Oz Arts Presents:

Ronald K. Brown’s Evidence: Grace, Mercy, and The Equality of Night and Day: First Glimpse

In my past work for Music City Review I have written about only music, whether it is a CD release or a live concert. That sort of work is in my wheelhouse. Then last week I was asked to write about Ronald K. Brown’s dance company Evidence presenting Grace, Mercy, and The Equality of Night and Day: First Glimpse at OZ Arts. When I was asked to do this the phrase “writing about music is like dancing about architecture” came to mind. The originator of this phrase is unknown, but it comes close to my feelings about this review.

In 1985 Ronald K. Brown founded Evidence in Brooklyn, New York with the purpose to integrate “African dance with contemporary choreography, music, and spoken word. Through its work, the company provides a unique view of human struggles, tragedies, and triumphs.” The program at OZ Arts was a shining example of a triptych of works that focused on that mission.

Opening the show was Mercy choreographed in 2019 by Brown. Mercy was originally created as a companion piece to Grace which ended the program. Mercy “focuses on the seeking of compassion, which leads one to have mercy.” Clothed in rich dark costumes, designed by Omotayo Wunmi Olaiya, this piece featured solo dancers struggling with each other until finally ending in a joyous resolve of compassion. This piece was a visual feast with dancers constantly entering and exiting from all sides of the stage. Three pillars of fabric stretched from the floor to ceiling which served as miniature frames for the stage. The upbeat music lent a solid tempo for the dancers to work with. Overall, it was my favorite piece of the evening.

At the very beginning of the evening the audience was told that the next piece on the program, The Equality of Night and Day: First Glimpse, was a work in progress. TEND (as the piece was referred to as) was still in the beginning stages and the final product would be different from what the audience would see that evening. Although this was the case, the work came off as an already fully developed piece. This was the slowest and most somber of the dances that night. The dancers, clad in blue uniforms, circled each other unhurriedly. Taking turns, one dancer would move to the middle of the circle for a solo and take off the top of their costume. The tops were all laid in a pile in the middle of the circle. Aurally, the piece juxtaposed prerecorded speeches by activist Angela Davis with music by pianist and composer Jason Moran. Davis spoke about the dangers of rising conservatism along with the disproportionate rates of incarceration of young black men. The words grounded this piece in the here-and-now unlike the other works that dealt with universal themes. Unfortunately, Davis’ words were an undeveloped critique that distracted from the action on the stage. For me this piece had the highest emotional intensities and the most jarring switches between words and music. I am eager to see what the final product will be.

The final dance was Grace which was created in 1999 and is undoubtably a masterpiece. An angelic figure in white weaved their way through opposing dancers in red. Over time the full company emerged clothed in the warring white and red costumes. This piece was the highest energy of the evening. Throughout the audience began to clap on beat with the music and broke out into applause after a particularly flashy flourish. The energy became infectious and by the end many members of the audience were shouting “Get it girls!” and “Bring it fellas!” to the dancers on stage. The intensity of Brown’s choreography was evident from the sweat flying from the dancers’ bodies. Altogether this was an amazing evening and a great showing for Evidence. Hopefully we have the fortune of seeing them back in Nashville soon.

If you would like to find out more about Evidence please click here. (https://www.evidencedance.com)

Nashville Ballet presents

‘Attitude’ at the Martin Center

Currently running at the Martin Center for Nashville Ballet is Attitude, a series that has developed a reputation for its “game changing choreographies and uniquely Nashville musical collaborations.” This year, presenting two internationally renowned works including Val Caniparoli’s tutto eccetto il lavandino (everything but the kitchen sink), and Twyla Tharp’s Nine Sinatra Songs, alongside a premiere of Fortudine by emerging choreographer Mollie Sansone, the iteration extends this tradition brilliantly.

The evening (I saw the performance on 2/12) opened with the fun and irreverent tutto eccetto il lavandino. San Francisco based dancer and choreographer Val Caniparoli’s “tutto” is a manic masterpiece of confusion and pastiche. The stage is nearly constantly crowded with an ensemble of dancers– men tossing women from arm to arm, and

point to point, littering the floor with pliés, jetés and brisés. This was broken up with a set of three duets, marvelously performed by all, but the highlight of which was the penultimate number performed by Aeron Buchanan and Jaison McClendon. The soundtrack, itself a collage of Vivaldi concerti, was so coldly and objectively baroque that it brought the dancer’s emotional expression into bright and intentional satire—a parody of feeling. In one hilarious moment Caniparoli had the Nashville Ballet’s entire male cohort sobbing openly, uncontrollably, mugging even, to Vivaldi’s tragic sinfonia in B Minor, RV 169, “Al Santo Sepolcro.”

If Caniparoli’s piece lacked narrative, Sonsone’s did not. It’s title might have been taken from “fortitudine vincimus” (through endurance we conquer) which was the family shield of the Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton, or perhaps from the Marine’s motto, or perhaps Sansone’s Latin is simply “on point.” In any case, the story is a moving representation of the emergence of self-expression and the liberation it can model for others, similar in story, but much, much, much more beautiful than that old Macintosh commercial “1984.” Soloist Julia Eisen danced with a riveting power, grace and charisma when confronted by the conformist ensemble. Mycah Kennedy’s workaday-then-suddenly scarlet costuming is marvelous while Larissa Maestro’s gently modernist score, co-commissioned for the ECHO at the Parthenon series by Centennial Park Conservancy, was stirring in the hands of the Lockeland strings.

