The MCR Interview

Nashville Ballet NB2 Director Maria Konrad on Dia de los Muertos

Angelica Trujillo conducts an interview that serves as a wonderful introduction to the new director of Nashville Ballet’s NB2 Troupe, Maria Konrad, as well as a thorough introduction to the ideas and aesthetics behind Konrad’s choreography for this world premiere of Día de los Muertos. Issues in presenting and mingling ballet, contemporary dance, folkloric dance and movement onstage are discussed. Dancer Nicole Bustamante answers a few questions on her own perspective of the work. The basic narrative of the ballet, including the primary characters, Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Carlos Chavez, and Lola Avarez Bravo. Linares’ Alebrijes, their appearance and creation (with 3d printing) for the performance are discussed. Like, Share and Subscribe!

Moulin Rouge! The Musical

Ten years ago I saw Moulin Rouge! for the first time on my friend’s laptop in our college dorm. I enjoyed the film, and when it was announced that the Broadway adaptation was making its way to TPAC, I got excited. While I didn’t remember many details of the plot, I remembered spectacle, music, and a satisfying mixture of comedy and melodrama. The Broadway show doesn’t disappoint.

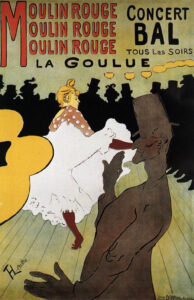

For those unfamiliar with Baz Luhrmann’s film, it’s a 2001 jukebox musical set in Paris at the turn of the 20th century. The Moulin Rouge is a real cabaret (you can visit it today) and the birthplace of the can-can dance. It was in a poor district where wealthy aristocrats could play at slumming it and mix with the bohemian locals. One such local artist was the famous painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who designed posters for the venue, and who features as a character in the story.

The plot is simple: Satine is a courtesan who is the star performer at the financially struggling Moulin Rouge. Christian is new to Paris and hoping to make it as an artist. He quickly falls in with Toulouse-Lautrec and they work on a musical show to pitch to Satine, hoping to get it on the stage of the cabaret. Satine is told by Zidler, the founder of the cabaret, that after her performance that night she is to entertain the Duke of Monroth in her chambers upstairs, and that the great hope is to convince the wealthy aristocrat to provide financial backing to prevent the club from going under. In a fateful miscommunication, Satine thinks that Christian is the duke, and invites him upstairs after the show. In a hilarious scene she tries to seduce him while he’s trying to pitch the musical, and as they’re getting to know each other the real duke shows up at her door. Realizing the mixup, Satine covers for Christian’s presence by pitching the musical to the real duke, and convinces him to back the show. As the story progresses, Satine has to figure out what she wants, choosing between the poor but kind Christian and the selfish Duke who stands as the stereotype of her material ambition.

The Broadway musical has surprisingly little dialogue and is crammed absolutely full of music. The medleys are almost nonstop: pages 28-30 of the program are tightly packed musical credits listing the musical quotes. The music of the film has been updated, altering some of the major moments and adding to many of the minor ones with hits like “All the Single Ladies,” “Rolling in the Deep,” “Bad Romance,” “Chandelier,” and (delightfully) “Fidelity” and “Royals.” This is only naming a few of the recent updates (which even include a Rickroll). Each possible line of dialogue is used to break into song, musical quotes continually riffing off of each other. The frenetic pop music is fun but by the end of the night I felt over-stimulated in a way that even Broadway’s Beetlejuice hadn’t left me. My experience of the music reminded me of the first 55 seconds of this clip from Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid: STEVE MARTIN MAKES COFFEE. I went through phases of being entertained, finding it too much, and being entertained again. My only real musical disappointments in the updated arrangements were that “Roxanne,” the dramatic song of angst, was adapted in a way that felt less impactful than that of the film, and that “Firework” was used for Satine to express her inner conflict; I was tired of that song back in 2010.

The film is set in a cabaret that was the epitome of fin-de-siècle European decadence, and it won an Oscar for its costume design. Not to be outdone, the Broadway adaptation won ten Tony awards, four of which are for costumes, stage, choreography, and lighting design, all of which are fantastic and attention-grabbing. The opening of the musical showcases all of this at once, as we witness the Moulin Rouge’s spectacle: massive setpieces of opulent splendor have lingerie-clad dancers performing high energy sensual movements, while the lighting uses spotlights, silhouettes, and dramatic colors to set everything off. The imagination and skill in accomplishing the intended effect is very impressive.

