From the Nashville Symphony

Clyne, Prokofiev and Mozart with Aspinall and Carissa at the Schermerhorn

On February 2 & 3, 2024 the Nashville Symphony performed their annual Lawrence S. Levine Memorial Concert which features the performance of an emerging artist. The program featured Anna Clyne’s This Midnight Hour, Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5 in B-flat major, Op. 100 and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 17 in G major, K. 453 with Janice Carissa at piano as the emerging artist. At the podium was Nashville’s Associate Conductor Nathan Aspinall. The evening was resplendent with wonderful new sounds and amazing interpretations of the old—something we are accustomed to at the Schermerhorn.

Clyne’s work, a stunning symphonic poem inspired by both Juan Ramón Jiménez’ poem La musica and Charles Baudelaire’s Fleurs du Mal, was remarkable for its excitement as well as the many different timbres Clyne scored and Aspinall was able to charm from the ensemble. The opening, which Clyne has stated, was “…inspired by the character and power of the lower strings of L’Orchestre national d’Île de France” is a tempest reminiscent of Richard Wagner’s great prelude to Die Walküre, but perhaps faster and with more intensity.

The tension was heightened even more so, a couple of minutes in, where Clyne paired the depth of the strings with bowed crotales (antique bells) and a piercing, yet piano piccolo—creating a kind of menacing bi-phonic timbre at either end of the aural periphery, centered by focused woodwinds. The café scene, played so well by the violas, felt like an outtake from Wozzeck; it was brilliantly written and played, as were the doppleresque horns. Across the lyrical sections, the timpani, and percussion more generally, served first as a reminder, and ultimately as a final intrusive statement, regarding the work’s direction. A wonderful opening piece performed with zest and fury.

Mozart’s 17th Concerto was written in the spring of 1784. Its opening movement is rife with the high Viennese utopianism that characterizes the period, exemplified in its primary theme, which is laiden with light turns and an accompanying alberti bass. Carissa tackled the movement with aplomb, if perhaps her interpretation was a little closer to Weber than Mozart. Indeed, while her emphasis of the early 19th century over the late 18th led to a consistent and darling interpretation that “worked,” in the Andante, the second movement, the approach was inspired.

In his biography of Mozart, Musicologist Maynard Solomon remarked that the Andante’s opening is “transient,” a “…brief moment of surpassing beauty, whose implications are premature and whose full meaning cannot be grasped until it has been repeatedly lost, forgotten, submerged, and then remembered.” In her opening and continued performance of this brief moment, Carissa’s deft creation of a gentle melodic nostalgia brought the lie to Solomon’s allegation. The movement’s later, and somewhat latent, thematic references, in her hands, enriched the movement’s beauty. In the finale she returned to the bright Viennese style, playing its wonderful, starling-inspired theme beautifully, but the Andante lurked in my mind. It was a masterful performance that earned the ovation. For an encore, she performed one of Enrique Granados’ Goyescas, and one could sense her comfort having returned to the literature from the 19th century. She is an amazing artist and we simply must have her back! In the meantime, during intermission, I slipped out for a whiskey and a breath of fresh air on the Schermerhorn’s patio. Birds, Broadway, whatever, I hope the symphony never changes location.

After intermission, we returned for Prokofiev’s masterpiece, which he wrote in 1944, at the height of the second world war. He described the work as “a hymn to free and happy man, to his mighty powers, his pure and noble spirit.” As such it is a distinctly heroic work of an epic nature. Indeed, the performance of the first movement was so arousing that it drew several exclamations of “Woo!” from the audience (Music City’s version of “Huzzah!”) and Aspinal blushed before he leaned into the manic velocity of the second movement. The central section, a brief reedy, woodwind song, only a transition, was performed with such a lovely delicate balance that it gave me chills. The meditative third movement, , with its soaring lyrical melody and violent outbursts played a wonderful antagonist to the victorious finale. By the end I was nearly as fatigued as the violin section and as I happily walked across the pedestrian bridge, I looked over at the patrons in the “Florida-Georgia Line” honky-tonk and thought to myself, “how in the world could their night’s entertainment even remotely compare to this?” Next, the symphony has a number of community events, a Romantic St. Valentine’s Concert, an artist spotlight (Stewart Goodyear) and a concert in the Chamber Music Series (Brahms Piano Quartet).

From the Nashville Repertory Theater

Indecent, Immoral, and Impure, Oh My! Nashville Repertory Theatre Presents Indecent