Finally, the evening ended with the impossibly romantic Nine Sinatra Songs. Accompanied by a collection of “old blue eyes’” greatest hits, and wisely performed by Nashville on the weekends surrounding St. Valentine’s Day, Tharp’s modern, 20th Century work is a charming, silly and amorous collection of duets. Deserving special mention is Michael Burfield for his “rat-pack” machismo in “Softly as I Leave,” and Claudia Monja for her graceful presence in “Strangers in the Night,” for my money, the evening was stolen (again) by both Mollie Sansone and Aeron Buchanan whose dance to “One for My Baby” was one part nostalgia, two parts intimacy, a splash of debauchery and all delight. (see Tharp and Baryshnikov rehearse the piece here). It felt like just another beautiful evening at the Martin Center, like we used to have before…

Attitude will be produced again on the 18th-20th and then Nashville Ballet returns with Lucy Negro Redux on a National Tour, beginning in Nashville on March 18th-26th.

Catalyst Quartet Releases UNCOVERED Vol. 2

Counterpoint: Florence Price and Marketing the Classical Canon

Virtually every piece of public-facing writing on Florence Price in the last five years or so begins at the same place—St. Anne, Illinois, 2009: a long-since-abandoned house that Price had once used as a summer getaway. Behind the walls of this dilapidated house lay a veritable treasure trove of Price’s musical manuscripts and personal papers. Dozens of works otherwise considered lost or that were completely unknown suddenly saw the light of day for the first time perhaps since Price’s death in 1953. In the intervening years, these findings in 2009 have almost completely transformed her legacy. One would be hard-pressed to find a program note or an album booklet from the last five years or so that doesn’t somehow frame Price’s music (even the pieces that had been widely publicly available since Price’s own lifetime) as being in the process of “rediscovery.” This is the case for the upcoming album Uncovered, Vol. 2 by the Catalyst Quartet. The quartet describe the series as “a multi-volume anthology highlighting string quartet works by historically important Black composers, which aims to bring greater awareness and programming of their music.” This second volume is dedicated exclusively to Price’s chamber music for strings, featuring four works for string quartet and two for string quintet, including four world premiere recordings of music from Price’s manuscripts.

Scholars like Kori Hill and Doug Shadle have already pushed back against this framing at length, arguing that claiming Price has been or is being “rediscovered” flatly ignores the fact that much of her music was never lost. It was always available for performance, or in unfortunately rare circumstances continued to be programmed despite a lack of mainstream recognition. Moreover, writers who frame Price in this way, Hill, Shadle and others argue, tend to rely on the passive voice, that is, they tend to write about Price’s years of “obscurity” without ever naming names, without ever acknowledging that it was largely a deliberate act to continue programming music mostly by the same dead white composers when Price’s music (at least a fair amount of it) was perfectly available. In this review I focus on the Catalyst Quartet’s recordings and packaging in light of this conversation, with a specific focus on how marketing, questions of nationalism, and the shadow of the Western Classical Canon continue to limit the ways we talk about Price, her marvelous compositions, and the legacy of classical music.

Before turning attention to these huge questions, I think it’s best to start with Price’s music itself, and the fine recordings presented here by the Catalyst Quartet and pianist Michelle Cann. The works on the album span virtually the entirety of Price’s active life as a composer, from the beginnings of her days in Chicago at the end of the 1920s in the form of two movements for an unfinished String Quartet in G Major all the way to her masterful 5 Folksongs in Counterpoint written in 1951, less than two years before her death. The works in question also highlight Price’s varied strengths as a composer. There are plenty of examples of her incorporation of various non-classical idioms (most notably that of Negro Spirituals, but also plenty of other hymns and popular tunes or styles) into classical forms, of course, but also on full display here is Price’s uncanny ability to couch her elaborate, modernist harmonic and structural schema in an almost-inevitable sounding, neo-Romantic guise. Take for example her settings of “Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” from the 5 Folksongs in Counterpoint, where Price uses the familiarity and relative simplicity of these tunes as an invitation, or maybe a vehicle, to take the listener on increasingly distant harmonic and textural places without ever leaving the original tune behind. Couple the surprisingly subtle complexity of Price’s harmonic plans with an astounding mastery of contrapuntal treatment, and I don’t think it’s hard to see why Price in particular has become such a magnetic figure for re-evaluating concert programming: her music remains approachable and accessible to audiences with limited familiarity with classical music, and yet this accessibility doesn’t come at the cost of depth, or even respect for the audience. Her music is rich and layered, and above all written with that rare combination of well-honed craftsmanship and genuinely irreducible musical creativity that doesn’t require some fancy repertoire of musical terms to enjoy.

