Nuevo de Music City

No Es Danza Macabra, Es Ballet Con Identidad

(English Version here)

Cuán afortunados son aquellos en quienes sus recuerdos se revelan con nitidez y movimiento. Aún más afortunado es el que es capaz de replicarlos para que permanezcan en la memoria colectiva. Mi maestro de guitarra me decía “Si lograste ver dos ligeras bailarinas danzar, mi interpretación habrá cumplido su propósito.” Ese mismo propósito que inspira los trazos de un artista y los versos del compositor. Ese deseo ambicioso de hacer palpable la imaginación. Y esas bailarinas no son solo un espectro de su creador; su danza es recíproca y transforma la materialidad en movimiento. Los pasos convierten la retórica en un objeto tridimensional, más sin embargo, el espectador conserva la autonomía en su interpretación. En ese instante la remembranza cumple un ciclo impregnando la escena con la historia de cada individuo. Tras bambalinas, sobre el escenario y en las butacas, se ha bordado un tapiz en homenaje a la memoria. Lúcido y lleno de flores como los trajes chiapanecos.

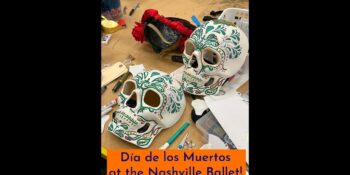

Desde los prolijos arabescos de las máscaras hasta el sentido altar como centro de la escenografía, Día De Los Muertos es un montaje que se destaca por el cuidado de los detalles. La esencia de esta tradición narrada a través de la inspiración artística de Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Carlos Chávez y Lola Álvarez Bravo inicia como un gran acierto en la creación del guion. La incorporación de elementos folklóricos como los mariachis y los alebrijes junto con las figuras místicas de La Catrina y La Bruja, le dieron un toque mágico a la historia. Maria Konrad y el equipo artístico y de producción honraron con elegancia y emotividad la cultura mexicana.

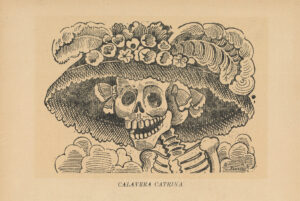

Se me escaparán muchos elementos, así que ya pueden hacerse una idea de la abundancia creativa en este show. Comenzaré por La Catrina al ser uno de los ejes principales no solo en el montaje sino en su significado para la tradición mexicana. Si bien este personaje está inspirado en la versión de Diego Rivera en su célebre obra “Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central”, la figura se basa en La Calavera Garbancera del también artista mexicano José Guadalupe Posada. La ilustración es una crítica a los indígenas vendedores de garbanzo que menospreciaban sus orígenes y aparentaban una posición social superior. “En los huesos, pero con sombrero francés con plumas de avestruz” la describió Posada. En la obra de Rivera, el personaje aparece de cuerpo completo con un traje acorde al característico sombrero, pero con detalles mesoamericanos como la bufanda en forma de Quetzalcóatl (serpiente emplumada). Rivera le da un lugar especial entre las 150 figuras que se incluyeron en esta obra magna. La Catrina, como el artista la renombró, representa a cada ser humano que, despojado de su apariencia, comparte con sus semejantes la misma estructura y el mismo final.

Entre los diferentes estilos de danza que se incluyeron en el montaje, La Catrina tomó ventaja de la técnica de punta del ballet clásico para representar su naturaleza estilizada. Además de eso, sus pasos eran lo suficientemente sonoros para reforzar la cualidad “idiofónica” de sus huesos. El personaje aparece estampado en un lienzo durante el proceso de su creación en lo que podría imaginarse como el estudio de Rivera. Allí el pintor comparte su pasión artística con Frida Kahlo mientras da unas últimas pinceladas hasta convertir la figura en una bailarina que se une con sus movimientos al romanticismo de la escena.

