Come to the Cabaret at Studio Tenn

This is Studio Tenn’s first year in their new digs, the Turner Theater. Though a bit difficult to find within the maze of parking spaces, shops, and eateries, it was worth the trip.

In a pleasant surprise, Paul Vasterling, Artistic Director Emeritus of the Nashville Ballet, served as both director and choreographer. Technical matters of getting sets on and off stage were smooth, seamless, and the use of the space, lined with lit globes was masterful, particularly evocative with the first few rows of audience seating arranged with closely spaced nightclub tables and chairs. Though part of the original staging, the scene where characters are within arms’ reach, but still call one another on black telephones seemed offkey. Otherwise, the minimalist set onstage—a bed, a table, a few chairs, all quickly removed—was quite effective; the overall staging was excellent.

Prior to the overture downbeat, Studio Tenn’s artistic director Patrick Cassidy gave a bit of the history of a show that originally premiered in 1966. With each revival, this tale of the hedonistic days in Berlin overlapping with the rise of Nazism in Germany, retains its strength to entertain and move audiences worldwide, winning multiple awards with each incarnation.

Part of its continuing relevance today mirrors the current international zeitgeist where some citizens glory in, and eagerly embrace, the possibility of authoritarianism, while more fear and flee it, as others fiddle as Rome burns, and yet more bury their heads in the sand, deciding to ignore or accept whatever is to be. All this results in, quite simply, a great show. Like South Pacific, Oklahoma, West Side Story, a bigger societal picture shines through the smaller lens of one island, or one region, or one neighborhood. In this case, one nightclub.

The KitKat Club is both a real and metaphorical locus where the Emcee runs the show and two ill-fated couples, Cliff and Sally (an American writer and English showgirl), Herr Schulz and Fraülein Schneider (both Germans: a widowed Jewish greengrocer and a single middle-aged proprietor of a boarding house) meet and separate. Ancillary characters, Ernst Ludwig (Matt Logan) and Fräulein Kost (a smuggler who joins the Nazis and a prostitute working out of the boarding house) represent the impending political and moral threats facing all of Germany.

All the voices were strong and effective, matching the quality of the tight pit band (Stephen Kummer, conductor), awkwardly divided onto two sides of the stage. The acting also revealed a depth of talent with the best matches of talent-to-role going to the Emcee (Brian Charles Rooney), Cliff (Caleb Shore), Herr Schultz (Matthew Carlton), and Kost (Jordan Tudor). Their clear grasp of their characters allowed the audience to settle into the story.

Interestingly, despite Vasterling’s deep levels of experience, much of the choreography amplified the most visceral weaknesses in the cast—their bodies. With only one exception, most of the women did not seem to know what to do with their bodies. It may just be transferring a pure classical ballet sensibility to a more carnal environment, but the sensuality of decadent nightclub dancers and licentious ladies of the evening was noticeably absent, as if good girls on rumspringa were trying too hard to be bad. Only Tudor as Kost, had the subtle sexuality that made her depiction of a prostitute convincing.

Megan Murphy Chambers, on the other hand, not only didn’t have the English accent the Sally Bowles character required, but was implausible as a “seen everything” showgirl sleeping her way to the top, each undulation approached with practiced determination. When singing major numbers, she and Julie Cardia as Fraülein Schneider both stood rather stiffly as they belted out the show’s potent lyrics in true Broadway style. The quality of their voices was so bold, so skilled, it almost overshadowed the ongoing discomfort I felt at some indefinable absence, some missing element. I was finally able to define it when Rooney sang.

The emcee role was the most challenging both vocally and in acting, going from flirtatious through bored laissez-faire, from sexual hijinks, through growing awareness of the threat against him and his community. At the end, dressed in prisoners’ stripes and a decal representing the Nazi pink triangle, his poignant despair emanated throughout the room. Some nearby audience members joined me in gentle, but audible gasps. Before that, though, when he sang “I Don’t Care Much,” he moved almost as little as Chambers and Cardia, but each move, each head tilt, each hopeless raise of the eyes toward the heavens was so meaningful that the light went on. That is what I’d been missing, the connection of body to emotional moment, acting and singing with your whole self.

