The MCR Interview:

MaryGrace Bender and the Nashville Chamber Music Society

Benjamin Gates had a chance to chat with the new star on the Music City Horizon, the Nashville Chamber Music Society’s founder and director, MaryGrace Bender. The following is a transcription of that interview:

MCR: On the Nashville Chamber Music Society’s website, you write that you held on to the ensemble’s web domain for years with the hope you could turn it into something. So what is the Nashville Chamber Music Society, and how did it finally end up going from a URL to a real thing?

MGB: So, the Nashville Chamber Music Society is a group of professional classical musicians in and around Nashville. I grew up in Nashville. I was in the Vanderbilt pre-college program, and growing up, I just really saw a need for chamber music concerts in Nashville. So I went off to school, and I bought the domain, probably like end of high school, I want to say, and I was like “Someday I’d love to make this a thing! I’d love to have chamber music in Nashville and be able to invite friends and just do this together, find ways that we can actually serve our community as well, whether that’s school concerts and even right now, I’m thinking through what could we really do to make a difference. How can we serve communities that aren’t getting to experience beauty in this way? So, I actually started during COVID. I was working at Frothy Monkey as a barista and a server, because, of course, the music world and everything shut down and I needed to pay rent (laughs). So I was working there, which I really enjoyed actually, and I had so many really excellent classical musician friends that didn’t have a place to play. So it started off, I just talked to my manager and I was like “Any chance we could do socially-distanced tables?” because Wednesday nights, Frothy Monkey does this Wind Down Wednesday and I was like “Would it be okay if me and some of my friends just like played some like Beethoven quartets for the people that come on Wednesday nights?” and she was like “Sure!” So I booked kind of this six-week series, and people had to buy tickets in advance, well, it was actually free, you just had to reserve your spot in advance to reserve a table because you had to wear your mask and be socially distanced and all of that stuff. And after the first night, all of the rest of them were reserved for like six weeks. It was fully booked, and I was like “Wow! This is great! And I love that people are excited about this!” And of course, it was a blast getting to play with friends. So that’s how it started. It was very simple and fun. And as things with COVID started to change, I started looking around at different churches and venues and places that could host a concert. Tim Nicholson, who is the music director at Covenant Presbyterian Church in the Green Hills/Brentwood area, reached out, well, we got connected through a friend, and he was like “Oh we’d love to have concerts at our church if you guys want to be kind of the resident ensemble here.” And I was like “This is perfect!” (laughs) I was so excited. So, we scheduled some concerts with them, and we’ve been just very slowly growing our audience and growing the network of chamber musicians within Nashville. I’ve definitely had some groups coming in from out of Nashville, when I get to a place where I’m like “Everyone’s booked, and I really need a violinist!” So I’ll call one of my friends from school or something to fly in, so every concert is kind of a different crew, but, yeah, it’s been very, very fun. But kind of the idea is that each concert has like a school concert, an outreach concert, and a venue concert, and so I’m trying to stay really faithful to that to make sure that we’re reaching different kinds of audiences.

MCR: Besides founding and running NCMS, you’re also an active Suzuki teacher and spend your time, as you describe, “passionately promot[ing] the arts at a grassroots level.” For those who may not know, could you explain the Suzuki method briefly, maybe how you came to it, but more importantly how it and your musical outreach tie into your work at NCMS?

MGB: So I grew up in the Suzuki method. The Suzuki method is a way of learning music just like we learn human language, well English or whatever language you learn. We learn our native language by being immersed in it, by hearing it and learning by repetition and copying. That’s kind of how the Suzuki method works—kids learn by copying and listening and creating a sound in their head of what they want and what they can repeat back, and they learn to read music just a little bit later, just in the same way we learn to read normally around preschool/Kindergarten, but we’re already speaking at that point. So, I try to get the kids to be “speaking” the language of music before they start reading the language of music. And so I grew up in the Suzuki method at Vanderbilt pre-college, again, and then went on to school and to conservatory and got my Masters in Suzuki pedagogy, so I got registered in Suzuki method, and I knew that I would love to teach music at some point, because obviously music has had an incredible impact on my life. My first teacher, Anne Williams, who is now retired, but was a cellist in Nashville, really gave me the gift of music in an incredible way, so I just always have admired her and wanted to be like her. So, I teach. I have about 17 students. I actually live in Huntsville, Alabama now; I just got married and moved over the summer, so I drive into Nashville for NCMS and for teaching one day a week. So I teach my kids in a long, full day! (laughs) And my ages span from a 4 year old up through like end of high school, like kids getting ready to audition for colleges. So that kind of connects through, like a lot of my students play in retirement homes and I have them do outreach concerts along with their regular recitals because if music isn’t given to other people, it’s a joy to practice on your own, but it has to be given to other people to fully experience music. So I try to encourage that with my students and try to promote that any way I can with NCMS as well.

MCR: As you well know, the NCMS’s spring season kicks off next week with a program called “A Walk Through Italy,” which appears to have a special focus on repertoire featuring the guitar. Can you talk a bit about the pieces on the program, and a little of what you hope or expect the audience to take away from it?

MCB: This concert came about because Miles McConnell, who is a local classical guitarist, reached out to me about a year ago, and he really presented me with this program, he was like “Hey, would you be interested in doing this program? I have some of this music ready.” And I was like “Sure!” So we looked through, and it was a great program. It’s all Italian-based music. It’s very warm and welcoming and inviting to any audience member who has little to no experience with classical music or knows a lot about classical music. It’s just a very welcoming program. Yes, it’s very guitar-focused, and I think each of the pieces is quite challenging and fun for the quartet as well. We get to add a lot to the guitar, and the guitar adds so much color to the quartet. Probably one of my favorite ones on the program is the Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco Quintet for Guitar and Strings. It’s just so creative and the first violin, who will be Jimin Lim, who’s in the Nashville Symphony, she just gets so many melodies and it’s just really beautiful. Also, I’m excited to kind of walk through each of these pieces. I think it will be a really colorful and beautiful journey for the audience members.

MCR: So to wrap things up, of course next week’s concert is only the beginning of the spring season for NCMS. What else should concertgoers look forward to from you all this season?

MCB: Yeah, next in our season we have Annie Fullard and Friends, which will be really fun. I’m in a quartet here in Nashville called the Zimri Quartet, and all four quartet members have studied with Annie Fullard at one time. She used to be the Director of Chamber Music at Cleveland Institute of Music, and she’s taught at my undergrad, which was the McDuffie Center for Strings. And she’s just been a huge influence to all four members of the quartet, so we love her dearly. And so we called her up and I was like “Hey! Would you want to come do a concert with us?” And she was like “I would love to!” So she’s coming down. It’s a double viola quintet, so that’ll be a lot of fun. And then the next thing we have is the Ivalis Quartet, which is another group of friends that I’m excited to have come down. They’re in residence at the Juilliard School and have made just an incredible impact in the music world and music education, and I love them dearly and am so excited to have them come. We don’t know their program yet. They’re going to let us know as soon as they can, but they’re putting together, I’m sure, something really special. And then the last thing this spring, and there’ll be a couple more this summer, but the last thing this spring is featuring a local composer, Noah Fran, another person that reached out to me and he was like “Hey, I wrote this piece, and I would love to get it performed.” So we both studied through the score together and I was like “This is going to be really fun!” So I would love to do more of that, like featuring local musicians and local composers and letting an audience hear what they’re creating. So that’s what’s to come this spring.

MCR: Awesome. That’s great! Thank you so much.

MCB: Yeah, absolutely!

Theatre Nohgaku at the Frist

It was a misty gray afternoon, not cold, but comforting, a stay-inside kind of day, the kind of day you commonly see in the Japanese countryside, the kind of day you commonly see from the windows of the lightning-fast shinkansen train headed from Tokyo to Kyoto. It was the kind of day when you hope the mist will clear away just long enough to see the celestial peaks of Mt. Fuji in the distance.

