walchshäusl’s) difficulty in trying to give Mahler this same treatment illuminates this fundamental problem, I think. Just as there is a barely noticeable rift between Deutsche Grammophon’s stated reverence for live music and the engineering decisions in the final product, anyone who sets out to write about classical music in the 21st century, regardless of the topic or audience, must first contend with, almost without noticing it most of the time, how in the world music which is ostensibly “universal” and “timeless” could possibly also be relevant to people in the here and now. “Which is it?” I guess, is the question I’m left with. Is music meaningful to us because it transcends the earthly realm, or do we enjoy it precisely because it’s made by other human beings in a particular place and time and only truly exists in the fleeting moments that its being performed? Is classical music worth listening to and writing about because it in particular rises above the confines and intentional obsolescence of fleeting musical styles, or is its grounded-ness in particular sociopolitical and economic contexts what makes it possible to even contextualize the here and now through its lens in the first place? I really don’t know, but I suspect that the truth is that these paradigms are too limited in the first place, and if we are ever to finally answer that perennial question of what role classical music should play in the contemporary world, we must first find a way past the contradictory roles we expect it to play in our lives.

At Oz Arts Nashville

Puremovement in OZ

Oz Arts Nashville kicked off their 2021-2022 season with a residency in October from Rennie Harris’s Puremovement ensemble, an energized blend of street dance and hip hop choreography morphed into staging and narrative structures. A lively atmosphere pervaded the venue before showtime, purple and blue lights warming up the gently rising stands as classic early 2000s hip hop played at a comfortable level (Lights, Camera, Action; Roc the Mic; and of course C.R.E.A.M. all making a sonic appearance). The audience of all ages reacted with a rowdy noise of approval as Executive & Artistic Director Mark Murphy took to the stage to announce the full season of in-person programming and residencies.

With introductions out of the way and mood set, the following hour flew by. The 6 core dancers of the Puremovement group, gathered from around the globe, alternated in the spotlight. Beginning the show center stage in a ring with a bit of demonstrative introduction of each member’s physical style, they cycled on and off stage executing Harris’s unique vision. While at times unison movement in group numbers was precisely executed, other moments would allow for individual expression, from flashier footwork and aerobic breakdance maneuvers to more contemporary dance fluidity. Even a splash of what appeared to be voguing popped up a couple times, which fit with the house music in a couple of the selections. As the pieces progressed, later movements of the “Nuttin’ But a Word” suite mapped out pairs and trios of dancers utilizing the full expanse of the stage in spotlit pools of light. In between several of the movements, video clips of Rennie himself played, briefly elaborating on the desire to progress street dance and avoid stagnation. For those more informed viewers & readers, the suite incorporated specifically elements of Campbell locking, house, hip-hop and B-boying. [Aside from attending a couple b-boying Battle@Buffalo competitions as a spectator up in new York state years ago, I was hardly a keenly discerning eye, the finer delineations between styles escaping me but still an obviously varied language of rhythm & movement on display].

Joining the Puremovement dancers at the outset of the show and then making a longer appearance in the last few pieces, another group of 4 dancers, The Hoodlockers, weaved into the staging, adding their distinct flavor of pulsing locking movements from New Jersey to the melting pot of dance on display.

Musical selections also were varied considerably, from early hip hop grooves to more electronic-influenced beats, and even veering into jazzy mixed-meter with a piece choreographed over Al Jarreau’s “Blue Rondo A La Turk”. As some of the more subdued musical selections by Cinematic Orchestra created a temporarily less energized atmosphere, some key lighting changes within pieces helped to set the stage in a wash of reds or stark blues & whites.

With some of the pieces on the program flowing into each other with hardly a pause, it was easy to get lost in the pacing. Indeed, the ending came as a surprise, thinking there were still a piece or two left after attempting to follow along and jot notes next to titles in the flyer, but a glance at the watch showed an hour and fifteen minutes had passed in a snap. As the audience filtered out into the lobby and parking lots of a still-warm early fall night, a buzz of happy chatter rehashed the night’s performance, a cohesive and visually stunning way to begin afresh a new season of arts & entertainment in Nashville.