In the end, though, this was a well-produced program of solid quality that definitely made for an evening that was both enjoyable and thought-provoking. I hope this company will consider the occasional move past the greatest hits into a play by a local playwright. Perhaps a night of one-acts? Their skill would give talented writers in the Nashville area a serious chance to promote their works, just as the Nashville Ballet allows its dancers to choreograph a talented company. Seeding the growth of a new generation of playwrights would add to the gift Studio Tenn already provides audiences.

This is the final show of the season, but if it is any indication, 2024–2025 Rockin’ Retro season tickets, starting with Little Shop of Horrors and ending with Jersey Boys, would be well worth the cost.

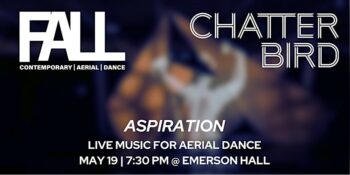

FALL and chatterbird in Collaboration

A Bending of Its Own Kind: Aspiration

On Sunday May 19th, chatterbird, a Nashville-based chamber ensemble, collaborated with aerial and contemporary ballet company FALL for their latest performance: A Bending of Its Own Kind: Aspiration. Founded in 2014, chatterbird “…explores alternative instrumentation, stylistic diversity, and interdisciplinary collaboration in order to create thoughtful, intimate, and inventive musical experiences.” FALL was founded in 2010 by Rebekah Hampton Barger to articulate the experience of those living with chronic pain and illness. A Bending of Its Own Kind is a dance performance piece created by Barger about her experience with severe scoliosis and chronic pain. As the years have gone on, the piece has expanded to include the stories of other individuals with chronic pain and Aspiration is the latest installment, which explores the connections between hope and breath, and what each of those means in the face of living with a chronic condition. In an interview with MCR, Barger cites a quote by Ted Chiang as inspiration for the title of the piece: “It is no coincidence that ‘aspiration’ means both hope and the act of breathing.” The music and movement for this piece were developed separately, with both choreographer and composers drawing inspiration from a discussion between five individuals who each live with a form of hypermobility disorder, along with several other comorbidities. During this performance, the composers performed a structured improvisation alongside the dancers.

A Bending of Its Own Kind: Aspiration was performed in Emerson Hall, a refurbished 1930’s-era church that had a space for a small ensemble: harp, gezheng (a chinese stringed instrument), violin, bass, and synth and percussion, along with two sets of aerial silks in a large metal frame. The performance included four pieces with four individual dancers: Hope // Breath, Knowledge // Empowerment, Looking Forward // Looking Back, and Grace // Acceptance, and a final work in which the four dancers performed together: Aspiration (in three parts).

In the first part, Hope // Breath, Marisa Pace danced from one set of silks to the other, lifting them in a way that imitated the billowing sails of a ship. At one point she climbed up the silks and waved her arm like a bird in flight. Light on her feet, Pace beautifully illustrated the idea of hope. Jasmine Clark took over for Knowledge // Empowerment, climbing the silks and standing with her back straight, tall and in charge. She even moved the silks in such a way that she looked as though she was swinging effortlessly on a swing set. In Looking Forward // Looking Back, Alex Winer moved back and forth from one set of silks to the other, seeming to get stuck in the past, although reaching forward to the present. The struggle in reconciling the past with the present was evident in Winer’s frantic movements. Josie Baughman enters while Winer is still wrapped in the silks of the past, and frees her before starting the final piece, Grace // Acceptance. Baughman moves powerfully, climbing the silks and throwing her arms wide, embracing her reality. There is peace in this final work.

Aspiration (in three parts) begins with the sounds of slow breaths with all four dancers struggling to breathe or perhaps breathing through incredible pain. The jerky movements include strange positions with arched or curved backs and arms pressed against chests as they fight for breath. They move into frenetic dancing as they throw and twist the silks in a way that is almost opposite of the beautiful, soft billows of the Hope // Breath. At some points the dancers are in sync and at others they seem to be working against each other, until they begin to lean on each other. The poignant beauty of them holding each other up reminds the audience that we must help each other, love one another, and uplift one another. Those with chronic pain rely on each other for understanding, compassion, and assistance.

