New from New Focus Recordings:

Pathos Trio – When Dark Sounds Collide: New Music for Percussion and Piano

The Album

When Dark Sounds Collide: New Music for Percussion and Piano consists of five tracks, each of which is a collaboration with a different composer. The composers were encouraged to craft a piece in their voice, resisting the temptation to write what one might think Pathos Trio expected or desired. The ensemble submits that this has culminated in an album which, “combie[s] aesthetics of contemporary classical music with the ensemble’s interests in dark, heavy, dense sounds drawn from other genres of music such as alternative rock, cathedral music, minimalist music, electronic synth-wave, and more. As a result, each work on this album creates raw, edgy, and powerful soundscapes that will engage audiences in both mainstream and classical/new music scenes.”

The composers were encouraged to craft a piece in their voice, resisting the temptation to write what one might think Pathos Trio expected or desired. The ensemble submits that this has culminated in an album which, “combie[s] aesthetics of contemporary classical music with the ensemble’s interests in dark, heavy, dense sounds drawn from other genres of music such as alternative rock, cathedral music, minimalist music, electronic synth-wave, and more. As a result, each work on this album creates raw, edgy, and powerful soundscapes that will engage audiences in both mainstream and classical/new music scenes.”

The five commissions featured on this album are strong, making a convincing assertion that the medium of two percussionists and piano is viable and should continue to be explored and further developed. Not as convincing is the narrow emotional scope through which listeners remain for much of the album. While the works are powerful on their own, the pacing of the release can feel stagnant, at times. That does not suggest, however, that a superficial happiness is desired, but rather, a courtesy offered to listeners to address that the nature of a project that brings together five different visions, as opposed to a tightly unified story woven from a single artistic voice, does have challenges when considering the composite. Still, When Dark Sounds Collide: New Music for Percussion and Piano is recommend listening. I trust that those who do listen will be eagerly awaiting the next release from Pathos Trio.

The Ensemble

With a mission that, “aim[s] to bring adventurous music to audiences through collaborations with young, living new music composers,” Pathos Trio brings together the talents of two percussionists and a pianist. The group recognizes the serious responsibility of developing future generations of collaborative performers. To aid in this endeavor the ensemble offers clinics focusing on the administrative and production aspects of music, performance masterclasses, open rehearsals and demonstrations, and educational performances and workshops.

The Members

Alan Hankers, piano

Alan Hankers is an award-winning composer, sound designer, and pianist who has written music for television, film, video games, and concert halls. His music invites listeners to experience soundscapes of great depth and variety that draw on his diverse musical background. Hankers currently teaches music theory courses at Montclair State University, having previously taught at Stony Brook University, where he earned his Ph.D. in 2021.

Felix Reyes, percussion

Born in Brentwood, New York, Felix Reyes is Managing Director of Pathos Trio and is a freelance percussionist living in Brooklyn, New York. Graduating with his Master’s in Percussion Performance from Bowling Green State University, Felix studied percussion under Dr. Daniel Piccolo and marimba specialist Dr. Isabelle Huang. Furthering his emphasis on marimba performance, Felix also received a Diploma in Marimba Performance at the Toho Gakuen School of Music in Sengawa, Japan, where he studied with marimba legend/virtuoso Keiko Abe.

Marcelina Suchocka, percussion

Born in Bialystok, Poland, Marcelina Suchocka is a fourth-year Percussion Fellow at the New World Symphony. She has performed as an extra/substitute percussionist with the Chicago Symphony, Kansas City Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Detroit Symphony, and Utah Symphony. Ms. Suchocka graduated from Manhattan School of Music, where she completed both her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees under Christopher Lamb, Duncan Patton, She e Wu, Kyle Zerna, Patsy Dash and Douglas Waddell.

The Tracks

1.) Fiction of Light

Composer: Evan Chapman

10:02 minutes

The album opens with Evan Chapman’s minimalist, electronic style rock work, Fiction of Light. This piece has a meditative quality. The aesthetic feels both current and accessible, while still being able to retain an haute couture personality. While I am not aware of the piece being programmatic, it sounds as if the listener is experiencing the vulnerability and emotion that often accompanies delivering a eulogy. Then, with a surprise punctuation and shift in character, the listener is met with the final section of the piece that ultimately brakes towards its conclusion.

Evan Chapman is a percussionist, composer, and filmmaker based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After receiving his Bachelor of Music in Classical Percussion Performance from the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, he has gone on to build a prolific and unique career by seamlessly blending multimedia and contemporary music. As a filmmaker, Chapman – alongside Four/Ten Media business partner Kevin Eikenberg – has become one of the most in-demand collaborators in the contemporary classical world.

2.) Prayer Variations

Composer: Alison Yun-Fei

10:20 minutes

Canadian composer Alison Yun-Fei Jiang explores the intersections of cultures and genres by drawing inspirations and influences from an array of sources such as East Asian aesthetics, Chinese opera, natural landscapes, Buddhism, art, film music, popular music, and literature, all while creating musical narratives and experiences in a lyrical, dynamic, and storytelling nature.

Her contribution to this project, Prayer Variations, has been characterized as a solemn and gloomy work that creates a dialogue through churchlike melodies. These melodies are initially expansive and obtuse in their durations, but they soon summon energy as the piece develops with faster successions of metallic percussion sounds communicating with contributions from the piano. Interjections from membrane percussion instruments develop the piece further, confirming and leading the listener to the next structural section that is host to new arpeggiated discoveries in the piano. The work returns to its opening contemplative mood, as if to remember its defining tenet.

3.) Delirious Phenomena

Composer: Alyssa Weinberg

8:18 minutes

Delirious Phenomena should be the first single highlighted from the album. The physical demands and coordination required of this piece add an

expanded element of interest. Four/Ten Media effectively captures the choreographic logistics of three musicians producing sound from a single instrument -watch here.

The piece features heavily percussive prepared piano. Grooves are established from both mallets and performer’s hands striking different parts of a piano, while the manipulation of the keys and strings produce harmonic offerings. In a contrasting middle section, the strings of the piano are manipulated differently to produce a drone-like quality. Members of Pathos Trio even offer their voices to enhance this portion of the sonic landscape.