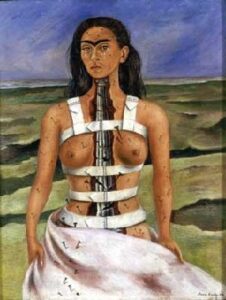

El traje de Frida Kahlo estuvo también inspirado en una pieza de arte, su autorretrato “La columna rota”. Esta pintura representa la fortaleza de su cuerpo y de su alma al mantenerse en pie a pesar de haber sufrido un accidente prácticamente mortal. Las flores bordadas en su falda fueron replicadas en el traje de Rivera reforzando el vínculo de la pareja. La interacción de sus movimientos era cómplice y prolongada, fluyendo en perfecta armonía. En las siguientes escenas se une el compositor Carlos Chávez con un aire de feria, movimientos torpes y zafados que me recordaron al reconocido actor de comedia Cantinflas. La fotógrafa Lola Álvarez Bravo, en contraposición, es ligera, flexible y llena cada espacio del escenario mientras obtiene las mejores capturas con su cámara. A esta celebración de la vida y de la amistad entre los artistas, se une el grupo de mariachis y las bailarinas folklóricas. Los pasos son una mixtura de jarabe tapatío y danza moderna.

La selección musical de este ballet es otro gran acierto; incorpora la música tradicional y mariachi con lapsos de electrónica. El paisaje sonoro se torna también cinematográfico con las propuestas modernas de Gustavo Santaolalla y el dueto de guitarristas Rodrigo y Gabriela. El plano terrenal parece ser lo suficientemente fantástico, sin embargo, el altar en la escenografía actúa como el portal que nos guiará hacia el mundo de la eternidad. Encontré muy hermosa la sección en la que los bailarines representan cada uno de los gustos de la persona que se está honrando. Uno de ellos ejecuta hábiles ‘toques’ con el balón de fútbol para luego sumarlo a las ofrendas del altar. Entre estos objetos se encuentran también los ‘alebrijes’, guardianes espirituales de naturaleza zoomorfa cuyo propósito es el de guiar la travesía del alma. Estos seres mágicos se transforman en bailarines de colores y personalidades diversas, representando las cualidades que hacen único e irrepetible a cada mortal.

En unión con la celebración del Día de Los Muertos y la música se engendra el último personaje del elenco, La Bruja. La canción en son popular jarocho y que lleva el mismo nombre, se ha convertido en el himno de esta fiesta popular. La letra se inspira en la leyenda de una seductora mujer que preserva su corporeidad bebiendo sangre de niños y de adultos. El clímax del ballet se consolida en esta escena donde cada uno de los personajes interactúa con La Bruja y la subjetividad de la muerte. La escenografía se torna oscura y las faldas tradicionales emanan luces de colores consiguiendo un efecto supremo con los movimientos de la danza. El traje de La Bruja se enciende también, y cuando la bailarina extiende el amplio tamaño de la falda se revela un brillante cúmulo de estrellas. Este momento de fantasía y emotividad captura ingeniosamente la noche del primero de noviembre en el que las calles se revisten de candelas.

El montaje concluye con un racimo de voces superpuestas que mencionan los nombres y el vínculo con aquellos seres que permanecen en la memoria de cada persona. Los bailarines van dando fin a sus movimientos mientras se ubican en una especie de retrato que evoca nuevamente la obra muralista de Diego Rivera. Este cuadro final no se compone solamente por los artistas en escena, sino por artesanos, músicos, diseñadores y técnicos de una creatividad insaciable y un compromiso con el arte, la cultura y la remembranza humana como esencia de nuestra existencia.

From Our Far-flung Correspondents Series:

Jubilee the Opera

Jubilee the Opera tells the rich history and story of the original Fisk Jubilee Singers. From the conception of the group to their tours across the globe to save their institution from financial ruin, the opera shows the viewer how black students from Nashville, Tennessee, triumphed through trials and tribulations, during the era of reconstruction.

There was a minimalist approach to staging and costumes. This approach not only allows the viewer to focus on the story, but it also foreshadows that their greatest possessions were not materials. Rather it was their relationship to their beautiful melodies. Tazewell Thompson, the director, did a wonderful job intertwining the concert spiritual into the storyline of the opera.

Technically, this body of work was presented like in opera. However, there were moments where it felt as if I was watching a musical. The role of Ella Sheppard, which was portrayed beautifully by Lisa Arrindell, also plays a southern white women, Queen Victoria, and George L. White. As these characters are introduced in the story they are speaking, and the ensemble is reacting. (See interview here) Historically, in opera if the librettist wants to bring out words they use recitatives. Understanding the backgrounds of Tazewell Thompson and Lisa Arrindell, I believe that for this body of work, they made the correct stylistic choice.