The music was unobtrusive, providing a background meant to enhance rather than overcome. Because these are structured improvisations, there was a “sameness” to the works, one piece blending into the next. I believe some of the dramatic effect is lost during improvisation, as they are unable to punctuate specific moments in the dance. However, the overall affect was beautifully dreamy, especially as night fell and the light coming in through the windows faded. Wu Fei on the guzheng in particular contributed to the ethereal nature of the pieces. Other members of the ensemble included: Timbre Cierpke on harp and vocals, Annaliese Kowert on violin, Paul Kowert on bass, and R. Aaron Walters on syth and percussion. As someone that struggles with a chronic illness on a daily basis, I was so grateful for this work and its exploration of chronic pain and illness. I particularly liked how the dancers embraced the painful or difficult moments, and still were able to find joy and peace.

Did you miss the chance to see this performance? I have good news for you: the musicians’ performances will be captured and incorporated into a performance of the full-length production of A Bending of Its Own Kind on June 1 and 2 in Knoxville, TN, hosted by Dragonfly Aerial Arts and Circus Studio.

A review of POTUS: Or, Behind Every Great Dumbass Are Seven Women Trying to Keep Him Alive

Nashville Repertory Theater closes its 39th annual season in a promising and open-ended tone with the staging of POTUS: Or, Behind Every Great Dumbass Are Seven Women Trying to Keep Him Alive. Before I start reviewing the show, I would like to clarify that my reference to the assumed/assigned genders of the characters is based on the official descriptions made by the playwright and the team that has realized the staging of this play.

Selina Filinger’s 2022 play is a farce where seven exceedingly witty women pan out in clumsy actions and humorously embarrassing events. They are all closely related to the president of the U.S. but that is not the only thing they have in common: POTUS makes an unforgivable sexually denigrating gaffe towards the first lady, one that snowballs the already fragile global political relationships and the seven of them will put everything they are and ever wanted to be at risk, to save the president’s reputation. As they try to pull the most powerful man in the United States out of the gutter that may have repercussions on world peace, they reinforce their own denigration and oppression, while each of them is in fact much worthy and capable of being the president of the country themselves.

Director Lauren Shouse who introduces the play to Nashville audiences, forwards Selina Filinger’s dedication of the play to “any woman who has ever found herself as the secondary character in a male farce.”

It is rather tragic really, to see these seven bright women chasing their tails around the stage, trying to cover up for a ubiquitous man whose only physical presence is that of his lustrous black shoes. The play is staged in two parts, with a 15-minute break in between, which offers enough time to imagine the direction the show will take during its second part. Do we anticipate the animosity between these women to wrongfully confirm the hysteria etiquette historically labeled on women as a weakness, utilized to keep them away from important leadership positions or is the play going to take a more optimistic turn?

In terms of staging, the crescent moving stage walls representing the inside of the White House, designed by Gary C. Hoff as well as the snapping instead of sliding blue-ish lights designed by Darren E. Levin enable the short scenes to sink in and flow with a smooth tempo while allowing the audience to delve into laughter.

The first lady, Margaret, played by Tamiko Robinson Steele, is brilliantly cynical due to being overqualified yet diminished to hosting sumptuous events . Chris, played by Kris Sidberry, a black journalist determined to advance in her career while a single mom of twins, bitter sweetly running around with milking pumps dangling from her top, corners and criticizes Margaret (written to be played by a black woman) as not caring about black women’s struggles, but Margaret answers something along the lines of “I don’t subscribe to identity politics”. These are very interesting threads of potential discussions that unfortunately don’t get developed in the play, as the focus is sucked by the omnipresent but physically absent POTUS.

Lauren Berst is very believable as the chief of staff Harriet, an octopus of a woman, trying to cover up for multiple diplomatic cracks from behind the scene, while Jean, the president’s handler, played by Tamara Todres appears to be on top of her game, until her achilles heel, her ex-lover Bernadette, president’s sister shows up. Bernadette, played by Rachel Agee, an ex-convict waiting for the presidential pardon, infiltrates misdemeanor in what is supposed to be the exemplary house of the rule of law.