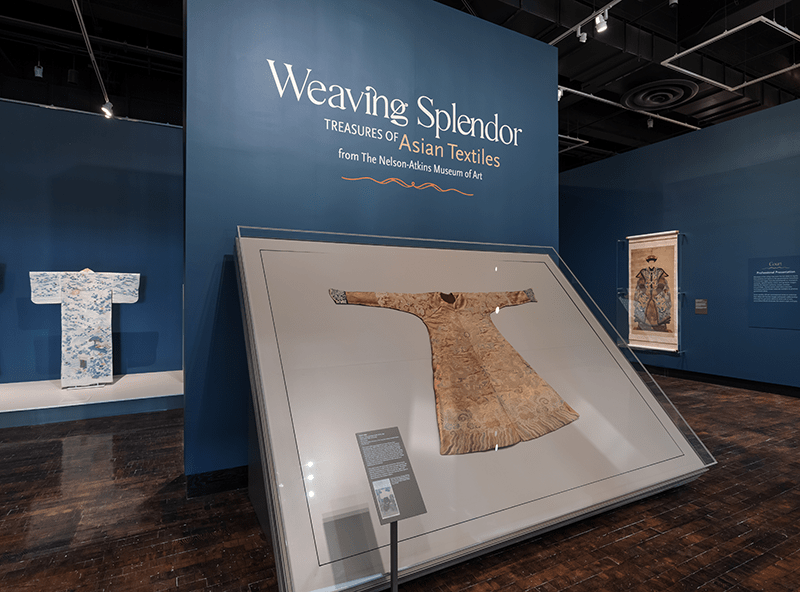

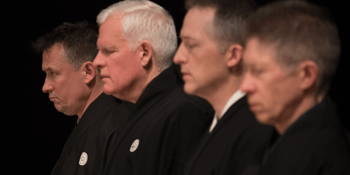

Nashville’s Frist Museum, quiet on Sunday afternoon December 4, 2022, provided the perfect setting for one of the oldest, most serene, continuing art forms in the history of theater. Theatre Nohgaku, an international ensemble, honorably preserves this masked art form, Japanese Nōh drama, whose words, movements, music, costumes, and dance represent 600 years of history.

As a complement to “Weaving Splendor: Treasures of Asian Textiles from The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art,”, an exhibit on Asian weaving techniques, the Interpretation Division, directed by Meagan Rust, hosted Theatre Nohgaku’s concise lecture demonstration on Nōh techniques. Because of the skeleton crew of only three performers for excerpts that would normally require at least a dozen, the performance was just a barebones synopsis. Despite these incomplete aspects and a few stylistic issues, the performance was remarkably effective and well-received by the diverse audience. Members of the ensemble presented excerpts from four famed Nōh plays, each preceded by a demonstration of specific aspects of Nōh performance, including techniques for singing, movement, and instruments.

(Those unfamiliar with Nōh drama may want to read my primer)

Story synopsis:

The spirit of Lady Izutsu, comes to a traveling monk in a dream. In this excerpt, she still seeks her unfaithful husband in the afterlife, dressing in his cap and robes while dancing as she once did.

The “Jewel Song [Tama no dan]” from Ama, is a tragic tale of a working-class mother who sacrifices her life in order to gain social status for her son.

Sumidagawa displays a mother who has finally located her kidnapped child, only to find he has died. This realization, coming from the boatman as they cross the Sumidagawa River, leads to her sobbing at her son’s gravesite.

In Hagoromo, a fisherman chances upon a gorgeous feather robe hung on the branches of a pine tree. He agrees to return it to the spirit who needs it to return to the heavens, if she will dance for him.

David Crandall, a founding member, introduced the vocal techniques of kotoba and yowagin. Used for dialogue or monologue kotoba consists of deep-pitched chanting with wide, slow vibrato. Yowagin, more melodic, stays mostly in the midrange with long tones topped off by lighter, tighter vibrato. Crandall, a Michigan native with degrees in Japanese literature and music, sang a kotoba style excerpt from Itsuzu in Japanese and denonstrated yowagin in English for “The Jewel Song” from Ama. Both styles were clearly evident in the English rendition of dialogue and arias from Sumidagawa.

Even in English, the excellence of the kotoba chanting style of vocal timbre and vibrato was an unexpected success. Crandall’s training in literary translation and deep understanding of traditional Nōh vocal performance based on more than twenty years study resulted in wonderfully effective adaptations of the texts. In fact, his technique was so authentic, I could close my eyes, imagining myself back in Tokyo.

Jubilith Moore demonstrated the suriashi, the standard slow gliding steps of Nōh, along with other movements like shiori, moving one or both hands down in front of the mask to represent falling tears. She and Crandall also explained the complex construction of masks made to last for generations.

Musicologist David Salfen, Professor of Music at University of the Incarnate Word in San Antonio introduced three of the four standard instruments for the hayashi ensemble that accompanies Nōh singing and dance, but also provides palette cleansers like “Chu-no-mai.” Salfen played the Nōhkan, a high-pitched wooden transverse flute which, uniquely, is a melodic instrument serving a rhythmic function. Moore played one of the two hourglass-shaped tsuzumi drums, each carved from a single piece of wood. Both have heads of horsehide on each end bound with heavy hemp cords.

Like the tama talking drums of West Africa, Moore’s ko-tsuzumi shoulder drum has pitch changes caused by squeezing and releasing the cords as the head is struck by the right hand. Crandall’s larger o-tsuzumi hip drum is designated as “male” but is higher-pitched because it is struck by hardened papier mâché thimbles. The fourth drum, struck with sturdy dowels only appeared in the final number, the iconic “Feather Robe Dance” from Hagoromo. One missing aspect of the instrumental explanation was the amazing kakegoe. These loud drum calls, signaling section breaks and tempo changes, continue throughout the performance regardless of whether singing or dancing are present.

This unusual trait was later addressed during the brief Q/A after the performance, but for those new to Nōh, an earlier mention would have served well. Another aspect diverging from my past Nōh experience is the sense that the performance was too fast, that the company had adapted the tempo for American audiences. This was a disappointment because exhibiting tremendous control through glacial slowness is one of Nōh’s most unique characteristics. The highly stylized gestures typically used by the hayashi instrumentalists for each drum stroke or removal of the flute from the lips also seemed a bit in absentia.

Overall, however, the final Hagoromo excerpt, the dance a heavenly spirit offers to a lowly fisherman in exchange for the return of her feather robe, combined all the main elements the audience had viewed so far: vocal techniques, dance, instruments, bringing a fascinating program to satisfying completion. Theatre Nohgaku was a welcome peak in Nashville’s artistic landscape on this cloudy day, a glimpse of Mt. Fuji.

From the Nashville Symphony:

Lisiecki and Melodic Bounty at the Schermerhorn

At the Nashville Symphony this past weekend, the audience was treated to a melodic bounty. Frédéric Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 1 and Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances made a curious program. A duality emerges with the pieces: Chopin wrote his concerto when he was barely 20 and the Symphonic Dances was the last piece Rachmaninoff wrote at the age of 66.

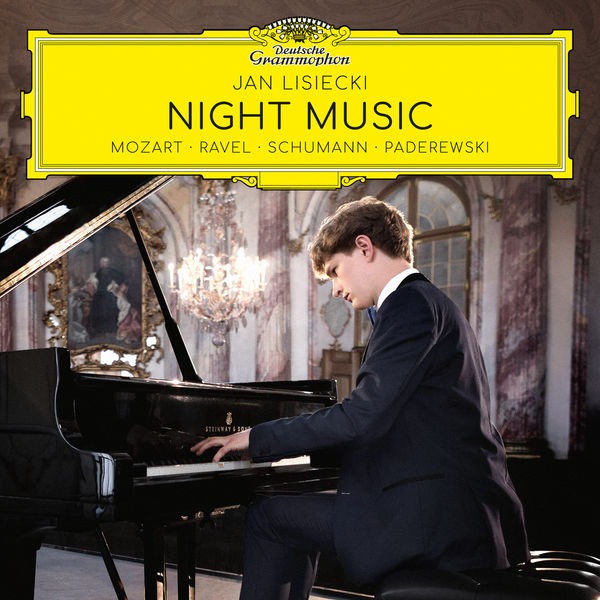

The overwhelming highlight of the evening was Jan Lisiecki’s performance in the Piano Concerto. Lisiecki, only 27, is just at the beginning of a career that makes one wonder, truly, how high is the limit? He has performed in subscription series events with the likes of the New York Philharmonic, the Vienna Symphony, and the Boston Symphony. At the age of 15 he signed an exclusive record deal with Deutsche Grammophon and has since recorded nine albums with them, three of which are dedicated to Chopin’s works, including his complete Nocturnes, some Etudes, and his Piano Concertos. One of Lisiecki’s chief interests and accomplishments is with the work of Chopin. When he was 13 years old Lisiecki gained international attention for his performance of Chopin’s 2nd Piano Concerto at the “Chopin and his Europe” event in Warsaw, Poland. In my preview interview with Jan he mentioned that “there are certain composers which have a particular importance with which I have an affinity, a rapport. Chopin is certainly one of those. When I sit down at one of his compositions, I feel as if I understand the language. I know what I would like to say and I know what he is saying to me through the music.”