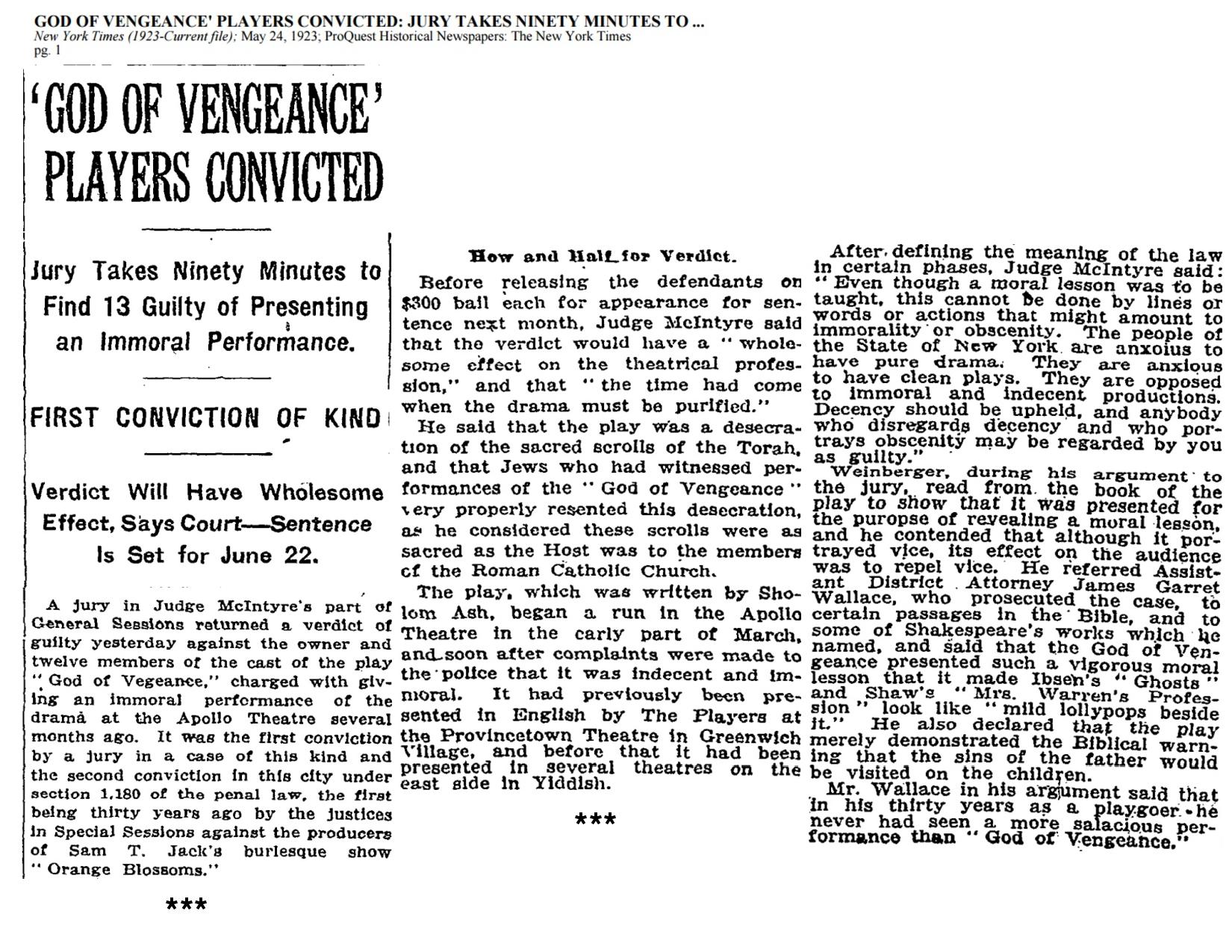

Friday, February 2nd was the opening night of Nashville Repertory Theatre’s production of Indecent. Written by Paula Vogel, Indecent originally opened at the Court Theatre on Broadway in 2017. It tells the story of Sholem Asch’s play God of Vengeance, starting with its creation, following as it is performed in multiple European countries before coming to Broadway, and ending with Asch forbidding any future performances. Throughout this story are the themes of censorship, intolerance, the horror of the holocaust, and the enduring nature of art.