Moulin Rouge’s cast is somewhat uneven: some actors are surprisingly pitchy or sound like they have been cast for the wrong vocal range, but the standouts are amazing. Christian Douglas plays Christian, and his voice is fantastic: strong, clear, and always in perfect control. While his character isn’t particularly interesting, he gives the role as much personality as possible. Robert Petkoff is the reprobate Zidler, and his dramatic showmanship, heart, and humor make him the most enjoyable character to watch. AK Naderer is Nini, Satine’s friend, and one of the dancers. No matter how crowded the stage, no matter what the choreography was, she always drew our eyes.

I attended the October 9th show. TPAC’s Jackson Theater was packed with people and looked to be almost entirely sold out. Everyone around us was excited for the show and remained fully invested the entire time. They responded to all the musical quotes, laughed at all the jokes, and when a character died at the end the hall was full of sniffles and stifled tears.

The show is full of lights and colors, nonstop music and activity and dancing, and the experience is a lot of fun. I’d recommend it to anyone who enjoyed the movie and to anyone who’s never heard of it: there’s no better setting for a story about live theater than on a Broadway stage.

Moulin Rouge! will be at TPAC until October 20, before moving on to Chattanooga. For tickets and more information, see Moulin Rouge! | TPAC and for more information about the national tour, see US Tour – Home – Moulin Rouge! The Musical.

Cinema in Nashville:

The 2024 International Black Film Festival

The International Black Film Festival (IBFF) held its 19th annual festival this October 2nd-6th. The IBFF is the only African-American established and inspired film festival in the state of Tennessee. Its mission is to “encourage culturally accurate depictions of all people in film with special emphasis on providing a forum of access for underserved and unheard voices as well as to showcase the artistically rich creativity and diversity found around the globe.”

This year’s films certainly fulfilled their mission! The 2024 festival included feature length narrative films and documentaries as well as narrative and documentary shorts. Besides the films, industry panels discussed everything from AI to finance, and networking mixers as well as the awards ceremony made for a full five days. Our journalists were only able to cover a small taste of the many offerings: A Documentary Feature (The Tennessee 11), one collection of Narrative Shorts, and one Narrative Feature (The 6th).

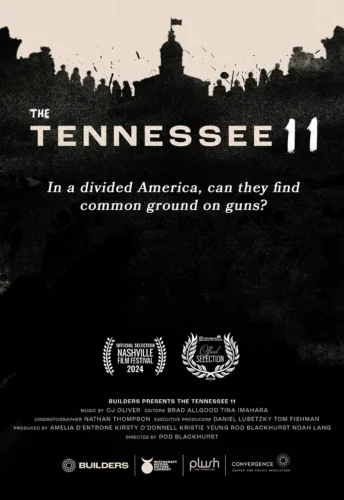

The Tennessee 11 (Review by Y Kendall)

It started with a 911 call. Panic in the voice of a woman reporting a horror. The horror—nearly predictable in twenty-first century America—a school shooting. But this time was different.

The 19th annual International Black Film Festival opened to an undeservedly sparse audience of a few dozen viewers. But the power of the story riveted every witness to this screening. The Tennessee 11, directed by Rod Blackhurst, was supported by Builders Movement, Citizens Solutions, and Convergence: Center for Policy Resolution, non-profit organizations dedicated to building unity in communities. This film originally premiered on September 23, at the Oscar-qualifying 2024 Nashville Film Festival.

In accordance with its advertised tagline, “In a divided America, can they find common ground on guns?” the film tells the story of a community effort bringing together eleven Tennesseans from different walks of life to deal with the issue of gun violence in our state. This came in the wake of the shooting at Covenant School in Nashville, a predominantly white Christian school in the upper-middle class Green Hills neighborhood. The shooter was a white former student who identifies as male.

The Tennessee 11, as they’re now called, comprises one middle school administrator, a high school teacher, a college literature professor, a combat vet who serves as a mental health counselor, a marriage/family therapist, a former State Trooper, a college student, a self-proclaimed “gun advocate,” a community activist who was formerly a gang member, and two pastors, one black and one white. For three days, conflict resolution specialists guided the group to eight consensus proposals that were placed on a website garnering over 30,000 community comments and majority agreement on five of the proposals.