It was rather refreshing to see how the humanity of each individual was portrayed. Tazewell Thompson developed the plot of the story by introducing a love affair between two of the singers. While it did intensify the drama of the story line, it seemed misplaced due to a lack of a resolution. Understanding Ella Sheppard’s role with the ensemble, I wish I would have since her developed more. Taze did a wonderful a portraying her as a mother figure and educator, however there were time in which she accompanied the group on piano.

In telling the story of the original Fisk Jubilee Singers, Tazewell Thompson and the entire cast did a wonderful job of introducing the world to one of Nashville’s gems. This body of work is imperative in the rejuvenation and continuation of canon of concert spirituals.

From the Circle Players

For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf

Ntozake Shange’s acclaimed 1976 choreopoem For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf opened Circle Players’ 75th season. Middle Tennessee’s oldest non-profit community theatre group is committed to inclusivity and voicing underrepresented stories.

I attended the October 11th showing, and Tosha Marie, the president of the Board of Directors for Circle Players (as well as producer, choreographer & costume designer of the play) welcomed the audience at the entrance of the theater with a tissue box, hinting at the tear-jerker nature of the play. In an extensive, carefully put together 16-page program that the audience could gain access to via a QR code, she writes:

“This season, we aim to create a space for dialogue and reflection, inviting you to join us in this important work. As we celebrate 75 years of storytelling, we are grateful for your support and engagement. Together, we can create a vibrant theater community that honors our past while looking forward to a more inclusive future.”

Ntozake Shange’s very personal tale For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf resonated with one of Nashville’s most acclaimed and brave theater directors, Cynthia Harris, who “continuously creates and performs works that capture the experiences of Black women and girls. Her preferred format is the choreopoem, which she views as a culturally specific form of performance and audience engagement, based on the work of Ntozake Shange, to authentically express the personal and social experience of Black women.”

For this staging, Harris got her inspiration and directorial vision from her childhood memories of her mother and her four aunts sitting around the kitchen table in the late 60s while lending eyes, ears, strength, and wisdom to each other’s struggles. According to Harris, this experience can and should expand beyond blood sisters, into what she calls “sister-friends.” Thus the director not only inherits Shange’s artistic expression through her preferred format of choreopoem, but also the feminist philosophy and approach to life. Interestingly enough, Harris does not borrow the dance aspect, one of the main elements of Shange’s choreopoem, although she endorses the poetic monologues and music. This absence can be read as the director’s darker vision of the condition of black and brown women: united in their voices but not fully liberated through their individual bodily freedoms of expression.

In an Airbnb stage setting (designed by Henry Jones), the walls of which are filled with portraits of powerful and resilient black women, Harris creates a rainbow of “7 sisters reuniting in response to intimate partner violence. Their stories are shared as if they were medicine to each other, helping them to heal together through bringing up their unconditional love and support for each other. These women serve as sacred witnesses to each other’s healing and transformation.”

In an Airbnb stage setting (designed by Henry Jones), the walls of which are filled with portraits of powerful and resilient black women, Harris creates a rainbow of “7 sisters reuniting in response to intimate partner violence. Their stories are shared as if they were medicine to each other, helping them to heal together through bringing up their unconditional love and support for each other. These women serve as sacred witnesses to each other’s healing and transformation.”

The story of the play consists of women, sisters, and sister-friends who, beginning with the youngest one, feel safe to open up and connect on a natural and supernatural level. They transcend through the experiences of mythical heroines and goddesses, all having one thing in common: the beauty and burden of womanhood, the ill treatment, despotism and exploitation that still reigns in a society rendering her as an unequal member. Thus, through any layer of discrimination on the basis of identity politics, it was very easy to feel empathy with the stories that were being unfolded on stage.

In terms of mise-en-scène, every corner of the stage was fully utilized. When one of the women shared her story, the others were attentively listening, surrounding her from various angles. There were also beautiful moments of gathering in smaller groups to converge and connect. Although the performance didn’t directly invite this, the audience was often communicating their empathy, encouragement, and dismay directly, which created a warm homey atmosphere.

Among the actresses, Kristian Hardy as Green especially stood out for her stoic presence in silence, often listening to the other’s stories with full attention. For her last fragment, Nina Hibbler-Webster as Rea took everyone’s breath away.

One major hiccup that was a distraction and worked rather against the other elements of the staging was the bad wireless microphone connection which almost sporadically switched between the actresses’ natural and amplified voices. The small theater setting would have functioned without microphones just as well, elevating the intimacy between the performers and the audience.