So it’s clear, then, to me why we love Florence Price so much and just why her music in particular finds itself in the middle of a programming renaissance. Her music rewards intimate study, but never demands it. On top of that, though, there’s something irresistible about the thought of dozens of masterpieces, written before their genius could possibly be understood, collecting cobwebs in a sleepy Illinois town, waiting for an enlightened future to unearth them. But of course, as Hill and Shadle have carefully pointed out, this is not historical fact, so much as a clever marketing trick. It’s the same kind of marketing trick we like to play with our ideas of Beethoven the tortured genius or with the scandalous premiere of Stravinsky’s Le sacre du printemps. It’s a kind of anti-historical framing that only has anything to say about how we view ourselves today and how we imagine our relationship to the past, but obviously in converting the past into mostly legend, couldn’t even say anything about the past if it wanted to. To be clear, I think this marketing trick is mostly well-intentioned, but it does ultimately come at a cost, and more than just one of historical accuracy for its own sake.

So, then, how exactly do the liner notes for this release frame Price’s life and work, and what are the broader implications of this framing, not only for Price’s music and legacy, but for classical programming more broadly? I think it’s worth being fair to the Catalyst Quartet up front by pointing out that the title of this series of albums seems to push back against the idea that the music of black composers is being “rediscovered.” “Uncovered” suggests to me anyways that something was deliberately hidden and that it is now being brought back to light. The world premiere recordings here aren’t “discoveries” but rather an amplification of sounds that some have tried to silence. I think it serves as a step in the right direction, if not maybe at least still a little self-congratulatory. However, the extent to which this release takes Hill and Shadle’s writings into account (if they actually do at all) mostly stops here.

For one, the liner notes, like many, many other blurbs about Price’s life, reference her compositional style as the fulfilment of some great prophecy by Antonín Dvořák.

Antonin Dvořák, who passed away before ever getting to know Florence Price’s music, championed the idea that a noble school of American composition would come from the folk music of Negro Spirituals. Many white American composers took up Dvořák’s call and the resulting music, perhaps due to its inauthenticity, didn’t carry the gravitas or nobility that Dvořák foresaw. However, the depth and beauty of the works on this disc are a powerful reminder that America’s voice, as prophesied by Dvořák, is found in the voices our history has overlooked and suppressed, the voices of the resilient and steadfast.

I find this framing in general fairly patronizing, but here I find the Dvořák myth even more frustrating than usual. The narrative itself is one that removes agency from Price as an artist, insisting that her stylistic choices had more to do with following a blueprint set out by a dead white composer than as a result of her own artistic skill and intuition. Moreover, the author’s unexplained reference to Price’s “authenticity” in using the music of Negro Spirituals seems to imply some kind of essential connection between black bodies and black music, the kind of racist musical essentialism that Karl Hagstrom Miller documents so thoroughly in his 2010 monograph Segregating Sound. However, I think it’s unfair to frame the Catalyst Quartet’s notes here as purposefully peddling in these sorts of ideas. Rather, they’re likely the accidental result of the sort of imprecise language that works much better than carefully sourced historical prose in the copy of a commercial product.

That said, what remains in any version of the Dvořák myth, regardless of how well written or sourced, is the implicit framing of Florence Price as a figure of American musical nationalism. I think I can understand the impulse to do this, because the idea is essentially that the canon of Great American Composers almost exclusively starts and ends with white dudes, with a handful of white women to speak of, and that by expanding that roster to include non-white composers, it can be made to more accurately reflect the body of American music and of the people who make up the United States in the first place. But I think there is quite a significant difference between being a composer who is American and being an American composer whose music is nationalist in character and content. It’s worth remembering that the national styles Dvořák was interested in cultivating/describing were in service of nation building, i.e. fundamentally and unquestionably a highly specific political project. And while the specifics of American nationalist projects were not the same for Dvořák, for Price, or even for us today, there are certain through lines of exceptionalism and colonial domination that seem not only irrelevant to Price as a person and an artist, but completely antithetical. The impulse to frame Price as a Great American Composer and especially as the heir apparent to the legacy of Dvořák, even if motivated by a desire to elevate her life and work, comes along with a “salvaging” of the same American Empire responsible for the racism and sexism she combatted throughout her life. In other words, the Price renaissance, we are to understand, is proof positive of the exceptionality of the United States because even if the US was directly responsible for these historical evils, that Price has now found purchase in American concert halls is ostensibly demonstrable evidence that the arc of American History bends toward justice.

…that Price has now found purchase in American concert halls is ostensibly demonstrable evidence that the arc of American History bends toward justice.