Periodically, words appeared on a textured linen-appearing screen, alternating with scenes of parents and police outside Covenant, scenes of protests within and outside the Tennessee Capitol, the narrative of the eleven citizens willing to work toward change, and screens of cloudy black, white, and gray spills that seemed an apt visual metaphor for the varied points of view.

It would have been quite effective as a test of the group’s effectiveness to have at least a summary of all eight proposals on one of the text screens, because one of the proposals was actually passed into law in April 2024. HB2882/SB2923 is, unsurprisingly, one of the weakest of the proposals, requiring “local education agencies and public charter schools to provide students with age- and grade-appropriate instruction on firearm safety.”

Given the initial intransigence of the “Second Amendment” purists, it’s amazing any agreement was reached. For gun instructor Tim Carroll, even a mention of the term “gun safety” triggers a defensive reaction. Similarly, Jay Zimmerman, the vet counselor, held that owning guns is a “god-given” Constitutional right. Meanwhile Professor Brandi Kellett declared that “the right to carry a gun without a check or a permit infringes on my right to be safe.” Notably, all the pastors and the therapists are male and pro-gun-ownership. One is even an NRA member. But, Ron Johnson, Nashville Community Safety coordinator, whose mother died as collateral gun violence, spoke for all by sagely stating: “There’s nobody who lives in a community that don’t wanna be safe.”

The film’s director and cinematographer effectively used both closeups and panning over the entire group, spaced with poignant vignettes from individual life experiences: college student Jaila Hampton putting flowers for a memorial honoring her dear friend, a young black man dead as collateral damage in a senseless gun incident in Memphis, and vet Jay Zimmerman walking in the woods as he fondly remembers hunting with his grandpa in Elizabethton.

Mark Proctor, a white male with 24 years of Highway Patrol officer experience may have been the glue holding the prospect of success together. The pro-gun faction couldn’t dismiss his law enforcement credentials and his sincerity allowed the other side to put aside their concerns about over-policing and lax public safety to believe in his clear support for sensible legislation.

After the film, there was a brief discussion involving four of the eleven: Kellett, the lit professor who was removed from the Capitol for holding a sign supporting increased gun legislation; Johnson, who coordinates community safety programs; Proctor, the former State Trooper, and William Green, pastor and board member for the IBFF. The discussion was led by Leon Ford, a young wheelchair-bound victim of gun violence resulting from a traffic stop by a member of the Pittsburgh Police Department. Mr Ford, shot five times in a case of mistaken identity, is a mental health ambassador, recognized with President Obama’s 2017 Volunteer Service Award and named in Forbes 2023 “30 under 30.” Notably, none of the strongest “pro-gun advocates” attended the discussion.

Because of content gaps in the film, viewers are left wondering what was left on the cutting-room floor. For example, the film made no reference to the “well-regulated” text of the US Constitution’s oft-mentioned Second Amendment. Post-discussion, I was able to ask Pastor Green if that had ever come up. It had not. The film also made no mention of proper storage of firearms or any parental responsibility if underaged children get their hands on legally owned firearms and committed crimes with them, but Pastor Green assured me that that had been part of the discussion.

Ultimately, The Tennessee 11 tactfully shows the benefit of civil conversations in a free society. Yet Professor Kellett’s words remain true: current Tennessee gun policies are disproportionately weighted toward gun proponents and this is unlikely to change.

Short Suite 2 (Review by Bethany Morgan)

Superman Doesn’t Steal

This short is a slice of life set in the 1970’s in Atlanta during the Atlanta Child Murders. It is based on the writer’s (Tamika Lamison’s) own childhood. It opens with two children discussing superheroes and villains. The older brother, Jackson, explains to his sister, Harriet, that Robin Hood could be viewed as a villain because he stole, but he was actually a hero because he gave to the poor. As the short goes on we see that some people we view as heroes, like police officers, can be villains. Conversely, we see that a father who makes a choice to discipline his son, out of fear rather than anger, is not the villain that he might have appeared to the son in that moment, but a man doing his best to protect his family: a hero. Jordyn McIntosh did a stellar job as Harriet. The story is told from her viewpoint, and I found myself grateful for her curiosity because we see private moments when she peeks into rooms or through windows. Ellis Hobbs IV is wonderful as her older brother: slightly annoyed with his sister at times, and thinking he knows best. The most poignant moment of the film is the mom and dad sitting on the bed after everything is over, crying together. Seeing the vulnerability of the father who has to be strong for his family is beautiful and Tamika Lamison and Mustafa Shakir do a really lovely job. This is a captivating short that you should take the time to watch. Don’t skip the credits; they’re set to Shakir’s song “Black Super Hero:” a throwback to the big beats of the 90’s.

