Nuevo de Music City

Spanish American Culture 1500-1800: A Collaboration between Music City Baroque and the Frist

(Spanish Version Here: https://wp.me/pabEmc-2z1)

In collaboration with the Frist Art Museum, and paired with the museum’s current exhibition Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500-1800, the Music City Baroque is holding a concert at the museum on Saturday, January 13, 2024 titled Music and Musicians in Spanish Latin America, 1500-1800. The exhibition, which presents a mixed media collection of highlights from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s collection of Spanish colonial art, displays an amazing diversity of artists drawing from a broad range of traditions expressed in both sacred and secular art, pushing against the received monolithic conception of Spanish American art.

An excellent example of the collection’s wealth is Manuel de Arellano’s Virgin of Guadalupe (1691). The work is a meticulous 1691 copy of the original, an acheiropoietic image (not created by a human) of the virgin on a tilma (indigenous cape), which remains in Mexico City’s Basilica of Guadalupe where it is venerated as a relic of the virgin. This basilica is said to be the most-visited Catholic shrine in the world. According to the legend, and as depicted in the four corners of the painting, the Madonna appeared to Juan Diego three times so that he might convince the local Bishop to build her a chapel to the North of Mexico City. Her appearance on the tilma among rare flowers (depicted in the lower right in Arellano’s painting) is said to have ultimately convinced the Bishop. To the painting, which is a replica of the tilma, Arellanos added the inscription “touched to the original” (tocada a la original) to emphasize that the copy was authentic and shared a connection with the relic. Along with this beautiful work, the exhibition features a generous sample of paintings, sculptures and decorative arts for visitors to explore.

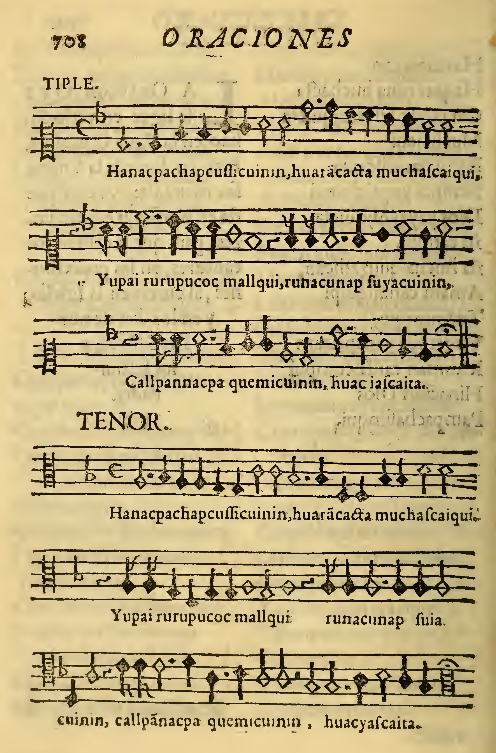

Similarly, according to an email from Board President Mareike Sattler, the Music City Baroque’s concert will present a variety of music from different regions” [of Spanish America] throughout the time period. A fine and related example of which is the 17th-century Quechua-hymn “Hanaq Pachap” from Peru. The hymn, a processional hymn to the Virgin Mary, likely written and composed by Franciscan priest Juan Pérez de Bocanegra in the Quechua language. As part of Bocanegra’s book Ritual formulario, the hymn is said to be the earliest work of vocal polyphony printed in the Western Hemisphere. Of the Hymn, Bocanegra said: “The Prayer that follows I did write in Sapphic verse, in the Quechua language, in honor of the Immaculate Virgin: the music is composed for four voices such that cantors may sing it for processions, upon entering into the church, and on days dedicated to our Lady, and on her feast days.” The lyrics to the hymn are carefully molded in order to maintain a syncretic balance—they might be interpreted in a way that accommodates both an orthodox Catholic belief even as they continue in the traditional Quechua culture.

Excerpt from Second Verse: “Attend to our pleas, O column of ivory, Mother of God! Beautiful iris, yellow and white, receive this song we offer you; come to our assistance, show us the Fruit of your womb.” (Quechua: “Uyarihuai muchascaita Diospa rampan Diospamaman Yurac tocto hamancaiman Yupascalla, collpascaita Huahuaiquiman suyuscaita Ricuchillai.)