As is experienced throughout Delirious Phenomena, Dr. Weinberg uses color, texture, and gesture to channel big emotions. She is fascinated with perception and loves to play with form, subverting expectations to create surreal scenarios, often in dreamy, multidisciplinary productions. Weinberg currently teaches composition at Montclair State University and Juilliard Pre-college. She is also the Founding Director of the Composers Institute at the Lake George Music Festival.

4.) Oblivious/Oblivion

Composer: Finola Merivale

12:00 minutes

Finola Merivale is an Irish composer of acoustic and electroacoustic music, currently living in New York City. She is a Dean’s Fellow at Columbia University where she is pursuing a Doctor of Musical Arts in Composition, studying with George Lewis, George Friedrich Haas, and Zosha Di Castri. Merivale reports that themes running across her music include climate change, inequality, and a sense of place – both real and imagined.

The place in which Oblivious/Oblivion exists has been referred to as a place that traverses a dimension that spans from calm to frantic. Of the piece, Merivale writes:

The terror of climate change is preoccupying so many of my thoughts, and is therefore the focus of most of my current music. I am devastated at the loss of life that is occurring daily – humans and other species. I am angry at how little is still being done. Too many people are still oblivious, as our beautiful planet sinks into oblivion.

Listeners may be challenged from the metallic smack that opens the work and intermittently startles the otherwise rather pensive, contrasting counterpoint. Metallic smacks and moans evolve into break drum outbursts that seem to have the intention of polluting an already unsettled melody. This tension leads to an unmistakable destruction nearly halfway through the work. After the initial shock of this destruction is absorbed with the aid of silence, an avalanche of siren sounds fades to another moment of silence. A final sonic push doesn’t seem to fully climax, but instead feels truncated. This uncertainty is accompanied by a period of extended silence that is an artistically deafening way to close the piece. Uncomfortable and powerful. Important.

5.) Distance Between Places

Composer: Alan Hankers

10:26 minutes

Perhaps the beneficiary of home field advantage, composer and Pathos Trio member Alan Hankers closes the album with his work, Distance Between Places. Described as a heavy hitting finale, Distance Between Places sounds as though it is organized into distinctive tableaux.

Building from silence over multiple minutes, the listener is treated to an assumed compound-meter jam session, elusive in its beat groupings, but nonetheless driving. This is juxtaposed to a desolate middle section that consists of a few short solo instrumental monologues. These solo voyages are combined to signal the end of this section and the start of the closing portion of the piece.

The closing portion of the composition seems to take influence from the two previous sections through which it has travelled. Equally influenced by the jam session and short monologues, the final section becomes a greater sum of both of these parts, yet unique unto itself. The listener will have to decide whether the composition suggests satisfaction or contempt with respect to the final ‘place’ where one is left.

Coda

When Dark Sounds Collide: New Music for Percussion and Piano is the first commercial recording from Pathos Trio. This album was released on the New Focus Recordings label in March 2022. Additionally, Four/Ten Media has produced accompanying music videos for each track on the album. One can purchase a copy of this release through the ensemble’s website or stream the work on Spotify.

Nashville Jazz Workshop Presents Jazz on the Move

The Jazz World’s Precious Metal: Horace Silver

The five jazz pros were mined from differing ores—cool jazz, smooth jazz, bebop, rock, blues—but together they gradually produced a fine alloy that honored the legacy of Horace Silver, pianist extraordinaire. Silver’s legacy as one of the cofounders of hard bop, a style that melds the dissonance and rhythmic energy of bebop with the softer genres of blues, gospel, and soul, was well represented Sunday afternoon at a 3 pm program collaboratively hosted by the Nashville Jazz Workshop and the Frist Art Museum. This is part of NJW’s Jazz on the Move series that places jazz in a variety of venues around Nashville.

Born in Connecticut, Horace Silver, who died in June 2014, first heard jazz at a county festival when he was ten years old. He was mesmerized by the sharp-dressing, tight-playing Jimmie Lunceford Band and decided that’s what he wanted to do. After some training, he moved to New York where he frequently played at Birdland, one of New York’s most significant monuments to jazz. As part of the “put-together” bands—local musicians who warmed up the audience for the headliners—he was able to hear musicians like Art Tatum and Teddy Wilson, and play with musicians like Art Blakey, Stan Getz, and Bud Powell. Through a record-collecting girlfriend, he was introduced to Thelonious Monk and became a lifelong fan.

Unusually, once signed with Blue Note Records, he stayed with them for nearly thirty years. In an interview for Minneapolis Public Radio, he attributed this longevity and his success as a performing musician to the fact that he didn’t drink, smoke, do drugs, or show up late. Later, he left to start his own label, Silveto Records for music that was growing more spiritual, more metaphysical, incorporating singers. He kept his Emerald label for the more typical jazz instrumentals that had established his reputation.

The Frist’s well-attended event, a fusion of concert, bits of history, and verbal program notes, educated and entertained in nearly equal measure. From the piano, Pat Coil provided valuable little nuggets of history to an enthusiastic audience, bringing the backstory of the works to life with relaxed humor. One missing element was more information on how each work was representative of Silver’s style. But some of that came through Coil’s playing style for each piece.

The band consisted of a rhythm section with Coil, an MTSU professor who has played with artists as diverse as Natalie Cole, Barry Manilow, Travis Tritt, and Woody Herman, on piano; Roger Spencer, co-founder of NJW and adjunct at Vanderbilt’s Blair School of Music who has done stints with Les Brown and His Band of Renown, Rosemary Clooney, and Tony Bennett, on bass; and guest artist Chester Thompson, a veteran of fusion having played with the famed Weather Report and Genesis, on drums.

On horns, trumpeter Emmanuel Echem, a Belmont graduate who has performed or recorded with Kirk Franklin, Boyz II Men, LeAnn Rimes, and one of my favorite lesser-known bands, Dumpstaphunk, which features members of the famed Neville musical family out of New Orleans; and Don Aliquo on tenor sax, another MTSU professor that has performed with Gary Burton and Roger Humphries. His 2019 album The Innocence of Spring was nominated as one of the Top 10 jazz recordings on National Public Radio.

Initially, the band members kept to their individual origins. In “Nica’s Dream,” for example, Thompson, the drummer was a bit heavy on the snares, perhaps part of his rock history, while Coil and Aliquo, piano and tenor sax, repped cool jazz, à la Dave Brubeck and Paul Desmond, respectively. Trumpeter Echem showed some of the rough edges sometimes found in Miles Davis, while Spencer, the bass player stayed somewhere in the middle. But there were hints of better to come.