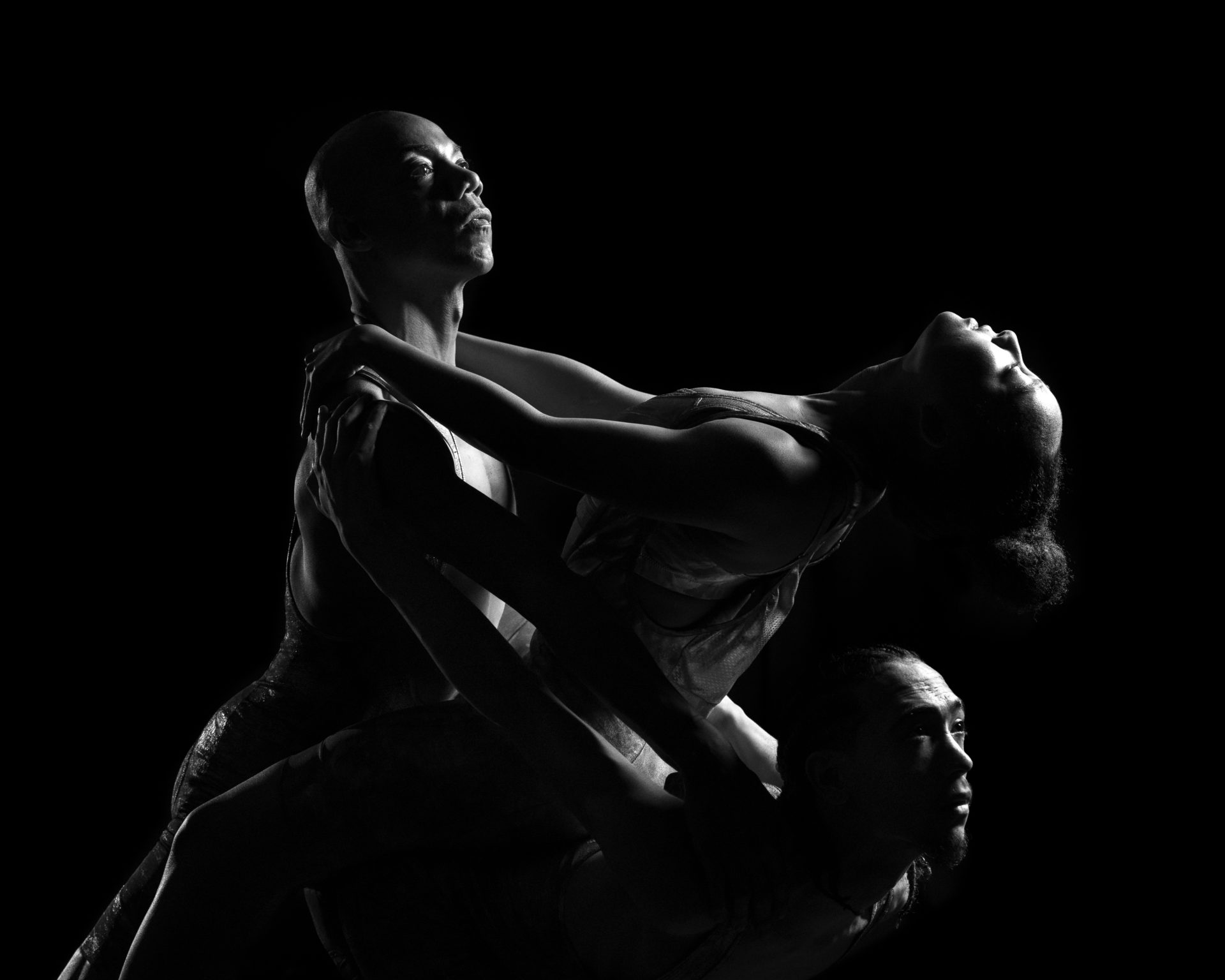

In 1907, Sholem Asch read his play, Got fun Nekome (God of Vengeance) to the founding father of modern Yiddish literature, I. L. Peretz. God of Vengeance tells story of a man who owns and lives above a brothel. He commissions the writing of a Torah scroll and wishes for his virgin daughter, Rifkele, to be a virtuous maiden so he can find her a respectable, Jewish husband. Instead, Rifkele falls in love with another woman: a prostitute named Manke. At the end, her father, enraged, tells Rifkele that she can pay him back for the Torah scroll by working at the brothel with Manke, and he throws the Torah across the room. Peretz was upset that Asch would write a play that portrays Jewish people in a negative way. He advised Asch to burn it. This interaction is one of the first scenes in Indecent and introduces us to one of the play’s main themes: censorship. Asch doesn’t follow Peretz’ advice and the play is very successful in Europe. When it finally reaches America, some people are unhappy with the subject matter. God of Vengeance is credited with presenting the first lesbian kiss on Broadway in 1923 at the Apollo Theatre on West 42nd Street. Along with translating the script to English, a beautiful scene with Rifkele and Manke dancing in the rain and falling in love is cut from the play to make it more “palatable” for the audience. Still, midway through one performance, a police detective informed the cast and producer that they were under arrest for obscenity. They went on trial and were found guilty, although the verdict was later overturned on appeal. The official violation of the penal code, The Court of New York is: “obscene, indecent, immoral and impure material.” Emphasizing another theme of Indecent: intolerance, Vogel places the actors that play Rifkele and Manke (Reina and Deine) also in a romantic relationship. At one point, broken-hearted, Deine cries onstage at the removal of the rain scene, changing the relationship in God of Vengance from one of passion and love to one of manipulation. She says “Now instead of us falling in love in this obscenity of a world, instead of me trying to rescue you-the new script has me entrapping you into a life of white slavery! I’ve been promoted to Head Pimp!”

Asch’s character is so traumatized by what he has seen in the aftermath of WWI (he is seeing the persecution of the Jewish people and the beginning of WWII) that he is in a state of deep depression and is unable to go to court to testify for the troupe. Lemml, the stage manager for Got fun Nekome, both in Europe and America, is heartbroken by his lack of support and goes back to Europe. He continues to put on the play back home because he believes in it so fervently. He is still putting on the play in a little attic in the Łódź Ghetto when they are all arrested and taken to a concentration camp. In a heartbreaking scene, we see the main characters in line for the gas chamber, Lemml imagines that the fictional characters Rifkele and Manke escape from the Nazi’s and run away together. At the end of the play, Asch is now an old man and is packing up to leave America because he is being persecuted by the House Unamerican Activities Committee. A young theatre student comes to ask him to look at his new English translation of Got fun Nekome. Asch refuses to look at it and states that he never wishes the play to be done again and echoes Pretez, telling the student to burn it. The student vows that he will one day produce the play. The last scene is the famous rain scene performed in Yiddish: Rifkele and Manke spin and dance in the rain, embracing each other.