One major hiccup that was a distraction and worked rather against the other elements of the staging was the bad wireless microphone connection which almost sporadically switched between the actresses’ natural and amplified voices. The small theater setting would have functioned without microphones just as well, elevating the intimacy between the performers and the audience.

During the post premiere talk, in the presence of the seven actresses, Harris spoke of the audition, the rehearsals and of giving space to them to both find their inner voices and connection with their characters, as well as to form a bond with their sister-friends to grow in harmony while embracing their diversities in appearance, style, approaches to life and challenges they face.

By the edge of the blade, both the choreopoem and the staging carried the danger of villainizing all men, particularly the black cis men, until the last monologue where the brutal actions of the perpetrator became related to his loss of sensitivity and the trauma from serving in the army and experiencing the brutality of war, thus raising the issue to a bigger picture, that of the systemic instrumentalization and oppression.

Overall, the performance grew in me as it unfolded the layers of these seven unique women, representing a rainbow, a grain of hope, an aspiration to dream for a better future, only if in that dream we are all equal, while unique and understanding the importance of coexisting as a way of fulfilling one another.

This production’s run is over, but Circle Players’ 75th season continues with And the World Goes Round in the winter. For more information, see Circle Players.

At the Schermerhorn

NSO’s One Program in Three Mediums – Opera, Orchestra, and Ballet

The Nashville Symphony and Maestro Giancarlo Guerrero took audiences to the opera house, the concert hall, and even the ballet with the program presented October 17-19. Featuring the artistry of violin soloist Gil Shaham, this program was situated between a performance the previous weekend of Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 8, nos. 1-4 and Gloria, R. 589, and a special event accompanying the Tower of Power this upcoming week. Such variety of programming and regular performances are two of the many strengths that have come to be expected of this organization.

Composed in 1869, the Overture to La forze del destino has cemented itself as a favorite from the pit of opera houses and on stage in concert halls alike. The libretto depicts the consequences of an ill-fated love story, or, in other words, a typical Nineteenth Century opera. A respectfully full house welcomed both Concertmaster Peter Otto and Music Director Guerrero to the stage, after which the opening chords from Giuseppe Verdi’s score quickly sounded.

Perhaps more caffeinated than some interpretations, Guerrero propelled the three opening chords from an impeccably balanced brass and bassoon sections twice, not allowing the first iteration to completely dissipate throughout Laura Turner Concert Hall before inviting the music to continue. Chandler Currier, the new principal tubist and a Middle Tennessee native, is to be credited for playing a cimbasso for this opening piece. With a forward-facing bell and predominantly cylindrical bore, the cimbasso creates a bass sound that can blend with the trombone section even better than can the tuba. Historically, this instrument was commonly used to perform late Romantic Italian opera, so much so that it has even been referred to as the ‘trombone basso Verdi.’

Equally impressive to the robust opening presented by the brass and bassoon sections was the Nashville Symphony’s dynamic range made available throughout Verdi’s score, particularly the softer end of the spectrum. In a society where loud and bold tends to occupy headline real estate, the Nashville Symphony’s willingness to take advantage of opportunities to offer such nuance should be both acknowledged and encouraged.

Having just performed Ludwig van Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 61 last season, violin soloist Gil Shaham is becoming a perennial highlight for Nashville Symphony audiences. After an extended tuning session backstage, Shaham accepted applause with a humbled grace that seemed to have won him the favor of both members of the Nashville Symphony and its audience – all realities that occurred last season, too. This program featured Mason Bates’ Nomad Concerto, with the added feature of a live recording project expected to be commercially released upon completion.

Along with the Philadelphia Orchestra and San Diego Symphony, the Nashville Symphony is a consortium partner that helped initiate the creation of this work. Receiving its premiere performance with Yannick Nézet-Séguin conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra in January 2024, this piece is the second violin concerto composed by Mason Bates, who offers the following program note:

Nomad Concerto explores the mysterious and soulful music of the wanderer.

Envisioned to showcase the legendary Old World sound of Gil Shaham, the concerto is informed by a diverse range of traveling cultures from Eastern Europe to the Middle East. In the same way that nomadic musics have continually reimagined themselves, the many styles informing the concerto are swirled together into a unique soundworld.