Diamond Mines: The Public Art of Ronald Llewellyn Jones

This documentary showcases the Houston Museum of African American Culture’s choice to commission Ronald Llewellyn Jones to create public art that would continue its efforts to create a sense of empowerment and pride in Houston neighborhoods characterized by segregation and high levels of poverty. John Guess Jr, the director of the film and the CEO of the Houston Museum of African American Culture, reveals an anecdote: he had told Jones that they wouldn’t be seeking permits for the art, only for Jones to reply that he wouldn’t work with permits anyways. He created a beautiful piece made of string, connected to trees and concrete blocks, that resembles a web with geometric shapes, similar to the facets of a diamond. Jones explains how the neighborhood where he placed his work is slowly changing due to gentrification. They come in like the area is a diamond mine, he says, but they view the land as the diamonds, when it’s actually the people that are diamonds. Members of the community were interviewed and spoke about what it meant to them to see such a unique and grand work of art in the middle of their neighborhood. Another clip shows Jones picking up trash in the area. He explains how change can start with just one person and one action: someone will see him pick up trash and decide to do it as well. John Guess Jr points out that Jones’ work is never vandalized, it’s too precious to the community. This was my favorite of the four shorts. Jones’ ability to turn hardships into blessings, and areas of poverty into areas of beauty was truly amazing to behold.

Ghostwriter…

Written, directed, and starring Vonii Bristow, this narrative short tells an important story: what happens to the families of a person that has been killed by police brutality. We have heard the stories of Breonna Taylor, Trayvon Martin, George Floyd and many others. Perhaps we haven’t always considered how these deaths have affected family members or if it’s possible to move on from the grief of a loved one being murdered by someone in a position of power. The short opens with a young boy, Simi, (Terrell Johnson Jr.) asleep. His mother (Rachelle Neal) comes in to read the note that he has left for her on his bedside table. Although she takes the letter with her, the boy wakes up to see it still sitting on the nightstand. We piece together that she has passed away but it isn’t clear until the end when the boy, now grown up, reveals the memory of a policeman pulling the family over and shooting her off camera. There is no clear resolution to the emotional toll that this has taken on the boy and his relationship with his father (Cornelius Muller). While I really loved the idea for this film, some choices didn’t make sense. The person to trigger him (by using the nickname his mother always used for him) is his old therapist, who apparently is dating his father. This is an unnecessary complication. The ending, although depressing, is a good choice, reminding the audience that there is no end to grief and real life doesn’t always have a happy ending.

The Nights of Verona

This narrative short is a contemporary prequel to Romeo and Juliet that follows Mercutio (Jean Elie). He must broker an alliance between his family and the Capulets in order to quell the power of the Montagues, while being terrorized by Queen Mab (Amber Azadi) with visions of his imminent death. The film goes back and forth in time and includes nightmarish hallucinations. It seemed inspired by Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 film Romeo + Juliet with bright colors and an almost frantic pace, although I would describe it as much more gritty and less campy. I admire the boldness of adding to Shakespeare’s play; however, I found the film difficult to follow and lacking substance. Art should have a message of some sort to convey and maybe I need to rewatch this short, because I didn’t get anything out of it, which is frustrating because this is the one I was most looking forward to watching. There are some things that I enjoyed: the costuming by Mieshia Petersen is flawless, the creepy Queen Mab adds the perfect amount of horror, and the all black cast is such a refreshing look at Shakespeare whose plays would have been performed by an all white, male cast when originally produced.

The 6th (Review by G. E. Tipton)

The 6th is a Narrative Feature written, directed, and starred in by local MTSU alum Ricky Burchell. While the IBFF is a welcoming space for first-time filmmakers, Ricky Burchell is hardly new to the scene: his IMDB lists 14 director credits and seven of his films are currently available on Prime Video.

The title of the film refers to the 6th Amendment of the Constitution. For those of you who (like me) can never keep the numbered amendments straight, this is the amendment providing rights to citizens undergoing criminal trial, such as the right to a speedy and public trial, a fair jury, legal representation, the right to know charges, and so on.