This Dvořák myth is ultimately inseparable from the legacy of the Western Classical Canon and Price’s place within or without it. “Price’s inclusion in the canon is surely long overdue,” the notes read. And later, on the subject of Price’s String Quartet No. 2 in A Minor “[a]lthough this will be the premiere recording, the Catalyst Quartet looks forward to the day when this work has the plethora of recordings and interpretations that it deserves, just as any other of the great quartets in the cannon [sic] has.” This desire to canonize Price strikes me as an impulse yet again to salvage some institution that otherwise risks becoming obsolete. And it seems at first like a logical fix. If the problem with the Canon is that it’s too restrictive and limiting, why not expand it? Why not open it up to include those we feel are left out? And yet I think this solution misses the point. The Canon, or any canon, is by its very nature limiting and nominally meritocratic. To expand it bit by bit is an exercise in futility, in part because there isn’t some fixed list of works or composers that actually constitute a Singular, Sole Canon, but more to the point, because a canon must be restrictive. There can only be a canon if there are also apocrypha. And if we’re able to admit that our understanding of the criteria for a canonical work or an apocryphal one change and evolve over time, it’s almost a certainty that if there is still a Classical Canon a century from now, we will still be talking about how and why it needs to change. It strikes me then as a dated and flawed way to try and understand a body of texts to begin with. If our current way of thinking excludes Price’s music, despite all evidence pointing to the aesthetic and historical value of these works, then what’s the point of clinging to it in the first place?

I think all of these questions and threads converge at the point of marketing and profitability. Without question, the origins of the Classical Canon have roots in those same 19th century nationalist projects discussed earlier, but it’s hard to imagine regional symphony orchestras in the 21st century continuing to program Brahms symphonies out of some belief in the superiority of Germanic symphonic development or something. Instead, I think some calcified versions of those cultural values intersect with the razor-thin profit margins orchestras or chamber groups contend with to create a cruel, only obliquely racist feedback loop in which the works orchestras want to program are the ones they know audiences want to hear and the works audiences want to hear are the ones they already know or at least have heard of. The Canon, in the 21st century anyways, is as much a marketing phenomenon as the “rediscovery” of Price’s work. And in order for new works to enter this marketing scheme, they’ve got to have a good hook. Whether for good or for ill, Price’s works were granted just such a hook in 2009.

My point in this review is not to set out a line-by-line list of grievances with the prose in the Catalyst Quartet’s liner notes, but instead to use the release of these important recordings as a lens into the broader questions of how and why classical music can be made meaningful for audiences in the 21st century. There is no question that the love Florence Price’s music is finally receiving from a lot of mainstream classical sources and ensembles is long-overdue and well-deserved, but I hope that by taking stock of the way we frame this love and perhaps what that framing says about our own cultural assumptions and desires, we might find a way to move beyond limiting, proscriptive programming practices that will create the Florence Prices of our own time.

From New Focus Recordings

Eric Nathan’s ‘Missing Words’ Speaks When Language Fails Us

On January 21st, 2022, New York-born composer Eric Nathan released an album anthology of his six works titled Missing Words. Each composition consists of multiple movements, all with titles derived from newly devised German portmanteaux, which can be found in Ben Schott’s 2013 inventive dictionary Schottenfreude. With no single movement spanning over seven minutes in length, each episode feels like a vignette, a glimpse into a moment in time felt profoundly by the composer, then dictated into musical form.

Glossing over the societal context predating the album’s release seems foolish to this author, as I believe these pieces work best within the communicative styles born from and fostered by the pandemic. In a world where effective and concise verbal communication is more important than ever due to the isolated nature of interpersonal relationships—whether between two socially distanced best friends or the legion of professionals separated by the screens in their individual home offices—cultural phenomena has revolved around filling the gaps left by language and its limitations. Linguistic analysis pervades social media, however casually or formally. These analyses range from reactions to and repercussions of the divisive political rhetoric that dominates US media, to a deconstruction of Generation Z colloquialisms like “no because” by TikTok user @abrahampiper, to the poignant podcast episode of Krista Tippett’s On Being with poet Ocean Vuong where he breaks down the frequency of violent words in slang among English-speakers.

After seeing such a widespread focus on linguistics and the question of how language affects social interaction, Dr. Nathan’s work feels particularly timely, pulling from source material that seeks to address missing words in the English language as he fills gaps in verbal communication transcending beyond all language, through the emotive medium of music. To say Nathan’s work encapsulates that disparity is an understatement. As Ben Schott remarks in his lovely foreword to the album:

“Schottenfreude exists because when English is exhausted, we turn to German.

“Missing Words exists because when words are exhausted, we turn to music.”

One element captured in this complete body of work is the idea of the literal versus the figurative. The album booklet actually includes two separate track listings—one with the portmanteau movement names and the subsequent literal translation of the compound word breakdown (i.e. Herbtslaubtrittverginügen translates directly to Autumn-Foliage-Strike-Fun), the other giving a definition in addition to the breakdown (respectively, the definition for the prior example being “Kicking through piles of autumn leaves”). While listening to the album, I sought to interpret each track three separate ways:

- Through identifying the individual elements given in the deconstructed compound word translation,

- By listening through the lens of the comprehensive definition given for the movement,

- And combining the two concepts into one cohesive musical form, using the literal elements as thematic material informed by the figurative translation of the word given in the definition.

By doing this, I found an auditory experience that I related to on multiple levels, intellectually and emotionally, while giving myself time to sit with how those words in different contexts evolved within the musical space. I’d advise any listener to follow the same process; I found catharsis in some of my own personal baggage provided by these past few years, particularly with Missing Words VI.