The concerto’s opening movement imagines an old balloon seller wandering through a village as he sings a doleful tune, which is gradually picked up by the villagers. The music draws from a variety of elements of the European Roma, with the soloist sometimes using a strumming pizzicato effect suggestive of mandolin. The movement is followed by the short, scherzo-like ‘magician at the bazaar’ showcasing quicksilver violin figuration that the orchestra transforms into shimmering and gossamer textures.

Over haunting orchestral expanses depicting the vast deserts of the Middle East, the Jewish folk tune “Ani Ma’amin” unfolds in “Desert vision: oasis.” The movement’s heaviness temporarily brightens at the vision of a sparkling oasis. A propulsive finale is animated by the ‘minor swing’ of 1930s jazz clubs, as epitomized by the legendary Django Reinhardt of the ‘manouche’ clan.

Bates has completed residencies with leading orchestral institutions throughout the United State of America – the San Francisco Symphony, National Symphony, and the Chicago Symphony, among others – as well as spinning numerous sets as a dj. All of these influences have been filtered through the composer’s perspective to create a work that, at times, presents quite cinematically, on occasion offers a hip and urban vibe, while still at other times depicts a pastoral expansiveness that calms. Shaham is called to use various string techniques, including a glassy ponticello bowing, as well as bowing while simultaneously using pizzicato with his non-bow hand. Bates’ Nomad Concerto is an intriguing composition that was executed convincingly by both soloist and orchestra. Mason Bates was welcomed to the stage to receive multiple rounds of well-earned applause, before joining the audience to experience the second half of the concert.

After intermission, Igor Stravinsky’s original 1909-1910 full ballet score for The Firebird completed the program. Lasting about fifty minutes, it is more common for the twenty-two minute Suite from The Firebird to be programmed instead. Offering the entire score affords one the opportunity to hear gestures evolve and the drama they depict to develop and subside. However, without the dance component, sections of the music felt stagnate and unnecessary for the concert hall alone. Furthermore, if dancers were involved, Maestro Guerrero forced tempi that, on occasion, felt frantic and presumably an unfit challenge for choreography.

Regardless, this assumed ‘pet project’ was well received and impeccably performed. Despite many key players of the ensemble executing solo passages with such spirit, or soul as the situation aligned, members of the Nashville Symphony stood together without any individual bows initiated from the podium. Special congratulations should have gone to the woodwind block of the orchestra who brilliantly gave flight to the Firebird, and to principal bassoonist, Julia Harguindey, who offered a “Lullaby” that mesmerized.

Nashville Symphony President and CEO, Alan D. Valentine, needs credit for establishing a culture that welcomes patrons in suits and jeans all the same. Art is often a reflection or a reaction to the context in which it was created. Even without serious study of the medium, music’s power is universal, being felt by academics and amateurs. Nashvillians are urged to open themselves to experience live classical music by an ensemble that has removed many of the barriers once thought to pretentiously protect this magic. Giancarlo Guerrero has built your Nashville Symphony with an artistic prowess that doesn’t need an oceanic coast to prove worthy of receiving accolade or your attention. If you are not patroning the Schermerhorn Symphony Center you are missing out!

The MCR Interview

Nashville Ballet NB2 Director Maria Konrad on Dia de los Muertos

Angelica Trujillo conducts an interview that serves as a wonderful introduction to the new director of Nashville Ballet’s NB2 Troupe, Maria Konrad, as well as a thorough introduction to the ideas and aesthetics behind Konrad’s choreography for this world premiere of Día de los Muertos. Issues in presenting and mingling ballet, contemporary dance, folkloric dance and movement onstage are discussed. Dancer Nicole Bustamante answers a few questions on her own perspective of the work. The basic narrative of the ballet, including the primary characters, Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Carlos Chavez, and Lola Avarez Bravo. Linares’ Alebrijes, their appearance and creation (with 3d printing) for the performance are discussed. Like, Share and Subscribe!

Moulin Rouge! The Musical

Ten years ago I saw Moulin Rouge! for the first time on my friend’s laptop in our college dorm. I enjoyed the film, and when it was announced that the Broadway adaptation was making its way to TPAC, I got excited. While I didn’t remember many details of the plot, I remembered spectacle, music, and a satisfying mixture of comedy and melodrama. The Broadway show doesn’t disappoint.