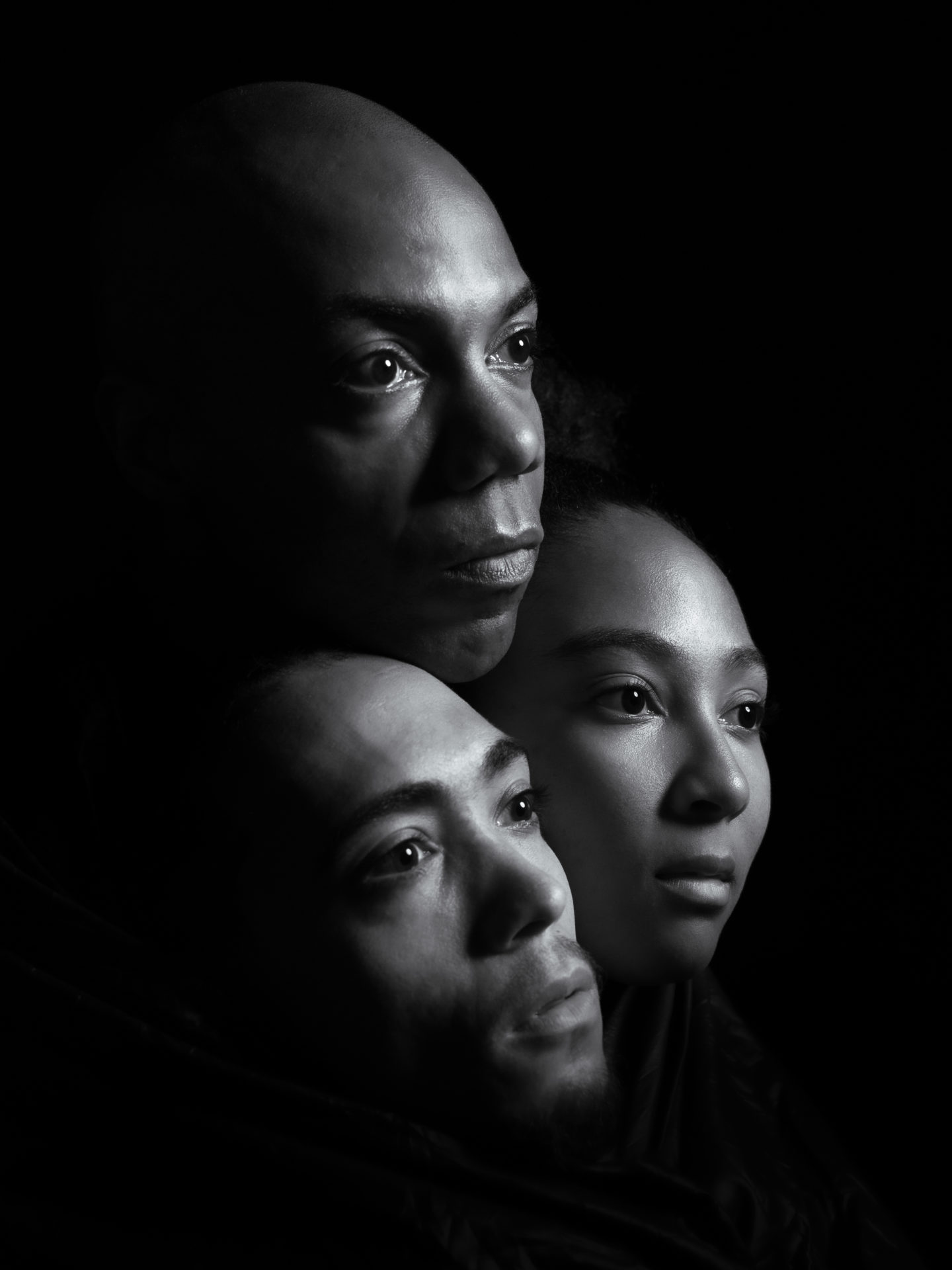

Indecent runs about an hour and 45 minutes without an intermission and has a small main cast of seven actors and 3 musicians (a klezmer ensemble of clarinet, violin, and accordion). This means that every cast member played multiple roles and never really had any time off stage. It is a testament to the actors that it was never confusing, and it was always clear who they were playing. Some of the success must also be attributed to Heather McDevitt Barton, the costume designer. She made every character believable by adding small props or items of clothing to distinguish from one character to another (or from one time period to another). For example, by the end of play, when the troupe is performing Got fun Nekome in an attic in the ghetto the actors have put on threadbare coats to signify how poor, tired, and hungry they are.

The characters in Indecent also occasionally spoke or sang in Yiddish. Once their characters make their way to America, they speak in halting English, to show that they are struggling with the language. Deine says at one point, “Lou, in my head, I can hear those English words so good, but then when I open my mouth, it’s like the dust of Poland is in my throat.”

Thomas Demarcus stood out playing the lovably innocent and naive Lemml. He was so earnest in his passion for the play and for the theatre, and for Asch himself that it made it all the more heartbreaking when Asch doesn’t come testify for them in court. Sarah Aili and Delaney Amatrudo did a wonderful job as Deine and Reina playing Manke and Rifkele. The love between them, passionate as Manke and Rifkele, and enduring and steady as Dine and Reina was so true and pure. They sing “Weigala” together in stunning harmony in the scene at the gas chamber. In the script it says, “We have come to our Kaddish. “Wiegala” was written by Ilse Weber, a nurse at the Childrens Hospital at Theresienstadt. She sang this lullaby for the children in the wards. When it came time for the children to be transported to Auschwitz, Ilse volunteered to go with them. It is said she sang this song in line to the chambers: ‘The wind plays on the lyre, the nightingale sings, the moon is a lantern… sleep, my little child, sleep.’” Although the audience is not told this, and it is sung in Yiddish, the meaning of the song is beyond words, the feeling unmistakably clear in their haunting rendition. The ending of the play, as they perform in Yiddish as Rifkele and Manke under the rain, was poignant, almost painfully beautiful, showing the audience the enduring nature of art, and the ability of art to sustain us through even the worst of times.

It made me laugh, it made me cry, Nashville Repertory Theatre’s production of Indecent is amazing. In the executive director’s note, Drew Ogle says “you are seeing the only professional production of this play in the country right now.” You still have time to see it. Go now! https://www.tpac.org/event/2024-02-02-to-2024-02-11-indecent/

Girl From the North Country: the Bob Dylan Jukebox Musical

In the Broadway musical Girl from the North Country, joy and sorrow are felt collectively, and they transcend temporal limits. Irish playwright and director Conor McPherson joins forces with composer Simon Hale, whose orchestrations for the musical were rewarded with a Tony Award in 2022. Set in Duluth, Minnesota in 1934, the play invites the audience to a musical journey that unveils the wretched destinies of individuals and families impacted by the Great Depression while they are temporarily floating at a guesthouse which is about to be foreclosed on.