Featuring incredible performances from these ensembles—the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, the American Brass Quintet, Parry and Christopher Karp, the International Contemporary Ensemble, the Neave Trio, and Hub New Music—each Missing Words compilation follows a different instrumentation, which gives the entire album a distinct sense of variety between the meanings of the individual pieces. While the album’s thirteen-page booklet contains the aforementioned foreword and a brilliant in-depth musical summary analysis provided by composer and Boston Symphony annotator Robert Kirzinger, here are descriptions of some of my favorite moments of the album based on the definitions denoted in the booklet:

Missing Words I, Mvt. III “Fingerspitzentanz” (Fingertips-Dance)—meaning “Tiny triumphs of nimble-fingered dexterity.”

Call and response motifs between individual players highlight technical flexibility in idiomatic challenges for each instrument, yielding a quietly victorious end to the first work in the series. As a bassoonist myself, I was drawn toward the prowess of the woodwind performers: Amy Advocat on clarinet and Ronald Haroutunian on bassoon.

Missing Words III, Mvt. III “Straußmanöver” (Ostrich-Maneuver)—meaning “The short-term defense strategy of simply denying reality.”

The final moments of this movement with the cello in its highest tessitura gave me complete pause. Parry Karp’s mastery of the instrument’s range steals the show, and the vulnerability he supplies in contrast to the stubborn piano chords interjected by Christopher Karp lead perfectly into the contrasting frenzied and charged nature of the following concluding movement.

Missing Words VI, Mvt. V “Witzbeharrsamkeit” (Joke-Insistence) III—meaning “Unashamedly repeating a bon mot until it is properly heard by everyone present.”

A prevalent theme throughout the entirety of these pieces is the infusion of multiple genres, including motifs provided in the nineteenth century by Ludwig van Beethoven. With the focus of this piece being placed solely on human interaction, this third iteration of “Witzbeharrsamkeit” draws attention to the emotional isolation of an individual. One can hear Alyssa Wang’s violin instigating the overdrawn-out joke, while the rest of the performers conspire to avoid joining by playing together in a juxtaposing compositional technique. Traditional vs. Contemporary. Retired vs. Relevant. With the context that this specific piece was written during the lockdown of 2020, the alienation of the violin in turn becomes a place of solace for the listener.

As this is a review of the full album, the masterful production and editing also need to be addressed. No moment felt out of balance, and every audio engineer involved was able to capture the stark contrasts in timbre in dynamic, allowing for an engaging, visceral audience experience. In addition, Denise Burt’s minimalist and tranquil album design puts the focus right where it needs to be—on the words, and even more importantly, on what lies between them.

In conclusion, this standout body of work from Eric Nathan is a perfect addition to the pandemic-influenced artistic canon. Even outside of that narrative, the album still succeeds, providing an easy-to-follow linear progression through each Missing Words vignette, woven together by an omnipresent thread—the question of how to bridge the gap of language with abstraction through art. On that note, I will leave you with one final quote by Hans Christian Andersen that this work embodied in my mind since my preliminary read of Ben Schott’s foreword:

“Where words fail, music speaks.”

With that in mind, Dr. Eric Nathan’s work speaks from a place where even Ben Schott’s profundity with words cannot truly go.