As such, Lisiecki has gained a reputation as one of the foremost interpreters of Chopin today and that talent was on full display Friday night. The first movement “Allegro maestoso” had all the gravitas required. At the beginning of the piece, the orchestra introduces every main theme before the piano enters. When Lisiecki did enter it was clear that he was fully in command of this performance. The first movement accounts for about half of the length of the forty-minute piece, but at no point did it ever feel tiresome. The second movement, a slow Romanze, is a loose sonata structure. This movement is unabashedly melodic and romantic. I do not believe that I have heard a more sensitive performance of this piece. As a matter of fact, I do not think I have heard a better piano soloist at the Schermerhorn—ever. In a letter to his friend Tytus Woyciechowski, Chopin described this movement as “calm and melancholy, giving the impression of someone looking gently towards a spot that calls to mind a thousand happy memories. It is a kind of reverie in the moonlight on a beautiful spring evening.” This movement calls for the utmost delicacy. The orchestra takes much more of an accompanying role as the piano meanders up and down the keyboard. One highpoint of this concert was towards the end of this movement where the piano has three measures of transitionary material. Chopin uses simplicity, moving simple grace notes to basic chords, before beautiful cascading chromatic runs alternate with ascending arpeggios. During this small moment the audience held its collective breath as Lisiecki held the music in the palm of his hand. The third movement is a rousing Polish dance in rondo form, where the main theme is brought back again and again after contrasting themes interject. This concluding movement had the fireworks necessary to end a big concerto and the audience was waiting to reward Lisiecki with their applause.

After several curtain calls Lisiecki came back out to play an encore. After greeting the audience and wishing them a Happy New Year, he played Chopin’s Nocturne in C# minor. When he announced it from the piano I was surprised at the choice; this is a somber piece and not the traditional light fare for encores. It is not a terribly complex or showy piece and does not require the level of virtuosity that concertos do. But after hearing two measures I realized that this was not the same Nocturne that I was familiar with. This was the C# minor Nocturne with a new level of profundity that I had not known was possible. Here is a performance of Jan playing this Nocturne, however it really does not capture the sound that the Schermerhorn provides in a live experience. This encore was the climax of the concert for me.

Overall, the first half was incredible. To hear one of the foremost interpreters of Chopin playing one of his concertos live was well worth the price of admission. The piece itself is not my favorite. Chopin only wrote a handful of works with the orchestra, and it is clear he was never quite comfortable writing for the orchestra; it does not have the same lucidity that he achieves in his solo piano works. Yet this was certainly a showing of the piece in its best light.

At intermission I headed straight for the gift shop hoping to get a CD of Lisiecki’s, but the gift shop was closed, perhaps a relic of the Covid era. (Curiously, when you visit the Nashville Symphony’s online Shopify storefront you are greeted with a “Sorry, this shop is currently unavailable” banner as well). Heading back to my seat I wondered if anyone even bought CDs anymore.

One note to my fellow audience members. I believe that we should all be a bit braver, myself included, in hushing an audience member during a performance. There was a gentleman and his date about 6 rows in front of me whispering loudly. After the first minute or two of people turning heads and staring daggers everyone gave up and allowed them to talk through large sections of the performance. Certainly, the concert hall is a welcoming space, but it is also an area to set aside the worries of the world and be in the presence of some of the greatest pieces of music ever written. And that should be treated with the basic courtesy of allowing your neighbors to hear the pieces uninterrupted.

The second half of the concert was Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances. It is an “unofficial symphony.” It meets all the criteria of a symphony, but Rachmaninoff never gave it that distinction. Originally it was titled “Fantastic Dances” with the three movements titled as “Noon”, “Twilight”, and “Midnight.” Some have reflected that these movement titles do not refer to actual periods of the day, but periods in Rachmaninoff’s own life. This would have required tremendous foresight on Rachmaninoff’s part to predict his death a few years later. It is for the best that Rachmaninoff scrapped the titles for the movements.

The first movement is a good example of Rachmaninoff’s late style: gorgeous melodies, quick shifting harmonies, and a focus on sparer orchestral colors. This movement has an alto saxophone solo and is the only time that we know of Rachmaninoff writing for the instrument. The second movement is an addicting waltz and is strongest of the movements. The last movement features the “Dies irae” theme that is seemingly all over every Rachmaninoff work. This work expands on the darkness of the second movement, varying between faster and slower sections. The orchestra played solidly under Giancarlo Guerrero’s baton. There were a few trifles with intonation throughout, but with so much turnover in the orchestra in the recent years that can be forgiven. This was another solid showing for the Nashville Symphony and I am looking forward to hearing what they bring next.

The MCR Interview

Interview with Pianist Jan Lisiecki

On January 6-8 the Nashville Symphony will present a concert at the Schermerhorn Symphony Center that features Canadian pianist Jan Lisiecki, “one of the most astounding, in-demand young pianists in the world today,” performing Frédréich Chopin’s First Piano Concerto (Op. 11) and Sergei Rachmoninoff’s Symphonic Dances (Op. 45). On behalf of the Music City Review, contributor Daniel Krenz took the opportunity to ask him about a few questions about the pieces and his preparation for the performance. The following is a transcript of that conversation*:

Daniel Krenz (MCR): Good afternoon, it’s a pleasure to speak with you!

Jan Lisiecki (JL): Good afternoon, it is nice to talk to you today.

DK: Have you been to Nashville before?

JL: No, I have never been to Nashville, and this is my first time going to Tennessee. I am really looking forward to it. I have played with Giancarlo previously at his other orchestra in Wrocławska, Poland in March 2021 during the pandemic.

DK: Your first album was a recording of both of the Chopin piano concertos. The audiences in Nashville this weekend are going to be able to hear you in his First Piano Concerto. His work must mean a lot to you, what was your first experience with Chopin?

JL: As a performer you always find certain music speaks to you. In particular my personal favorite is classical music. If you look within classical music there are certain composers which have a particular importance with which I have an affinity, a rapport. Chopin is certainly one of those. When I sit down at one of his compositions, I feel as if I understand the language. I know what I would like to say and I know what he is saying to me through the music. That, I think, has existed since very early in my playing of the piano and it certainly continues until today. Of course, the way I play Chopin’s first piano concerto has changed drastically from when I recorded it when I was fourteen years old. Fourteen years ago was half a life time away! It is something that has been with me. I have played around the world in countless countries on many continents and I have grown in my understanding of the piece. Every performance shapes what I do with it. I love it. I am really looking forward to bringing it and sharing it with the audience in Nashville.

