The MCR Interview

Interview with Giancarlo Guerrero

Daniel Krenz: Good afternoon, it’s a pleasure to speak with you today! I’m really looking forward to this concert. It seems to be a perfect picture of what the Nashville Symphony is all about: there’s American music, new music, we’ve got Grammy connections, and live recordings. I’ve heard you talk about how programming a concert is something that you take very seriously and deeply enjoy. How did the program for this concert come about?

Giancarlo Guerrero: Well, the fact that we’re having our good friend Paul Jacobs coming and championing our wonderful organ in the Schermerhorn, which is one of the most amazing instruments; I know it’s one of the favorites for audiences, when we get to showcase and continue our project of recording great American organ concertos. Which I think has been long overdue and who else but the Nashville Symphony to do this. By having these two new works on the program, I felt that it was a wonderful thing to pair them with one particular work, which is pretty much my absolute favorite from the very beginning, and perhaps the first great American tone poem, which is An American in Paris. And I’ve always been of the belief that whenever you put these new pieces with one of what I call the “Warhorses,” the Warhorse has the new possibility of sounding fresh again, because you’re hearing it through the prism of all these new works. So, I felt that this was a wonderful opportunity to play this piece. You know, sometimes An American in Paris doesn’t get its due; sometimes it’s moved to pops concerts or to concerts that are not the main subscription series, and to me it’s perhaps the first great American tone poem from the 1920’s that kind of opened the door for all the great music that came afterwards with Bernstein and Copland and Barber and everybody else. But it was George Gershwin —ironically a Broadway composer— who basically set the standard for American classical music.

DK: When you are performing a piece that the audience is familiar with and you have performed multiple times like An American in Paris – is there anything that you do in your preparation to keep it fresh, or to change it, or to try something different from last time you performed it?

GG: I always get a new score whenever I perform a piece that I have done before. I always buy a new score and, if possible, buy a different edition, so even just the score itself looks different, and from that perspective, I try to approach it as if I’ve never heard the piece. Which is basically impossible. I mean, a piece like this, that not only have I conducted it, but I’ve heard it live, I have many recordings of it, you turn on the TV and excerpts from it are being played. It comes with baggage, but the fact that I try to continue to disconnect myself from the past and look at it, even in just a different score where even the font is different, makes me look at things very very differently. I start discovering things that I may have perhaps overlooked before or things that maybe I put an emphasis on before but now I put an emphasis on other things. It may be rhythm, it may be colors, it may be particular instrumentation. So it’s always a discovery and I think that is one of the most important things about what we do, because we are so steeped in tradition. But even with tradition you have to have flexibility. And that applies not only to George Gershwin’s An American in Paris; it applies to Johann Sebastian Bach, it applies to Mozart and Beethoven and everybody else. Because the world is changing, why shouldn’t performances and attitudes towards it? I feel that it many ways it’s a rediscovery of a piece under different circumstances. And remember, post-COVID, it’s almost like starting with a blank slate in many ways. And every time we get to play it’s a reminder of what we almost lost. Once again, we’re here celebrating this music which is eternal. And for me, what better place to do it than in a program that showcases two brand-new American works specially written for the organ.

DK: I’m particularly excited for this one because I’ve heard some pretty stiff performances of Gershwin in general, but you and the Nashville musicians always seems to nail the style.

GG: Well the big reason for that is that we take it as seriously as we take a Beethoven symphony or a Brahms symphony. As I said, this is one of the great American tone poems and perhaps the first one. It opened the door for many others and because of that I think it’s an absolute masterpiece that deserves to be in every great program of every major orchestra, not only in the United States but all over the world.

DK: Pulse, the first piece on the program, was first premiered with the Composer Lab Program back in 2019. Can you talk a little bit about the Composer Lab Program and what it’s like to workshop a piece live with the composer right there with you?

GG: Like you said, this program kind of encompasses everything the Nashville Symphony is all about. Over my tenure here we have been championing all the great living American composers, all of them very well established, Pulitzer Prize winners and Grammy winners and what have you. The next natural thing was discovering the next generation of great American composers. The Composer Lab was basically designed to do that. We bring these young composers —who are just maybe out of school, just getting started, and who perhaps need that extra push— and the Nashville Symphony and myself as a conductor are more than happy to give them a voice, bring them to Nashville, and put them under this lamp, basically, five of six of them at a time every two years, where we perform their music. And at the same time, they get to meet with our players and talk with professionals in the business, and understand what it is like to be a professional composer in the 21st century: How do you promote your music? How do you publish your music? So it’s not just playing their music, it’s a whole thing together that eventually, as they progress —and many of them have gone on to great careers— they will always look back on the Nashville Symphony —and the Nashville audiences, by the way— that gave them the opportunity to have their music performed. The last one that we did before COVID produced, in my opinion, five incredible, great works by very mature composers at very young ages. One of them was this composer, Brian Nabors. The whole orchestra was completely fascinated by this piece. I immediately decided that it deserved to be on one of the subscription programs. And of course, we had it programmed in 2020 and I don’t have to tell you what happened then! So here we are. It’s a postponement and finally, we got a chance to put it in here. So it’s a wonderful combination of having all American composers, one of them a Nashville Symphony discovery in the case of Brian Nabors, then Christopher Rouse, a great friend who unfortunately passed away not long ago. Wayne Oquin, who’s a new addition to our long list of great composers, and of course, the immortal George Gershwin.

DK: Your relationship with Paul Jacobs has been very fruitful with a handful of Grammys, and I know you’ve collaborated on a number of occasions. How did you and Paul first meet?

GG: Well it was one of those arranged marriages, we first worked together in the Cleveland Orchestra. He was the assigned soloist and I was the assigned guest conductor and we immediately hit it off. I mean, let’s face it, Paul Jacobs right now is perhaps the most important American organist on the scene, by far. Not only is he an amazing performer, but he has inspired all of these great composers, for the last ten, fifteen years, to write organ concertos specifically for him. The best comparison I have is to go back a hundred years ago, when Mstislav Rostropovich became the great cellist of the 20th century, and pretty much every great cello concerto of the 20th century was https://www.musiccityreview.com/wp-admin/options-general.phpwritten for him. So in this case it is Paul Jacobs doing the same thing for the organ. And remember, this instrument is usually very conservative, usually related to churches and sacred music. The fact that nowadays he’s championing all this of music that has been written specifically for him and can be performed in concert halls is an absolute miracle. And seeing we have this amazing instrument —which, by the way, is not available to many orchestras; if you go to New York, neither Carnegie Hall or the New David Geffen Hall have an organ— so they’re not able to do this, but here in Nashville we have this ability to perform and champion this music. This is part of a long project that Paul and I have been talking about, of not only releasing this, but continuing to commission more composers, as they come along, to continue expanding the repertoire for organ, just the same way that Rostropovich did for the cello a hundred years ago. And he’s the right person for it. In fact he’s such an amazing virtuoso that there are no limits to what this guy can do. For me it has been one of the best projects that I’ve been involved in. In my time in Nashville, with all this championing of new concertos that Paul Jacobs has brought in. By the way, this will wrap up the CD that we started before COVID when we recorded the Horatio Parker concerto, which is a late 19th century piece. Horatio Parker was Charles Ives’ teacher at Yale, interestingly enough. So yeah, it’s not only looking at the new pieces but at the same time bringing back some of this amazing American organ music that was written a long long time ago, that in many ways has been neglected.