The sound of the show, designed by Sara Johnson adds an enriching texture to the slapstick short scenes. Pop feminist songs juxtaposed by patriotic rock songs interpreted by Dusty (Quincey Lou Huerter), the farm girl, fortuitously entering the White House drama and the insecure yet ambitious Stephanie played by Darci Nalepa Elam, add much spice to the show.

The negligent annotations among the characters about their haircuts or the costumes they are assigned to (designed by Melissa K. Durmon), not sparing here POTUS’s crocs slippers, may be read as a reinforcement of the stereotype but they may also be read as a critical commentary on the judgmentalism of appearance among women. In his essay on art criticism, English art critic, novelist, painter and poet John Berger writes “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.”

At the end of the play, the seven women unite, realizing they can only stand against the patriarchy together. Their gaze is turned towards the audience. They are not watching themselves being looked at; what they see is their future selves, taking over.

I often feel conflicted about laughing at serious issues, on the other hand, laughter is a way for humans to ridicule themselves and this surely is healthy for the ego. The show was utterly entertaining, and it brought lightness to the quite heavy topics it elaborates.

From Our Far-flung Correspondents Series:

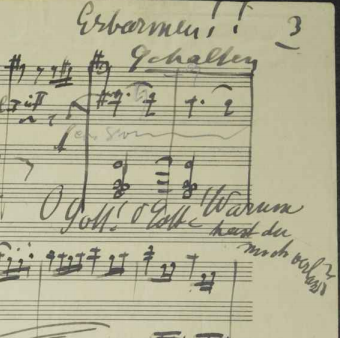

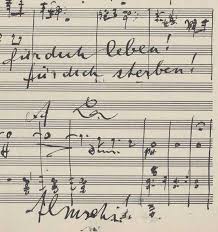

“Colorado Symphony – A Mile Above with Smyth, Prokofiev, and Brahms”

Performing at 5280 feet above sea level and giving at least 5281 reasons to fall in love with the Colorado Symphony, the music of Ethel Smyth, Sergei Prokofiev, and Johannes Brahms dazzled.

Celebrating its centennial artistic season, the Colorado Symphony is the only full-time professional orchestra in the greater Denver region. Presenting performances in various categories – Classics, Symphony Pops, Spotlight, Family, Holiday, Movie at the Symphony, and Alternative – the organization strives to fulfill its mission of being, “The future of live, symphonic music.”

The Colorado Symphony’s primary residence is Boettcher Concert Hall. Built in 1978 and renovated in 1993, this venue is part of the Denver Performing Arts Complex, which also houses the Colorado Ballet, Denver Center for Performing Arts, Opera Colorado, and various national acts, local groups, festivals, conferences, and public events. Boettcher Concert Hall is the nation’s first symphony hall constructed in the round, resulting in 80% of the audience seats being within 65 feet of the stage. The seats themselves are also unique, having been designed with steam-bent plywood that acoustically simulate a full house regardless of actual audience size.

Before concerts within the Classics Series, violaist Catherine Beeson prepares interested patrons with a lecture that introduces the music soon to be heard in performance. Beeson makes materials available cited within her lectures, called Preludes, on her personal website within the Cool Nerd Stuff section. For this concert, Beeson crafted a thread through the program’s three pieces, the genesis of the lecture taking inspiration from High Anxiety, the psycho-comedy starring Mel Brooks.

Catherine Beeson is a perfect guide, able to introduce novices to concert music, while still providing enough content for those more learned – and all of this while making connections to current societal happenings. For example, Beeson referenced the current rap battle between Drake and Kendrick Lamar before introducing the following nuance about Johannes Brahms’ Symphony No. 3 and his well-known feud with Richard Wagner:

Random drama for you to chew on: Even though Brahms respected his work, he and composer Richard Wagner had a pretty nasty public feud going on, and even though Wagner died months before Brahms composed Symphony No. 3 the fur was still flying in the community so much so that Wagner supporters tried to wreck the Symphony’s premiere.