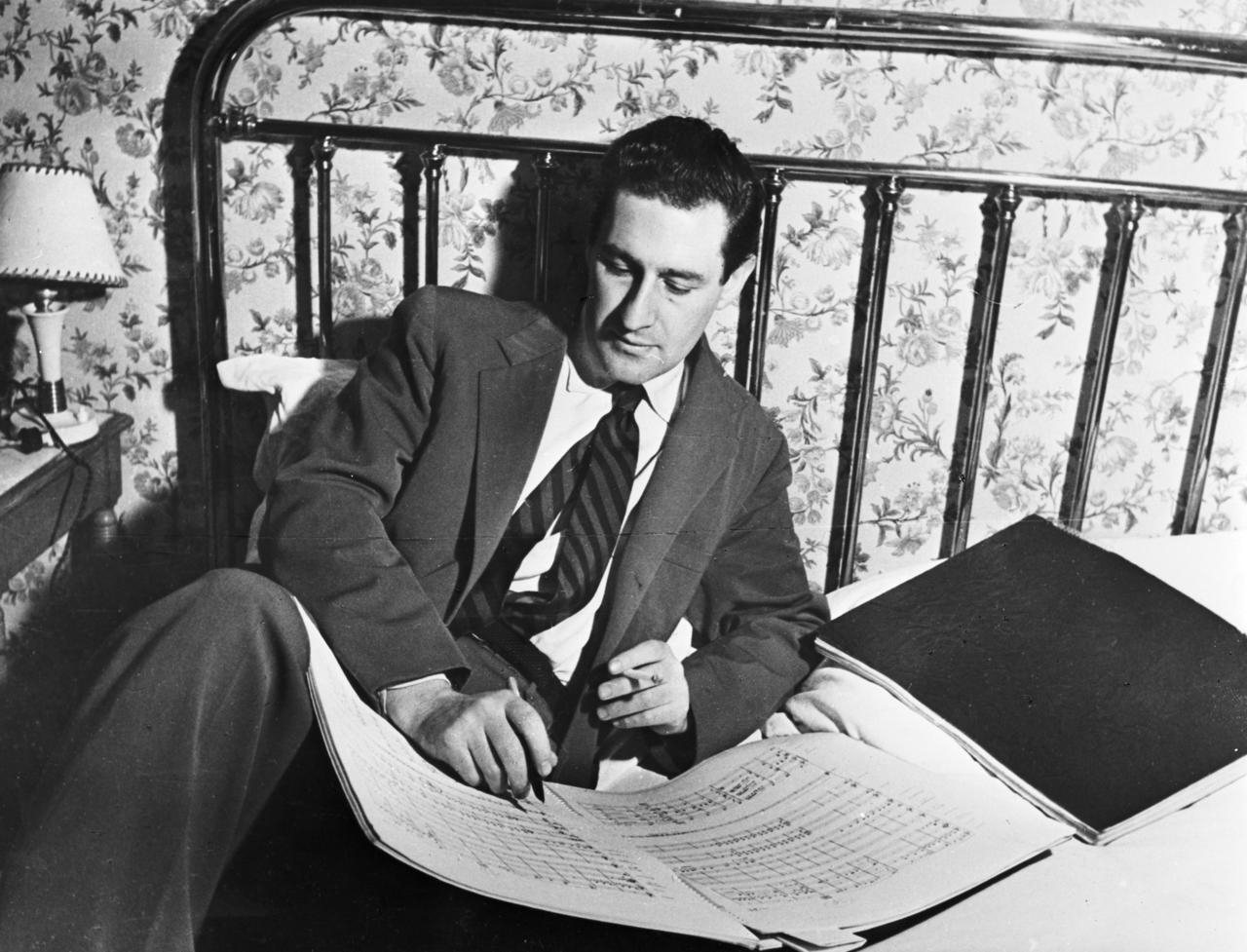

DK: As a touring soloist you are playing and preparing these pieces constantly. Is there anything you do in particular to help keep these pieces fresh?

JL: Certainly, there are some days you have to consciously sit down with the score in front of you and look it over again. And of course, you play all of this music from memory. But it is not only from memory, but it is internalized. When you internalize something, perhaps one would say, too much, you get to the point of playing your own version of it as opposed to what the composer actually wrote in the score. The only way to get back to basics, to the foundations, is to look at the score once again. So, you do that once and a while. Otherwise, the actual innate freshness comes from your own experiences. I will have a different experience each time I play the piece. The last time I played this piece was in Iceland in Reykjavík in November. Certainly playing it in Nashville now, with a very different orchestra, in a very different environment, different country, different climate, a different mood in the new year… You have different inspirations and you adjust to that. On stage you are creating. The biggest gift as an interpreter, as a performer, is that every day will be different. And of course you go based off of the energy on the stage with you and those that are in the audience. That interaction is very important.

DK: Chopin wrote very little works outside of just solo piano and the Piano Concertos are some of his best-known pieces with orchestra. They have been accused of having a weak instrumentation. As you mentioned, from time to time you will sit down with the score again to get back to the basics. What are your thoughts about how Chopin handles the interactions between the solo piano and the orchestra?

JL: The way I look at these concertos is as piano sonatas with orchestral accompaniment. That orchestral accompaniment is quintessential because Chopin had a very vivid imagination on how the orchestra should sound. Was it entirely accurate? Was he the most talented at brining that philosophy from the page to the concert hall? Perhaps not. But he was able to add more colors and emotions into the music by using the instruments in the orchestra. Of course, a piano has a particular sound, one that I like, but the way Chopin uses for instance the Bassoon and the French Horn to play solos is wonderful! It is unique. One has to be simply conscious of the fact that a solo Bassoon or solo Horn can not compete with a modern instrument and a modern string section which has a very big sound. But that is their responsibility on stage. One could say it isn’t as natural an orchestration as one of the greats of symphonic writing, but it certainly has a place. Working with an orchestra in all of my experiences with this piece, it is still a pleasure. And I think the musicians also find it a pleasure when they have a soloist that pays attention to what they are doing.

DK: Is there a particular moment or movement in the piece that is a particular favorite of yours? A moment that you would like to point out for the audience to pay particular attention to?

JL: Let me think, because there are quite a few! I would suggest for instance in the 3rd movement at the very beginning there is a drastic change from the serene and lush sound that we just heard in the 2nd movement. It is attacca, which means it is played without a break. After that introduction, we have a moment where the whole cello section is playing pizzicato. Listen to the way they lead from the dramatic entrance into the dance of the 3rd movement. It is called Krakowiak, a Polish dance. They have a little bit of a ritardando and I think that is a really fun moment to listen to. And it only happens once in the whole piece. If you miss it you won’t be able to hear it again!

DK: Thank you for time and I am looking forward to the concert.

JL: My pleasure, thank you!

The Nashville Symphony plays Chopin’s First Piano Concerto, with Jan Lisiecki, and Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances this weekend January 6th, 7th, and 8th.

*This conversation has been slightly edited for clarity.

At Analog at the Hutton

“This Is Just A Story”: Chatterbird and Insomnia’s My Closest Friend

“This is just a story. You’ll understand it if you listen,” says Tavius Marshall in the new work Insomnia’s My Closest Friend with text by Marshall and music by Joshua Dent. The work premiered at Analog at the Hutton in Nashville this past Monday, performed by the Chatterbird ensemble. In the piece, Marshall’s spoken word poetry charts a course through his own life and the ongoing struggle to find a balance between being a “Manic Maniac and Black, Biracial, Bisexual, Depressed artist.” Marshall’s clever wordplay and passionate emotional intensity are accompanied by Dent’s intricate string and percussion writing, which tends to break into a blistering, lovely lyricality during the instrumental interludes between the major spoken word movements. The work contextualizes Marshall’s often-turbulent biography in light of the history of mental health, socially acceptable modes of creativity, and the way social stigmas surrounding mental illness are compounded when someone navigating these issues presents as black and/or biracial.

Though Insomnia’s My Closest Friend is a work with a number of complex themes, one of the richer and more striking is the way that Marshall frames the relationship between mental illness and his own creativity. Obviously, in that this piece is about Marshall’s mental health struggles literally, there’s an irreducible degree to which the piece will have to frame those struggles as a “source” of that creativity, both in the case of Marshall’s poetry and Dent’s accompaniment. Take for example the expressive character of the second movement “Mania.” As the movement reaches its peak of intensity, the intricate, rhythmic layers of Dent’s ensemble writing very nearly drown out the delivery of Marshall’s text, right as that text’s sense of semantic coherence reaches a point of almost-dreamlike, free-associative incomprehensibility in its own right. In other words, both text and music here and throughout the structure of the whole work treat Marshall’s “Mania,” “Depression,” and cry for “Help” as the subjects of a series of continuous character portraits.

And yet, at every moment Marshall pushes against this sort of simplistic 1:1 reading. “My stint as an artist,” Marshall says in the last movement, “offers me to take my crazy the farthest, creating an outlet so I don’t need to starve this part of me,” and yet it’s clear throughout the work, as he describes the difficulties of holding down a job when you can’t sleep sometimes for four or five days at a time that there’s absolutely nothing romantic about bipolar disorder. And “Romantic” really is the keyword here.

In ways that are often hard to parse, the cultural inheritance of the 19th century informs many of our basic notions of art and artistic creativity, and perhaps nowhere more prominently than in the world of music. It seems hardly surprising given that Romantic ideas about the power of the irrational and sublime seem almost perfectly suited to the wordlessness and textural potentiality of music. It’s then equally unsurprising that “musical genius” and “madness” were practically synonyms by the end of the 19th century and remain so vestigially in the all-too-frequent depictions of Beethoven the “tortured” genius or an over-emphasis on the effect of mental illness on the music of Robert Schumann.

Historian James Whitehead’s Madness and the Romantic Poet: A Cultural History works through the historical construction of a connection between “madness” and artistic “genius,” which he argues reached its zenith in the heights of the 19th century. Whitehead demonstrates that Romanticism was not so much a cultural “response” to the rationality and orderliness of the preceding century and the Enlightenment as so many others have argued, but rather, perhaps counter-intuitively, an extension of it into the rapidly changing sociopolitical scene of the early Industrial Revolution. The “mad genius” was not an avatar of revolt against 18th century order, but rather a post-facto cultural means of containment for the irrationality that persisted into the age of industrial capitalism, colonialism, and the rapid technological change that supported both. In this account, Whitehead draws largely on Michel Foucault’s History of Madness, which frames “madness” not so much as a useful term describing a given set of medical symptoms, but rather as a culturally constructed category that can readily and effectively cordon off any socially or politically disagreeable ways of thinking or being.