DK: I’m really looking forward to it. I think it’s a fantastically programmed concert. Thank you for taking the time to talk about it.

GG: I’m sure you’re going to love this concert and I’m very much looking forward to it.

Chamber Music at the Schermerhorn:

The Elliston Trio plays Haydn and Ravel

On a cold February night, the Elliston Trio played a program of Franz Joseph Haydn and Maurice Ravel to an intimate audience at the Schermerhorn Symphony Center. Founded in 2016 the trio is made up of Matthew Phelps (piano), Erin Hall (violin), and Keith Nicholas (cello). They have made numerous appearances around Nashville since their inception and have become a staple of the Schermerhorn’s Chamber Music Series. This concert, on February 1st, was a free concert open to the public and presented a great contrast between two different composers look at the Piano Trio. I had the privilege of interviewing Matthew Phelps before the concert (which can be read here) where he described the distinctions between Haydn and Ravel’s treatment of the instrumentation.

In the Schermerhorn’s past Chamber Music events the audience was invited to sit on stage with the performers and look out onto the hall. This was not the case for this evening as the audience were spaced out on the main floor of the hall and the performers came to the edge of the stage. Microphones annoyingly obscured the view of the trio, and the back of the stage was cluttered with the remnants of a full orchestra rehearsal. The programs that the audience received were single sheets of paper cut in half with the front displaying the program and the back half was a 100-word land acknowledgement asking for donations. These factors, and the entrance to the hall being confined to one doorway, made the whole event feel like it was not receiving the attention that it deserved. This was a shame because the playing was quite phenomenal.

Opening the program was Haydn’s Piano Trio in C Major Hob. 21. Haydn wrote over 40 piano trios and this was written during his second trip to London where he was heralded as the world’s greatest living composer. This piece is perhaps not the biggest piece of evidence to support that claim, but it is full of all the life, joy, and humor we expect to find in Haydn. The second movement in particular, is a slow beautiful melody. I am so accustomed to hearing the power of the full Nashville Symphony in this hall, but the Elliston Trio did not sound small at all. The lyrical string playing of Erin and Keith balanced tremendously well with Matthew on the piano. This piece, lasting around 15 minutes, is a perfect three movement miniature of the larger scale forms we see in Haydn’s symphonies.

The final piece was Ravel’s Piano Trio in A minor. This is a four movement 30 minute work that has its roots in Haydn’s Classical era. There are two movements in Sonata form, a passacaglia, and a scherzo, yet each movement is unmistakably Ravel. This is a work that Matthew Phelps described as “musically and technically difficult” and it was obvious from the first few minutes that we are in a completely different sound world than the Haydn. Ravel seems to be searching for the maximum amount of expression that he could get out of the instruments and he asked for techniques like harmonics and pizzicatos to highlight that expressivity. My largest takeaway from this piece was how sensitive the Elliston Trio was to Ravel’s demands. The players were able to turn on a dime to let another member take the lead.

After the music Keith Nicholas took the microphone and asked the audience if they had any questions. A twenty-minute discussion ensued covering topics such as the music, the group, preparation for the performance. The Q&A format fit quite nicely into the community event style. Overall, it was a remarkable performance making me excited for more Chamber Music events in the future. As I walked to my car reflecting on the performance, I heard several animated college students figuring out what chamber repertoire they should like to play after hearing the professionals do it.

OZ Arts presents

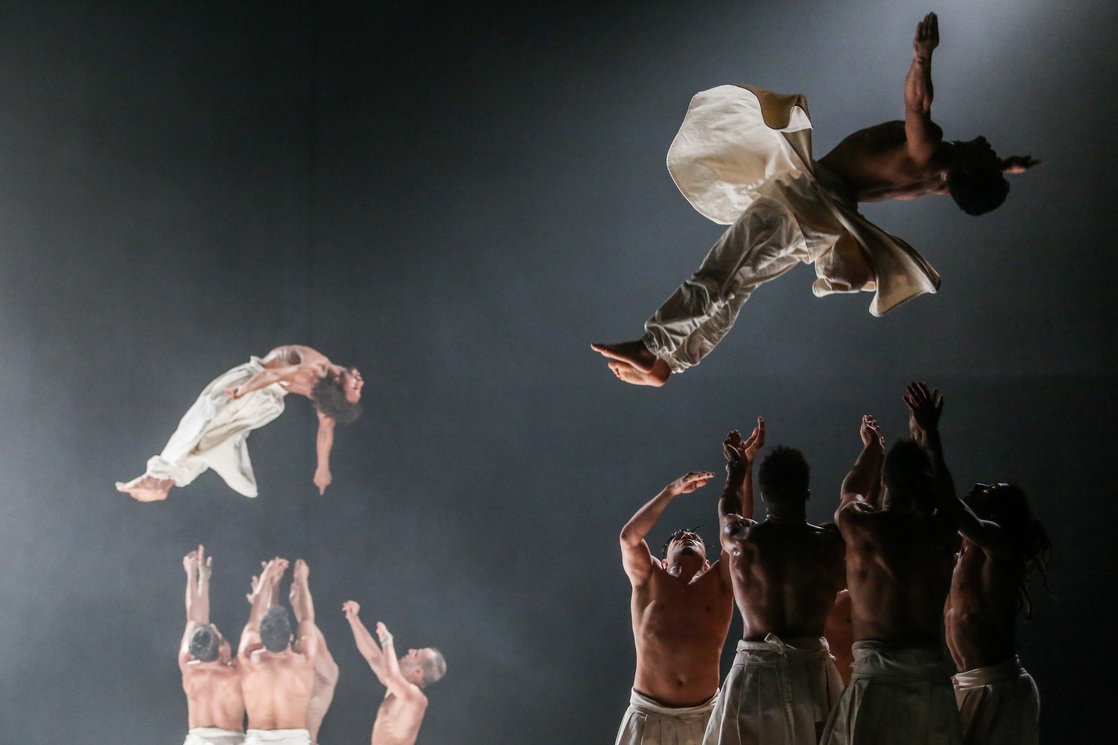

Compagnie Hervé Koubi

On Thursday February 2nd, OZ Arts Nashville opened their season with What the Day Owes to the Night, performed by the dance troupe Compagnie Hervé Koubi. The evening began with a short introduction of the upcoming season at OZ Arts and then a short talk by the choreographer Mr. Koubi himself. He explained that he was born in the south of France and after a conversation with his father discovered that his familial roots stretched back to Algeria. The name of the work, What the Day Owes to the Night, is the same name of a 2008 novel written by the Algerian writer Yasmina Khadra. The novel follows the life story of a young man from Algeria in the 1930’s.