Random conspiracy theory for you to chew on: In his Symphony, Brahms included a musical quote from Wagner’s [Chorus of Sirens]. The spot on the Rhine River where Brahms composed the Symphony is also very near the infamous Lorelei rock cliff, named after the siren-like water spirit that lured sailors to crash their ships. Was [Brahms] honoring Wagner’s composition skills, mocking his death, OR WAS HE PREDICTING ETHEL SMYTH’S 1904 OPERA THE WRECKERS AND THIS WEEKEND’S PROGRAM LIKE A SYMPHONIC NOSTRADAMUS. You be the judge.

Shortly after Beeson was done preparing our listening, the Colorado Symphony took to the stage wearing all black, contrasting guest conductor Jun Märkl, who wore white tie and tails. Märkl serves as music director of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra and Taiwan National Symphony Orchestra, will become the chief conductor of the Residentie Orchestra the Hague beginning in 2025, and performs as principal guest conductor of the Oregon Symphony. The Colorado Symphony played well for Maestro Märkl throughout the evening; perhaps the aforementioned disconnectedness with respect to wardrobe didn’t penetrate the artistic relationship between conductor and ensemble.

Opening a concert with Dame Ethel Smyth’s “On the Cliffs of Cornwall,” Prelude to Act II from The Wreckers was an interesting choice; however, a choice seemingly fitting of a composer who defied convention to the point of becoming an imprisoned suffragette. Some have submitted that the opera The Wreckers is thought to be the most important English opera composed in the 300-year period between Henry Purcell and Benjamin Britten. Principal oboist, Peter Cooper, and Michael Thornton, principal horn, helped support such a submission with the solo melodies they offered that became increasingly enticing as the work developed. The Colorado Symphony played with such sensitivity to ensemble balance, often replicating what has become expected of an audio recording that has undergone post-production editing.