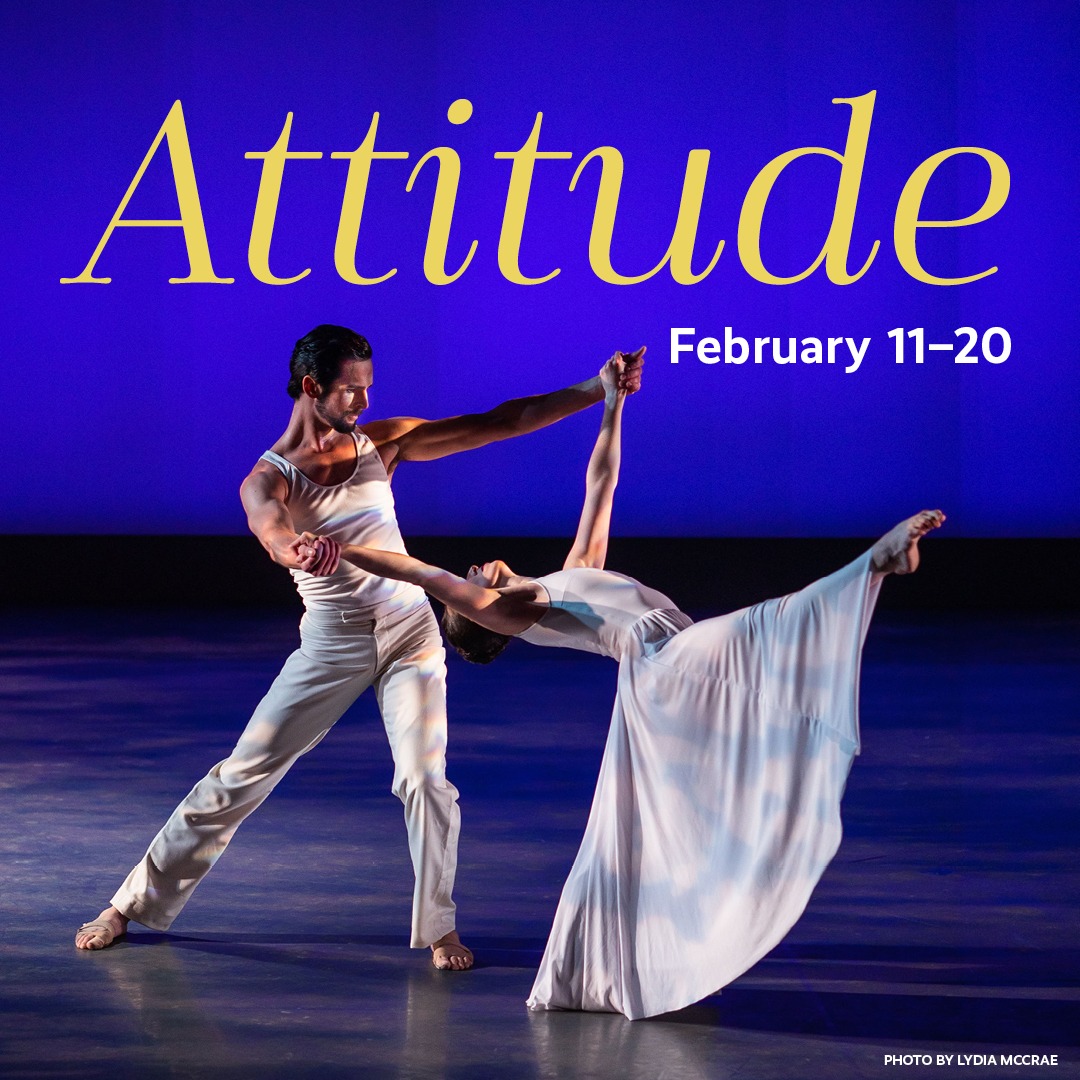

In Nashville Ballet

“Attitude’ Opens Next Weekend

Nashville Ballet will kick-off the new year with the return of their annual Attitude series

February 11–20. Staged on-site at The Martin Center for Nashville Ballet, this year’s production will give audiences an up-close look at award-winning works by renowned choreographers. The performance will feature Nashville Ballet Company dancers and Lockeland Strings, who will perform live during Mollie Sansone’s Fortitudine. Nashville Ballet Company dancers will perform Twyla Tharp’s Nine Sinatra Songs, Val Caniparoli’s Tutto Eccetto Il Lavandino (everything but the kitchen sink), and Company Dancer Mollie Sansone’s newest work, Fortitudine. Each performance will include complimentary valet parking and cocktails at intermission receptions with Nashville Ballet Artistic Staff.

Nashville Opera

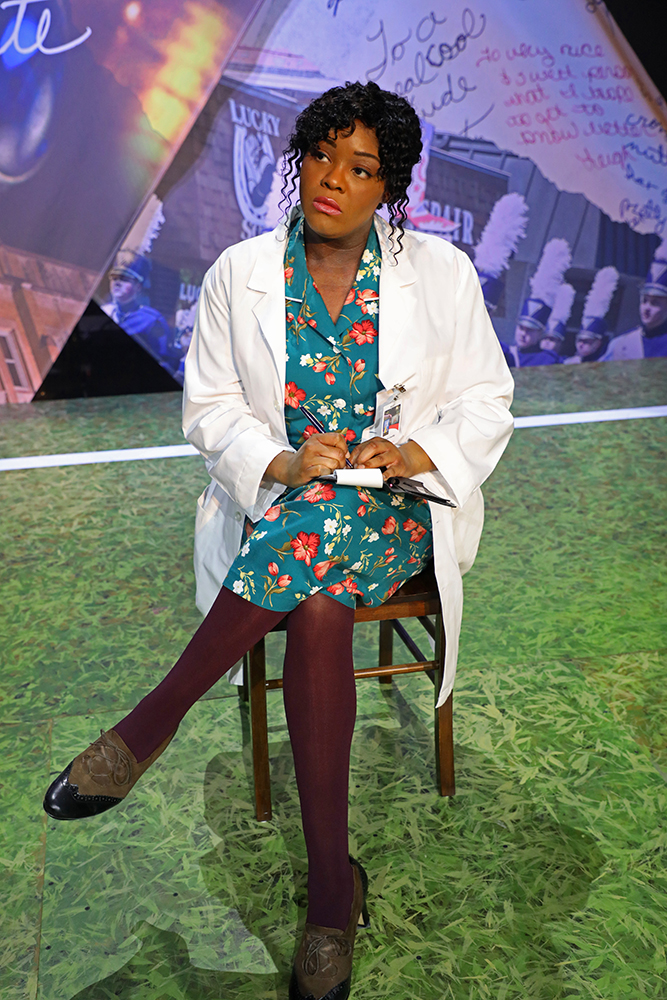

Nashville Opera Kicks off its 2022 Season with ‘Favorite Son’

At the Noah Liff Opera Center, each time one enters, who knows what the stage and atmosphere will be. For the recent production of Marcus Hummon’s “Favorite Son,” an old radio broadcast of a football game is piped into the theater as the audience of opera stalwarts find their seats. Billed as a folk opera, the hour-and-change run time hit many comfortingly familiar story beats with a bit of country flair, even as the Grammy-winning composer straddled genres and themes.