The urban drama starts viscerally: nighttime in an alley, one man beats a prone man with a metal pipe. Then we see what happened prior to the brutal event. The man who had been committing the violent act is prominent Atlanta attorney Marcus A. Coles (Burchell) just won a major victory and chooses to take on what at first seems like a simple defense case. Asked by his friend, rapper-producer Feylon X (Lil’ Flip), to defend a cop who claims he’s been framed for stealing evidence, what seemed like a straightforward case begins to spiral out of control: Feylon X is murdered and Coles is called in as a possible suspect. We see the slow corruption of Coles’ already compromised character as he has an affair with a fellow lawyer, attempts to investigate the murder, clashes with police, defends his client, and tries to protect his friends. The 6th’s message is that you are who you surround yourself with. Constantly defending and befriending criminals, Coles admits himself to having changed his ideals, from becoming a lawyer because he believed in truth and justice, to deciding that it’s actually all about winning. While not rated by the Motion Picture Association of America, I’d give this film an unofficial R-rating due to sexual content, profanity, and violence.

The characters are varied: a chauffeur/assistant, reporter, computer hacker, rappers, music moguls, nightclub owners, thugs, and clean and dirty cops. The cast is diverse and avoids any typecasting. Several characters speak Spanish as a first language and my only regret is that a brief scene includes their comic dialog in Spanish but doesn’t provide English subtitles. While not what I’d call an action movie, The 6th does have action scenes: car chases, gun shots, explosions, and murder. Much of the drama is conveyed through conversation and multiple story threads are explored and developed. I appreciated the sense of humor that appeared throughout the film, providing relief to the constantly mounting tension. In one such moment, Coles and his assistant come to their colleague computer hacker for help, and she welcomes them into her office while only wearing a towel. They’re clearly uncomfortable but she’s unfazed and asks them, “Don’t you shower?”

The plot was occasionally confusing, switching from event to event, and leaving some of the character’s actions and motives unclear. Some of the unevenness in the film was explained in the Q&A after the showing, when Burchell said The 6th was originally conceived as a ten part series, but conversations with distributors convinced him to adapt the story to a feature length film. He hopes to complete the story with a sequel, possibly in an episodic series format, which I think would suit his writing.

All the women are talented at their jobs and make sense. This film passes the Bechdel test: two women have a conversation with each other that’s not about a man. The only portion that cracked me up and felt a little man-writing-women was that no matter how late or unexpectedly Coles shows up at their houses, the women (with the exception of the computer hacker) are always wearing lingerie with full makeup and carefully styled hair.

While set in Atlanta, The 6th was shot in the Murfreesboro area. At the Q&A Burchell stated that the film was shot on a low budget, and the cast backed him up on this, calling the effort a family endeavor and cheerfully mentioning how they all played many roles behind the scenes: acting, carrying sandbags, changing lights and working long days. While this budget constraint is occasionally noticeable during some special effects (explosions and some gunfire), I think their hard work and good management of the budget is successful. The costumes match each character and the sets are good, with a variety of locations and plenty of extras.

Some of the shots, especially of car chases, are of impressive quality. To suit my personal taste, shaky-cam is almost completely avoided, except for a few brief moments where it fits the nature of the scene.

The casting is good, each actor enjoying their role and fitting the requirements of their character. As of publication, the full cast and crew credits have not been released, so I cannot give credit to everyone who deserves it. I can say that I enjoyed the haughty-eyed attitude of Hannah Brake, and Chanelle de Lau’s seeming straightforwardness. This film engaged its audience at the IBFF and I hope the cast and crew will continue to make films, develop the local film industry, and create more entertainment for us Tennesseans!

To learn more about the IBFF or to join their mailing list so you don’t miss the festival next year, see International Black Film Festival. Each year we work to expand our coverage of Nashville’s film festivals, and we look forward to covering and celebrating their 20th annual season next year!

The MCR Interview:

Actress Lisa Arrindell and ‘Jubilee’

Actress Lisa Arrindell speaks with MCR journalist Andrew Davis on Tazwell Thompson’s Opera ‘Jubilee’ premiering at the Seattle Opera this month. They discuss the history of the Jubilee Ensemble and experience of participating in the production. (please like, subscribe, and share!):