More than 20 of Bob Dylan’s narrative-driven folk compositions are interpreted by a multi-racial cast in a storyline that, among other social matters, hazily depicts the racial issues of the time. Set seven years before Bob Dylan was born in Duluth, the playwright builds a connection between Dylan’s songs and the world in the musical. Dylan lived in Duluth only until he was six years old and left Minnesota in his early twenties to relocate to New York City, but he kept recalling his home state and dedicating songs to it, including “Girl from the North Country,” from which the musical takes its name.

More than 20 of Bob Dylan’s narrative-driven folk compositions are interpreted by a multi-racial cast in a storyline that, among other social matters, hazily depicts the racial issues of the time. Set seven years before Bob Dylan was born in Duluth, the playwright builds a connection between Dylan’s songs and the world in the musical. Dylan lived in Duluth only until he was six years old and left Minnesota in his early twenties to relocate to New York City, but he kept recalling his home state and dedicating songs to it, including “Girl from the North Country,” from which the musical takes its name.

Resorting to Dylan’s music, which is written a few decades after the time-setting of this musical, reminds me of the time-consciousness philosophy of the German phenomenologist Edmund Husserl. It centers on the idea of an extended or ‘living’ present, which involves not only the momentary now, but it extends into the past and into the future. How often do we neglect to acknowledge the extension to which the fates of our predecessors determine our lives and how our decisions will condition the lives of those to come after?

In the play we’re introduced to characters who briefly meet and intertwine their fates at the guesthouse owned by the Laine’s. There’s the inept Nick who manages the guesthouse and his wife Elizabeth, who’s attached to her box of money and purse, and is said to suffer from mental illness, although what we witness is an individual with a strong ability to speak the truth when others withdraw from saying it out loud. Their son Gene, a wannabe writer who squanders his life by drinking and loses his beau, and their adopted daughter Marianne who is impregnated by a mysterious man-shaped creature visiting her room one night, resembling her suitor Mr. Perry – or at least that’s what she elucidates. Nick’s lover, Mrs. Nielsen, awaits her late husband’s shares on the railway construction to be able to run away with him. There’s also Dr. Walker who serves as the narrator of the plot as well as Elizabeth’s doctor, making sure she as well as other guests are equipped with their drug of choice. Then there are the temporary visitors: two runaways, Joe Scott who boxes for profit, Reverend Marlowe, a dubious cynical priest, Mr. Burke, an opportunist, his wife, and their slow son Elias. The singing and dancing parts are supported by other ensemble singers and dancers who don’t have an individual role.

What unites this vast batch of characters are poverty, lost opportunities, and hopes to capture momentary chances, as well as a fleeting desire to change their nemesis. The guesthouse is a filtering space for lost souls, a stepping stone either to the abyss or an unknown, potentially better future. It can also be read as a symbol of our temporary presence on this planet: entering, ideally leaving a mark, experiencing joy and sorrow, and leaving.

The dynamic between the songs that are sometimes referential (for example, “Sign on the Window” recalls Nick’s adultery) and reflect the atmosphere of the plot (“Like a Rolling Stone,” “Slow Train”), and the dialogue portions that aim to forward the story, remain dramaturgically loose and don’t allow for full character development or story arcs. Many of Dylan’s love songs (“Tight Connection to My Heart,” “Sweetheart Like You,” “Is Your Love in Vain?”) are utilized to contemplate the emotional state of the characters who seem rather devoid of being able to love, and are more focused on trying to survive. While the play attempts to present strong-willed female characters, it is very hard to empathize with any character really, as they remain unrounded.

On the other hand, the stage design by Rae Smith (also in charge of costume design) allows for the busy mise en scène to flow between the props, set drums and a piano, dance and choir scenes as well as to resemble the external setting of Duluth. The costumes capture both the style of the time as well as the social status of the characters: while Elizabeth is dressed girlishly, with her headscarf, purse, and box, denoting her readiness to move on, Marianne, Mrs. Nielsen and following ensemble singers wear light short-sleeved dresses, depicting the summer season. Mr. Perry and the Burkes, on the other hand, show off their full pockets through their elegance.

Most of the songs start as solos that are joined by a choir, which was quite enjoyable. Marianne (Sharaė Moultrie), Mrs. Nielsen (Carla Woods), and Gene (Ben Biggers), particularly stand out for the pleasant timbre of their voice. The dance scenes hold elements of swing, but often felt out of context with what we had just experienced in the dialogical part of the piece.

During summer 2023, I experienced the ensemble play Woody Guthrie’s American Song produced by the Mendocino Theatre Company. It is similar to Girl from the North Country, depicting the socio-political time period of the Great Depression, but is straightforwardly focused on the music and life of Woody Guthrie. I was touched to learn where his lyrics and sound were inspired, and satisfied to be presented with a simpler plot. Girl from the North Country aims to interweave a complex time-lapse of various layers, but leaves much to be desired in the untethering process.

The Simon & Garfunkel Story Made New Fans

The Simon & Garfunkel Story, which was at TPAC February 1st, is a must-see for any folk-rock fan. The show spans the entire careers of Art Garfunkel and Paul Simon, and brilliantly recreates all their most renowned works. Aside from the first and last numbers, the performance progresses chronologically, beginning with their 1957 single, “Hey, Schoolgirl,” and ending with their “Concert in Central Park” in 1981. The show is also quite educational, not assuming any prior knowledge and remaining accessible to even the most novice of fans. Simon & Garfunkel’s fantastic music was naturally the focus, but the performers interweaving details about the duo’s personal lives, the energetic four-piece live band, and the video projections putting their music in the context of a radically changing world in the 1960s and 1970s elevated the story beyond the music alone.