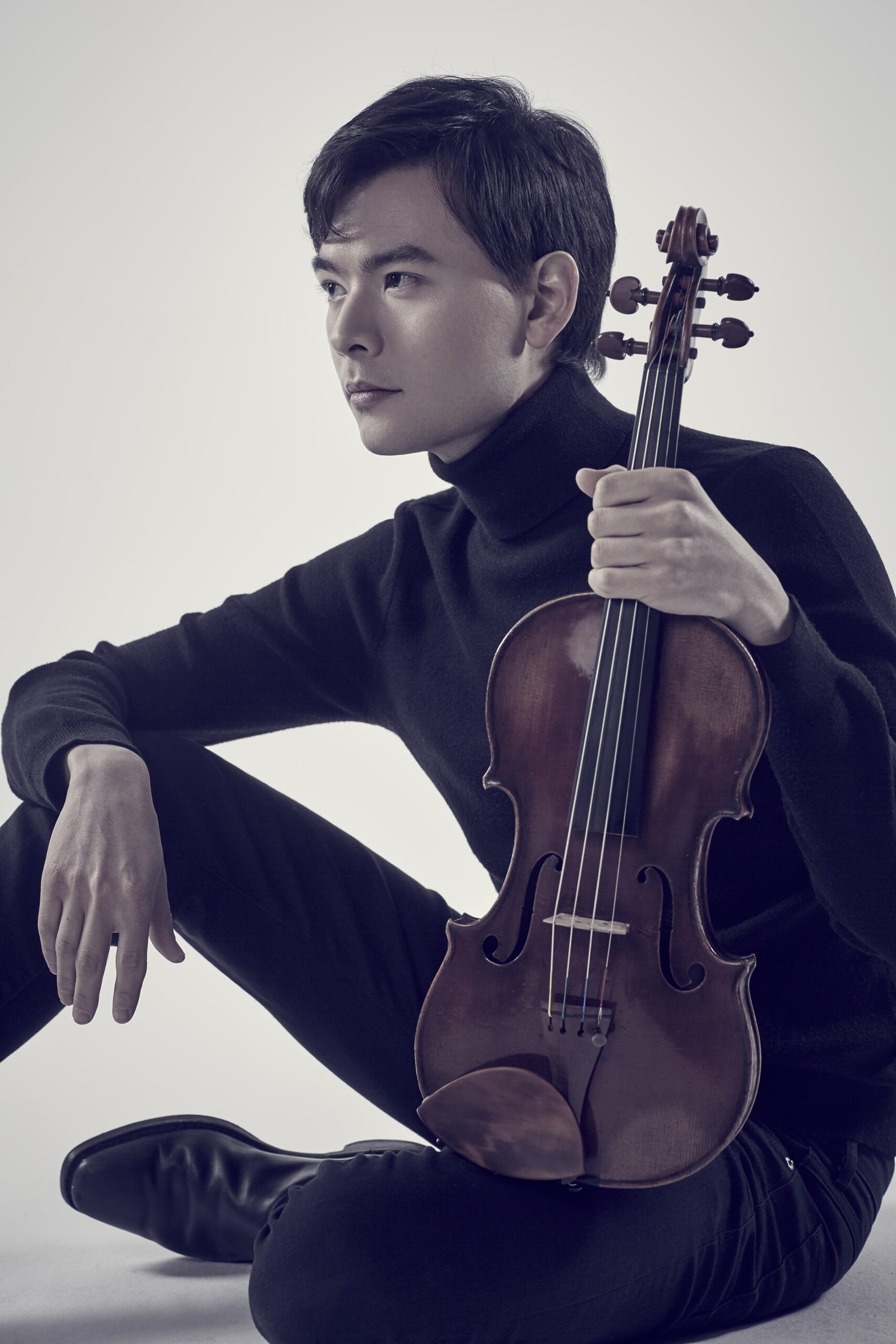

The second piece offered was Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor, Op. 63 of Sergei Prokofiev, with soloist Stefan Jackiw. This season alone, Jackiw is scheduled to perform with the New York Philharmonic, Taiwan Philharmonic, and the China National Symphony, in addition to presenting multiple world premieres at Roulette, curating a series of programs for the Edinburgh Festival, and making a debut with the Junction Trio (Conrad Tao, piano; Jay Campbell, cello) at Carnegie Hall.

Jackiw’s intonation was impeccable and matched by the flute-oboe-clarinet sections throughout some rather exposed moments. The bassoon playing was equally impressive, although decidedly more present than what may have been expected. Maestro Märkl often asked the ensemble to play quietly to powerful affect, but when then asking for a more present volume, the result seemed to be an out-of-portion dynamic cliff that was navigated less gracefully in order to be achieved. Stefan Jackiw’s technical abilities towards the end of the Concerto were hypnotic with precision, much like the way musicality oozed from his soul throughout the 2nd movement. A final accelerando to end the composition left some in the orchestra catching up, but a tempo risk that should continue to be encouraged, nonetheless.

The Colorado Symphony ended the concert, or so the program suggested, with Symphony No. 3 in F Major, Op. 90, by Johannes Brahms. This worked proved to be the highlight of the program, in part to the way in which the cello section contributed to the composite. Seoyoen Min, who performs from the Fred and Margaret Hoeppner Principal Cello Chair, led powerfully throughout tutti melodic moments in the 3rd movement. Credit should also be given to principal trumpet, Justin Bartels, for using rotary trumpets on this piece. Brahms composed an ending that recedes in both activity and dynamic. The pacing of this section, in particular the final release, felt a bit abrupt. Fortunately for concertgoers, a planned encore of Brahms’ Hungarian Dance No. 5 left all happily bouncing out of the concert space.

Following performances within the Classics Series, conductors and/or soloists make themselves available for a question-and-answer session with audience members interested in extending their experience. Both Maestro Märkl and Jackiw participated, thoughtfully responding to a variety of questions about both the music and their lives. From the Prelude with Beeson, the performance, and the Talkback with conductor and soloist, one can quickly become rather invested to the Colorado Symphony – even more so when one is able to share such a thorough experience with someone special, as I was able to do with my first band director, Gary Hoffman.

It feels appropriate to offer the idiom that the sky is the limit for the Colorado Symphony, but the group already performs in the sky. To infinity and beyond, then, for the Colorado Symphony!

