The Cher Show at TPAC

On the freezing nights of January 19th and 20th, 2024, and despite its own frigid theater, TPAC managed to warm up Nashville with a delightful production of The Cher Show, a multi-Tony Award-winning jukebox musical detailing Cher’s long and remarkably prodigious career.

Generally, the problem with the jukebox musical is the narrative–how to string many songs (in this case over 25) into some kind of story for an evening that makes sense and isn’t forced. However, here it works quite well because Cher’s career, from Phil Spector to Moonlight, from early television to autotune, from Sonny Bono to Rob “Bagel Boy” Camilletti, is as diverse, if not more so, than her huge catalogue of songs. As is typical of musical biographies, her life is split into three stages—youth “Babe”, adult “Lady” and legacy “Star”, and the musical quite innovatively has these three stages appear as characters on stage.

Representing Cher in her youth (late teens through 20s) “Babe” Ella Perez performed quite well, balancing the young artist’s drive and idealism with her naiveté. Her duets with Sonny Bono (Lorenzo Pugliese) wonderfully expressed the sweet electricity and tension in their relationship (which you can still sense in the old youtube videos). As Cher the “Lady,” Catherine Ariale brought the confidence of Cher’s success, and made for a very relatable character in the face of her frustrations and setbacks. Morgan Scott’s “Star” embodied the woman in an amazing fashion. While all three sang in her incredible contralto range (the lowest female vocal range, overlapping a tenor), Scott’s diction was a magical interpretation of Cher’s singular, affected accent. She danced and walked with that lithe, paced gate and remarkable poise in nearly every ridiculous costume imaginable. And the costumes, oh the costumes!

They were sexy, flamboyant and as outrageous as Cher’s costumes were in real life. This is largely because the company hired Bob Mackie to design the costumes—Cher’s actual costume designer since the 60s. Further, Antoinette Dipietropolo’s sharp choreography contributed to an evening that, by the finale, had the audience dancing so exuberantly in their seats that security felt the need to come down the aisles and glare. The only real difficulty I found in the staging was Gregg Allman’s scene, which was a little more country western than he, his music, or his band ever were—it was more a New York Broadway clichéd 50s Nashville than 70s era Southern Rock from Atlanta.

Rick Elice’s book is also to be commended. Her three primary lovers caricatured in the musical, Sonny Bono, Greg Allman, and Rob Camilletti are not blamed so much as complicated. Her nostalgia for Sonny Bono and the moment she mentions his death is heartrending, even as there is frank discussion of their monetary disputes and silly comedy. Greg Allman (played by a suave Mike Bindeman) reflects his character’s notorious womanizing and flightiness even as it is contrasted with his love for her and their son. Camilletti’s (Charles Blaha) frustrated violence is contrasted with his loyalty. The depictions add up to a life and history of relationships that are balanced between the good and the bad, the nostalgia, fondness and regret. This is all to say that it feels, dare I say, authentic.

This certainly isn’t to say that there isn’t some historical revisioning happening. “Half-Breed,” Cher’s anthem to the native American population, is repositioned in the musical as her proclaiming her “half-breed” Armenian ancestry. It is hard to believe this given the existing video of her singing the song in native headdress, and the lyrics: “My father married a pure Cherokee.” This was a time when it was cool to claim Native American heritage, but it simply didn’t age nearly as well as she has.

In a related way, because so much of the musical is about her relationships, one gets the feeling that the musical wouldn’t pass any application of the Bechdel test. Even when she is alone with Lucielle Ball, the dialogue is about Sonny, and indirectly about Desi Arnaz. In a world dominated by men, Cher rose to stardom; it is this fact that makes her career so powerful and this musical so inspiring, even as it is entertaining, fun and glamourous. As a feminist call, her career too, perhaps hasn’t aged well, but as a story, it’s beautiful. The Cher Show’s run in Nashville is over, unfortunately, but if you don’t mind a bit of a drive, you can still catch it in Lexington, KY January 26-28th.