The cast – Elliot Lazar as Paul Simon and Max Pinson as Art Garfunkel – were the ones who brought the whole show together. A pair of microphones were set up downstage that the two remained at for most of the show. While the lights and visuals changed, while the live band came on and off behind them, and through several costume changes (including the oh so iconic turtlenecks), Lazar and Pinson remained center stage as a throughline, anchoring the variety of different songs they performed. Though they are listed in the cast as “Paul Simon” and “Art Garfunkel,” they spoke of them more as old friends of theirs, rather than attempting to act as if they were Simon and Garfunkel telling their own stories. I think this was the right choice, as the show is an excellent love letter to their music, and avoided coming off as a corny or pseudo-dramatic performance.

Lazar and Pinson both put on excellent vocal performances throughout the show, and Elliot Lazar also plays his guitar throughout most of the songs.They commanded the stage and their performance to make the audience feel like they were at a rock concert with the live band behind them during “I Am A Rock.” Equally, the James K. Polk Theater felt so small and intimate when they ditched the band during “Bleecker Street,” a song that Simon and Garfunkel performed by themselves in the evenings at New York folk clubs. Though most of the show features the pair singing those iconic folk harmonies together, mainly skimming over their solo careers, Lazar and Pinson do each have a chance to perform on their own, with Lazar singing Paul Simon’s “Kathy’s Song” and Pinson singing “Bridge over Troubled Water.” Both performers brought their incredible vocal support and energy into Simon & Garfunkel’s music in a transformative way, most notably in Pinson’s solo performance mentioned above, my personal favorite number in the show.

The live band at the performance consisted of Marc Encabo on keyboards, Billy Harrington on drums, Jay Hemphill on bass guitar, and Josh Vasquez on guitar. The band also sang background vocals during the larger numbers. The energy the band brought to the songs they performed was palpable, and was not lost on the audience, who were encouraged to clap and sing along. Every time I looked at the backup musicians, they had huge smiles on their faces, always having a blast. Each member of the band also got a chance to play a solo throughout the show, allowing them to showcase their own musicality alongside the cast.

The one thing that was somewhat distracting during the performance was the background video. During the songs, the backgrounds were relatively inoffensive, with abstract images that somewhat corresponded to the lyrics of the music (except for the footage of space shuttles exploding on the downbeats of “Scarborough Fair,” though I admit I may be missing some context there). However, between some of the songs, news broadcasts from the 1960s and 1970s played during the blackouts. I understand that some of the blackouts were necessary for costume changes, but the videos often went on just a minute or so too long. The stories that the performers shared about Simon & Garfunkel didn’t relate to the footage of the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War, making the video feel out of place in the context of the show. Not all the background images were distracting, as the setting for the “Concert in Central Park” consisted of a painting of the park that slowly changed colors. From the afternoon light through the sunset to the evening glow, I did not realize the scene was dimming until “Bye Bye Love,” an Everly Brothers song that Simon & Garfunkel performed at the end of each of their live shows. After “Bye Bye Love,” the performers left the stage before coming back for the encore of Simon & Garfunkel’s greatest hits, ending the night for good with “The Boxer.”

Overall, I left The Simon & Garfunkel Story much more a fan of their music than I was when I came in. The two-hour show made for an amazing night out, and the covers, while bringing a unique twist to their songs, remained faithful to the incredible music of Simon & Garfunkel.

The Simon & Garfunkel Story was only at TPAC one night, but will continue its US/Canada tour through May, for more information see The Simon & Garfunkel Story.

The Lion In Winter; the Circle Players Impress

This is the first production by the Circle Players that I have seen. They are Nashville’s oldest all-volunteer performing arts organization, and it’s clear by the quality of their production how they’ve made it to celebrate 74 seasons. I saw their final performance of The Lion in Winter on January 28th (illness and snow had shut down my two previous attempts to attend), and that’s a real misfortune, because I want to recommend the show highly to you. Everything impressed me: the props, costumes, stage design, the acting, and the play itself.

The Lion in Winter was originally written as a Broadway play in 1966 by James Goldman (whose younger brother William wrote The Princess Bride) and was adapted into the 1968 film starring Peter O’Toole and Katherine Hepburn, which won three Oscars. The hit Fox show Empire is explicitly based on this play, which is historical fiction set at Christmas, 1183, at the court of King Henry II.

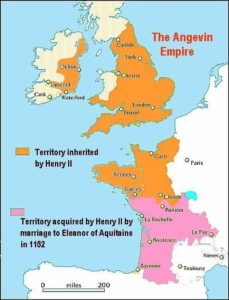

Since most of us Americans don’t know the early Plantagenets off the top of our head, here’s some context: Henry II ruled all of England and half of France, having taken the throne of England less than 100 years after Normandy had conquered it. Infamously, after his former friend Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, gave him much trouble, Henry II uttered the famously hasty line, “Will no one rid me of this troublesome priest?” Four of his knights heard this, took it as a command, and murdered Becket at the altar of Canterbury Cathedral. Even more familiar to us Americans, Robin Hood was supposedly alive around this time as well; Prince John and Richard the Lionheart are present in this play, being Henry II’s sons.

Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry’s wife, was the owner of a massive region in present-day France. Besides being born one of the wealthiest women in Europe, at 15 she married the King of France, Louis VII. The unhappy marriage ended in annulment on a technicality, and eight weeks later, she married Henry II. In the 1170’s, she assisted her eldest son Henry in his rebellion against her husband, which was unsuccessful and resulted in her imprisonment and her son’s death from illness during the campaign.