Excerpt from Second Verse: “Attend to our pleas, O column of ivory, Mother of God! Beautiful iris, yellow and white, receive this song we offer you; come to our assistance, show us the Fruit of your womb.” (Quechua: “Uyarihuai muchascaita Diospa rampan Diospamaman Yurac tocto hamancaiman Yupascalla, collpascaita Huahuaiquiman suyuscaita Ricuchillai.)

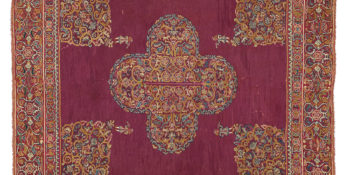

The hymn, with its homorhythmic construction, halting syncopation, vividly dramatic Marian lyrics and emphasis on native flowers, is considered to the aural equivalent of the Cuzco School of painting from the period in Peru. The Cuzco School drew a loose influence from the Flemish and Italian Renaissance, using bright colors of red, yellow and earth tones and lavish gold leaf in depictions of dramatic images. Although Arellano’s Virgin of Guadalupe is from the same period and carries some of these characteristics, its provenance is too far north to be of the Cuzco School.

One imagines that it will be in these broad cultural connections of belief, expression and cultural interaction that the exhibition and concert will find its greatest power. And, as Sattler relates, the concert promises a grand selection of works including music by Mexican born Mauel Zumaya, a fandango for Baroque guitar by Santiago de Murcia as well as “recently recovered pieces from the Jesuit missions in Bolivia” and others. While an exhibition that seeks to portray the art of several cultures across two continents through three centuries will, by necessity, be reductive and redundant, one must note, for the Music City, this collaboration between the Frist and Music City Baroque is sure to be a great start! The Concert is on Saturday, January 13th and the exhibition continues through January 28th in the Upper-Level Galleries of the Frist Museum.

This article is supported by a generous grant from

Funny Girl: Broadway at TPAC

Most of us know Funny Girl from the 1968 movie starring Barbra Streisand, who also starred in the original Broadway production of the musical. It’s a semi-autobiographical musical based on the life of Fanny Brice, who was a singer, actress, comedian, and radio personality. Framed as a flashback, the musical follows her journey from a star-struck teen who is told she isn’t pretty enough to succeed in show business, to getting her first roles, making her big break and falling in love. The second half of the musical focuses more on her life after professional success and her stormy relationship with a professional gambler. It’s a bittersweet comedy that emphasizes the humanity of its protagonist; it focuses more on its main character than on providing vicarious dream-fulfillment or success-bashing for the audience.

This Broadway revival is the first North American tour of the show since 1996, and features a slightly updated book by Harvey Fierstein. Katerina McCrimmon stars as Fanny Brice and is fantastic. She is funny, she can dance well and has great comedic timing. Most of all, her voice is superb, powerful enough to fill Andrew Jackson Hall, and with a wide range that is always in her control.

Another favorite on the stage is Izaiah Montaque Harris, who plays Eddie, Fanny’s friend and a choreographer who teaches her moves that help her get big. His tap dancing, which features notably several times, is the best I’ve seen in a live performance, and leaves me wondering why tap dancing has faded from much mainstream consciousness. There are many dance numbers, especially with the ensemble, and Ayodele Casel’s tap choreography was probably my favorite part of the production. A few times during the performance I could feel the vibrations of audience members tapping their feet.

The sets were well designed, and the costumes, designed by Susan Hilferty, were delightful. The lavish shows of Fanny’s time provide a great variety of costumes, including giant butterflies, flower headdresses, sparkle, and delightful period clothing.

With the classic 1960’s Broadway Sound, Funny Girl has melodies that stick in your head after the show. The funniest song is “His Love Makes Me Beautiful,” when Fanny Brice is early in her career and cast as a stunning bride in an opulent piece. She knows she doesn’t have the right stereotypical “beauty” look of the times for the song to be successful, so she adds one comic element to subvert the entire song from sentiment to hilarity. Here’s a link to a clip from the 1968 film:The Most Beautiful Bride | Funny Girl | Love Love. “You Are Woman, I Am Man,” is a funny song of seduction, although the love interest, Nick Arnstein (played with charming humor by Stephen Mark Lukas) is a bundle of red flags. The most notable song of the musical is “Don’t Rain on My Parade,” with its contagious energy and rebellious catchiness, which Katerina McCrimmon sings with defiant vigor.