Marshall too draws on a similar line of thinking in the first movement, where he describes the term “drapetomania,” coined in 1851 by the American physician Samuel A. Cartwright to explain away as mental illness the fact that so many enslaved people attempted to flee captivity. Or in Marshall’s own words “Insanity used to be the pathological intent to escape from slavery!?!” The same idea runs throughout the rest of the work. Marshall’s “circular calamity of collapsing mental galaxies” and the insomnia, alcoholism, and inability to focus he describes stemming from it create problems that compound themselves in light of the necessity of paying bills and of facing a world built for white men on the backs of black labor. Or again in Marshall’s own words

Under the plea for normalcy being black or being free becomes “lunacy” and the machine was never updated, just repurposed not desegregated we just got conflated whiteness with being integrated. Sedated the creative, quitted the elated, demonized the frustrated, and moved to imprison anyone not white related while never addressing the issue. Tissue and sinew of the American fabric full stop lacks the ability to face the facts of its reactive fear of Black. Detracting from conversation of any psychological relation to a system THAT IS NOT MADE FOR THEM. Replacing the sin of physical ostracization with systematic slavery-based incarceration.

By the work’s end, the way Marshall reimagines mental illness as a “source” of musical inspiration in Insomnia’s My Closest Friend is clear. “This is just a story,” he says. “Something to help you sleep.” Instead of imagining the passions and suffering of mental illness as the necessary cost of “great genius,” for Marshall and Dent the spectrum of intersectional ways that the world deems us “unfit” is a shared pain and the solidarity of music-making is a way of making sense of that pain and perhaps showing a way forward—in a sense, collaborative musical performance as a sort of informal group therapy for both artist and audience. And indeed, here Marshall implores us: “Please get help.”

The performance was followed by a brief talk with Dent, Marshall, and Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychological Sciences and Counseling at Tennessee State University, Dr. Raquel Martin discussing the importance of mental health, particularly among young black men. In the talk, Martin expanded on a number of ideas from the performance but with particular attention to the issue of the cost of mental health care. With or without insurance, the costs of seeing licensed therapists or councilors are obscenely prohibitive, to say nothing of difficulty or cost in coordinating transportation to and from appointments or even being able to set aside that kind of time in the first place. While the theme of the night was the importance of getting help where possible, the question of exactly how often and for whom it’s possible frustratingly remains. With respect to this issue, Chatterbird sought donations in the name of the charity Black Men Heal, a non-profit “dedicated to providing access to mental health treatment, psycho-education, and community resources to men of color.” If you’re interested in donating to Black Men Heal, you can do so here.

At the Schermerhon

The Pastoral and La Malinche

On the third weekend of November 2022, the Nashville Symphony gave a marvelous performance of two very different pieces: Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 in F major, Op. 68 “Pastoral” and Gabriela Lena Frank’s Conquest Requiem, in the Laura Turner Concert Hall at the Schermerhorn Symphony Center.

Beethoven composed his sixth symphony in 1808 and it premiered in December in Vienna, just as winter was setting in. One could hear and feel the old composer’s nostalgia for a past spring in his first movement, “Awakening of cheerful feeling on arriving in the country.” Delicately, Maestro Guerrero coaxed the famous gentle theme from his string section with a beaming smile. When followed up in the woodwinds, the theme’s nostalgia articulates the pastoral setting. It is remarkable to think that the composer was simultaneously working on his dark and troubling fifth symphony as he wrote this essay on peace and beauty.

The second movement continued this beautiful setting, with the woodwinds providing the calls of Beethoven’s birds as the strings gently set the babbling brook. The reveling third movement, a Scherzo celebration, with its rollicking dance leading precipitously to the storm. It is a rush, and a fearful storm, but one of those enlightened storms that one sees from a distance, and its threat in the end is only of a refreshing shower. One must agree with Tovey that while Beethoven’s use of the piccolo here (played wonderfully by Gloria Yun) is not exactly one of its best moments in the repertoire, “…a real thunderstorm would be an expensive and inefficient substitute.” As the hymn of the final movement came to a close, it was clear what Beethoven meant when he described this work as “an expression of feelings” instead of a programmatic depiction. I had by this time completely forgotten the cold night outside the Schermerhorn.

After the intermission, Andrew Garland (baritone), Jessica Rivera (soprano) and the Nashville Symphony Chorus joined the orchestra for Frank’s Conquest Requiem. A massive and tragic work, somewhat derivative of Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, Frank’s work combines old and modern texts, languages, and genres. The main character, Malinche, according to Frank, was inspired by a true story. A skilled translator, she was “a Nahua woman from the Gulf Coast of Mexico who was given to the Spaniards as a young slave […] she would convert to Christianity and become mistress to Cortés during his war against the Aztecs.” Malinche was there when Cortéz met Montezuma, and the interpretation of the events that followed often hinge on her role as translator.

Her soprano role was sung with great nuance and passion by Rivera, providing an individual, humanizing voice to the tragedy, lending a voice to the conquered Aztecs. The chorus, wonderfully prepared by Tucker Biddlecombe and heard throughout, provides a moralizing interpretation that one would find from a Greek chorus. Malinche’s son Martín, sung with vigor, excellent diction, and an exacting intonation by baritone Andrew Garland, created a Janus-faced moment in that he is identified as the first mestizo, indicating a new era has come into being.

The performance was excellent, and I am sure the recording derived from it will garner an award. However, the idea of this narrative set within a Requiem does not sit well with me. I understand that Malinche is historically understood to be treasonous, but we don’t have to buy it. On the one hand, I certainly do not wish to celebrate the tragic repercussions of the encounter between the old and new worlds, on the other, I think I might be too optimistic of a person to discount the moment of contact entirely as a “cataclysm.” When Frank, in her notes, describes Malinche as having been “…variously viewed as feminist hero who saved countless lives, treacherous villain who facilitated genocide, conflicted victim […or] symbolic mother” I no longer see her appropriately depicted within a Requiem. Indeed, at her death, she was a free and wealthy woman with a family. For me, Malinche’s story is one of survival and resilience, an opportunity for a positive message of a complicated human who managed to stay alive despite the tragic events unfolding around her. For me, she might just be one of Beethoven’s heroes.

At the Frist

A Brief Intro to Nōhgaku: Ancient Japanese Drama

Some years ago, I witnessed traditional Japanese theater live in Japan. After years of teaching world and Asian music courses that featured the rich traditions of Japanese theater, a fellowship allowed for the thrill of seeing Bunraku (half-life-size puppet drama), Kabuki (colorful rambunctious live theater), and Nōh in person at the National Bunraku Theatre (Osaka), National Theatre of Japan and Kabuki-za (Tokyo) and National Noh Theatre (Tokyo). Music City residents now have the opportunity to experience a tempting taste of this latter delight at the Frist Auditorium.

On Sunday, December 4, 2022, the Frist Museum will host Theatre Nohgaku, 2–3 pm. In conjunction with their exhibit: “Weaving Splendor: Treasures of Asian Textiles from The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art,” this special performance highlights excerpts from Nōh, the most ancient of Japanese theatrical arts. Given the complexities of this art form, unlike anything in American culture, it seemed important to provide this little primer on Nōh.

One point to remember in the harried bustle of American life is that many of the stories are influenced by the contemplative practices of Zen Buddhism, so be prepared to relax. Nōh is a glacially slow style of drama codified in the twelfth century from influences as early as the eighth-century Heian era. It is one of the world’s oldest continuing styles of drama. On a stage with virtually no sets or props, masked characters use suriashi—elegant gliding motions also found in some martial arts—when walking. Highly stylized gestures, called kata, indicate emotions with delicate subtlety. For instance, in the shiori-kata, the actor’s head is slightly bent down and one or both hands (depending on the emotional intensity), slowly slide down in front of the mask’s eyes, indicating the tears’ direction during sadness.

Nōh is accompanied by a small chorus (ji-utai) and instrumental ensemble (hayashi). The Ji, a narrator seated upstage, represents the inner thoughts of the main character, the shite (pronounced “shee-tay”). The hayashi, seated downstage near the backdrop, consists of a high-pitched bamboo flute (fue, also known as the nohkan), the kotsuzumi (shoulder drum), ōtsuzumi (hip drum), and taiko (frame drum). Although it is the only melodic instrument, unusually, the fue’s rhythm is the emphasis.

The two main story types of Nōh are mugen and genzai.