What the Day Owes to the Night was written in 2013 and has since earned Koubi an international reputation. A dozen dancers participate in this production and the dance ranged from hip-hop to traditional styles. Koubi explained before the piece that his dancers are street dancers from all over the Mediterranean: Morocco, Italy, Egypt, and more. The music was also wide ranging, featuring excerpts from J.S. Bach’s Passions to Sufi traditional music. The show began with the stage in complete darkness. A barely audible gong began to ring rhythmically as dim shapes slowly moved onto the stage. Over the course of many minutes, the lights were gradually brought up while the dancers slowly swayed and bent on the stage. It was a masterful depiction of the sunrise.

As the lights came up the music shifted to computerized sounds and we saw all twelve dancers dressed only in white flowing pants. Soon some dancers broke off into more acrobatic motions – backflips and aerials – while some seemed to spin impossibly fast while doing a handstand. These overt athletic gestures always elicited a gasp from the crowd as these muscular men dazzled the audience. These gestures were no doubt impressive, but over the course of the 60 minute show they lost a bit of their luster. After the breathtaking opening I was ready for the immediate appeal of What the Day Owes to continue throughout. However, there were many moments where the story failed to grip me in the initial ways it had.

Despite being unable to sustain itself for the length of the program, the work is nevertheless a bold statement. The commanding moments of the work are so overwhelming that it is hard to figure out a stronger depiction of energy and power in dance. Perhaps part of that is the experience of seeing it live. There is something about a performance such as this where it truly does not feel as if it can be recreated. If I listen to a performance of Beethoven I feel as if many other orchestras can replicate a similar experience. But there is something about being in the room and seeing the sweat from these performers that is enthralling. When one dancer leaps off of the backs of other dancers there is a moment of real risk experienced collectively. This is the sort of experience that makes for an effective art work. There are only two more chances to see Compagnie Hervé Koubi this week and I would recommend the experience to everyone. For more information and to purchase tickets please visit https://www.ozartsnashville.org.

The MCR Interview:

Interview with Matthew Phelps of the Elliston Trio

This Wednesday February 1st, the Elliston Trio is performing a set of piano trio’s by Joseph Haydn and Maurice Ravel at the Schermerhorn Symphony Center. This is a free concert that is open to the public. Please visit the website here to reserve your seats. Ahead of this event Music City Review’s Daniel Krenz sat down with pianist Matthew Phelps to talk about the program.

Daniel Krenz: Good afternoon Matthew, it’s great to speak with you today.

Matthew Phelps: My pleasure!

DK: I suspect most of the people that are going to come to this concert are probably just familiar with the symphony as the huge, full symphony, so this chamber concert might be new for a lot of people. What is the rehearsal process like for putting together this chamber concert?

MP: Erin Hall, Keith Nicholas, and I have played together —we were just thinking about that this week actually— for eight years. We honestly can’t believe we’ve been playing together that long. So that definitely affects the rehearsal process. It’s very different now for us than it was even three or four years ago. Because when you first start playing together a lot of the rehearsal process was really getting to know each other and getting to know how to follow each other and how to communicate with each other while playing together. Now that that’s a lot more second-nature, the rehearsal process for us is a lot more —especially in the Ravel— about trying to find the right sound. Because the Ravel uses a lot of effects and uses a lot of ambient sound, more than you would think from a chamber music piece. A lot of the rehearsal process has been trying to find the right sound for things like pizzicato and harmonics. And to get it to work at the tempo that Ravel asks for, [chuckles] which is not friendly. It’s a pretty quick tempo. I will say, and maybe more specifically to your question, like when you’re dealing with a big orchestra, the string players are going to be handed bowings and be expected to execute, whereas I’d say that those kind of decisions are much more organic in our rehearsal process. Erin and Keith are talking about bowings, talking about how did they want to play this. It’s that kind of stuff. It’s a lot of communicating and trying to work that stuff out really well.

DK: I really like the pairing of the Haydn and the Ravel. How did the process of programming those pieces come about?

MP: I think Keith picked the Ravel and Erin picked the Haydn. We usually take turns picking pieces, it just kind of depends. We have generally chosen pretty heavy romantic trios. We have played Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart, Dvorak, and the Tchaikovsky trio, which is a massive piece.

We played the Joan Tower which was really a great experience. It just kind of depends. Usually we just make a suggestion and we go ok, yeah, sure, that one worked. The Ravel has been on the list for a while and we just shied away from it because it is really difficult. It’s musically difficult on top of being technically difficult. The Tchaikovsky is technically difficult but not musically difficult. The Ravel is musically and technically difficult. And it’s just a nice pairing to go with something that we could do comfortably. And we’re taking this program to North Carolina in a couple weeks to play at UNC Chapel Hill and I think we’re adding the Brahms C Minor Trio which we’ve played before.

DK: The Brahms will be a great addition!

MP: Yeah, it’s a great program. I mean the Brahms is heavy. The Ravel is heavy in its own way. It’s interesting. It’s a lot more esoteric than you would think. I think of La Valse and the G Major Piano Concerto and a lot of the solo piano works as being complex but lighter. The trio’s heavy. Really heavy. And even the Left Hand Piano Concerto, I don’t think of it as heavy and esoteric as this, even though I think there are a lot of similarities between that and this piece.

DK: Yeah, the left hand piano concerto is probably the closest example I can think of to something like this.

MP: I tried to learn the Left Hand Concerto but I just decided it was dumb. I have two hands, why can’t I use both hands? [both laugh]

DK: For the Haydn trio, I’m really interested in the piano in the instrumentation here. I think back to something like the Brandenburg Concertos where the harpsichord/piano is treated as a continuo instrument, but Haydn has really elevated it and taken it out of its continuo position. So how do you —especially with you being the only non-string member of the trio—feel that Haydn treats the piano within this context?

MP: Well I think with the Mozart trios it feels a little more like a concerto with string instruments. And the balance between the strings and piano in the Mozart is not so good. It’s very much a piano trio, and the strings just play along. Haydn, being much more of a string player, I think gives a lot more interest to the strings and I think it’s is much more unified ensemble than I think you find in Mozart. One of the things that I think is interesting about Haydn that you don’t find necessarily in Mozart is just how much the material meshes together. For example, in the Haydn trio the violin will play the melody but the piano will often play in the same rhythm, maybe a third lower. It’s still the same rhythmic and motivic gesture and everything. It’s a lot more organically unified. Whereas Mozart, you’re playing runs while the strings do a simple accompanying rhythm. I think Haydn treats the ensemble a lot more organically. So the piano part’s interesting, especially in the second movement. The second movement the piano is treated really melodically. But not so much in the first and third movements; I mean there are melodies but they’re with the strings. The strings are doing the same material. It’s a little different.

DK: Part of the reason I enjoyed the pairing of these two so much is because the piano trio to me, as just a genre, is very rooted in the Classical era. Ravel takes it and writes a piece where the first and last movement are sonata form, we’ve got a passacaglia, we’ve got a scherzo; it seems very rooted in that tradition, but it’s pretty characteristically Ravel. How do you see the differences between the way that Haydn treats the piano and the way Ravel treats the piano?