In “No Smoking,” Spencer showed a more assertive walking bass, to complement Coil’s well-placed splashes of chords, while Thompson had a nice way with syncopation on the ride cymbal. In “Gregory is Here,” a song written for the birth of Silver’s son, Coil set up the Cuban son clave rhythms into a sweet groove, reminding me of the Buena Vista Social Club, a group of elderly Cuban musicians whose careers were revitalized by American guitarist Ry Cooder. In this laidback work, the trumpet and sax finally began to blend.

Following Coil’s lovely solo intro with its sense of Debussy harmonies and Silver melodies, Thompson’s nice brushwork and Spencer’s casually strolling bass blended with Aliquo’s cello-like timbre in Silver’s bluesy “Peace.” When Echem joined, his trumpet timbre matched the rest and here, these talented individual professionals became a band. Once they found the right formula of their constituent parts, the mix was stable for the rest of the show, moving as a unit from style to style.

For example, “Nutville” was next, a high-energy, hardcore bebop piece. Coil said he didn’t know where the name came from but to me, it clearly has some of the drive and unexpected humor of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie’s “Salt Peanuts.” But in Silver’s signature style, there’s a fusion of close dissonant harmonies for the horns and Latin groove, in this case the Brazilian trecillo rhythm. It was also the best arrangement of the day. Starting together, they drop down to a trio of sax, bass, and drums, then everyone reenters before a driving vamp leads to the one extended drum solo of the day.

It was worth the wait. Thompson took us on a world tour beginning with some spicy work on the crash cymbal, slowing down and softening into a delicate, almost Asian sound formed from the metallic sounds of drum rims and cymbals, before building back up with indigenous sounds of South America emphasizing the tom-toms, and bringing it on home to American jazz.

The final work “Song for my Father” is, as Coil noted, one of Silver’s best-known and most frequently covered. Like Monk’s “Round Midnight” and Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm,” several backing tracks of it are available on YouTube for aspiring players who want to learn iconic works. Its basic pattern was apparently borrowed for Steely Dan’s “Ricky Don’t Lose that Number,” increasing its renown. Sunday’s rendition proved to be a nice fusion of cool jazz harmonies, Brazilian samba rhythms, and standard pop timing. As Silver once said, “Why make it difficult for listeners to hear?”

In keeping with Silver’s ethos, this gorgeous arrangement was definitely easy on the ears. It was dedicated to his father, an immigrant from Cape Verde (a set of islands off the coast of northwest Africa) and his father’s love of a variety of musical styles, including the Portuguese folk songs he sang to his son. The much-welcomed extended bass solo gave plenty of time to relax into the mood. The trumpet eased right in, the sax’s lovely tone balanced chill with driving chromatic transitions, while the drum did his best hi-hat work, dropping in a few light bebop accents, as the pianist maintained a languid tropical style with just a taste of boogie-woogie, one of the styles that influenced the star of the show, Horace Silver. May he rest in the peace of his music.

A Home for Jazz in the Music City:

Welcome to the Nashville Jazz Workshop

Lori Mechem comes from a small town in Indiana, but there’s no midwestern twang in her voice. And there’s no snarky vibe from her time in LA or Southern drawl from her 25 years in Nashville. Instead, she’s got a laidback chill redolent of late-night whiskey after a satisfying gig, a rhythmic cadence much like Billie Holiday, that seems like it’s lazing along, but is always right on time.

But that chill belies the blazing determination to keep a light on and a door open for Jazz in Nashville. Co-founder of Nashville Jazz Workshop (NJW), with husband Roger Spencer, she has been a moving spirit for building a spiritual home for Jazz in the Music City. The child of musical parents who owned a music store, her early years encompassed professional work in both jazz and musical theater. Once out of college, she spent serious time in what she calls the “cutthroat” life of a gig musician in Southern California. Tiring of the grind, she and a Nashville-based flight attendant friend swapped places. Lori and Robert moved to Nashville; the friend moved to LA.

It was clearly meant to be. The warmth of Southern hospitality resulted in a space, and even more, a home for jazz lovers or all ages. As she proudly declares: “There’s something for everyone—anybody can take classes, anybody can come to concerts.” She points to the family atmosphere where many of the teachers remain for years, many students become teachers, and many of the people involved in a variety of capacities share their major life milestones with NJW.

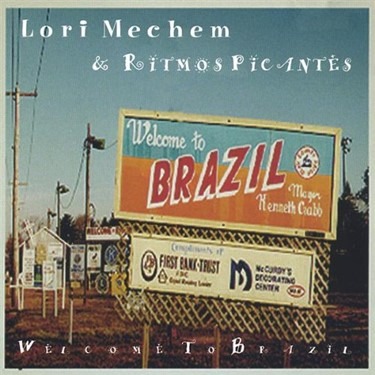

While forming this stable jazz family, Lori hasn’t neglected her own musicianship. She has released nine albums, many with a decidedly Brazilian bent. When asked how a small-town girl in Indiana fell in love with Brazilian music, I could hear the shrug, part of her relaxed persona: “I just liked it. I heard Sergio Mendes and especially [Carlos] Jobim. We even have Jobim classes.” But with a bit of tongue-in-cheek humor, Welcome to Brazil, the first CD with her Ritmos Picantes [Spicy Rhythms] band, featured a photo of Brazil, Indiana on the cover.

Although NJW’s Cuban Ensemble represents yet more Latin influence, North American classics are also part of the mix. For the past two years, she has recorded over 2900 tracks to accompany NJW’s “The Great American Songbook” series. For those who might not know, The Great American Songbook is a “loosely defined canon of significant early-20th-century American jazz standards, popular songs, and show tunes,” including works like “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “It Don’t Mean a Thing (if it ain’t got that Swing)” encompassing writers as varied as Al Jolson and Duke Ellington When Covid hit, NJW’s creative thinking resulted in successful solutions.