Nashville Opera

Opera on Wheels Comes to the Parthenon

On Sunday, October 17th, Nashville Opera presented “Opera in the Park” as part of its Nashville Opera on Wheels series. It was a recital of chestnuts from local artists performed on the sunny lawn aside the Parthenon. Highlights included Emily Apuzzo Hopkins and Clemintina Moreira’s silky “Barcarolle” from Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffmann, Tamica Nicole’s nostalgic rendition of Puccini’s famous “O mio babbino caro” and the “Toreador Song” performed happily by the entire ensemble with Jeffrey Williams as the bullfighter from Bizet’s Carmen. All numbers were accompanied eloquently by the wonderful Amy Tate Williams. A very nice afternoon activity, it makes one impatient for the wonderful upcoming season from Nashville opera, which begins in January with a premier of Marcus Hummon’s Favorite Son!

The Nashville Symphony

Fanfare for Music City

They are back.

The Nashville Symphony has returned home to the Schermerhorn Symphony center. Some things have changed: masks are ubiquitous, physical programs are replaced by digital counterparts, and the fantastic preconcert lectures from Music Director Giancarlo Guerrero are now presented on YouTube. Back in March 2020, to the shock of many, the Nashville Symphony Orchestra was the first U.S. orchestra to completely shut down the rest of their season. As the pandemic progressed many orchestras quickly followed suit. Eighteen months later they have returned with a cautious season mapped out ahead.

The arc of the 21-22 Nashville Symphony season is growth both musically and instrumentally. Towards the beginning of the season, like this weekend’s concerts, the orchestra presents small chamber groups and pieces that generally require less performers. Heading into 2022 the orchestra expands to a regular size and eventually will present Stravinsky’s Firebird with the Nashville Ballet. The season wraps up in June with Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, which is coincidentally the last piece I saw Maestro Guerrero conduct live in 2019 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Tanglewood.

Walking towards the Schermerhorn last night, I was truly excited. It had been a long time since I had heard a live symphony orchestra. The program that night, billed as a “Fanfare for Music City,” served as a great potpourri of the different instrumental sections of the orchestra:

Aaron Copland – Fanfare for the Common Man

Joan Tower – Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman No. 1

Antonin Dvorák – Serenade in D Minor for Winds

Jessie Montgomery – Strum

Franz Schubert – Symphony in B Minor, “Unfinished”

My thoughts about the concert were interrupted walking on Broadway by the noise of honky-tonks and a man on a Segway with a large snake wrapped around his neck (only in Nashville!). Just outside the doors of the Schermerhorn I flashed my vaccination card and received a paper wrist bracelet that allowed me inside. Inside the Laura Turner Concert Hall, I was surprised to find it mostly empty. My brother and I were the only people in our row or the row in front of us. As the concert started CEO Alan Valentine walked to the stage and welcomed everyone back to the Schermerhorn. He thanked donors, corporate sponsors, ticket buyers, and the musicians for making this season a possibility. As Vanlentine left the stage the brass tuned to begin the Copland.

Maestro Guerrero walked onto the stage and with very little hesitation and gave the massive downbeat that begins the Fanfare for the Common Man. Upon hearing the percussive resonance throughout Laura Turner Concert Hall, I was reminded of just how many fantastic concerts I had heard in that room. Restarting the season with a quite literal bang seemed like the right way to begin. The brass and percussion throughout the Copland and Tower really sparkled. Maestro Guerrero’s conducting was strong and showcased the pomp that comes with both pieces. The history behind Copland’s fanfare seemed to overshadow the lesser-known Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman. This may just be an unfortunate side-effect of linking the pieces so closely together. The Fanfare for the Common Woman is an exceptionally fine piece in its’ own right and the Nashville Symphony has done a tremendous amount to champion Joan Tower’s music with multiple recordings that have been nominated for a Grammy and even won one.

These two pieces totaled barely six minutes and then Guerrero turned to address the audience. Showing a bit of emotion, he welcomed the audience back home and thanked them for the support they showed during the course of this pandemic. It was a moving moment for all, and the audience replied with some of the largest cheers of the whole evening. As Guerrero gave a bit of backstory behind the two fanfares the ensemble for the Dvorák Wind Serenade entered the stage. The Wind Serenade in D Minor is a miniature quasi symphony. The piece is in four movements with a march, minuet, andante, and a rousing polka. Interestingly, it is scored for double oboes, clarinets, bassoons, and three horns. In a later revision Dvorák added a cello, double bass, and contrabassoon.