Frozen: Perfectly Fine

The film this musical is based on was such a hit in 2013 that anyone alive then or since then is at least aware of it, its characters, and can hum “Let it Go.” I’ve seen near infinite Frozen merchandise over the years, ranging all the way from boxed Mac & Cheese to men’s sweaters. I was a teenager when it came out and saw it in theaters with friends, enjoyed it and even bought the album off iTunes (possibly the last digital album I ever bought). In this review I’m going to assume that you’re seen it, because if you maintained the effort to avoid seeing it for the past eleven years you’ll have no interest in this review anyways.

Disney took its time making the adaptation, which made its Broadway debut in 2018, continuing until the COVID lockdown. The North American Tour began in 2019 and continued after the COVID interruption, playing its 1,000 performance earlier this year. Jennifer Lee, who wrote the film, did the book, and the original song-writers for the film, husband-wife duo Robert Lopez (co-creator of The Book of Mormon) and Kristen Anderson-Lopez wrote the new music for the Broadway adaptation, promising at least the potential of equally good songs.

Before going in to see it, my greatest hope for the Broadway adaptation was that the notable lopsidedness of its music would get balanced: the first half of the movie has seven fabulous songs, some almost back-to-back, yet the second half has only two, one of which is a reprise. Perhaps the plot would get fleshed out a little too: they’re orphaned as children and Elsa isn’t crowned until she comes of age, but there’s no a regent, or even anyone in an authority position. There’s nobody to take the command of the land when the princesses disappear except for some random foreign prince who is unofficially engaged to the younger princess. I also hoped Kristoff would be likable, his personality expanded beyond being a crude masculine stereotype.

The adaptation doesn’t give new depth, but parts are changed: Elsa is shown to have a little more compassion and care for others. Kristoff is indeed improved, now a somewhat brusque but kind and independent man who is an outsider rather than a loser. Hans is also better, maybe because they didn’t give him those creepy sideburns. The scheming ambassador from Weselton still basically does nothing, but is funnier. Sadly, though, Anna (my favorite character in the film) is now slightly annoying. Most notably, there are no rock trolls, but “Hidden Folk,” rustic people half-dressed in wild nordic furs. It’s an understandable choice, but it would have been delightful to watch a lavish puppet show for the trolls (the animated trolls do have a rather Muppety look). Instead, the Hidden Folk deliver the same lines while doing a squatting-swaying movement in an attempt to convey wildness.

The adaptation tries to add a few jokes for the parents by adding clumsy innuendos. Anna’s song “For the First Time in Forever,” has its tone shifted by these jokes, from being joyful and hopeful to a little, well, horny: Anna strokes a bust of a man’s muscular torso, and then later, when singing with Hans, puts her flat hand on his chest and slides it a few inches lower towards his crotch. It is unexpectedly awkward. This isn’t helped by the fact that the woman playing teenage Anna is clearly an adult. Usually innuendos make me chuckle, but these annoyed me, probably because they change the tone of the innocent Disney brand fairy tale.

Obviously, the music is a big part of the musical, particularly the new songs created specially for it. It was an impossible task. To begin with, most viewers are lovingly familiar with all the songs from the movie. So how can you insert new songs in the same story and not have them feel like interlopers? The new music is fine, but not particularly memorable, and at times feels a little retro-80’s pop unlike the film’s music. One musical choice I actively disliked was the replacement of the “For the First Time in Forever (Reprise)” when Anna finally confronts Elsa in her ice castle. It’s such a thrilling musical moment with an expert blending of their two contrasting melodies, and it was replaced with an unfamiliar song communicating mostly the same thing, except now without Anna. At least now the number of songs in the second act make it feel more balanced, as I had hoped.

The musical’s special effects have been talked up, and they aren’t bad. Most of the effects are flashes of light, sprinklings of snow, and well-designed projections casting a limn of frost over the stage. A few moments are surprising, ice-like confetti appearing from unexpected places, or when young Elsa and Anna build a moving Olaf from toys in their bedroom. My favorite effect is at the end, when Anna is frozen. The ensemble has been dancing around in all-white attire, personifying the blizzard, and suddenly they join her, draping a massive cloth over her and themselves. At that moment they become motionless and the projectors blast a perfectly designed image of frost over them. They truly look frozen. The moment that got the biggest gasp from the crowd is during Elsa’s “Let it Go.” In the film there’s a moment when she magically transforms her dress. Here they have her on a high portion of the stage and she dramatically throws her arms down to have the dress suddenly ripped off to reveal a sparkling dress underneath.