One part of the musical hasn’t aged terribly well; the character Nick Arnstein is an weak, insecure man who is upset about having a wife more successful than him, and he is given much sympathetic attention in the second act. Luckily for us now, most of us consider that regressive and not an understandable issue of pride. Of course, contemporary attitudes don’t change the issues people struggled with 100 years ago, and this shortcoming of the play can’t overpower its quality and joyful spirit.

Any fan of the theatre will enjoy this musical. Its music, humor, and story are iconic and it’s a spectacle of dance and colorful costumes. It is a memorable and unique show with an odd hybrid nostalgia of watching a 2024 performance of a classic 1960’s musical presenting its impression of early 20th century Broadway.

Funny Girl is at TPAC January 2-7. For tickets and more information, see Funny Girl | Broadway Shows in Nashville at TPAC, and Funny Girl on Broadway

Musical Whirlwind: Fanfares, Waltzes, and the Irresistible Mambo Beat!

(Spanish version here: https://wp.me/pabEmc-2yI)

In the innate expression of the human condition, which came first, music or dance? The mystery in this question, where all answers can be legitimate, has been essential to the authenticity of artistic creation. Within classical music, dances have inspired small pieces such as Bach’s Partitas and Inventions, and have served as an articulating element in monumental symphonies such as Mahler’s 8th. This artistic conjunction reveals the nature of being: its need to gather in community and with its inner self.

The concept of “Symphonic Dances” arises from the nationalist projection that both Romantic and Modern composers employed to portray their roots and the contexts that shaped their musical essence. Within this distinctive style, the Nashville Philharmonic chose compositions by Leonard Bernstein and Sergei Rachmaninoff as part of the program performed on December 12th and 19th under the baton of Christopher Norton and Tal Benatar, at the Casa de Dios Church and Plaza Mariachi. The repertoire also featured Robert Schumann’s Konzertstück for Four Horns, with soloists Leslie Norton, Radu Rusu, Hunter Sholar, and Anna Spina -members of the Nashville Symphony- who skillfully weaved the wonderful timbral textures of this piece.

Immersed in this repertoire are memories, omens, eras, and races. Both Bernstein and Rachmaninoff reflect on the impact of immigration on American society, and the myriad of feelings that become entangled with the expectations of an outsider. The Symphonic Dances from West Side Story synthesizes the soundscape Bernstein composed for a Broadway musical into an orchestral suite. West Side Story transforms the conflict between the Capulet and Montague families in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet into the urban rivalry of the “Sharks” (Puerto Ricans) and “Jets” (Americans) gangs. Bernstein depicts this feud by alternating Cuban rhythms such as mambo and cha-cha-chá with swing and jazz. The orchestration of the suite preserves both the Latin percussion and the Big Band, creating a pleasing effect of dissociation between the orchestra families. Throughout the piece, the audience is exposed to a range of unexpected colors. In the first movement “Prologue”, the orchestra is muted highlighting the exquisite blending in the unison of the xylophone with the piano and the vibraphone with the harp.

Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances follows a similar thematic thread to Bernstein’s work. However, in this piece, the composer assumes the role of a present narrator. The composition consolidates Rachmaninoff’s musical journey in his native Russia, and in the nations that welcomed him when he had to escape the Revolution. The first movement takes off with a vehement march that extends at length into a motif composed of only three notes. Just as in Bernstein’s work, the saxophone prominently features among solo lines, acting as an emotional prelude to climactic sections. The second movement is a waltz that doesn’t hold back in bursting into harmonies and effects in the brass, without overshadowing the delicate melodies of the strings and woodwinds. The third movement blends the Russian Orthodox chant with the Dies Irae, hinting at Rachmaninoff’s farewell to the musical and earthly realm. This suspicion is confirmed at the end of his manuscript, where the words ‘I thank Thee, Lord’ can be read. However, this movement within its continuous alternation between serene and agitated changes in tempo, does not convey the anguish of approaching the end but rather the triumph of life over death.