At the Frist

Music City Baroque Performs the Music of Spanish Latin America

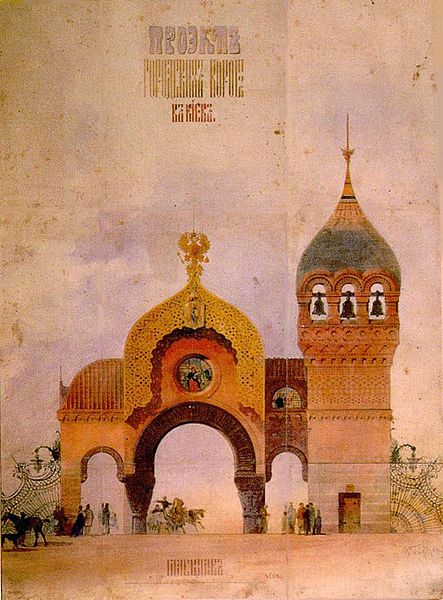

The exhibit Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500-1800 was curated by Ilona Katzew originally for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and is currently on display at the Frist Museum in Nashville until January 28th. Even more impressive than the scope of the exhibit’s theme is the range of types of objects on display. There are plenty of paintings to be sure, but colorful, beautiful bowls and screens and other artifacts demonstrate the practically global range of cultural influences on the arts in all domains, and especially the everyday, made by the people living in the Americas throughout the Spanish colonial period. This variety is more than impressive, however; it’s an integral part of the exhibit’s whole post-colonial perspective. The everyday objects on display help to fill in the gaps left by a largely Spanish bias in the records and histories of its colonies in the Americas, and they do so in a direct, vivid way. It’s one thing to try and get a sense for day-to-day life during the period through the journals of Jesuit missionaries or the records of colonial bureaucracies, but it’s quite another to see these incredible objects that might just as easily have been as lost to us as the memories of the very real people who made, handled, and used them. That they’ve survived into the present is the result often of luck, sure, but also the careful, diligent work of historical preservationists over the centuries.

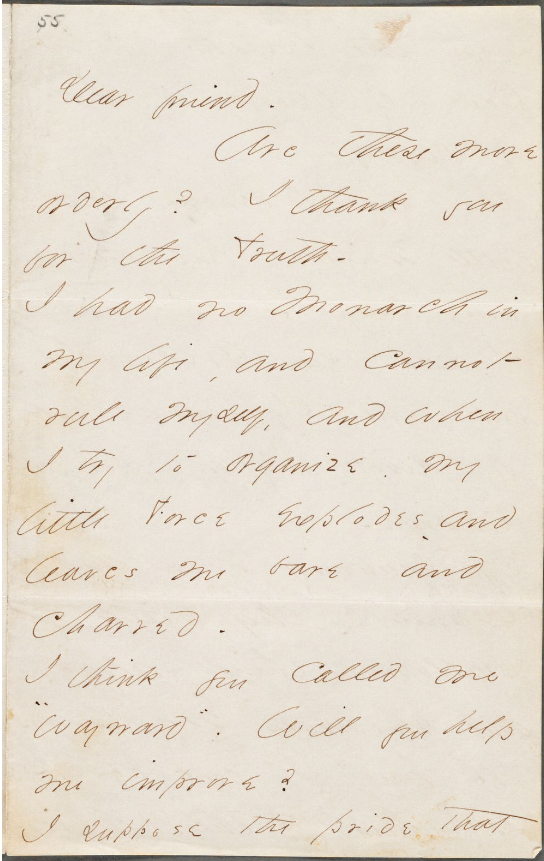

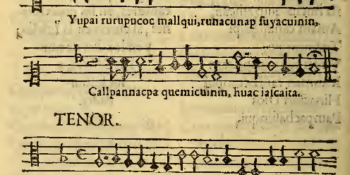

While overcoming colonial bias in our record of material culture is, then, obviously a challenge, it’s not one without a wealth of ways to work around. The same can hardly be said for what we can know about musicmaking during the same time. Most of what remains to us, especially in any form that can be readily performed, does so because it was written down in traditional European music notation, and probably for some type of Catholic liturgical purpose or perhaps as a part of a commercial enterprise. Even without considering the sheer volume of works that must have been notated in Spanish America during the period in question that simply have not survived at all, it’s clear that many of the specifics of contemporary performance practice will probably always remain somewhat unclear, to say nothing then of all the lost means, styles, and traditions of (especially popular and/or indigenous) musicmaking that would never have been written down or about in the first place. These are the challenges that Music City Baroque confronted in their musical analogue to the Frist’s exhibit, Music and Musicians in Spanish Latin America, last Saturday afternoon.