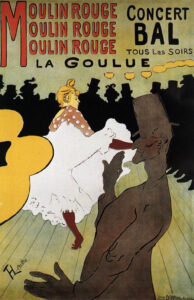

For those unfamiliar with Baz Luhrmann’s film, it’s a 2001 jukebox musical set in Paris at the turn of the 20th century. The Moulin Rouge is a real cabaret (you can visit it today) and the birthplace of the can-can dance. It was in a poor district where wealthy aristocrats could play at slumming it and mix with the bohemian locals. One such local artist was the famous painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who designed posters for the venue, and who features as a character in the story.

The plot is simple: Satine is a courtesan who is the star performer at the financially struggling Moulin Rouge. Christian is new to Paris and hoping to make it as an artist. He quickly falls in with Toulouse-Lautrec and they work on a musical show to pitch to Satine, hoping to get it on the stage of the cabaret. Satine is told by Zidler, the founder of the cabaret, that after her performance that night she is to entertain the Duke of Monroth in her chambers upstairs, and that the great hope is to convince the wealthy aristocrat to provide financial backing to prevent the club from going under. In a fateful miscommunication, Satine thinks that Christian is the duke, and invites him upstairs after the show. In a hilarious scene she tries to seduce him while he’s trying to pitch the musical, and as they’re getting to know each other the real duke shows up at her door. Realizing the mixup, Satine covers for Christian’s presence by pitching the musical to the real duke, and convinces him to back the show. As the story progresses, Satine has to figure out what she wants, choosing between the poor but kind Christian and the selfish Duke who stands as the stereotype of her material ambition.

The Broadway musical has surprisingly little dialogue and is crammed absolutely full of music. The medleys are almost nonstop: pages 28-30 of the program are tightly packed musical credits listing the musical quotes. The music of the film has been updated, altering some of the major moments and adding to many of the minor ones with hits like “All the Single Ladies,” “Rolling in the Deep,” “Bad Romance,” “Chandelier,” and (delightfully) “Fidelity” and “Royals.” This is only naming a few of the recent updates (which even include a Rickroll). Each possible line of dialogue is used to break into song, musical quotes continually riffing off of each other. The frenetic pop music is fun but by the end of the night I felt over-stimulated in a way that even Broadway’s Beetlejuice hadn’t left me. My experience of the music reminded me of the first 55 seconds of this clip from Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid: STEVE MARTIN MAKES COFFEE. I went through phases of being entertained, finding it too much, and being entertained again. My only real musical disappointments in the updated arrangements were that “Roxanne,” the dramatic song of angst, was adapted in a way that felt less impactful than that of the film, and that “Firework” was used for Satine to express her inner conflict; I was tired of that song back in 2010.

The film is set in a cabaret that was the epitome of fin-de-siècle European decadence, and it won an Oscar for its costume design. Not to be outdone, the Broadway adaptation won ten Tony awards, four of which are for costumes, stage, choreography, and lighting design, all of which are fantastic and attention-grabbing. The opening of the musical showcases all of this at once, as we witness the Moulin Rouge’s spectacle: massive setpieces of opulent splendor have lingerie-clad dancers performing high energy sensual movements, while the lighting uses spotlights, silhouettes, and dramatic colors to set everything off. The imagination and skill in accomplishing the intended effect is very impressive.

Moulin Rouge’s cast is somewhat uneven: some actors are surprisingly pitchy or sound like they have been cast for the wrong vocal range, but the standouts are amazing. Christian Douglas plays Christian, and his voice is fantastic: strong, clear, and always in perfect control. While his character isn’t particularly interesting, he gives the role as much personality as possible. Robert Petkoff is the reprobate Zidler, and his dramatic showmanship, heart, and humor make him the most enjoyable character to watch. AK Naderer is Nini, Satine’s friend, and one of the dancers. No matter how crowded the stage, no matter what the choreography was, she always drew our eyes.

I attended the October 9th show. TPAC’s Jackson Theater was packed with people and looked to be almost entirely sold out. Everyone around us was excited for the show and remained fully invested the entire time. They responded to all the musical quotes, laughed at all the jokes, and when a character died at the end the hall was full of sniffles and stifled tears.

The show is full of lights and colors, nonstop music and activity and dancing, and the experience is a lot of fun. I’d recommend it to anyone who enjoyed the movie and to anyone who’s never heard of it: there’s no better setting for a story about live theater than on a Broadway stage.

Moulin Rouge! will be at TPAC until October 20, before moving on to Chattanooga. For tickets and more information, see Moulin Rouge! | TPAC and for more information about the national tour, see US Tour – Home – Moulin Rouge! The Musical.