The special effects and costuming meet to create Olaf and Sven. Olaf, the dismemberable snowman, is a large chest-high puppet, attached to the actor playing the role. He moves the mouth and hands of the puppet, and the Olaf’s feet are attached to his own. The actor wears an all-white Scandinavian outfit with a funny hat. The puppet is fun to watch, and you can see the actor’s face for more detailed expressions. Sven, whom I found boring in the film, is the coolest thing on stage. The detailed design is cool, with an animatronic look and movement to its features, but containing a person who nimbly walks around on all fours. I found myself staring at Sven every moment he was on stage. To see a quick montage of the costume, piece by piece, see The Secret Life of Sven – The New York Times.

The costumes are lovely and lavish. Even the common people’s attire have many layers of cloth, which they use as they dance to create added movement. The ensemble’s choreography is fun, especially at the ball, but the main characters generally just stand and sing. The new song to start off the second act, “Hygge,” involves a goofy “nude” chorus line of sauna-goers who always manage to cover themselves up with tree branches, and it got a lot of laughs.

The set pieces are great, massive and with layers giving added depth to the stage. The backdrop is a large screen, and it’s used exactly as it should be: as a backdrop. It works well with the set pieces and deftly joins in with the special effects of frost and snow. My favorite set is the castle, with its attractive wood walls and designs.

I saw the show Wednesday, May 8, so the audience was smaller than it would have been had there not been tornadoes. A large swathe of the crowd was families with children, boys and girls. Most of the girls were in some degree of Elsa attire. I discovered that TPAC has booster seats for Jackson Hall. The kids behaved well, although at one point, when Olaf sings his song “In Summer,” there’s a classic joke, “Winter’s a good time to stay in and cuddle, but put me in summer and I’ll be a [comical pause] happy snowman!” Some little boy towards the front yelled out “Puddle” with uncontrollable enthusiasm in that moment of quiet and got everyone to laugh, including Olaf. During intermission kids were hyper and happy: the show kept them engaged and they seemed to enjoy it a lot. The musical is barely longer than the movie, and that is counting the one twenty minute intermission.

Caroline Bowman does a fantastic job as Elsa (a must when we’re all familiar with Idena Menzel’s version). Lauren Nicole Chapman has a strong, capable voice. Nicholas Edwards makes the best version of Kristoff, a marvelous singer and a winning actor. Preston Perez makes Hans actually charming and I wish we could see more of his villainous side. Jeremy Davis is eminently likable and has perfect comic timing as Olaf, puppeteering smoothly. Weselton is played by Evan Duff, who makes the character’s bad dancing hilarious. Dan Plehal played Sven the night I attended with impressive agility.

I took a lot of space here to say something simple: the musical is a solid adaptation of an excellent children’s film, and it faces all the usual limitations of adapting from animation to live action. Too big to fail, Frozen: The Broadway Musical would be a hit even if everyone involved completely dropped the ball. Luckily, they didn’t. Adults will find it good enough, superfans will automatically love it, and the kids will really enjoy it. For children new to Broadway Frozen could be a good way to start their experience.

Frozen will continue at TPAC’s Jackson Hall through May 18. For tickets and more information, see Disney’s Frozen | Broadway Shows in Nashville at TPAC or Disney FROZEN | The Broadway Musical.

The MCR Interview

Fall Dance Director Rebekah Hampton Barger on Dance, Chronic Pain and Her Collaboration with Chatterbird

Rebekah Hampton Barger is the Founder and Artistic Director of Nashville-based aerial and contemporary ballet company Fall. She recently zoomed with MCR journalist Bethany Morgan regarding her work, and approaching collaboration with Chatterbird. The following is a recording of that conversation (please like, subscribe, and share!):