The story first opens at an Episcopal high school, where several Americana country tropes are introduced: senior football star Chris, his sweetheart Kate, football coach/parental proxy aptly named ‘Father Coach,’ and a brief series of events leading up to ‘the big game’ and celebrations thereafter. Right out of the gate, John Riesen’s (Chris) voice filled the theater with a welcoming richness in the lower register. It continued to bloom further throughout the story in more grand tenor-y moments, as in the anthemic chorus of the eponymous “Favorite Son” song. Darrell Scott (Father Coach) tackled many twisty melodic lines during several recitatives modeled after Anglican chant. Emma Grimsley as Kate complemented Chris’s presence with several tender duet sections throughout, but was sadly underutilized overall. The role’s small vocal range and rare solo moments despite being a ‘main’ character belied the true capabilities of Emma as a performer. This held true as well for Jennifer Whitcomb-Oliva’s character (Chris’s doctor at an asylum during the second half); the role’s existence provides additional opportunity for Chris to announce his feelings and thought processes, but not much else.

Of particular enjoyment, especially during the first half, was the ensemble comprised of students from Belmont University’s musical theater department. Serving at times as the football team, bar patrons, and later asylum residents, their choreography incorporating step dancing and body percussion had great visual effect. Coupled with Hummon’s tongue-in-cheek rewrites of conventional hymns to be about defeating opponents on a football field or taking on the challenges of finding success in the wider world, the ensemble’s chances to shine early on kept the energy high and generated quite a few laughs in the opening few numbers.

After a 15-year jump in time, the plot settles down into a more somber tone as Chris returns to his hometown, feeling he has never really found a footing in the world after his peak success in high school. Without fully giving away any twists in the story, it comes to light that some events may not have occurred as remembered, or had been blocked from memory altogether, leading to dramatic realizations and confrontations at the climax of the

show. Where the first few scenes leaned heavily into country & folk elements with imagery of god-sports-glory and a slice of American pie, the latter half of the opera introduced more common musical theatre & opera tropes. Plot points with scenes in an asylum and a cemetery mirror those in The Rake’s Progress, Spring Awakening, or Sweeney Todd. Where it would have been interesting to see a fresh twist on those familiar beats, similar to the

spin on hymns, recitative, and chant that were presented earlier on, these moments in the show were presented ‘as is’ within the context of the plot, bringing nothing new to the concepts but still eliciting serviceable familiarity.

Kicking off the 2022 Nashville Opera season with a world premiere gives an adventurous flair to the programming, even as the smaller, more intimate scope of the personnel will be contrasted with heftier productions of Rigoletto and Das Rheingold later in the season. Having a small number of leads helped to keep the story concise and focused, further aided by straightforward storytelling during recitatives and plain, unabashedly catchy choruses. The pit orchestra of just five members balanced a meditative quality during lulls with more grooving textures when the moment called for it. Perhaps a bit more orchestration could have behooved the soundscapes, as some synth parts were a marked contrast to the organicism of the core piano-guitar-drums trio. To further the experience of the premiere for attendees, a QR code was offered in the lobby after curtain for patrons to stream the soundtrack again at their leisure – a thoughtful gesture for new music or old favorites alike. At evening’s end, the enjoyment of a live production, new music, a twist on a familiar story, and supporting Nashville arts culture certainly brought life and vitality to all who attended.

The Nashville Symphony

The Band is Back Together! Dvořák, Mozart and Suppé at the Schermerhorn

On Saturday, January 8th the Nashville Symphony returned to the Schermerhorn stage as a complete ensemble to give a rather excellent concert featuring Franz von Suppé’s Poet and Peasant Overture, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K. 491 and Antonín Dvořák’s Symphony No. 8 in G Major.

Not very well known today, Franz von Suppé was one of the glitterati on the 19th Century Viennese landscape. Born to Austrian civil servants, he spent his youth studying law with music as a side occupation. In his youth he met Rossini, Donizetti (a distant relative) and Verdi while a law student in Italy. After his father’s death in 1835, his mother brought her teenage son back to Vienna, the city of her birth. There he took up composition in earnest focusing especially on opera. His premiere Das Pensionat was the first authentic Viennese operetta, written in response to Offenbach’s French version. The creation of the Viennese Operetta would be his primary claim to fame.

A master of characterization, his music features a light, fluent style that is delicate and descriptive—it is this style that allows his overtures to retain their toehold in the repertoire. His Poet and Peasant Overture premiered in 1846 and features a beautiful solo for cello, played in Nashville with extraordinary grace by our new Assistant Principle Cellist Una Gong. (The melody seems quite closely related to the melody from “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad). This pastoral is abruptly followed by a fast moving and exciting theme in the strings that leads to a graceful and nostalgic Viennese waltz—it’s as if Popeye has met Violetta. In the context of so much gloom and doom, (the pandemic, the anniversary of the January 6th Insurrection, etc) opening the concert with the exciting and escapist high Viennese music was a stroke of genius. When I closed my eyes I could almost image myself at the Musikverein!