Via ZOOM, family members of famed American songwriters reminisced about musicians like Hoagy Carmichael and Peggy Lee. They’ve had participants from all but four US states. ZOOM has also allowed for access to performers whose positive experience with NJW events has led to upcoming in-person performances by cabaret singers from New York City. Bimonthly performances, snappily titled “Snap on 2 and 4” continue, along with one-shot masterclasses, 6-week courses, and more for all ages. But, as the old folks say, the “all ages” part is “more than a notion.” Jazz AM offers delightful Saturday morning interactive experiences for kids, including puppet shows. Lori’s voice lightens as she recalls pleasant memories of children squealing with joy as they learn about artists like Bessie Smith and Charlie Parker.

Forthcoming events for July 2022 include an online Jazz masterclass with drummer Chester Thompson of the renowned jazz-fusion band Weather Report and the hit rock band Genesis (ZOOM, 11–12:30, July 16); “Life and Music of Horace Silver” part of the Jazz on the Move series that features lecture-performances at varied venues (3 pm, July 17 at the Frist); the debut of Juilliard student Tyler Bullock and his Quintet (in person or streamed live: 7:30pm, Saturday, July 23 at NJW’s Buchanan St campus); and sax player Rahsaan Barber (7:30 pm, Friday, July 29, NJW). To learn more, donate, or volunteer, see the Nashville Jazz Workshop website.

One of the world’s first spatial neo-classical concept-albums review:

Maison Melody AM/PM by Stephen Emmer

Stephen Emmer; Dutch composer, arranger, and artist, invites listeners to a unique listening experience with his recent spatial neo-classical album entitled, Maison Melody AM:PM. The conceptual album includes diegetic sounds from the composer’s everyday life infused with emotive and hauntingly beautiful compositional works. The album is presented, in what feels like, a cinematic experience from the audience’s perspective with the interplay of both diegetic sounds and underscored material weaving in and out of each other like a continuous film. The work is presented with cutting-edge auditory and technological advances, including Dolby Atmos and Sony 360, to ensure an immersive and three-dimensional sonic experience. The 42 minute work is broken into ten compositions that are reactive to the sounds in the artist’s living environment, often creating a tantalizing and meditative quality. Emmer is successful in capturing the audience’s attention with his seamless transitions between these sounds, compositional material, and modern recording techniques.

Maison Melody AM:PM begins with the ever-so familiar Apple alarm clock, as it crescendos from the background to the foreground. Soon, other sounds are slowly introduced, including those of waking in bed, birds in nature, water running, and footsteps around the home. Notable is the mastery of the mix during this moment. As the footsteps pan from hard left to right, the audience is invited into an immersive sound world. It isn’t until almost the two-minute mark when Emmer presents the first musical element. A piano motive begins, however it seems distant with heavy reverberation which creates the illusion that it is another diegetic sound within the story. The piano motive is then presented again, however, at this moment in the foreground of the mix, thus, differentiating between the diegetic world and the non-diegetic soundscape. Each cue seamlessly fades back into sounds at the foreground with a plethora of environmental sound material including, but not limited to: television sounds, static noise, white noise, cell phone buzzing, doors creaking, telephone ringing, drinks pouring, bubbling sounds, talking, humming, rain falling, birds chirping, clicking, clocks ticking, fire- crackling, various machinery noises, evening nature sounds such as crickets chirping, and an airplane traveling across the distant sky. These sounds are conceptual and purposefully presented in a chronological order, beginning with the artist’s morning routine through to the nighttime.

Scored for piano and small string ensemble, many of the “cues” begin with a sombre and pensive piano motive as strings enter with lush, long sustains or beautiful melodic lines. The piano material is often simplistic in nature, however, it is also incredibly emotive. Emmer is able to create a sense of duality in his piano writing with the collective use of traditional tonal harmony, extended chords, and dissonant harmonic material. Additionally, Emmer’s treatment of the strings is quite versatile. Strings are used for either harmonic support, lush and romantic melodic lines, or as a minimal and textural effect. A plethora of articulation and expressive techniques are presented including portamento, molto vibrato, pizzicato, sul ponticello, and harmonics. Conjunct melodies, legato lines, and sustained pitches are usually presented within moments that are more traditional in tonality, where more complex string writing, such as in quick arpeggios, ostinatos, and disjunct lines, are featured in more dissonant sections. The harmony throughout many of the compositions are digestible for general audiences, with tonally stable progressions. Dissonance is treated with careful consideration and is used sparingly yet effectively, such as in the eighth cue of the album. The piece begins with repeating dissonant chords in the piano, however, it soon becomes more melodic with whole-tone elements, creating a dream-like mood. As the higher register piano begins, strings enter with moments of dissonance, illustrating duality in mood. Diegetic church bells later interrupt the composition and repeat four times before fading back into other diegetic sounds, such as crackling and sounds of cooking, as the strings sustain.

Whether a classical music aficionado, cinephile, or appreciator of innovative sounds and original works, Maison Melody AM:PM presents a unique auditory experience to listeners of all levels. Hauntingly beautiful piano melodies, soaring lush string motives, diegetic sounds, and effective recording techniques, such as manipulating filters, to create ambient soundscapes, all contribute to an immersive audio cinematic experience. The effortless transition between diegetic sounds and composed material is incredibly effective as it guides the audience smoothly between the diegetic world and the non-diegetic soundscape.

Additionally, the artistic decision to mix certain diegetic sounds and composed music in either the foreground or background helps differentiate the two worlds. Endorsed by Dolby Atmos music, the mix of Maison Melody AM:PM is as spectacular as the compositional material itself. Three-dimensional multi-channel soundtracks create a sonically immersive experience between musical and environmental sounds. Before my first listen, I was not sure how I would feel about listening to a marriage of diegetic sounds with composed music for over forty minutes, however, Emmer is successful in creating an intriguing sonic narrative through this interplay by balancing each section perfectly.

Maison Melody AM:PM, was conceived, composed, and produced by Stephen Emmer, while 2021 International Broadcasting Convention (IBC) Innovation Award winner for content creation, Ronald Prent, mixed the album. Additionally, recording engineer Francesco Donadello engineered the project. Maison Melody AM:PM was released on March 25th, 2022 and is available on Apple Music, Amazon Music Unlimited, Tidal, or as a download on Stephen Emmer’s personal website: www.stephenemmer.com

Stephen Emmer is an award-winning composer, producer, and artist hailing from Amsterdam in The Netherlands. He has recorded and written for, performed, and collaborated with world re-known artists including Lou Reed, Chaka Khan, Patti Austin, Leon Ware, Midge Ure, Julian Lennon, Glenn Gregory, Billy MacKenzie, Mary Griffin, Peter Coyle, Claudia Brucken and Martha Ladley, to name a few. Emmer is the recipient of several accolades throughout his career. In 1988, Emmer was the winner of the prestigious Prix de Rome and in March of 2020 was rewarded for his work with the Buma Oeuvre Award Multimedia.