Despite the built-in difficulty of finding a suitable musical equivalent to something like household pottery for all the reasons outlined above and more, Music City Baroque President Mareike Sattler and Artistic Director Maria Romero Ramos nevertheless managed to provide an interesting if all-too brief glimpse into the musical life of the time. For example, the program’s opening piece was a Marian hymn in the Quechuan language by the Franciscan parish priest living in Lima, Peru, Juan Pérez Bocanegra, which, according to the program notes, represents “the first printed piece of polyphony in the Americas.”

This was followed by a setting of Beatus vir by Domenico Zipoli, a composer and Jesuit priest working in Paraguay. Zipoli’s Beauts Vir comprised the majority of the first half of the concert, and alongside the concluding trio of villancicos (a semi-liturgical, quasi-popular genre of sacred music described jokingly by Sattler as “proto praise and worship music”) saw Music City Baroque as an ensemble at their best. Guest performer and guitarist Dušan Balarin, also performed a solo fandango by the eighteenth-century Spanish composer Santiago da Murcia, whose published scores circulated in the Americas. Given the multicultural roots of fandango as a genre—with its origins in African and Spanish traditions in the Caribbean, but also as a cultural export back to Spain and the rest of Europe—da Murcia’s piece comes perhaps the closest to one of the core themes of the Frist’s art exhibit, namely that of “the generative power of Spanish America and its central position as a global crossroads.”

However, I think it’s the two instrumental pieces that followed the Zipoli Beatus vir that really allowed us to get a sense for the musicmaking of indigenous musicians during the period. Las Folias and Pastoreta Ypeche Flauta, performed here by two violins and solo recorder respectively, are anonymous, but were apparently part of a larger body of notated music recovered from a Jesuit mission, roughly a third of which was written by or for local musicians. I get the sense Music City Baroque were looking to prioritize breadth over depth of repertoire, which makes a certain amount of sense given the scope of the exhibit, but I would have liked to have heard more music from these anonymous composers.

In any case, it was during this middle portion of the concert that a minor disaster struck. It was hard to tell exactly what happened, but at some point during the performance of Las Folias, Maria Romero Ramos suddenly had to stop to retune a string or two. “That’s catgut for you,” she quipped to a laughing, forgiving audience. As she sought to get the strings back in order, the bridge (and maybe a tuning peg? Like I said, it was hard to tell from where I was seated) suddenly flew off the instrument entirely. Despite this being the kind of technical difficulty you don’t really expect to have to prepare for, Ramos was quick on her feet, and demonstrated the depth of her own professionalism and of the ensemble as a whole by pointing suddenly to Jessica Dunnavant to talk about her recorder and the upcoming Pastoreta Ypeche Flauta, which she delivered without so much as blinking as Ramos retreated offstage to see to her broken instrument (“Is there a violin in the house?” was met with more laughter).

For all my earlier talk about the Frist exhibit’s ability to evoke the everyday lives of the people of the past, Ramos’ faulty catgut strings or Dunnavant’s explanation of the expressive limitations of the period recorder she performed on served for me as interesting reminders of the limitations of thinking about this kind of exhibit/concert as some kind of virtual, imaginary “time machine.” Rather than understanding this experience as a process of transforming our understanding of the past by “traveling” to it, it’s worth remembering that these sounds and words, just like the bowls and paintings upstairs, have traveled forward in time and across wide stretches of space to us and are themselves changed in the process—an imperfect process overseen by institutions with plenty of failures of their own. Of course, catgut strings snapping or out-of-tune recorders are always a possibility in the historically-informed performance of a work by J.S. Bach or Claudio Monteverdi as well, but in the context of a concert dedicated in large part to the gaps and holes in our record of the musical past, of our ultimate inability to truly play it and hear it as it must have been, these sudden reminders of the materiality and lived-in nature of the musical traditions on display somehow felt appropriate.