Whereas the opening Fanfares featured the brass sections as a united whole, the Wind Serenade did much to highlight individual instruments. Particular kudos goes to principal oboe Titus Underwood whose flexibility and versatility was highlighted constantly in the score. What particularly stuck out to me during the Dvorák was the amazing blend of the ensemble. Dvorák’s great orchestration helps of course, but an inattentive ensemble can steamroll that. This was not the case here. As melodies and themes moved around the ensemble the group was able to respond and allow their colleagues to sing through. This is true chamber music, a rare treat to hear it in the Schermerhorn. Maestro Guerrero was at ease leading this intimate music, though still kept the intensity throughout.

Maestro Guerrero was at ease leading this intimate music

Before Jessie Montgomery’s Strum Guerrero turned and addressed the audience further about his fondness for the piece. It was great to hear the Music Director speak while the stage was being rearranged for the new piece. I always enjoy the concert more if the Music Director addresses the audience verbally. This allows them to share their

passion and excitement with the audience instead of just walking to the podium and turning their back to the audience to conduct. Strum was an unknown piece to me, and I was looking forward to hearing the work live. Jessie Montgomery’s work has been increasingly showcased throughout performing arts ensembles recently, and for good reason. Her music is fresh and exciting. It is fun to hear and the players have fun playing it. And frankly, it was nice to have something written this century on the program. With the strings spaced out across the expanded stage some timing issues presented themselves but overall, this piece was the highlight of the concert for me. Beginning with a strumming viola this piece has everything one could want from soaring violin melodies to furious energy throughout. At seven minutes long it is the perfect length, Jessie did not stretch the musical material further than it could go. In the preconcert lecture Giancarlo mentioned that this piece has become a personal favorite of his and he plans to take it around the world with him as he guest conducts this year.

Last on the program was Franz Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony No. 8. Being the ‘warhorse’ on the program my expectations were high. The program had been building the orchestra slowly section by section and now was the moment to hear the full ensemble. There were a few balancing issues as they shook off the rust of 18 months apart, but very quickly the ensemble settled together, and the Nashville Symphony was back in all of its glory. This is truly one of the gems of the orchestral repertoire and the ensemble executed it to near-perfection. Sudden loud outbursts were electrifying. Nervous tremolos in the violins heightened the tension. Schubert’s melodic gift was on full display. In introducing the piece Giancarlo mentioned that he programed this piece solely because of the title “Unfinished.” He spoke about how in the past two years we have had many projects, events, and concerts that were left unfinished. With the conclusion of this opening concert, I doubt this season will be left unfinished.

Overall, this was a strong opening weekend for the group. In the future I hope that the Nashville Symphony continues to refine their online presence. (Even with the re-introduction of live concerts, online content will not disappear.) The quality of playing is world class and if you have been missing live orchestral music then I invite you to check out their remaining performances this weekend. If you would like to welcome the Nashville Symphony back home, then you have two more chances on Friday the 17th and Saturday the 18th. You can find tickets here. Before attending please be aware of the Nashville Symphony’s new Health and Safety Plan that you can find here.

From Oz Arts

(Coming in October) Rennie Harris and Puremovement in ‘Nuttin’ But a Word’

OZ Arts Nashville Presents Award-Winning Choreographer Rennie Harris and His Company Puremovement in Nuttin’ But a Word

The life-giving mix of street dance, hip-hop and contemporary dance takes the stage October 14-16 with public lecture-demonstration presented in partnership with the National Museum of African American Music on October 13, 2021

Nashville, Tenn. – September 10, 2021 – Contemporary arts center OZ Arts Nashville opens its ninth season of contemporary performances with high velocity Hip-hop and contemporary dance by internationally-acclaimed choreographer Rennie Harris and his Philadelphia-based company Puremovement, October 14-16, 2021 in OZ Arts’ expansive warehouse. The company’s critically praised production Nuttin’ But a Word is a virtuosic and high energy mix of Hip-hop, Street and contemporary dance forms, demonstrating why The New York Times called Harris “the most profound choreographer of his idiom.” As part of the company’s Nashville residency, Rennie Harris Puremovement will host a free, interactive community lecture and performance demonstration on the history of Hip-hop dance at the National Museum of African American Music on October 13, 2021 at 7pm.