In the “symphonic dances,” the role of the brass is pronounced given its sonority traditionally associated with ceremony and celebration. The Konzertstück for Four Horns upholds this conception by presenting the first movement in fanfare style. In addition to this, Schumann further explores the ritornello form to structure his innovative proposal of a multiple concerto. Likewise, the lines of each soloist are arranged in keeping with the characteristics of this period; the horns interact between duets and chorales with outstanding moments of virtuosity. The distribution of the melodies in the piece, both of the soloists and the orchestra, highlights another element in common with Bernstein and Rachmaninoff’s dances. The usual structure for a symphony orchestra work is altered by the intimate and vulnerable sound of chamber music. Multiple conversations between solos define episodes of introspection and transition within the festive orchestration of the dances. One such episode is evident in the sweet introduction of a viola-led string quartet in “Somewhere” from the Symphonic Dances of West Side Story. In the first movement of Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances, a similar lapse happens in the woodwind family, where the delicacy in the counterpoint of the voices makes this section a sublime moment.

As part of the Nashville Philharmonic’s initiatives, they actively seek new audiences in cultural, academic, and religious venues. Pursuing this mission, the orchestra has organized free concerts in 21 metropolitan districts of Nashville over the past 20 years. For this event, the chosen venues were within the city’s Latino community, and as a result, the repertoire featured the Symphonic Dances from West Side Story. At Casa de Dios, programs were thoughtfully distributed in Spanish, and the orchestra facilitated a connection between the conductors and the audience through a verbal translator.

Coming to TPAC

Funny Girl At TPAC!

Featuring one of the most iconic musical scores of all time, including classic songs “Don’t Rain On My Parade,” “I’m the Greatest Star,” and “People,” this bittersweet comedy is the story of the indomitable Fanny Brice, a girl from the Lower East Side who dreamed of a life on the stage. Set in New York City in the 1910’s, everyone told her she’d never be a star because she didn’t have the required looks, but then something funny happened—she became one of the most beloved performers in history.

bittersweet comedy is the story of the indomitable Fanny Brice, a girl from the Lower East Side who dreamed of a life on the stage. Set in New York City in the 1910’s, everyone told her she’d never be a star because she didn’t have the required looks, but then something funny happened—she became one of the most beloved performers in history.

This semi-biographical Broadway musical is familiar even to non-Broadway patrons through the 1968 film adaptation, which won Barbara Streisand an Oscar and Golden Globe. The updated book is from Harvey Fierstein based on the original classic by Isobel Lennart, tap choreography by Ayodele Casel, choreography by Ellenore Scott, and direction from Michael Mayer, this is a love letter to the theatre.

Performances are January 2-7 at TPAC’s Andrew Jackson Hall. For tickets, see Funny Girl | Broadway Shows in Nashville at TPAC.

For more information on the Funny Girl North American Tour: Funny Girl on Broadway.

At Play Dance Bar

Embracing a Queer Christmas: a review of Christmas Carol Circuit Party

A compelling parallel can be drawn between the era when Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol and Woven Theatre Company’s Christmas Carol Circuit Party. Already an internationally acclaimed literary celebrity and social critic, Dickens became involved in Victorian Britain’s efforts to re-evaluate past Christmas traditions so that they would better reflect the social struggles of the time as well as resonate with their contemporaries. Christmas Carol Circuit Party actualizes Dickens’ story to further challenge the traditions by suggesting a much-needed contemporary and inclusive contextualization, through the lens of the LGBTQ+ community. This production follows Woven Theater’s appreciated performances Initiative (2020) and The Naughty Tree (2022), and it stays true to its mission to give room to bold voices of underserved artists and produce daring new art.

And what better place to present the queering adaptation of A Christmas Carol then at Play Dance Bar, a venue already offering a space for drag sensationalism, feelgood freedom to express sexiness and sexuality as well as confront the identity binaries and heteronormativity.Especially considering the disturbing efforts to promote transphobia against transgender individuals and drag artists that took place during the year we’re leaving behind, it seems more important than ever to take space and expand, modify classical stories and blatantly insert in them the existence and thriving of a long-discriminated community.

The adaptation is vastly festive and celebratory – the audience is invited to the performance an hour early because what would normally be a theater foyer, in this case, is a club dancefloor. It’s the kind of setting you want to be in with friends, unless you’re the frivolous type to approach strangers and introduce yourself through the beats and rhythms of music driving your body to move. A few minutes before the doors open, Sunni and Shabaz Ujima, two very self-confident looking and spectacularly dressed actors/dancers take over the dance booths, setting the tone for what’s to come. It is impossible not to notice their agency because of how naturally they obtain themselves and move as if they were in their own bedroom, with no one around to gaze.