Nuevo de Music City

La entrevista de MCR: Elizabeth Caballero y César Delgado hablan de ‘Florencia en la Amazonas’

La ópera de Nashville nos trae nuevamente una magnífica producción de la ópera Florencia en el Amazonas del compositor mexicano Daniel Catán. La obra se presentará los días 26, 27 y 28 de enero en el teatro James K. Polk. Esta es una ópera que nos su emerge en un viaje cautivador por el exuberante Amazonas junto con una historia realmente envolvente. Nos tenemos el honor de contar con la presencia de la soprano Elizabeth Caballero quien interpreta el papel de Florencia y también el tenor César Delgado encargado de dar la vida a Arcadio. Estos dos artistas nos compartán sus experiencias perspectivas sobre la obra y así como su participación en este emocionante proyecto. (Note: English Subtitles available)

The Cher Show at TPAC This Weekend

The Cher Show is a multi-Tony Award-winning jukebox musical which features 35 of her hit songs and tells her life story. Covering such a lengthy career calls for more than one woman and takes three women to play her: the kid starting out, the glam pop star, and the icon. These different versions of herself interact with each other as her story is told. The musical covers the ups and downs of her career, from when she and Sonny were “broke-ass broke,” to when Cher’s mother tells her to marry a rich man and she answers, “Mom, I am a rich man.”

In a pop-music landscape of rapid change and one-hit wonders, this EGOT-winning superstar is the only solo artist to have a number-one single on a Billboard chart for seven consecutive decades, and has a separate Wikipedia entry listing her awards and nominations.

After its premiere on Broadway in 2018 and a national tour delayed by COVID-19, The Cher Show is making its tour with Bob Mackie again in charge of the show’s Tony Award-winning costumes.

To see Cher interviewed with some of the original Broadway cast, see Jimmy Fallon’s interview with them in 2019: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kVt40fhq6E8. Coming to TPAC this weekend only, The Cher Show will be performed January 19-20, with two evening shows and a matinee. For tickets see The Cher Show | Broadway Shows in Nashville at TPAC and for more information about the national tour, see The Cher Show.