Nashville Opera Presents

Das Rheingold at Belmont

On May 6th, Nashville Opera presented Richard Wagner’s epic music drama Das Rheingold in the Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Belmont University. A not-so-humble expression of former Belmont University President Bob Fisher’s power and influence, the hall is billed as a “…state-of-the-art facility adding another diamond to Music City’s ring of world-class venues.”* It is quite a challenge that Director John Hoomes created for himself with this production, but in many ways it was quite successful.

After a failed production that left him in catastrophic debt in the Latvian (then Russian) town of Riga where he was the city’s opera director, Wagner swore to only write operas of a size and scale that would demand serious financial commitment to the production. Das Rheingold, a three-hour prelude to the great cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, is nothing short of epic, combining and retelling variations of three old Norse and Icelandic myths from the Eddas. These are the same sources from which J.R.R. Tolkien derived his Lord of the Rings trilogy and where Stan Lee derived some of the modern superheroes that seem to be the only thing Hollywood produces anymore (Thor, Loki, etc). This music is the centerpiece of German nationalism (the Nazis loved Wagner) and requires a huge orchestra, giant, godlike voices, and a staging that would stretch the resources of any major Metropolitan company; in this, Nashville did the very best that it could.

In the famous opening scene, 100+ measures of E flat depicting the creation of the world, the “big bang” depicted on the “two story HD video wall.” It was quite fun to hear live, especially with the four Wagner tubas that were brought in from Atlanta for the performance. Throughout the orchestra played well, despite some hiccups at the onset. For example, the prelude began audibly and increased with what seemed to be terraced dynamics as opposed to a more subtle increase. I’m not sure how much of this is due to the score; Maestro Dean Williamson employed Eberhard Kloke’s version of the score with a reduced orchestra. I’ve not been able to see the arrangement, but aurally the stings were difficult to hear often during the evening, even in this ‘state of the art’ hall. Another complicating factor was the darn pandemic. It swung through music city in a vicious way the week before the production and rumor has it that it devastated the ensemble’s ranks with illness just before the production.

As the curtain went up, the Rhinemaidens, (Woglinde, Jessie Neilson; Wellgunde, Danielle MacMillan; Flosshilde, Jessie Neilson) fetching and charismatic in Rhine riverwater blue with matching lipstick, fended off and mocked the loathsome Alberich (Samuel Weiser) with glee. When the gold appeared, everything came together, and their voices blended in a fantastic, glittering delight—a delightful opening frame that returned well at the end. Alberich, with goggles and garb of a minor (perhaps?) sang in incredible voice. His attempted seduction of the maidens was less lecherous than the interpretations that I am used to, but it was a fantastic decision. It humanized him so that we felt for him when Wotan stripped him of his power, justifying to ourselves the reckoning of his terrible curse.

In the next act, we are introduced to the Gods of Valhalla, with their own incredible voices and sparkling costumes. Indeed, costume designer Matt Logan, the designer for Reba McEntire, glitterbombed the Gods with rhinestones and bright, oversaturated colors like an ‘80s era science fiction film (think Flash Gordon). I understand the urge to recognize location in operatic productions, the “mountain giants” with Tennessee beards were great, but do we have to incorporate “Nashvegas” into our high art too? Once, we were called the “Athens of the South,” now, I’m not so sure.

Lester Lynch’s Wotan was remarkable. If Weiser’s voice brought a nuance to Alberich’s character, Lynch brought power, appropriately ruling the hall. In blocking he was constantly moving around and repositioning himself, which, especially in scenes with Loge, seemed to undermine his authority in a comical way. Loge’s (Corey Bix) tenor was well refined, and his comedy hit true, garnering several chuckles from the audience. Wotan and Loge’s conflict of the giants, powerfully sung and shockingly acted at the fratricide by Ricardo Lugo (Fasold) and Mathew Burns (Fafner), “Hort, ihr Riesen!” was stirring and chilling. Ladies Freia (Othalie Graham) and Fricka (Renée Tatum) deserve special mention: Graham’s strident top effectively expressed her fear in capture and Tatum’s rich, round sound brought a warm and youthful vigor to her character’s portrayal. Erda, a strange character, was also brought out well by Gwendolyn Brown who, under Maestro Williamson’s quite slow direction, gave a portrayal that seemed to appropriately exist out of time. Finally, Donner (Joshua Jeremiah) and Froh (Tyler Nelson) were valiant, cocky, and annoying as one would expect while Mime’s bright tenor (Allan Glassman) briefly made me wish we would be watching Siegfried in a couple of days.

In the end it is difficult for me to give an overall opinion of this mixed production. The voices were of tremendous quality and showed innovative interpretations of the classic characters. The company however, seemed a little overwhelmed. As the Gods paraded their way across the rainbow bridge to Valhalla (there is a rollercoaster in Valhalla?) I wondered if Nashville Opera shouldn’t wait until they have a chance to grow a little more, get used to staging productions in the new hall and have the means to support a standing orchestra (instead of re-creating one for each production) before they reach for the sparkle of another one of Wagner’s epic music dramas. One wonders if they had used the same resources for a more manageable German Romantic work, say Weber’s Der Freischütz or Marschner’s Vampyr, one wonders what they might have accomplished. In any case, with this year’s memorable productions of Rigoletto, Favorite Son, and Das Rheingold, Nashville Opera has had a season that would be the envy of any midsize city in the South, Bravo!

*The hall is nice, but another Ryman or Schermerhorn? Nah. You should have seen the way they accosted my wife for attempting to bring a bottle of water in (as the program suggested)!