Enough context and backstory. The play is set ten years after Henry had imprisoned his wife. He is permitting her to join him and their remaining sons Richard, Geoffrey, and John for Christmas. King Phillip II of France, and Henry’s mistress Alais join them as well. Over the course of several days, we see this family scheme, all vying for power, for revenge, for some sort of satisfaction to fill the loveless void in each of them. Henry and Eleanor aim to have different sons succeed him on the throne. His aim is to have a clear successor (the youngest, John) so that the kingdom avoids civil war after he dies. Her aim is to have her favorite son (Richard, the oldest living son) take the throne, and, if she can’t matter to Henry as his wife, she’ll matter to him by defeating him. Plots are hatched and dashed, all with true wit. There are so many clever lines that I can’t pick just one: I’d end up copy-pasting the entire play into this review.

I spend a lot of time here on the content of the play, not to give a book-report summary sort of review, but to emphasize how well-chosen and well-executed this play was. The Circle Players took a play that is full of complex, sustained dialogue calling for a range of acting ability, and they absolutely nailed it.

Let’s start with the stage design: At the two edges of the Looby Theater’s stage stood white two-foot-tall chess pieces, stark against the dark walls. A queen stood with three pawns on one side, a king with three pawns on the other. There couldn’t be a simpler or more elegant way to encapsulate the play visually, before the curtain was even raised. The stage itself had excellent sets: stone walls with spartan but varied furniture, the occasional tapestry or cushioned seat. It put me in mind of Ivanhoe, whose story is set around this time period: “of comfort there was little, and, being unknown, it was unmissed.” The set was shifted quickly and frequently, which was good; plays that all take place in one room can make you wonder why everyone goes to the living room for private conversations.

The props, done by Clint Randolph, were quality, with the best swords and daggers I’ve seen on stage. At one point a character dropped a dagger onto the floor, and it fell with a satisfying heavy metal clang. A lovely large wooden chess board featured in a scene, and people frequently drank from goblets or tankards, pouring from silver jugs or scooping from a hot cauldron. Basically, I wanted to touch everything.

The costumes were well-fitted, distinctive, and quality. I don’t know my fabrics, but these were quality. I am not familiar with 12th century European fashion, but Grace Montgomery’s costumes looked authentic, with varied fabrics, textures, colors, and each character’s garb was distinctive, and matched their character.

The music played as an overture was so good I had to look it up, and yes, it was from the 1968 film adaptation: Main Title/The Lion In Winter. It will make you want to pillage, plunder, and defy the pope. The incidental music occurred only during scene changes and reminded me of the music of the strategy video game Age of Empires II.

I have only praise for the cast. Kay Ayers was captivating as Eleanor of Aquitaine, her controlled vindictive sarcasm and pitiful vulnerability had authenticity and humor, and she shifted between the two smoothly, revealing her character’s snakelike nature. The line between her truth and her lies were difficult to discern, and she made a formidable opponent. Jack E Chambers was charming and nuanced as Henry II, an interesting character: a hearty but smug, who hid his scheming mind behind false frankness and gusto. Elizabeth Burrow played Alais Capet, Henry’s ward and mistress, and gave her a tragic simplicity: out of the seven characters in the play, she was the only one whose goal is not power, but simply to live and be loved. Her half-brother, King Philip of France, was played by Matt Stapleton with smug bitterness, his carefree arrogance hiding his obsessive vindictiveness. The sons were troubled pawns in the battle between their parents. Sawyer Latham embodied Richard Lionheart, Jeffrey Luksik exuded clever, resentful insignificance, and Ezra High played a petulant, childish John.

Clay Hillwig directed a fantastic production, each individual component coming together to create an amusing and moving experience. The Circle Player’s run of The Lion in Winter is over, but their season isn’t: their next production will be The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas March 15-31.

Preview of ‘Indecent’ coming at TPAC

Inspired by the true events surrounding a controversial 1923 Broadway play, Paula Vogel’s Indecent tells the behind-the-scenes story of the courageous artists who risked their lives to perform a work deemed “indecent” as it journeyed from Warsaw, Poland, to Broadway in the early 20th century. “One hundred years later, we’re still fighting the same battles. Censorship is rampant in our society,” say director Micah-Shane Brewer. “We’re facing an unprecedented resurgence in anti-semitism. Laws are being passed all across our country solely for the purpose of marginalizing certain populations.” Indecent is a love letter to the power of theatre, a cautionary tale of the consequences of censorship, and a reminder that love always triumphs over hate.

In Indecent, an ensemble of 10 actors and musicians plays over 40 different roles following the trajectory of Sholem Asch’s controversial play God of Vengeance, one of the first plays by a Jewish playwright to open on Broadway. With a klezmer-infused score filled with joyous songs and dances, this play invites audiences to explore themes of love, strength in community, and taking a stand in the face of censorship.

The Nashville Repertory Theatre will be performing Indecent at TPAC’s Andrew Johnson Theater February 2-11. See Indecent | TPAC for tickets and more information.

From the Nashville Shakespeare Festival

Pop-Upright Shakespeare’s Richard III: Historical Tragedy for Fun

The Nashville Shakespeare Festival does more than their Summer Shakespeare. Besides partnering with local universities for winter or spring plays, they do staged readings. Or in this case, a “pop-upright” performance, with actors moving around the stage with book in hand and with minimal props or costumes. The play, including a brief intermission, took about 2 hours and 15 minutes.