The MCR Interview

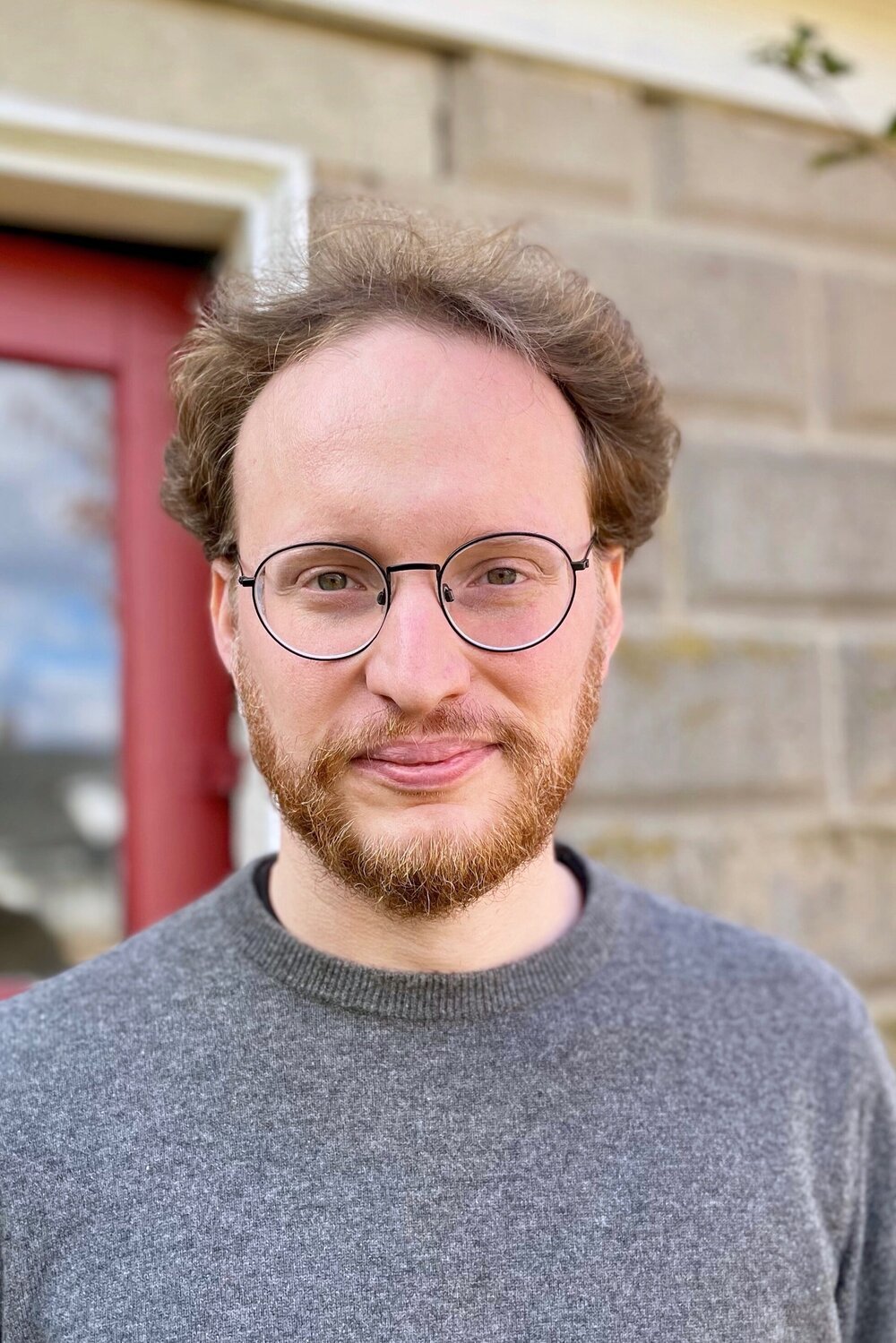

Peter Otto, the New Concertmaster of the Nashville Symphony

After a wealth of experience in the role elsewhere, Peter Otto has joined the Nashville Symphony as Concertmaster. The Music City Review journalist Carly Brown took the opportunity to ask him a few questions about his career, the position, and on a “lightning round” of perspectives.

Nuevo de Music City

Cultura hispanoamericana 1500-1800: una colaboración entre la Music City Baroque y la Frist

(English Version Here: https://wp.me/pabEmc-2yB)

En colaboración con el Frist Art Museum, y junto con la exposición actual del museo Arte e Imaginación en la América Española, 1500-1800, the Music City Baroque llevará a cabo un concierto en el museo el sábado 13 de enero de 2024 titulado Música y Músicos en la Latinoamérica Española, 1500-1800.La exposición, que presenta un compendio de medios mixtos de lo más destacado de la colección de arte colonial español del Museo de Arte del Condado de Los Ángeles, muestra una asombrosa diversidad de artistas que se basan en una amplia gama de tradiciones expresadas tanto en el arte sagrado como en el secular, contrastando la tradición recibida de la concepción monolítica del arte hispanoamericano.

Un excelente ejemplo de la riqueza de la colección es La Virgen de Guadalupe (1691) de Manuel de Arellano. La obra es una copia minuciosa de la original, una imagen aquiropoeta (que no es creado por un humano) de la Virgen sobre una tilma, que permanece en la Basílica de Guadalupe de la Ciudad de México, donde se venera como reliquia de la Virgen. Se dice que esta basílica es el santuario católico más visitado del mundo. Según la leyenda, y como se representa en las cuatro esquinas del cuadro, la Virgen se apareció a Juan Diego tres veces para que convenciera al obispo local de que le construyera una capilla al norte de la Ciudad de México. Se dice que su aparición en la tilma entre flores exóticas (como se representa en la parte inferior derecha del cuadro de Arellano) finalmente convenció al obispo. Al cuadro, Arellanos añadió la inscripción “tocada a la original” para enfatizar que la copia era auténtica y compartía una conexión con la reliquia. Junto con esta hermosa obra, la exposición presenta una generosa muestra de pinturas, esculturas y artes decorativas para que los visitantes puedan explorar.