Hailed as “the Basquiat of the U.S. contemporary dance scene” by The Times (London), Harris founded Puremovement in 1992 as a street dance theatre company dedicated to preserving and disseminating street dance culture through workshops, classes, lectures, mentoring programs, and public performances. The group’s mission is to provide audiences with a sincere view of the essence and spirit of Hip-hop rather than the commercially exploited stereotypes portrayed by the media. In his prolific career, Harris has also been honored with numerous prestigious awards, including the Alvin Ailey Black Choreographers Award, the Guggenheim Fellowship, the Doris Duke Arts Award, and the Dance Magazine Legend Award.

Nuttin’ But a Word challenges the foundation of Hip-hop and serves as a reminder that without individuality, creativity and innovation, the dance form will not evolve. Harris is celebrated for creating work that is fresh and surprising yet rooted in deep knowledge and a scholarly background in the history and traditions of Hip-hop. This acclaimed new work features his signature mix of highly skilled Street dance with intricate contemporary forms, all underpinned with lively music.

“Renowned choreographer Rennie Harris and his company, Puremovement, will give our community a new perspective on the incredible history of Hip-hop and other contemporary dance forms,” said Mark Murphy, OZ Arts Executive and Artistic Director. “His ability to challenge stereotypes and give a voice to new generations through the ever-evolving interpretations of dance contribute to his phenomenal success as a choreographer and Hip-hop ambassador. Nashville will not soon forget the first time they saw Rennie Harris Puremovement.”

In addition to performances at OZ Arts, Harris will host a free lecture-demonstration at the National Museum of African American Music (NMAAM) as part of their Fine Tuning: A Masterclass Series on October 13, 2021. Titled “The History of Street Dance,” the event includes a 45–60-minute interactive presentation and history of various street dance styles, including beginner Hip-hop, House, and Breaking. Reservations to attend the event in-person are required and can be made on the OZ Arts website. The event will also be live streamed via NMAAM’s Facebook channel at www.facebook.org/theNMAAM.

Tickets for Nuttin’ But a Word start at $25 and are available now at https://www.ozartsnashville.org/rennie-harris-puremovement-nuttin-but-a-word/. OZ Arts is invested in the health of its guests, artists, and the overall community. As such, proof of vaccination or a negative COVID-19 test (taken within 48 prior to the event) is required to attend this event.

This performance is made possible with generous support from donors and grants, including funding from the Special Arts Access Grant from the Tennessee Arts Commission. To learn more about upcoming performances, please visit https://www.ozartsnashville.org/.

A New Season!

The Nashville Symphony at the Ascend: Beethoven under the Stars

It’s been a pandemic, and after a year and a half of tracking quarantines, vaccines and rates of infections, folks are desperately trying to get back to normal. For me, and apparently for the large number of people who attended the symphony last Saturday, one of the markers of the return to normalcy is the Nashville Symphony playing concerts again. Indeed, the Ascend Amphitheater enjoyed a rather full house for the Symphony’s season opener, headlined as “Beethoven under the Stars” and featuring both Beethoven’s 5th Concerto “The Emperor,” (played by Stewart Goodyear) Beethoven’s famous 5th Symphony and Samuel Barber’s plaintive Adagio for Strings. The evening got off to a bumpy start, though I don’t think it was the fault of the Symphony, and ended well enough.

Honestly, the evening’s weather was good, in fact, quite beautiful—mid-seventies and a clear sky. We parked in the lot just on the other side of the pedestrian bridge, as we always do, and walked across for the concert. My wife is 6 months pregnant but certainly up to the task for a little stroll in the night air. The bridge was full of the typical folks, lovers and tourists taking selfies in front of the skyline, buskers playing for tips. This night featured a guitarist playing/singing an old country tune and a few paces beyond a cellist playing the first prelude from J.S. Bach’s 1st Cello Suite; it was a quite pleasant moment. Then as we began to descend the other side of the bridge an itinerate white preacher with a microphone and amplifier was screaming his political ideology at us as we passed, “It’s Adam and Eve! Not Adam and Steve sinner, repent! Repent! REPENT!!!” I don’t know why he was yelling at us, since we are a simple, “run of the mill, cisgender, heterosexual” couple, but you know, it IS the south. We finally got off the bridge and were nearly run over by three passing drunks on scooters. (I’m happy to see that there are folks that are tired of people treating our city like the state’s dive bar.) We arrived at the Ascend theater to pick up our tickets 15 minutes before the show and it only took 25 minutes to get our to our lawn seats in an area peppered with a diversity in distractions.