Mugen plays feature a supernatural being, whether troubled spirit, creature, or demon as the shite. Typically, the waki (“wah-kee”), an important secondary character is a living traveler who meets the reincarnated version of the spirit who seeks its own freedom. In the play Ama, for example, a son traveling to perform a memorial ritual at the site of his mother’s death meets a woman who disappears after revealing herself as the incarnated spirit of his mother.

Genzai plays may also include a spirit, but the shite is always a live person. Sumidagawa’s shite is a mother whose kidnapped son is dead, but comes to her as a spirit.

There are also five main-character categories defined by whether the shite is a god, man, woman, madwoman, or creature.

The “god” plays, kamimono, like Takasago, often show the god as an elderly man and/or woman in the first half and the true embodiment of the god(s) in the second.

The “man” plays, shuramono, are tales of warriors seeking to escape the hell reserved for those who need redemption or forgiveness. In Atsumori, a genzai play named after a spirit, a warrior who has slain the beautiful youth Atsumori, renounces war, and becomes the monk Rensei. Praying for the soul of Atsumori, Rensei encounters his spirit and both find rest and redemption.

“Woman” plays, kazuramono, like Ama are kazuramono mugen plays where the main character is a woman who has died through loving self-sacrifice but returns as a spirit.

Plays like Sumidagawa are “madwoman” genzai (kyōjomono genzai) because the shite, a mother of a kidnapped son, is crazed by grief at his death.

Nue is a “creature” play (kirinohmono) featuring a creature shite left in the dark depths of the ocean after being killed. Its spirit prays that the moon can light its prison.

In the forthcoming event, Theatre Nohgaku, an internationally respected ensemble based in Japan will perform one individual dance, “Chū-no-mai,” serving dance’s traditional role as a palette cleanser, with excerpts from three mugen and one genzai.

Plot Synopses

Itzutsu

In this kazuramono mugen play, a Buddhist monk is traveling to a temple built by Lord Ariwara no Narihira, a famed poet. He stops at the well in a nearby village to rest. While there, as he prays for the souls of Narihira and his wife, Lady Izutsu, a local woman tells him the story of how Izutsu still seeks her unfaithful husband in the afterlife. The woman disappears after revealing herself to be an incarnation of Izutsu. In the final scene before the monk wakes from his slumber, Izutsu comes to him in a dream, seeking her husband, dancing while dressed in Narihira’s robes and headdress.

Ama

In this kazuramono mugen, Fusazaki, a young nobleman has traveled to an island to do a Buddhist memorial for his long-deceased mother. Once there, he meets a humble woman whose livelihood is diving to cut seaweed from the ocean floor. She tells him the tale of another diver who bore a son with a high court official. In order to obtain noble status for her son, she agrees to retrieve a jewel stolen by the Dragon King whose castle is at the bottom of the sea. Knowing she cannot escape alive, but the dragons fear corpses, she stabs herself, stores the jewel in the wound, then shakes the rope to signal the watchers to pull her up as she dies. Fusazaki recognizes the story as that of his mother. Before the humble woman mysteriously disappears into the ocean, she gives Fusazaki a letter in which she reveals herself to be an incarnation of his mother. She seeks freedom from the limbo in which her spirit is trapped. Fusazki recites the Lotus Sutra for her and she ascends into Buddhahood dancing gaily.

Sumidagawa,

This example of the kyōjomono genzai chronicles the tale of a mother who has traveled great distances trying to find her only child, a son kidnapped by child traffickers. Because she is so unkempt from her travels, the ferry boatman demands she prove her status in order to earn her fare. She recites a poem by Lord Narihira (see Izutsu). On the ferry crossing the Sumidagawa River, the boatman invites the passengers to a memorial for Umewakamaru, a child who had been left for dead by a slave trader exactly a year ago. As he died, he gave the villagers his parents’ names. The woman recognizes the child as her son and prays for his soul’s repose, invoking Buddha’s mercy through intoning chants of “Namuamidabutsu [I take refuge in Amida Buddha]” while beating a small gong. In the dark of night, her child’s spirit comes to her, but disappears when she tries to take him in her arms. As the sun rises, she is still sobbing at his tomb.

Hagoromo

This kazuramono mugen play tells the tale of Hakuryō, a fisherman (waki), who finds a gorgeous feathered robe hanging on a pine tree branch by the water. Planning to take it home, he is stopped by a heavenly maiden (shite) who cannot return to the Moon Palace, home of the Buddhist entity of strength and wisdom, without her feathered robe as her wings. He barters the robe’s return for a chance to see her dance in it. Once the famed “Suruga-mai” dance ends, she disappears beyond the distant peaks of Mt. Fuji.

From the Mabry Concert Hall at Austin Peay

Fisk Jubilee Singers: History Repeats Itself 150 Years Later

As we live in roiling tumultuous times, as hatred and violence grow, as we question the fellowship of our fellow citizens, we sometimes need respite, some way of seeing signs of goodness and hope around us, some way to commune with one another in peace and harmony. The Fisk Jubilee Singers provided such respite on October 30, 2022. Sponsored by the Clarksville Community Concert Association, at Austin Peay State University’s George and Sharon Mabry Concert Hall, a community of ages from infancy through the elderly, with a healthy sprinkling of college students, waited with anticipation for history to be made once more.

Sixteen attractive, talented, committed young people strode proudly onstage to carry on a tradition begun in 1871. At that time, when the university was only five years old, Fisk treasurer and music director, a white professor, ironically named George Leonard White, formed the original 8-member choir to tour, earning money to keep the fledgling university afloat. Consisting of newly freed slaves, the choir traveled with a pianist and a pastor, Henry Bennett. It was only midway through their maiden tour that they found their joyful name. In an act of true charity, they had donated their meager proceeds to victims of the Chicago fire, so they had no money to keep traveling and the dangers of travel for freed slaves was no small matter. Should they keep going or go on home. As we say in the South, they “prayed on it.”

Rather than wallow in discouragement, they regrouped, naming themselves “Jubilee Singers” after the Jewish Year of Jubilee, celebrating their recent liberation from bondage. And on this Sunday afternoon 150 years later, they liberated the audience from the cares of the world through singing joyfully of a time when cares were paramount, times when oppressive societal rules meant they had to hide their pain of the here and now, aim their happiness to the hereafter, a metaphor for the North.

Because the Singers are an a cappella ensemble consisting of current and recently graduated students, the group has gone through many generations, but this current iteration is one of the finest I have heard in decades. Dressed in neatly tailored black and white, they let the music tell the story of Jubilee Singers through the ages, never turning back, keeping the vow they made when they first took their name, singing: “Done made my vow to the Lord, and I never will turn back. I will go, I shall go, to see what the end will be.”

After this statement of purpose warmed up the audience, the soothing began with a lovely Thomas Rutling arrangement of “Steal Away.” The impeccable timing with no conductor and impeccable pitch in the close pianissimo harmonies were breathtaking. All they had of experience from their homes throughout the US, from Brooklyn and Queens in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Michigan, Missouri, Georgia, North Carolina, Mississippi, and of course, right here in Tennessee, all they wanted of majors from music to political science to math, was there in the community they have formed, the beautiful tones matching and blending in sweetness and strength, there for all to hear in their hearts. Often, after a delicate final chord, the audience would sigh in appreciation before bursting into applause.