In the showroom, the mise en scène sets a cabaret atmosphere, with the long bar stretching in the back of the stage, booths, and round tables on the sides of the catwalk and plenty of room for those who have bought regular (standing) tickets to become immersed with the actors who utilize the majority of the space to perform. The laser lights take the place of Christmas trees, while leather, leopard skin, shiny fabric and latex designed by Iris Daniel and Dee Benn presage the kinky tone of the performance.

A queered motherly Dickens is put in the role of the narrator. A stylistic prodigy, charmingly announcing the scenes and connecting the passages between, this character brings laughter with their satirical and ‘drama queenie’ attitude. The bitter miser Ebenezer Scrooge on the other hand is actually the owner of the club, overworking his underpaid employees. He is stingy and ruthless. The portrayal of Scrooge’s labor abuse towards his poverty-stricken queer workers trying to make it through the day can be read as a reference to how our societies push those in the margins even deeper down the pit. “Poverty will teach you lessons you do not deserve”- says Dickens, rolling their flowery lace umbrella. Scrooge grudgingly gives his employee Bob Cratchit time off during Christmas Eve after he begs to be with his emotionally ill child Tiny Tim. Cratchit (same as all Scrooge’s employees) despises Scrooge, but he doesn’t have a choice but to obey just to make ends meet and be able to afford Tiny Tim’s medicine.

As in Dickens’ novel, Scrooge is visited by the ghost of his former business partner Jacob Marley, entwined in heavy chains dangling from his chest as punishment for his lifetime sins. Marley’s chains and costume add to the embracing of BDSM practices among the gay community, making the performance even more distinct. A pleasant twist is inserted in the plot by binding Scrooge and Marley as ex-lovers. As Marley warns Scrooge to change his attitude if he doesn’t want to end up burning in the fires of hell like himself, beautiful scenes of longing for a lost love unveil in front of our eyes.

The spirits of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come are none other than all-star local drag queens Nichole Ellington Dupree, Sapphire Mylan, and Venus Ann Serena, firing up the show atmosphere. The voguing scenes not only deconstruct the story but they also open space for the audience to take in and digest the multitude of emotions that the performance evokes. An interesting but seemingly common audience interaction occurs when many mainly male bodied audience members approach the dancefloor, offering mostly one-dollar bills to reward the drag queens. My expectation was that the divas would tear the money up, because rewarding their spectacle with money, especially with one-dollar bills, could also be considered as an offensive undervaluing of their skills and prestige. However, the receiving of money (in one case by even shoving it in the mouth) is also a reference to the struggles of drag queens to survive by practicing their art.

In terms of the storyline, although playwright River Timms stays quite loyal to Dickens’ novel, dramaturgically speaking, there are moments in the performance that stay rather loose. The insertion of the shibari roping piece for example is unrelated to the show as a whole, therefore it is hard to justify its aesthetically fitting and pleasing presence without any connection to the plotline, other than to consider it as a breather. Similarly, the three drag queen ghosts’ performances can be considered the highlight of the piece however their role as the ghost of the Past, The Present and Yet to Come remains vague, but hey, who doesn’t know the classical plot of A Christmas Carol anyway?

A refreshing addition to the performance that brought a heart-rending affect was the presence of poet Joshua Moore reciting their nostalgic verses live on stage.It took about 18 months for playwright River Timms and director William Kyle Odum to tighten up the sleek and shiny performance casting Dee Benn, Miles Gatrell, Blake Holliday, Jane, Jack Read, and Shabaz Ujima. The production is live scored by Aazera, with Sam Lowry on production design, Elizabeth Read on experience design, mask design by Jack Read, lighting design by Taylor Thomas, and choreography by Shabaz Ujima. The production is produced by Daniel Jones, Sam Lowry, William Kyle Odum, and River Timms. Although Christmas Carol Circuit Party specifically depicts Christmas, a holiday celebrated by a large population (not everyone!) at a very specific time of the year, due to the need for further queering of theater stages, it can and should expand to a repertoire beyond this time of the year.

The MCR Interview

Denice Hicks on Her Career and The Nashville Shakespeare Festival

As actress and administrator, Denice Hicks has been one of the most pivotal players in Nashville theater for several decades. This year she announced her imminent departure from the Nashville Shakespeare Festival to embark on her own creative projects. MCR Journalist Grace Tipton took the opportunity to interview Hicks on her career (so far) and work with the Nashville Shakespeare Festive.