MP: I think there’s actually a similarity in that, we talked about it being kind of a unified ensemble in the Haydn, that is certainly really apparent to us in working on the Ravel that Ravel wanted each instrument to be treated independently and as substantially as the other ones. So of course the piano part’s huge because it’s Ravel and he was a pianist, but when you analyze the music and how it’s constructed, the violin part is as important as the piano part at any moment, as is the cello part. He really works very hard to make sure the texture is not overbearing, so you can hear everything. That’s the most important thing to understand in regards to all the instruments with the Ravel; he really writes it so that each instrument is discernible. Which is why composers find it so hard to write piano trios. Piano trios are significantly more difficult than other types of chamber music because of the balance problem. Ravel really works hard to solve that and I think that’s how you have to approach the piano part. I think in the last movement there are a couple spots where he’s not successful, frankly, in solving the balance problem. And that has certainly been part of the rehearsal process also.

DK: Do you have a personal favorite moment out of the program?

MP: My favorite moment in the program is that moment after which I’ve played the hardest part right. [laughter]

DK: I’m assuming that’s in the Ravel?

MP: The Ravel is difficult, yes, there are some amazing moments in the Ravel. I think the end of the Ravel is very exciting and it’s taken me a while to decide that. It’s difficult, it’s dense and some of the stretches are uncomfortable. We had to end rehearsal because my hands couldn’t take it. But with all that said, there are going to be a zillion spots in the Ravel where I could say “that’s cool.” I actually think my favorite part of the whole program is the middle movement of the Haydn. That’s really sublime. Haydn’s not always melodic; it’s melodic. It’s just really pretty.

DK: I’m really looking forward to it. Thank you for your time.

MP: No problem Daniel!

To get your free tickets to the performance please visit the Nashville Symphony’s website.

*This conversation has been slightly edited for clarity.

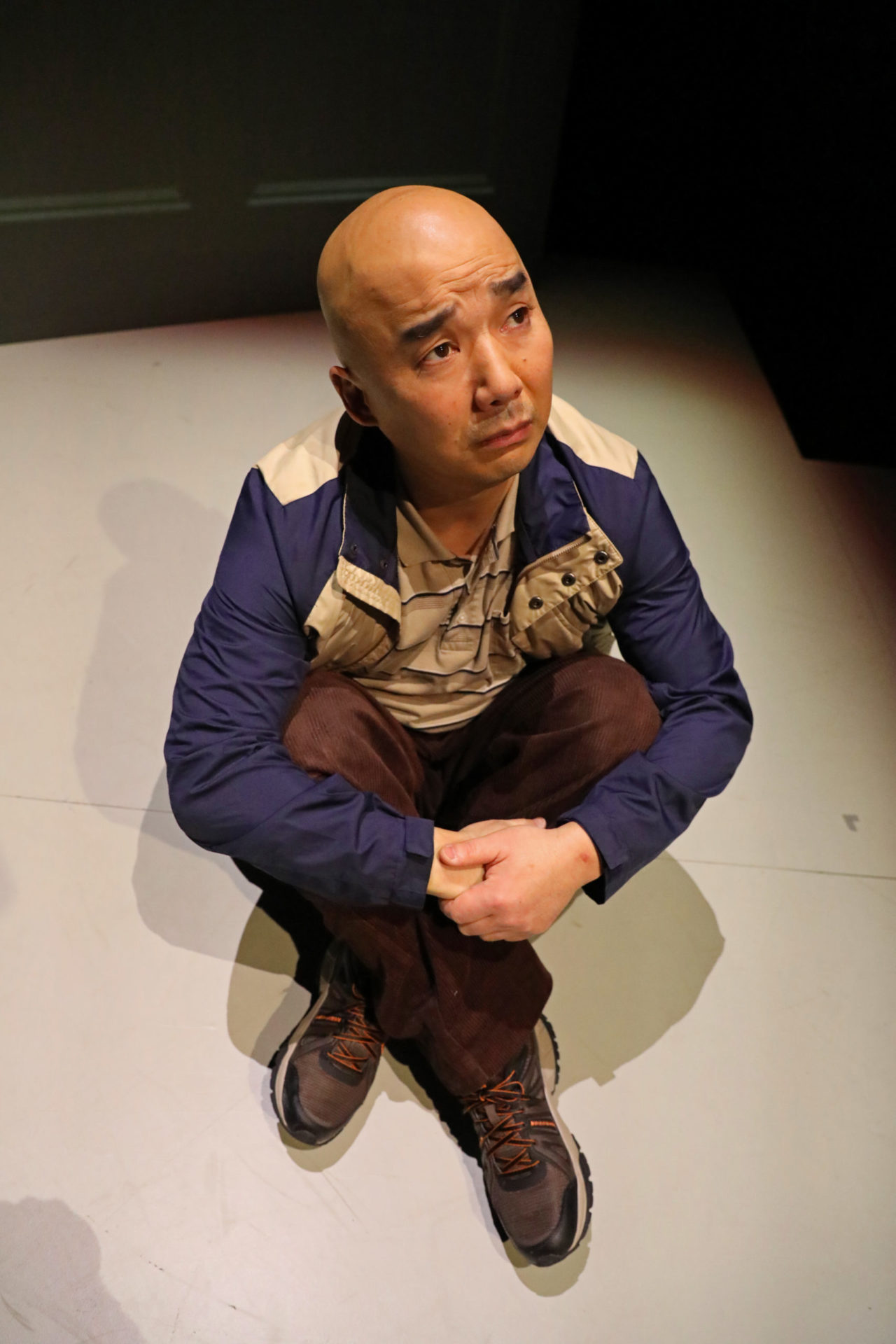

From Nashville Opera

STUCK ELEVATOR: AN INNOVATIVE LOOK INTO THE STRUGGLES OF ASIAN-AMERICANS

Not many people know the true story of Ming Kuang Chen. In 2006, a Chinese immigrant living in the Bronx was sent to a high rise apartment building to deliver a meal. While riding back down, the elevator breaks, and drops more than 30 floors before getting stuck just below the 4th

floor. His cries over the emergency intercom are either ignored or misunderstood, and, as an illegal immigrant, his fear of getting caught only grew.

This story becomes the basis of Stuck Elevator. A challenge only known to a portion of America’s minorities, the struggle of surviving as an undocumented immigrant in the states is humorously and creatively portrayed in the opera. Composed by Byron Au Yong with a libretto by Aaron Jafferis, the opera begins with the scene where the main character Guang (a portrayal of Chen) is getting into the elevator to deliver his food. After he falls, the scenery switches between the harsh reality he now faces along with the comedic flashbacks to his family and friends.