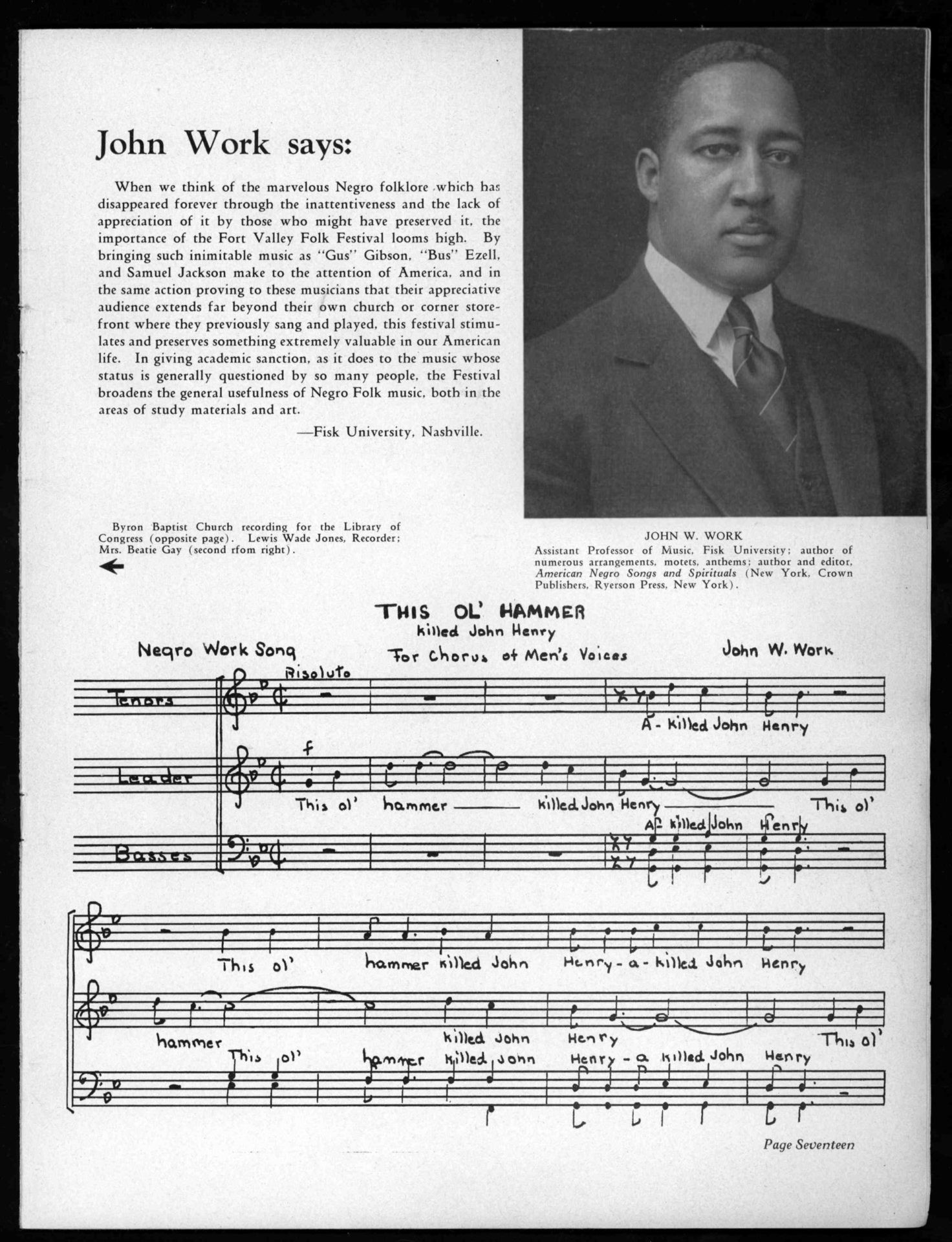

Many of the works were arrangements by the appropriately named John Wesley Work III. Work was one of the earliest of American ethnomusicologists, dedicated to preserving the music of his people for all time. In addition to his courses and administrative work at Fisk, he notated the music and arranged the tunes with aid from his mother, father, and grandfather, three generations of musicians.

The tradition of close relationships between the Singers, faculty, and alums continues in their current repertoire. Fisk alum Undine Smith Moore (“We Shall Walk Through the Valley in Peace”), like her predecessor Work, earned a graduate degree at Columbia University in New York, one of the few Ivy League schools that welcomed minority students. Paul T. Kwami (“Great Day” and “Down by the Riverside”), the recently deceased director of the Singers, also arranged for the ensemble. But though much of the music was uplifting, songs like “An’ I Cry” arranged by Noah Ryder with lyrics: “Sometimes I feel like I lost my soul again…an’ I cry,” reminded us of periods of hope-tinged hopelessness then and now.

The gorgeous Roland Carter arrangement of “In Bright Mansions,” the acme of a stellar program captured this dichotomy. When the choir held an extended chord that seemed intended for eternity, seamlessly taking breaths, as the lower voices repeatedly intoned John 14:2: “In my Father’s house are many mansions: if it were not so, I would have told you,” I couldn’t help but look at the beautiful skin tones that ranged from bisque to deepest mahogany, the hairstyles that ranged from short afros to waist-length braids. Each of these musicians could be stopped and harassed or worse just as their predecessors were ages ago, just because…

And yet, still they sing. They harmonize, they blend, they take solos, they back up their choirmates. They give something warm and loving to a world that does not always repay them in kind. They sing.

And with the generosity the group has shown since its inception, they serve the same respite function now as they did all those generations ago, over a century ago. Back then, they saved the bricks and mortar of Fisk with music of the spirit. Now, they use that music to soothe the spirit of the world. And although I feel a bit disconsolate about the fact that such respite is still needed, it is nonetheless wonderful that they are still here to provide it.

From the Nashville Symphony

Another Wonderful Night at the Schermerhorn

On the last weekend of October, 2022 the Nashville Symphony performed Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s 6th Symphony “Pathétique” Op. 24 (1893), along with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Concerto for Flute, Harp and Orchestra in C major K.299 (1778) and Nina Shekhar’s Lumina (2020), featuring the return of Vinay Parameswaran to the podium at Schermerhorn Symphony Hall in Nashville. For an excell

ent concert with a popular warhorse, the Symphony CEO Alan Valentine’s public statement that some patrons have given up on attending events at the symphony center because of traffic downtown and rowdy behavior on Broadway rang true–the hall was not very full and the din outside before and after the concert was typically LOUD.

The concert itself was wonderful. It opened with Shekhar’s Lumina. Detroit-born Shekhar is described on her website as “a composer who explores the intersection of identity, vulnerability, love, and laughter to create bold and intensely personal works.” The program for Lumina is given as exploring “…the spectrum of light and dark and the murkiness in between. Using swift contrasts between bright, sharp timbres and cloudy textures and dense harmonies, the piece captures sudden bursts of radiance amongst the eeriness of shadows.” It is a remarkable piece, who timbre and texture seems to be the primary determinant of form, much in the style of György Ligeti, but oddly more melodic. The intensity of the opening draws the attention in (a gesture powerful enough to transcend the cellphone ringing in the balcony seats) leading to a crescendo in a mass of sound. Acting Concertmaster Erin Hall’s leadership and crisp tone stood out in this piece wonderfully. The ending redrew the intensity in a brighter manner where one could almost glimpse Benjamin Britton’s sparkling detached ocean (the one that swallowed Peter Grimes).

The second piece of the evening was the Mozart, performed by the symphony’s own Éric Gratton (flute) and Licia Jaskunas (Harp). Mozart composed this Concerto for Flute, Harp and Orchestra on commission from a wealthy father (flute) who wanted a piece to perform with his daughter (harp). Notoriously, Mozart was not particularly fond of the flute, and the score indicates that he was not too familiar with the harp (5 finger arpeggios, no lush chords of glissandos, etc), Gratton and Jaskunas nevertheless gave a pleasant interpretation of this piece.

The final piece of the evening was Tchaikovsky’s epic 6th Symphony, the “Pathétique.” The piece, an anti-heroic essay that turns the ideal of Beethoven’s middle period on its head, substitutes a finale for the third movement, pushing the catastrophic slow movement to the end. Parameswaran’s gentle, nuanced and detailed interpretation was extraordinary. He loosened the reigns just enough in the third movement to let the band run. In the fourth, perhaps helped by the intensity of the opening Lumina, the audience sat riveted as the tragedy unfolded. In a night where the applause seemed to happen at all the wrong places, this final movement was permitted to fade into silence without interruption, and then an exhilarating ovation closed a fantastic evening.

As I left the Schermerhorn, I noticed the coolness and the smell of fall in the air, even through the din of “bro country” pouring from the “Florida-Georgia Line.” Crossing toward the pedestrian bridge, thankful for the free parking by Nissan stadium, my wife and I were almost run down by a passing pick-up truck. On the Seigenthaler bridge, tipsy youngsters on the rent-a-scooters were equally treacherous, things we had to watch out for even as we paused to take in our beautiful city’s skyline and the marvelous trees whose colorful leaves were set ablaze by the approaching winter. Costumed revelers sang and gaily chatted over the busker’s appeals for financial recognition. Maybe CEO Valentine has a point, or maybe, as my wife says, folks should “lighten-up?” Either way, it isn’t nor will it every be perfect, but the Music City does have its moments.

Voices Behind the Gauze: Nashville Opera’s The Medium

You really feel the passion when Nashville Opera’s Artistic Director, John Hoomes, pleads the case for the operas of Gian Carlo Menotti. In his program note for the Nashville Opera’s new production of Menotti’s phenomenal and eerie The Medium, Hoomes recounts defending the composer’s honor when challenged by “an earnest, yet self-important, opera snob” at a discussion panel some years ago. Why all the controversy? “He wrote some beautiful, accessible operas that were loved by audiences and found great success,” he explains. “However, in the mid-20th century when most composers were writing more dissonant music, Menotti became somewhat of a persona non grata among serious classical music buffs.” Musicologist and serious classical music buff Joseph Kerman wrote highly critically of Menotti in his polemical 1956 book Opera as Drama. Not only did Kerman call Menotti “trivial” and “a sensationalist in the old style, and in fact a weak one,” elsewhere in the book he compares Strauss’s Salome and Menotti’s The Medium to “drawing-room comedies.”