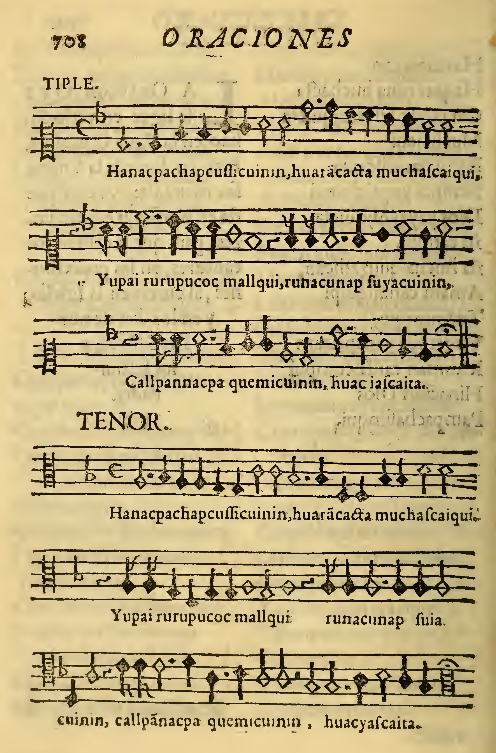

De manera similar, según un correo electrónico de la presidenta de la junta directiva, Mareike Sattler, el concierto de Music City Baroque presentará una variedad de música de diferentes regiones” [de Hispanoamérica] durante este período. Un buen ejemplo en relación es el himno quechua del siglo XVII “Hanaq Pachap” del Perú. Este himno procesional a la Virgen María, fue probablemente escrito y compuesto por el sacerdote franciscano Juan Pérez de Bocanegra en lengua quechua. Como parte del libro Ritual Formulario de Bocanegra, se dice que el himno es la primera obra de polifonía vocal impresa en el hemisferio occidental. Sobre el Himno, Bocanegra menciona: “es una oración en verso sáfico, en la lengua quechua, hecha en loor de la Virgen sin mancilla: y va compuesta en música a cuatro voces, para que la canten los cantores en las procesiones, al entrar en la iglesia, y en los días de Nuestra Señora, y sus festividades”. La letra del himno está cuidadosamente moldeada para mantener un equilibrio sincrético; puede interpretarse de una manera que se adapte a una creencia católica ortodoxa y que aún así continúe en la cultura tradicional Quechua.

Extracto del Segundo Estrofa: “¡Atiende nuestras súplicas, oh columna de marfil, Madre de Dios! Hermoso iris, amarillo y blanco, recibe esta canción que te ofrecemos; ven en nuestro auxilio, muéstranos el fruto de tu vientre”. (Quechua: “Uyarihuai muchascaita Diospa rampan Diospamaman Yurac tocto hamancaiman Yupascalla, collpascaita Huahuaiquiman suyuscaita Ricuchillai.)

El himno, con su construcción homorítmica, síncopa vacilante, letras marianas vívidamente dramáticas y el énfasis en las flores nativas, se considera el equivalente auditivo de la época de la Escuela de pintura de Cuzco en Perú. La Escuela de Cuzco obtuvo una ligera influencia del Renacimiento flamenco e italiano, utilizando colores brillantes como el rojo y el amarillo, así como tonos tierra y abundantes láminas de oro para representar imágenes dramáticas. Aunque la Virgen de Guadalupe de Arellano es del mismo período y tiene algunas de estas características, su procedencia está demasiado al norte para pertenecer a la Escuela Cuzqueña.

Uno imagina que será en estas amplias conexiones culturales de creencias, expresión e interacción cultural donde la exhibición y el concierto encontrarán su mayor poder. Y, como relata Sattler, el concierto promete una gran selección de obras que incluyen música del mexicano Mauel Zumaya, un fandango para guitarra barroca de Santiago de Murcia, así como “piezas recientemente recuperadas de las misiones jesuitas en Bolivia” entre otras. Esta es una exposición que intenta representar el arte de varias culturas en dos continentes a lo largo de tres siglos, sin embargo, será inevitablemente reduccionista. Es crucial señalar que, para la Ciudad de la Música, esta colaboración entre The Frist y Music City Baroque marca un gran comienzo. El concierto se presentará el sábado 13 de enero y la exposición continuará hasta el 28 de enero en las galerías del nivel superior del Museo Frist.

Este artículo fue apoyado por una generosa subvención de