Settling in just a few moments into the first movement of the concerto, it was troubling to see a closeup of Goodyear’s fingers running on the ivory keys but being unable to hear the piano over the orchestra. It took largely the first half of the movement for the balance to be corrected. Thankfully, by the time he reached the cadenza, the issues had been worked out and the orchestra was sounding quite nice.

Beethoven’s 5th concerto is commonly called “the Emperor” in English speaking countries, it is not a name that Beethoven knew of or certainly approved of. However, the movement does carry some significant heroic qualities that mark Beethoven’s middle period: it is in the heroic key of E-flat Major, the soloist opens and directs all modulatory passages in the movement and the primary theme of the opening movement seems to combine a fanfare with a dotted march figure.

It is this kind of topic-laden music that Maestro Guerrero is excellent at articulating, and the string section brought it to the fore with a striking exuberance. When it came time for the famous cadenza (Beethoven demanded that the pianist play what is written and not improvise themes on the spot) Goodyear brought a sense of excitement and genuine flair to these simple yet virtuosic variations on the movement’s themes—particularly by isolating and emphasizing the lyrical central section of the final cadenza and with light, gentle trills that brought out nostalgia for the classical side of Beethoven here, at the height of his romantic poetry. Needles to say, by the end of the first movement, I was “into it.”

The second movement’s quiet nocturne allowed me to settle in and recognize my surroundings. Look at the distant river, the flashing lights streaming quietly heavenward from Nissan stadium, and the small family in front of us, a woman who was managing to keep her two school-age sons attentive through the entire concert. Goodyear’s dialogue with the orchestra was amazingly eloquent and I was quite lost in the moment when the music from a passing car blaring Shania Twain (“Man, I feel like a woman!”) shook me from my reverie. In the third movement, from the lovely, buttery toned transition on Titus Underwood’s oboe to the grand arching theme thundered by the whole orchestra, it was made clear that the Nashville Symphony was back and ready to play.

After the first piece, Maestro Guerrero took the moment to speak. He mentioned the catastrophe of twenty years ago, which this concert was meant to memorialize, and tied it to the current epidemic. He described Barber’s Adagio as a piece that was played often twenty years ago to lament the catastrophe. He then offered the final piece, the 5th symphony as the most famous musical composition in the world, another of Beethoven’s great, heroic compositions, and dedicated it to the essential workers, from grocery clerks to health care specialists whose work allowed us all to gather tonight. There was a strong response from the crowd and he turned to begin the Adagio.

The problem with the Adagio it that it is a slow, gentle depiction of tremendous suffering. Its slow, ascending stepwise motion moving in tandem with rigid harmonies depict a sad aural circle that seems to have no release. As a plane flew overhead again, my thoughts wandered to the 9/11 attackers and the ensuing war. We have just exited Afghanistan, after two decades and the women of that country are returning to their veil of religious conservatism and dogmatism. Their education will soon be forbidden and the hate for our country will grow again, sowing the terror that started that war in the first place. Sitting in a largely unmasked crowd as infections in Tennessee top the world’s pace, I mourned the delta variant and worried for the slowly emerging “mu” variant. Round and round the suffering goes. The performance was so stirring I was devastated, wondering why they would program such a work in the middle of COVID’s ongoing destruction. Just as the final chords rang gentle in the night air, the voice of a bartender from Ascend’s food row rang across the field “No More Alcohol!!!” providing the escape from reverie that I needed.

Immediately thereafter, the orchestra thundered into the famous fate motive—short, short, short, LONG! This terrifying motive, the seed of the rest of the movement and the basis of motives throughout the symphony, cemented the chill in my spine. As the subject slowly dug his way out of this oppressive C minor into the light of a C major galaxy, I felt a charge of excitement. There will be another vaccine, maybe our diplomacy will work this time. Geez that ambulance was loud and did I see Jun Iwasaki and Erin Hall chuckle at it as they attacked Beethoven’s score with a Joie de vivre? Music City will survive, their biggest band is back, and most importantly, their, no, our next concert will be held safely within the confines of the Schermerhorn! The Nashville Symphony returns next weekend, September 16-18 at the Schermerhorn with the “Fanfare for Music City.” Tickets available here.