Though Kerman saw Menotti as “belong[ing] to another era,” it’s hard to say his critiques really had anything to do with the composer’s penchant for tunefulness and tonality. An entire chapter is dedicated to Kerman’s love for Mozart’s operas, after all, which certainly can’t be said to lack either quality. Instead, as the title of the book suggests, Kerman was concerned with the dramatic potential of operatic music, which could theoretically express itself in any style. It seems Kerman saw Menotti’s works primarily as dramatic failures rather than musical ones. For a number of reasons, especially in the case of The Medium, it’s worth coming to Menotti’s defense here too. Not only is his music in turns lovely and unsettling, the drama of Menotti’s The Medium is subtly rich and largely concerned with the nature of opera itself.

The story takes place at the parlor of Madame Flora, a cruel, often drunk woman who performs phony séances. Monica and Toby are her two young servants/children (the exact nature of their background is left eerily vague). They run the show—Toby, who can’t speak, operates the smoke and mirrors while Monica evokes the voices of lost loved ones from behind a gauze screen. Act I lets us in on these characters and their scam. We learn of Madame Flora’s abusive nature and Monica’s love for Toby. Things come to a head when Madame Flora ends the night’s séance suddenly, screaming out that someone’s touched her. Now she hears the voices behind the gauze even when she’s alone. Things turn tragic in Act II as Madame Flora’s guilt and paranoia grow to a fever pitch and everything ends in blood.

Madame Flora’s descent into madness hinges on her obsession with what she can hear but not see. Another character in the opera, Mrs. Gobineau, has the opposite problem. When singing of how she found her two-year-old son drowned in a shallow fountain, she mourns “I never heard a sound/And when I looked…/And when I looked…/And when I looked…” Now she and her husband come to Madame Flora every week to hear the sound of their child laughing, which is really Monica, hidden away. The separation of the sound from its source seems to have some sort of otherworldly power—Mr. and Mrs. Gobineau claim to often feel their son’s hand on their cheeks.

“Acousmatic sound” is the term for this phenomenon where the source of a sound remains unknown. In his writings on film and film sound, composer and film theorist Michel Chion coined the term acousmêtre to describe the source of a particular type of acousmatic sound, specifically one where this obscured source possesses an intoxicating, enigmatic type of magic. Consider the Wizard of Oz, who loses his power over Dorothy and friends as soon as the curtain is pulled back and the mortal man is revealed. Disembodied sounds, Chion argued, have a unique power, at least so long as they can remain hidden.

The Medium is full of acousmêtres. There are the obvious ones, like the voices haunting Madame Flora, or Monica’s performances as part of the fake séances. But they show up elsewhere, in subtler ways. Monica’s waltz from the opening of Act II, probably the most well-known excerpt from the work, sees Monica literally giving voice to the mute Toby’s thoughts. We see her mouth moving and hear her voice coming out, but if we’re to understand her as the ventriloquist’s dummy for Toby’s thoughts, then who is the ventriloquist? The simplicity of the title The Medium is perfect. At first glance, it seems to refer to Madame Flora alone, but here we can see that it might just as easily refer to Monica, too. In Act I she sings of a certain locket while pretending to be the late daughter of another customer, Mrs. Nolan. Mrs. Nolan says she doesn’t have any such locket, but later it turns out to be real. Now she seems to “hear” what Toby’s saying, even if he can’t speak, and even if we can only hear it when she sings. Madame Flora might be a phony, but could Monica be the real thing?

But there’s another level where the title works. In Act II, Madame Flora attempts in vain to give her customers their money back and to prove to them she’s a fraud. “Look here, the lights/The wires to make the table move/The hidden microphone,” she says to them, trying her best to break the illusion. The distinctive theme that opens both acts suddenly appears, underlying Madame Flora’s confession in varying harmonic configurations. The appearance here of a motif that can best be described as The Medium’s “main theme,” right at the point that Madame Flora tries to break the illusion of her own stagecraft, draws sharp attention to the self-referential nature of the opera as a whole. Here we’re reminded, quite unmissably, that the emotional drama on the stage is its own kind of elaborate trick, while the orchestra is the literal “medium” through which that drama makes itself perceptible to us, channeling emotions and colors out of the air.

Menotti plays with this idea at various points throughout the opera, especially anytime Monica’s singing is diegetic. “Oom-pah-pah/Oom-pah-pah/Up in the sky/Someone is playing a trombone/And a guitar,” Monica sings at the start of her waltz, bringing the orchestra to life with her words. If in a moment like this, we’re supposed to hear the orchestra as being somewhere between a part of the opera’s world and a part of our own—the orchestra communing with the thoughts and feelings of its characters the same way Madame Flora claims to do with the dead—then perhaps Madame Flora’s auditory delusions and emotional breakdown aren’t the result of meddling with the world of the paranormal as she fears after all, but delving too deeply into her own repressed emotional one.

Alissa Anderson, singing the role for Nashville Opera, conveyed Madame Flora’s broken state in her final extended soliloquy at the very end of the opera quite well. Like with the rest of the work, what we learn about her past is vague and uncertain, but the few details of the “many terrible things” Madame Flora tells us she saw in her younger days are more than enough to give us a sense of why she drinks herself into an abusive rage seemingly nightly. While Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw (1898) or the 1944 film The Uninvited are obvious forerunners, it’s remarkable that Menotti’s opera prefigures so completely the psychological horror and “ghosts of the past” realism of Shirley Jackson’s novel The Haunting of Hill House (1959) or the slew of thrillers in the ‘60s styled on Robert Aldrich’s Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) and Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964).

In a scaled-down work like this, with only a handful of characters, a single set, and relatively little grand spectacle to fall back on, it’s even more important than usual to have a solid cast to carry the weight of the drama, which was certainly the case for the Nashville Opera’s production. Joseph Mobley’s wordless performance as Toby made quite the impression, while Helen Zhibing Huang as Monica and Kaylee Nichols as Mrs. Nolan gave especially affecting performances. The at-first-glance simple stage design by Randy Williams made great use of the smaller space of the Noah Liff Opera Center and even managed to hide a number of delightfully spooky practical effects that transformed the stage into an old-school haunted house at a number of key moments. And on the costume front, the 1940s costumes gave the setting a retro vibe, which while not necessarily present in the original work, where Menotti writes that“”[t]he action takes place in Madame Flora’s parlor in our time,” the sense of nostalgia that accompanies it did ultimately amplify The Medium’s themes of the eternal ghosts of the past. Another nice touch was the white, ruffled-collar shirt Toby wears in Act II, which gives Madame Flora’s bribing offer to buy him “a brand-new shirt/Of bright red silk” an even more sinister tone by the opera’s conclusion.

But now to the question of Menotti’s “accessibility.” The darkness that stems from Madame Flora’s memories of the dead manifests itself in a dissonant, mostly declamatory singing style often closer to Sprechstimme than recitative. All of the other characters seem capable of accessing an expressive, emotional tunefulness in their melodies, but even Madame Flora’s attempts during her final soliloquy to sing “Oh Black Swan,” which Monica sings to her at the end of Act I to calm her from her fitful state, falter and break off as soon as they start. Somehow the magic of her séances work for everyone else—even when the tricks are revealed, her patrons insist their encounters with the dead have been real all along. They seem to be perfectly at peace not despite but because of the acousmatic powers of the séance’s fakery. It’s only Madame Flora’s cynical insistence on finding and quelling the source of the disembodied voices—of unmasking the acousmêtre of her own making—that lead her down her tragic, destructive path. It isn’t delusion that causes the Gobineaus and Mrs. Nolan to see and hear their lost children. On the contrary, in the absence of the séance’s fiction, the only thing left is a cold, echoing emptiness that drives Madame Flora mad. It’s easy to see why someone who loves Menotti so much, and above all for his commitment to tunefulness in the face of mid-20th century Modernism, would be attracted to this piece. Menotti shows us the dual-natured power of opera as drama in The Medium and argues that its supernatural insight into the immediate emotions of its characters becomes something altogether terrifying and ugly in an attempt to rationalize and analyze it. Small wonder that Joseph Kerman didn’t like the guy.