The Gateway Chamber Orchestra Presents:

Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony

On April 23, the Gateway Chamber Orchestra presented Gustav Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony (No. 2, 1894) in the Mabry Concert Hall at Austin Peay State University, Clarksville. Mahler’s “Resurrection” is a rarely heard masterpiece of epic proportions—a work typical for GCO’s standard performing repertoire. Indeed, the symphony is written for a huge orchestra, chorus, soprano and alto soloists, but the CCO performed Gilbert Kaplan and Rob Mathes’ splendid adaptation for a smaller, lithe orchestra. Yet, under Wolynec’s baton, and even with a reduced orchestra, on that evening Mahler’s enchanting timbral world was manifest with a remarkable clarity, stirring the imagination.

The first movement begins with a somber funeral march that is grim and dour, in a rough-hewn key of C minor with apparitions of ghosts in the gentle references to the dies irae. Here Mahler seems to echo both Beethoven and Berlioz, but in a richer, multitextured counterpoint. The blend of the chant in the horns and the dotted figure in the strings was majestic and proud in the face of catastrophe. Leader Robert Waugh led the trumpet section through this classic excerpt with grave authority. In Mahler’s prescribed 5-minute pause after the first movement, the GCO wisely took the opportunity to (re)tune.

In his death, the hero remembers a life lived with its happy moments and others, perhaps less so. This is the topic of the second movement with its gentle ländler (a German folk dance) finding occasional pauses in sad nostalgia. Flautists Lisa Wolynec and Angela Reynolds deserve special mention for their delightful counterpoint to the string’s pizzicato second theme and Maestro Wolynec blended them quite well. It was warm and well done, however, it was in this movement that I missed Mahler’s huge orchestra—it reached for the pastoral but felt more a stylized version of the idea.

Principal Emily Crane and the rest of the strings brought out the next movement’s babbling brook with bubbling verve and a delightful col legno. An instrumental setting of Mahler’s lied Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt (St. Anthony of Padua’s Sermon to the Fish,”) the third movement was simply delightful creating a wonderful distraction that, as the orchestra ascended to the final frenzy—the famous “death schriek”—created a quite exhilarating effect.

The third and fourth movements, both essentially pastoral, contrast well with each other in tempo and style, but together they stand in great contrast to the spirituality of the fourth movement. The movement is an essay on the Romantic philosopher/wanderer, the Pietistic struggle for personal salvation written in the beauty of a single rose, it is one of Mahler’s most intimate and beautiful moments. Mezzo Teresa Buchholz sang with a mesmerizing timbre balanced brilliantly by the brass chorale from behind and below. Excerpt:

| O Röschen roth! Der Mensch liegt in größter Noth! Der Mensch liegt in größter Pein! Je lieber möcht’ ich in Himmel sein! |

O little red rose! Man lies in greatest need! Man lies in greatest suffering! How much rather would I be in Heaven! |

In the fifth and final movement, Mahler presents a grand and grandiose sonata form with a recapitulation realized, indeed made incarnate by the chorus. Further, the entire movement itself is a recapitulation or even a dénouement of ideas presented in the first movement—particularly the dies irae. Soprano Penelope Shumate sang beautifully, she was the hero to Buchholz’s philosopher. Douglas Rose’s chorus, immaculately prepared for yet another mammoth work this season, brought the symphony to its heights with not only a fantastic intonation, but a responsive dynamic that left the room breathless. It seems that the GCO is done for the season with this concert, but there is an event, tantalizingly titled ‘BBQ, Brews and Beethoven’ on the website. The three Bs? I’m down!

New in the Music City:

Blueprint & Jacob Jezioro at the Axiom Art Gallery

Nobody would blame you for missing the Axiom Art Gallery. Tucked away between Third Man Records and the Plaza art supplies store, the only signage in front of the building reads “Resident Parking Only.” It’s just as well, because the space in front of the vintage building that houses the Axiom Art Gallery leaves only enough room for a handful of cars. Fortunately, even on a Saturday night, this little elbow-shaped stretch of Seventh Avenue is quiet, either forgotten or yet-to-be-discovered compared to the hustle and bustle of the Gulch just a block or two to the West. So, you might have to hike a little, but parking’s no problem. The building has a wraparound porch and a number of large wooden doors, most of which apparently lead to private apartments. Tonight however, there were no issues figuring out which of the doors housed the art gallery. The swish of brushes on a snare drum and the probing sounds of a soloing tenor sax wafted out faintly from the front right door—exactly the sort of welcome you’d hope to get from a low-key event like this.

An event so low-key, in fact, I’m not even positive what to call it. The concert had a neat hand-painted poster floating around Twitter that featured a few ghostly-looking cats and dogs, one of the cats smiling pleasantly, the other with evil eyes and its claws poised threateningly. “Music to Ease Our [revolutionary] Minds” the poster reads with nothing else but a time and place. I never figured out if this was supposed to be the title or the subtitle of the evening, but I guess that ambiguity is the point. The words on the poster aren’t so much a title—a what this concert is supposed to be—but rather a description—a why make this music in the first place. And while I can’t say I ever pieced together the explicit political meaning of “Music to Ease Our [revolutionary] Minds,” I think getting caught up there misses the point. To give the performance a title and an explicit program would fix it in place and time. It would turn the living, breathing organism of structured, simultaneous improvisation into a fossilized museum piece completely out of the spirit of the whole affair. In other words, we have to understand music here not as a noun but as a verb. At one point in the night, right at the start of the second set, there was a bit of confusion as to which piece should go next. Performers and lead sheets were shuffled around the room as Jacob Jezioro, the force behind organizing the whole thing and the composer of a number of the works performed, conferred back and forth with his band. Finally, when things settled into place, Jezioro cried out “That’s jazz! That’s jazz everybody!”

You see that same spirit of improvisation in the putting-together of the whole concert too. Though Jezioro was the center of the evening, he shares the billing with Nashville’s Blueprint Ensemble, a relatively new ensemble looking to “[map] out the future of Art Music.” Blueprint was initially supposed to have a concert towards the beginning of March, which was unfortunately postponed. Jezioro, who was slated to play bass for Blueprint at this postponed show, suggested reworking a planned concert of his own into a collaboration—the setlist was reworked, some more members of the Blueprint Ensemble worked in, and the night was born. The performing lineup changed even more between the rebranding of the concert as a collaboration between Jezioro and the Blueprint Ensemble and the first downbeat. Chester Thompson, the legendary drummer, was apparently brought on to replace another drummer with barely a moment to spare. Sax player Joel Frahm, whose solos that night were unbelievable in their ability to thread the needle between scalar flourishes and almost-hummable tunefulness, glanced through a number of scores moments before the first set, occasionally asking Jezioro for clarification on a time signature here or an accidental there. And yet, you’d have no way of knowing. All of these musicians are Old Pros, putting together an entire evening of capital-G Great music in a way that’s hard enough to do with months of planning and the prospect of a big profit.