The opera was performed at the Noah Liff Opera Center. While much smaller than anticipated, it was well decorated with a welcoming atmosphere. A winding staircase led up to a crowd of men and women in suits and dresses. A clever detail I loved was a setup of a Chinese takeout box spilling out fortune cookies; I imagine it was how Guang felt as he fell down the elevator. Entering the performance hall, there were very few empty seats. I’d say most of the audience was older, although there were sprinkles of the younger generation here and there. The composer Byron Au Yong and librettist Aaron Jafferis sat a few rows behind me. I spoke with them before and after the opera; they were both very kind and happy to have their piece being performed.

The music is its own unique blend of rap, rock and classical, an innovative blend I haven’t seen in any other opera before but works very well with the plot and characters. Along with the singers were a drummer, two violinists, a cellist, and other instruments. I was surprised to see what I thought at first to be limited instrumentation, but as the opera started it became apparent that a large ensemble was not needed to tell the tale. It felt almost like I was on a seesaw sometimes; one scene would have slow, melodic and melancholic strings, and the next would be a rap battle. Like the music, the actors were also extraordinary. The deep, rich voice of Julius Ahn (Guang) beautifully portrays the main character’s sorrow and fear as he sways between reality and imagination. Soprano Ivy Zhou plays Ming, Guang’s wife still living in China as he works to support her. Her voice is perhaps the most captivating, floating above the stage and carrying life with it.

Perhaps the most important aspect, and message, of this opera is its portrayal of the struggles of Asian-Americans. Like other minorities, Asian-Americans face much discrimination in the United States, with many being harassed or ignored in the same manner as Guang. Undocumented Asian immigrants’ struggles are compounded by their lack of proper documentation and facing any harassment or attempting to fight would only lead to potential attention from officials. Guang’s entering and leaving of the elevator in silence was an excellent way to represent an otherwise invisible issue to the majority.

After the opera, my partner and I stayed behind to listen to the performers and writers talk about their performance and the experience of making the opera come to life. Yong revealed that the idea for the opera came to him back in 2005. He had been living in New York at the time and had heard of several cases of Chinese food delivery men who had gotten hurt on the job. Originally kept at the local level, Ming Kuang Chen’s story was originally a missing person’s case before he was freed from the elevator. Soon after he was freed, outside newscasters reported on the ordeal and the story went national. While Yong had never worked in food delivery, he related to Chen’s story because while apartment hunting, he was often mistaken as a deliverer. Both the performers and writers agreed that Stuck Elevator is a story meant to uplift the voices of immigrants, with some of the crew noting it as especially important to Asian Americans and the prejudice they face.

At the Nashville Symphony

The Chestnuts Have Their Day at the Schermerhorn

On Saturday, January 21, 2023 the Nashville Symphony gave a splendid performance of three chestnuts: Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings, Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony. In this rather conservative (for Nashville) program, the ensemble was led by Associate Conductor Nathan Aspinall and joined by 2009 Van Cliburn winner and internationally celebrated soloist Haochen Zhang on piano.

The evening opened with the Barber, and it was marvelous. Barber, a wunderkind, was born into a very well to do family born in my hometown of West Chester, PA. He went on to study at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, where he developed an intimate relationship with Gian Carlo Menotti that would last more than 40 years. Written while he and Menotti were visiting St. Wolfgang, a small market town just outside Salzburg, Austria, the Adagio is perhaps Barber’s most famous piece. In performance, Maestro Aspinall has a very detailed approach, but also gives attention to the large, sweeping gestures; a sine qua non for any successful performance of this famous lament. At the end, the moment was appropriately quite heavy, and I wondered if Zhang might be able to lift us up for Rachmaninoff’s masterwork.

Rachmaninoff’s Second Concerto was a hard-fought masterpiece for the great Russian pianist and composer. Coming off the epic failure of his First Symphony, he was suffering from writer’s block, depression, doubts that we would certainly call imposter syndrome today, and a group of important, but quite critical admirers including the great Russian composer César Cui. A friend of his family sent him to Nikolai Dahl who specialized in hypnotherapy. Through a period of affirming treatments, (the phrases used in trance were: “You will begin to write your concerto … You will work with great facility … The concerto will be of an excellent quality”) Rachmaninoff began to compose again and the piece found a premiere in November of 1901. It has since, rightly held an important place in the virtuoso piano repertoire.

Zhang began the piece—those famous, stirring, dark chords, with an exuberance and enthusiasm that was infectious. As the orchestra entered the I realized the wisdom of Aspinal’s programming. Zhang would help us to climb out of Barber’s sad gloom. My favorite part was the second movement, with the interaction between Zhang and the woodwinds, supported by the circulating arpeggio. After the blistering final movement’s cadenza, and the sharp final chords, the audience absolutely leapt to their feet. After several minutes of ovation, Zhang returned to the bench and gave us an encore with a Chinese Folk melody in honor of the lunar new year. Thank goodness for intermission because emotionally, I was spent and needed to regroup!

After the break, Maestro Aspinall tucked into Tchaikovsky’s fourth, sometimes called “The Fate” after the famous horn motive that opens the first movement. Tchaikovsky, who was homosexual, had finished this composition just after the failure of his disastrous marriage to a woman. He himself described the first movement and its relationship to fate as “…the fatal power which prevents one from attaining the goal of happiness….” Given the homophobia that Tchaikovsky had to deal with throughout his life, one would expect the movement to end with calamity, but instead, it is victorious.

In Nashville, where we have a horn section that can compete with nearly anyone, the motive was terrifying and awesome. Aspinall showed a huge measure of patience, slowly allowing Tchaikovsky’s melody develop across the orchestra in bits and pieces, gradually assembling into this huge movement (the movement lasts nearly as long as the other three movement combined). The second movement brings back the primary theme of the first, but in a gentle oboe solo which was played with a fantastic velvety tone by Titus Underwood.

Toward the end of the movement a light broke in through the woodwinds and all the gloomy gravitas that had rule the concert to this point emerged into a beautiful sunrise in the strings. Leave it to Tchaikovsky to create the perfect contrast to fate. This led to the sylvan (think Mendelsohn’s fairies) pizzicato third movement. Smiles could be seen across the orchestra and the sounds danced across the stage. Finally, the vigorous, forceful last movement, casting the gloomy fate motive aside, brought the evening to a triumphant end.

Other critics, even perhaps myself at a younger age, might criticize this kind of programming (a group of three famous chestnuts) as conservative and not engaging with contemporary expression. However, I disagree. First, the Nashville Symphony in my opinion, has done its share of contemporary programming and has numerous Grammy Awards to account for it. Second, one might criticize this music as irrelevant, important only to a lost culture, and disconnected from the politics of identity and our modern goals for diversity and inclusion. However, listening to these masterpieces by composers, not as “dead white men” but as humans with hidden and invisible illnesses, doubts and trials, a worthy story of resilience begins to emerge. As I looked around at the packed, seemingly sold-out hall, with nearly 2 thousand people of every age engaging in the standing ovation, I am sure that some were considering that, and I bet others weren’t. In the end, I believe that in artistic appreciation of the masterpiece we can be selfish, and draw what we wish…this is what makes it a masterpiece.