This took place on January 27 at The Loading Dock, a cozy coffeehouse off of Wedgewood in sight of 65, full of plants and local art for sale. My americano was bright and my breakfast bagel sandwich delicious with thick bacon and the correct egg to cheese ratio. Downstairs from the cafe is a lobby/gallery area between Arde Motors, some offices, and Killjoy’s Booze-Free Beverage Shop (which had a steady stream of unobtrusive customers during the performance). The stage was not raised, but an empty rectangle at the head of the room with the actors’ chairs lining two sides, facing each other. Comfortable chairs for the audience were set out with an aisle down the middle. There were no stage lights, no microphones. I was glad of that: in such an intimate space sound systems are always too loud and create a sense of artificial distance. Besides, Shakespearean actors know how to project to the audience, and we could hear clearly.

As the show started, Denice Hicks, the Artistic Director of the Nashville Shakespeare Festival, told us that this pop-upright hadn’t had a rehearsal; the words would be Shakespeare’s, but much of the acting would be improvised. The audience was invited to be vocal, to react, and specifically to sing “dum-dum-DUM” each time someone said “the Tower” referring to the Tower of London. The audience actually did, and people booed and hissed with cheerful gusto when Richard the III was crowned. Some people in the crowd read along with the performance, following the words on their phone or with a paperback copy.

The cast had a few props: nerf swords, hats or scarves or jackets to denote different characters, and several shiny crowns; its cheerful casualness it reminded me of high school English projects where students had to perform a scene from the semester’s play– except with many talented actors who can speak iambic pentameter with flow.

The time period this historical play is set in is convoluted and confusing. To understand much of the history requires lots of backstory and explanation of legitimate and illegitimate births and family trees. Game of Thrones is based, very loosely, on this period, called the War of the Roses, a time of civil war in England from around 1455-1485. The royal House of Plantagenet had rival factions within it, the House of York and the House of Lancaster, both of whom had claims on the throne. Both sides gained and lost the throne several times, resulting in five kings in 25 years, three of whom were killed by their rivals. The bloodshed and unrest ended when Henry Tudor (later Henry VII) defeated Richard III in battle and married Elizabeth of York, uniting the Lancaster and York families. In Winston Churchill’s History of the English-Speaking People; The Birth of Britain, he called this period “the most ferocious and implacable quarrel of which there is factual record… It was a conflict in which personal hatreds reached their maximum… The ups and downs of fortune were so numerous and startling, the family feuds so complicated… Only Shakespeare… has portrayed its savage yet heroic lineaments. He does not attempt to draw conclusions, and for dramatic purposes telescopes events and campaigns.” – The Birth of Britain

Richard III follows the eponymous villain as he schemes his way to become king and then loses the throne and his life. He tricks his brother King Edward IV to imprison their other brother, Clarence, whom he then has murdered in the tower. He manages to woo and marry Lady Anne, winning her over with smooth words despite the fact that she knows he killed her husband and father-in-law. After King Edward IV dies of sickness, Richard manages to send the children next in line to the throne to the Tower of London. The rest of the family is furious but powerless. He gets a lot of people executed or murdered (including the children and his wife) and wins the throne. He schemes to marry his niece, Elizabeth of York, but instead is defeated and killed in battle by the virtuous Richmond, who marries Elizabeth of York instead and becomes Henry VII, beginning the Tudor dynasty– the dynasty in power when Shakespeare wrote this play. Richard III is about a machiavellian man who manipulates others by lies, charm, threats, and murder. He’s fascinating and evil. You love to hate him. Denice Hicks’ abridgement of the play was clean and clear.

Such a tragic play with such scheming and treachery and murder is incongruous with nerf swords at a coffee shop, and the Nashville Shakespeare Festival took full advantage of that. Although many moments were played straight– “Now is the winter of our discontent,” “A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse,” etc– much of the drama was played with cheerful melodrama, and acidic asides were made goofily satisfying. The improvisational feel melded perfectly with this shift of mood; it had improv energy while people spoke pure poetry. It really worked. I laughed loudly at the comedy of two henchmen (the talented Matthew Benenson Cruz and Bob Roberts) as they murdered Clarence. At one moment, as Richard is explaining some of the family tree and his reasoning to marry Elizabeth of York to establish himself as a more legitimate heir, Caroline Conner (who played Buckingham) acted hilariously confused and muddled by his explanation.

Denice Hicks, the artistic director, announced the stage directions to the audience, giving the scene, location, and some of the character names, but she also played Queen Margaret in a few scenes. At one point, she introduced a scene, then flipped a shawl over her head and began speaking as her character. The actors on stage turned to look at her and she quickly told them, “You can’t see me, this is an aside.” They hastily turned away, but later in the scene Andrew Johnson turned to face another character as Hicks was speaking and she waved him away, “You can’t see me,” and he called back, “I’m not looking at you.”

Much of the cast was familiar, Nashville Shakespeare Festival regulars. All did a great job. Andrew Johnson (who played Benedick in last summer’s Much Ado About Nothing) was fantastic, funny, and full of range. Joyce Torres had a fun husky regal air when she played the Duchess of York, Katie Bruno was comic and cutting as Queen Elizabeth (not either of the Queen Elizabeths you’re thinking of) in her argument with Richard. Bob Roberts played the drums, giving literal badum-tsch sound effects. A few times he delivered lines on stage and quickly turned to hit the hi-hat with a nerf sword. He and Matthew Benenson Cruz were expressive and probably the funniest part of the show to me, as Richard’s henchmen.

The final lines in the play, “Now civil wounds are stopped, peace lives again./That she may long live here, God say amen.” The cast gestured to the audience to say it along with them, and we did. To anyone that suggests the Nashville Shakespeare Festival perform another pop-upright play, I say amen.