The Axiom Art Gallery might have housed twenty people that night all told, including the rotating group of performers, and there wasn’t much room for more. It’s a deliberately intimate space, perfectly suited to the spirit of Jezioro and the Blueprint Ensemble’s program. Most of the crowd knew each other and/or the performers, so even while you spent most of the night silent, breathlessly following another round of traded fours, there was a lovely social dimension to the proceedings. There’s nothing impersonal here. You’re making frequent eye contact with everyone, but especially the performers in a way that places you directly in the middle of the whole process. There’s no illusion that you are somehow on the outside, spectating neutrally. You get that sense that if you changed even a single thing about the setting, if even one person had decided to stay home that night, the fragile magic of the room would dissipate. Of course, it’s probably untrue, but if the Blueprint Ensemble are looking to program concerts in this space in the future, there’s certainly an opportunity to find or commission works that incorporate the audience more literally.

I think the boundary between performer and audience might be the final frontier. I said that I think we’re to understand music as a verb rather than a noun in this setting, and I think Jezioro’s program mostly achieves this. There was a dynamism to almost every aspect of this concert. Even its beginning feels less like a boundary than a suggestion, more an almost-overlookable change of atmosphere than anything else. Jezioro gave a few words of welcome and thanks to the in-person audience, but after he returned to his seat in the crowd, you would be forgiven for mistaking the beginning of Thompson’s improvised drum solo as him just testing his hi-hat. His first few hits feel almost non-metric, and the repetition of the same figure on the bass drum a few seconds later almost assures you he’s just warming up, that the real show is just about to start. And yet, just as soon as you’ve had a second to make sense of what you’ve heard, he’s moved on, now establishing more of a fixed groove, and it’s clear he’s soloing. The rest of the ensemble slowly peel off from the audience, one by one joining in. This improv gives way, again practically imperceptibly, to the first work on the setlist, a piece by Jezioro entitled Agape. It’s clear by the time David Williford is playing the tune on the clarinet that we’ve arrived at a Composition, a Text that can be said to exist in some form independently of its performance, and yet this gradual almost non-start refuses to give us that kind of certainty. It doesn’t so much reject the idea of the Text as remind us that what we call the Text isn’t something so much as it is a byproduct of performance itself, something we destroy in our attempts to contain it. Art, in other words, is something alive, and most concerts are more like a public execution.

I think there is one more dimension to the Text-ness of a work. It isn’t just a fuzziness between where one work starts and the other stops, or even the distance between the start of a work and the infinitesimal slice of silence that precedes it. Instead, like I’ve already mentioned, it’s where what’s being performed intersects with the audience there to hear it. The dynamic nature of jazz improv itself already interferes with this distinction. As anyone with even a shred of experience playing in a rhythm section knows, there’s as much moment-to-moment complexity in comping underneath a solo as there is to soloing itself. The process is necessarily interactive as jazz musicians play off one another both consciously and unconsciously in an almost intersubjective feedback loop where listening is playing and playing is listening. Therefore, to play a solo or to accompany a solo is to be both performer and audience member simultaneously, and yet, obviously, this same intersubjectivity can never really be shared by the audience. Axiom Art Gallery can make you feel like you’re sharing in it, but it’s always just right on the cusp.

Never was this tension clearer than in the performance of the only not-explicitly-jazz work of the evening: Rodney Lister’s Sestina. The piece is aleatoric and consists of dozens of pre-written sets of pitches arranged into “measures.” An ensemble of performers is free to realize these pitches at whatever rhythm feels appropriate in the moment, so long as each performer moves from “measure” to “measure” at the same time. What you end up with in performance is an interesting obversion of the usual dynamics of jazz improv, where a common pulse and the architecture of the changes unify the proceedings. Instead, here the performers are all playing the same thing (or more or less the same thing) but irrespective of pulse or harmonization. It doesn’t come across so much as heterophony as a kind of controlled, deliberate cacophony. The performers can’t listen to each other, or at least ought not to, because the only possibility of synchronization is a kind of monophony the random nature of the piece seems intent on subverting. The audience, however, must listen. You have no other choice. If any meaning, if anything Text-like, is to be found here, it must be sussed out, must be invented by the listener in real time. We’re left here with a compelling, largely unresolvable paradox. Much of the spiritual/philosophical motivation for aleatoric music (especially that of John Cage’s) was the eradication, or at least a radical de-centering, of the “authority” of the author over the text. It’s an early expression of what we’d now call post-structuralism, a term that’s only ever loosely defined, and more often than not applied to an artist, work, or school of thought rather than claimed by one. In any case, the tenets of post-structuralism have found far more purchase in writings about music (including my own) than in music itself. And here it’s not hard to see why. Aleatory may make delineating between Author and Text more challenging, but if anything seems to draw the distinction between performer and audience into sharp relief.

I suppose this is why I found the way the gallery was arranged for the concert to be so striking. The art in the gallery still hung on the walls, but we in the audience sat with our backs to it, the ensemble playing directly at it. Why is this, I wonder? Maybe it has to do with purely technical considerations. The event was, after all, livestreamed on YouTube (and remains available at this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZTfCBRKhy8U), so there could have been any number of IT reasons the ensemble was on one side of the gallery and the chairs for the audience the other. But even if unintentional, I’m left wondering if the arrangement worked to keep the audience from looking at the fixed works on the wall, or if the design forced the performers to fixate on them, in some sense perform for them, in a way that confuses this whole matter for me even more.

Live in Franklin:

LAGQ Concert at Franklin Theatre

The Los Angeles Guitar Quartet brought a warmth to Franklin Theatre on an April night of near freezing temperatures at show time. The intimacy in which the four guitarists blend their sound suited the small crowd. One patron informed me that LAGQ had been booked for dates nearly two years ago but was postponed until events could resume without pandemic restrictions. Now the quartet begins a three-show stint at Franklin Theatre before heading to Oak Ridge, TN.