In the modern era the speed at which classical composers were forced to work is often forgotten. Mozart’s 24th Concerto was written within just three weeks of his 23rd, K. 459 in A minor. This is even more striking given the fact that he was also reworking Idomeneo for Vienna during the same period. Both concertos show Mozart’s writing at its highest form—breadth and fluency in structural conception, a solo part that is more collaborative and concerted than competitive. Further, it was written for a large (for Mozart) orchestra—it is his only concerto with both oboes and clarinets. And, as Maestro Guerrero noted before the performance, a number of the instruments get their own solo moments.

The key of C minor is also odd for Mozart, as is the mood—the piece begins with a descending line that seems to plead in despair. This is followed by a different, but equally pleading line in the piano, played by American Pianist and 2015 Tchaikovsky Silver Medal winner George Li with a respectful reverence. His light and gentle approach on Saturday evinced a delicate restraint that is rather rare in a pianist whose Rachmaninoff has been described as “absolutely stunning.” The wind section of the Nashville Symphony did themselves proud in the second movement’s episodes.

After intermission, the orchestra returned for a performance of Dvořák’s Symphony No. 8, a rather optimistic work for the Czech composer. The nationalistic Bohemian content of this piece might likely have been one of the reasons that Jeannette Thurber brought him to the new world to direct her National Conservatory. Donald Francis Tovey’s biting criticism of the composer is also not without its merit: “Dvořák’s phrasing was primitive, Bohemian, and childlike before he went to America. It is primitive, Bohemian, and childlike to punctuate your phrases with chuckles; and the pentatonic scale pervades folk-music from China to Peru.” That said, Dvořák’s nuanced orchestral color and clarity of formal design makes one cry “Humbug” at old Tovey.

The first movement’s exposition began with a broad lyrical theme, darkly scored in the cellos, horns, clarinets against a trombone counterpoint in G minor. Eventually a bright bird call emerges in the flute and piccolo, sparkling in the hands of Erik Gratton (flute) and Gloria Yun (piccolo) and remarkable when in dialogue with Nashville’s eloquent oboists Titus Underwood and Leslie Fagan. Maestro Guerrero was in fine form throughout the evening, and this movement actually saw his feet leave the podium during the development’s mighty storm. (the Suppé had brought him from his feet as well). The slow second movement continued with the pastoral idea with its own thunderstorm.

Dvořák’s third movement left the beauty of the Bohemian landscape for its ballrooms with a wonderfully melancholy waltz offset by a naïve central section. Here the NSO positively rollicked. The piece ended with a theme and variation movement that was so incessantly cheerful you could see Maestro Guerrero’s bright, joyous, dependable and disarming smile mirrored back by what seemed to be the entire audience when they leapt to their feet in ovation. Despite the masks, the pandemic and the constant fear, Nashville once again found a way to get lost in the music. Welcome back to our dear symphony, we’ve missed you!

New from OEHMS Classics

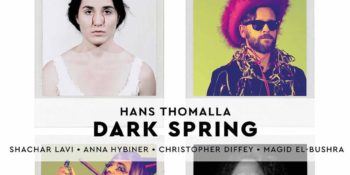

Thomalla and Clover’s ‘Dark Spring’: Will You Listen?

In all honesty, I received the assignment to review this opera in late September. That’s when I should have listened, but I didn’t. Life got in the way. Would it really have mattered? Would you have listened? Would you have watched? Do you, the audience, now shutter at the thought of being passé? I doubt it. This opera is now months old; deal with it.

Does anyone still care about new opera? In front of you is Hans Thomalla and Joshua Clover’s new opera Dark Spring. Will you listen? It runs an hour and a half… that’s probably the length of your favorite movie. Forrest Gump isn’t much longer. The link can be found below. Will you watch it? Can you truthfully say that you like opera that much?

Regarding the opera, it’s brilliant. From the downbeat the mastery of orchestration that Thomalla wields is evident. Throughout, he provides the right instrument/instruments for the moment. Not only that, but he is supremely egalitarian in his orchestration; never giving you too much at once. This skillset, rare in the day of “do it or bust opera”, is especially marked in its relation to piano (particularly the extreme ranges of the instrument). This truly natural compositional grace and patience makes

its way to the high brass, strings, and percussion. Bernstein-esque in all aspects, the orchestration creates its own tight-knit and knitty-gritty orchestra; this, above all, sets the work apart.

Within any opera, the voice part is sacred. The counterpoint between the voices is beyond mention. It is so well done that I won’t review it; you have to listen. If you don’t, you don’t. The link is here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cfo9OfwQMHY.

When I started writing reviews someone told me the most negative thing I could do was leave something unsaid. My concision is a compliment. The composition, execution, and performance are unparalleled; I have nothing negative to say. Congrats to Thomalla and Clover. Will you listen?