Over in North Carolina:

Kwamé Ryan leads the Charlotte Symphony

On Saturday, January 14th the Charlotte Symphony, led by guest conductor Kwamé Ryan, presented a wonderful performance of Aaron Copland’s Symphony No. 3, John Adams’ Short Ride in a Fast Machine, and Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s Concerto for Violin in D Major, Op. 32 with Bella Hristova on the violin. The evening was a marvelous exhibition of virtuosity and old school American patriotism exercised in fanfare.

Ryan started bravely with Adam’s virtuosic (especially for the conductor) Short Ride on a Fast Machine, which the composer once described as “You know how it is when someone asks you to ride in a terrific sports car, and then you wish you hadn’t?” Short Ride is a post-minimalist piece that adheres to minimalist techniques but places them in more dramatic settings, in this case a large and sophisticated orchestra. It begins with a couple of notes and rhythmic cells at a high tempo that are aggregated until they are subsumed in the timbral and texture of the piece. Sections are articulated as parts come in and fall out, changing the music’s “landscape.” Percussion is sine qua non, and Charlotte’s percussion section, led by Brice Burton, were on their game. Ryan maintained a nuanced balance across the sections–it is quite easy for the winds and brass to bury the strings, but Ryan ensured that all pistons were firing equally. It was exciting, optimistic and almost manically utopian. When it ended, I realized I had been holding my breath!

The challenge of Korngold’s Violin Concerto, the second work of the evening, is not technical mastery, although there is a great deal of that. It requires that the mastery be immersed in a fluent lyricism. Primarily a film composer, Korngold’s melodies and romantic style in films like The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and Juarez (1939) were ground breaking in their application of the highest expression of German Romantic Opera to the dramatic medium of film. A Hollywood composer and refugee of Nazi Austria, Korngold had given up composing concert music from 1939 until Hitler was defeated. His violin concerto was his first piece after his return and in the next decade he would only write concert music. Oddly enough, in a period where concert music was influencing the music of the screen, for Korngold it was just the opposite—his film music influenced his concert works.

Soloist Bella Hristova approached Korngold’s melodies in a fluent but aggressive way—graceful and swashbuckling at once. From the first melody of the opening movement, a lengthy, yearning, singing tone that ascends to the heavens, already in dialogue with the orchestra, Hristova’s violin leaped, bounded and danced. This was countered by the luscious slow 2nd movement Romanza. Here, Korngold’s genius for delicate instrumentation reigned, with the gentle cushioning and context provided by celeste and harp. Indeed, Andrea Mumm Trammell (Harp, principal) deserves special mention for her performance throughout the evening. The final movement, a kind of staccato gigue, allowed Hristova to let out all of the stops and Maestro Ryan kept just enough control of the band to let her shine. Words fail: It was simply a marvelous performance.

The delight was only increased when she returned to encore with a “Bulgarian Dance Tune” that was nearly as bravura as the concerto itself.

After intermission, Copland’s Third Symphony closed the evening. Rich in Copland’s nostalgic American sound, his Third Symphony was written at the end of the Second World War and inspired by Roosevelt’s four freedoms (of speech, of worship, from want, from fear). It culminates with a version of the Fanfare for the Common Man, that he had written earlier in 1942. Maestro Ryan gave a brief introduction in which he connected this work to contemporary events, specifically those in the Ukraine. I have always been uncomfortable with this political connection to the nostalgia in Copland’s sound. Political movements, especially autocratic movements, tend to emphasize a false nostalgia for the past in their calls for change and a reduction of human rights. It is certainly the case that Putin is employing a nostalgia for the glory days of the Soviet Union in justifying his invasion of Ukraine. Obviously Copland’s intentions had nothing to do with that, but, as they say, the author is dead. In anycase, Maestro Ryan gave a nuanced interpretation of Copland’s work, with its gentle imitative counterpoint, wide open registers and velvet diatonic dissonances. The stirring heroism and dignity of the final fanfare brought the audience to their feet.

In all, the concert was wonderful and the Charlotte Symphony put on a delightful program. I much prefer the sound in our Schermerhorn Symphony Center, the Belk was less alive and designed, it seems, more for opera. On entrance, with a reserved parking garage and a payment (only $10) in the venue system set up, I thought they had found a solution to parking, an issue that plagues us in music city. However, when we left, it took us no less that 50 minutes to get out of the parking garage. The search continues.

The Charlotte Symphony returns to the stage February 3rd and 4th with (former Nashville Associate Conductor) Vinay Parameswaran leading another innovative program of works by Smith, Britten, Still, and Sibelius.

Just in from Cleveland:

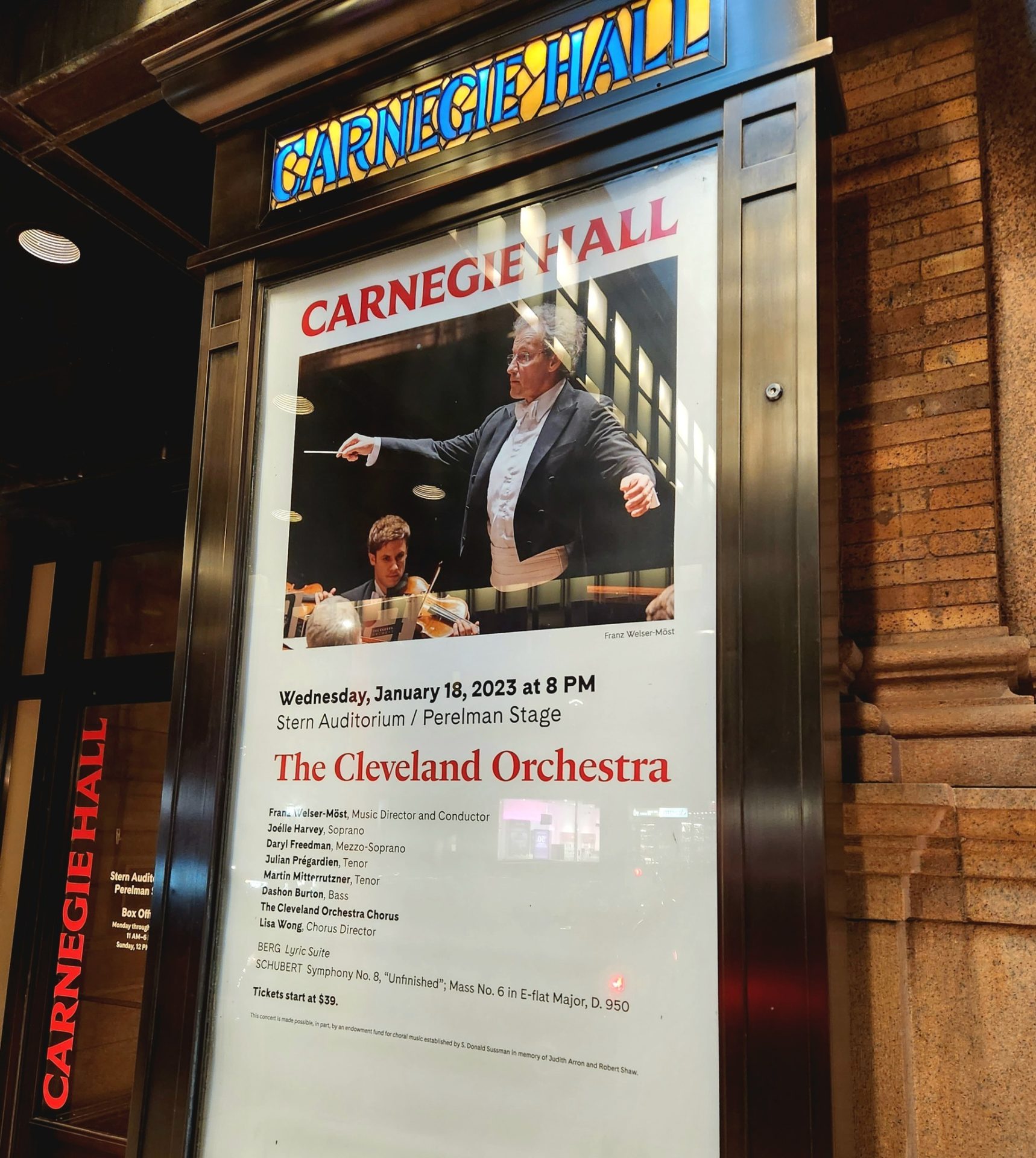

Welser-Möst Conducts Schubert – An Innovative Program by The Cleveland Orchestra

in·no·va·tion

/ˌinəˈvāSH(ə)n/

the action or process of innovating

“Innovation is crucial to the continuing success of any organization.”

Classical music organizations have received criticism for mostly presenting performances of pieces that have already become well-established in the canon of repertoire. Challenges have been made for such organizations to innovate. Calls demand for the curation of more diversified perspectives and experiences, including the championing for and commissioning of, new works that strive to receive more play than merely a premiere. It seems that The Cleveland Orchestra has responded to this charge – both with respect to programming, as well as the ways in which the institution connects with audiences.

Programming Innovations

During the winter and spring portions of The Cleveland Orchestra’s 2022-2023 season, perennial favorites are accompanied by various other works which are still establishing themselves within the regular cycle of repertoire. Sustain (2018) by Andrew Norman, Unsuk Chin’s SPIRA – Concerto for Orchestra (2019), and the world premiere of Wynton Marsalis’ new trumpet concerto written for principal trumpet, Michael Sachs, are examples that speak to this intention. Equally encouraging is the way in which established repertoire is paired and presented in a recent series of performances titled ‘Welser-Möst Conducts Schubert.’

Three performances of ‘Welser-Möst Conducts Schubert’ were offered for audiences in the Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mandel Concert Hall at Severance Music Center in Cleveland, Ohio, before the program traveled to New York City’s Carnegie Hall for one sold-out performance the following week.

The 1928 version for string orchestra of Alban Berg’s Three Pieces from Lyric Suite were combined with the two movements of Symphony No. 8 – “Unfinished” in B minor, D. 759 by Franz Schubert. The composite was offered in the following order and presented without applause between movements:

Alban Berg, “Andante amoroso” from Three Pieces from Lyric Suite

Franz Schubert, “Allegro moderato” from Symphony No. 8 – “Unfinished” in B minor, D. 759

Alban Berg, “Allegro misterioso – Trio estatico” from Three Pieces from Lyric Suite

Franz Schubert, “Andante con moto” from Symphony No. 8 – “Unfinished” in B minor, D. 759

Alban Berg, “Adagio appassionato” from Three Pieces from Lyric Suite

Breaks between selections were brief, only allowing a moment of silence before the next sonic landscape was offered. The first half of the program lasted roughly forty minutes. Late seating could only occur during intermission because of this reality.

Music Director Franz Welser-Möst offers that, “Alban Berg . . . is sort of the musical grandson of Franz Schubert. When you play them back-to-back, you can hear that they’re related – that what Schubert didn’t, or couldn’t, finish, Berg carried forward. It’s always rewarding to show where something comes from, where something goes to, and that music of different times is connected.”

Uniting ‘grandfather composer’ with his ‘grandson’ creates a listening environment that spans just over a century. While threads of similarities can be drawn between the writing of Berg and Schubert, it does require a larger-than-usual effort from the listener to absorb this cross-generational offering in real time.

Credit must be given to both players and conductor for executing Alban Berg’s “Andante amoroso” in such a manner that allowed for the movement to brilliantly evaporate into a moment of silence; a silence that was rather quickly proceded by the hauntingly beautiful melodic opening gestures of Franz Schubert’s “Allegro moderato” movement. Similar success was found in the transition between Schubert’s “Andante con moto” movement to the “Adagio appassionato” of Berg. While various bowing techniques, the density of gestures, and interplay between sections does have a scherzo-like quality, Alban Berg’s middle movement, “Allegro misterioso – Trio estatico,” left this listener feeling as though the evening’s repertoire experiment had inconclusive results. Perhaps additional listening and more score study could better prepare one for such an auditory amuse-bouche that shifts compositional styles.

After intermission the program concluded with Mass No. 6 in E-flat major, D. 950. Written in the last year of Schubert’s life, the premiere performance of this fifty-minute work was conducted by the composer’s brother just four months after Schubert had passed. Because of this, Welser-Möst speculates that perhaps there are elements of a requiem laced throughout the piece. Maestro Welser-Möst also offers in his program note for the work that Franz Schubert created a Mass form that was more pedestrian than a number of other composers: “Rather than express subservience to God, this music focuses on individual devotion, human emotion, and our own relationship with the divine.”

Lisa Wong, Director of Choruses, seems to have prepared The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus rather meticulously for this series of performances. While there were discrepancies with respect to the vertical alignment for a few consonants, the aesthetic achieved by this volunteer body was often mesmerizing and well-balanced throughout voice parts. Logistically, all members of The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus wore masks for the entirety of the performance. There were two specific instances in which Franz Welser-Möst demanded an immediate change in balance between vocal forces and instrumental contributions – the first in which woodwind soloists were encouraged to create sonic real estate and the latter in which the string consort was hushed from otherwise fully committing to the dynamic insinuations of the song-like topography. It is unclear whether this restraint in volume was the resultant of the masks creating an imbalance amongst forces or whether these requests from the podium were artistic decisions that intensified the music’s emotional output.

The “Credo” welcomed the first opportunity in which the program’s vocal soloists were featured. Tenor I, Julian Prégardien, and Tenor II, Martin Mitterrutzner, appeared to effortlessly match in tone and character of vibrato, working in tandem to maintain an ideal balance that, not so dissimilar to a kaleidoscope, created opportunities for each artist’s offering to shine in a coordinated effort. The penultimate movement –“Benedictus” – finally brings the composition to the vocal solo quartet. While the writing and the way in which it was performed was worth the wait, Schubert disappointingly composed with an economy that leaves one wanting more moments with the vocal quartet. Bravi tutti – Joélle Harvey, soprano; Daryl Freedman, mezzo-soprano; Julian Prégardien, tenor; Martin Mitterrutzner, tenor; Dashon Burton, bass-baritone.