We were a special crowd due to the fact that LAGQ released their album Opalescent that day and were happy to feature some of the works from the record. This would be their first live performance in quite some time in a year in which they celebrate 40 years as a quartet.

After opening with an excellent arrangement of “Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2”, member Bill Kanengiser introduced the piece “Opals” by Phillip Houghton and explained how the music depicts “the glints and reflections of the gemstones.” Houghton was a synesthete meaning he saw specific colors when he heard musical tones. Kanengiser explained that in the score he writes certain colors that are represented above some notes.

“Chorale” by Frederic Hand was performed with the utmost attention to ensemble interplay with the purpose of turning four guitars into an acapella vocal ensemble. As all four musicians took cues from their scores on music stands, I could not help but think that they were putting more into the music than just reading from the page. There was very little physicality happening on stage but the sound had this wonderfully dense, warm harmonic movement that swept you along.

John Dearman introduced two movements from Road to the Sun (2021), a project composed by Jazz legend Pat Metheny for LAGQ. Metheny’s themes weave in and out of colorful harmonies and the four guitarists are constantly trading melody, strummed chords, and other parts of the music. This lengthy performance that pulled us into the musical world of a brilliant composer and defied genre took us into an intermission.

Returning from the break, Matt Grief spoke about a past project called Guitar Heroes (2004) that featured the group’s arrangements of some of their favorites. These tunes included an infectiously groovy “Peaches en Regalia” by Frank Zappa and an elegant medley of “Blue Ocean Echo” and “Country Gentleman” by Chet Atkins with a coda of “Wind Cries Mary” by Jimi Hendrix seamlessly added on. Matt Grief subtly slipped a glass slide on his left hand to add something special to the Chet Atkins songs and completely fooled us that he was still playing a classical guitar!

The audience cameras went up during the second movement of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” which Scott Tennant introduced as a special arrangement done by Bill Kanengiser after an invitation to the Beethoven Fest. It was captivating and especially effective for guitar, making good use of the bass notes on John Dearman’s 7-string guitar.

The finale was an explosion of notes from composer Manuel de Falla’s El Amor Brujo. The two movements “Canción del fuego fatuo” and “Danza ritual del fuego” satisfied the crave for Spanish guitar music and exhibited some of the polished musicianship that comes with 40 years experience performing as a group.

The LAGQ have been inducted into the Guitar Foundation of America’s hall of fame and received the honor from Pepe Romero of the famed quartet The Romeros in a special 2021 ceremony. In a conversation with Bill Kanengiser one week before this show, he told me they have enjoyed the journey and he addressed the future of the guitar ensemble by saying the guitar quartet is here to stay. We are thankful to have hosted them here in middle Tennessee and I believe LAGQ will continue to bring these high level performances to audiences across the country for many more years.

From Nashville Opera

Rigoletto Noir…Finally!

Over the weekend, Nashville Opera finally managed to pull off their long-awaited Rigoletto Noir, complete with a three-minute, film-noir-inspired cinematic short created by Nashville natives Chris Hollo and Mark Mosrie of Penumbra Entertainment. While I wouldn’t go so far as to say it was worth the wait (nothing is worth the pandemic) the

evening seemed like a wonderful return to the way things used to be. When it comes to Italian opera, Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto is a chestnut and has been one since its triumphant 1851 premiere in Venice, and this is despite its dark subject matter—Venetian Police Censors attributed a “‘disgusting immorality and obscene triviality” to Piave’s tragic libretto. Remarkably, this makes for an excellent noir narrative, a film genre characterized by cynicism and tragedy, and thankfully, Director Hoomes managed to avoid the trap of genre parody.

Onstage and fresh from his appearance as Shchelkalov in Boris Godunov at the Met, Ukrainian baritone Aleksey Bogdanov played an outstanding Rigoletto. With a dark instrument, awash in luster and bluster, and a charming presence in the Duke’s court, Bogdanov’s Rigoletto quickly becomes as threatening and self-centered as Leoncavallo’s Canino (shame in clown makeup and all) by the banks of the Cumberland (this staging is set in the Music City). Indeed, the brilliant staging has more than a little commedia dell’arte to it. Rigoletto’s jester’s smock, a part of his costume of shame, is patterned in blood red harlequin diamonds.

As Gilda, Soprano Sarah Coburn was beautiful, gentle, and delicate but with a full, bright instrument. Her “Caro nome” was the ideal. The fulcrum of Verdi’s tragedy, her character has a direct and predictable arc, which is central to the staging’s subtly diagetic, and yet ignored, expressions. As the Duke, tenor Daniel Montenegro seemed to have an off night (Thursday). His intonation and color were quite good in solo pieces, but just a bit weak in volume. It must be said that this role is a terrifying challenge given how often it has been sung by the great tenors—Pavarotti, Domingo, Carreras etc… The challenges created by this were well handled in the adaptive balance maintained by Maestro Williamson and Nashville Opera Orchestra. Unfortunately, Montenegro was often all but drowned out in the ensembles, especially the famous quartet in the grand finale.

Dean Williamson led the Nashville Opera Orchestra quite well, with nuance and a sense of forward motion. The opening scene complex with its sections of contrasting yet continuous music was quite fun and the chilling moments (the brassy curse idea in the overture, the sinister strings and woodwinds in Rigoletto’s duet with Sparafucile) were scarier than I think I have ever heard them.

The Courtiers were very well prepared by Amy Tate Williams, participating in the great fun of precipitating a tragedy. Their aural appearance as the wind in the great finale was absolutely chilling. Mezzo Emily Triebold was seductive and darling as Giovanni, and Kevin Thompson brought a pragmatic business sense and a huge bass voice to the role of the assassin Sparafucile. The costuming (June Kingsbury) Wigs & Makeup (Sondra Notttingham) and Lighting/Video Design (Barry Steele) deserve special mention for their huge contribution to this spot-on production. The biggest drawback, and probably what might fairly be considered Nashville Opera’s curse all these years is the hall. Andrew Jackson Hall at TPAC is just horrible for opera—too big and the sound and nuance gets lost in all that space. One waits in anticipation for Nashville Opera’s May 6 and 8 production of Richard Wagner’s music drama Das Rheingold in Belmont’s fancy-pants new performance hall. Perhaps it will have better acoustics.