Aside from the scandalous hidden messages that were composed into Three Pieces from Lyric Suite, mentioning nothing about the marital affairs that served as the impetus to do so, Alban Berg remains modern sounding even almost a century after having been written, suggest Hugh Macdonald and Eric Sellen, program note contributors for The Cleveland Orchestra. Because of this, an opportunity was missed to close the program with a current work, the vernacular of today, that would have allowed this program’s dialogue to traverse from the First Industrial Revolution with Schubert, to Post-World War I society and Berg, to a commentary about the twenty-first century. Perhaps future seasons might offer such a thought-provoking experience.

Organizational Innovations

Subsequent to live, in-person performances, The Cleveland Orchestra has developed initiatives to meet audiences through various digital media platforms. These innovations seem to provide more autonomy and speak to ways in which society currently consumes information and entertainment.

In October 2020, The Cleveland Orchestra began streaming performances, interviews, and behind-the-scenes content with the initiative, ‘In Focus’ on Adella Premium: https://www.clevelandorchestra.com/attend/seasons-and-series/in-focus/. The concert reviewed here was being recorded for a future release on this very platform. Memberships currently cost $14.99/month or $119.99/year.

‘On a Personal Note’ is a podcast that connects audiences with orchestra members, conductors, those with special affiliations to The Cleveland Orchestra, and guest artists: https://www.clevelandorchestra.com/podcast. Music Director Franz Welser-Möst speaks to his life-long relationship with the music of Franz Schubert on a recent episode. From childhood memories of his mother playing piano to a near life-threatening car accident while in college, Welser-Möst’s vulnerability informs one about his perspective – perhaps even providing a possible explanation for the two aforementioned instances in which Welser-Möst committed to moments of stillness and intimacy through dynamics in Schubert’s Mass.

Lastly, The Cleveland Orchestra has founded its own recording label. While not particularly innovative as a form of media, this reality is innovative from the vantage point of business savviness. No longer do arts administers need to succumb to the pressures of record executives and the legalities of contract language. Presumably now, The Cleveland Orchestra is free to record the repertoire it desires when deemed convenient for the organization. Let us hope that releases will also share in this spirit of continued innovation.

The MCR Interview

A Preview of Nashville Symphony’s ‘Modern Masterpieces for Brass’ with Tubist Gilbert Long

The Nashville Symphony will present ‘Modern Masterpieces for Brass’ at Schermerhorn Symphony Center on Wednesday, March 8, 6:00 p.m., as part of the Chamber Music Series. This free event will feature the following Nashville Symphony musicians:

Alec Blazek, trumpet

William Leathers, trumpet

Patrick Walle, horn

Paul Jenkins, trombone

Gilbert Long, tuba

Music City Review had the opportunity to connect with Gilbert Long about this upcoming performance. Mr. Long joined the Nashville Symphony in 1978. Long’s storied career as an orchestral musician, studio recording artist, and collegiate instructor, among other capacities, is balanced with his hobbies of golfing, motorcycling, and biking. Gil is married to Erin Long – a former violinist in the Nashville Symphony. The couple have two daughters, Hannah and Jessica.

Music City Review (MCR): The Nashville Symphony’s ‘Chamber Music Series’ is described as being, “. . . an informal and interactive concert-going experience.” What might attendees expect? Should shy introverts, like myself, be nervous?

Gilbert Long (GL): The ‘Modern Masterpieces for Brass’ concert is really just what one might expect of a normal concert, but with a relaxed environment. The musicians will talk about the pieces performed and brass chamber music in general. There can even be an opportunity for audience members to ask questions of the musicians during the concert.

MCR: Are you allowed and willing to share any of the works expected to be performed? The website states that the program is, “To be announced.”

GL: At this stage we are still working to finalize the program. Rehearsal time is difficult to find due to the ensemble musicians’ busy schedules. Soon we will read through potential repertoire and determine which pieces work well together, while also considering how much rehearsal time is available. We want to be able to provide a wide range of composers and styles to demonstrate a diverse sampling of brass literature. Of the modern music that we will read through, the following composers are being considered: Kenneth Amis, Jennifer Higdon, Eric Ewazen, and David Sampson.

MCR: How was repertoire chosen – and by whom? Are there similarities with the way in which repertoire is selected for the Nashville Symphony?

GL: Choosing music for the Nashville Symphony is completely different from the process used for this upcoming chamber concert.

For the Nashville Symphony, musicians are asked to submit repertoire suggestions to the Artistic Committee. The Artistic Committee is comprised of a combination of peer-elected musicians from the Nashville Symphony, staff members, and the Music Director. The Music Director ultimately organizes programs for the season.

Preparing the ‘Modern Masterpieces for Brass’ concert, all five musicians offer repertoire suggestions. Since each ensemble member has different chamber music experiences, this results in a more-varied list of potential repertoire than if only one ensemble member chose the program. We next attempt to secure the music – members already own some of the music suggested and sheet music needs to be found for other pieces. From there, reading rehearsals occur, where the group collectively decides which pieces should be programmed given the time restraints for subsequent rehearsals, as well as which repertoire pairings create an enjoyable program. In our situation, with so little time to rehearse, familiarity with the music helps speed-up the learning process.

MCR: Explain the rehearsal process for this chamber music program. How does the process relate to that utilized for a typical Nashville Symphony concert cycle?

GL: The rehearsal process is very different. The Nashville Symphony rehearses and performs repertoire within one week to ten days of a performance. The conductor leads the entire process. For this chamber music program all five musicians have a role in picking the program, deciding on a rehearsal schedule, and interpreting the music.

MCR: Describe the role that chamber music has played in your development as a student, professional musician, and educator.

GL: For me, chamber music is very important! In a large ensemble a conductor is responsible for a significant portion of deciding how the music is interpreted. In a chamber music setting, one is completely in control of one’s own contribution. Chamber music accelerates certain aspects of performance: how one interacts with other performers, the ability to adjust to what one hears, and the process of forming one’s own interpretations of the music. Performing in a chamber setting is important to the development of one’s personal style, character, and creativity. Each musician brings their talent and personality to the ensemble.

MCR: With respect to chamber ensembles, what advice do you have for aspiring musicians about performing in this medium?

GL: When I was younger there were very few original compositions written specifically for brass quintet. We mostly played arrangements; many were not even that good. Within the last forty years, there is now an amazingly large selection of arrangements and original compositions for this medium. Students should try playing a wide variety of music styles. Do not be intimidated by pieces that look too hard or ignore pieces that look too easy. I encourage aspiring musicians to learn what challenges them both musically and technically, and then seek out that type of repertoire.

MCR: Help us diversify our listening outside of classical music. What soundtrack is playing when you ride your motorcycle?

GL: In general, motorcycle riding is the great escape. It clears my mind. The helmet is kind of an isolation chamber for my brain. The soundtrack playing is my own thoughts. It’s cheaper than therapy!