Peter Pan: Neverland in Nashville

Peter Pan has a more varied origin story than I had imagined. The Scottish author J. M. Barrie told stories of a flying baby to family friends with five boys (for whom he became a co-guardian after the deaths of their parents). This character then appeared in several chapters in his episodic 1902 novel The Little White Bird, this Peter Pan being an infant who flies with fairies in Kensington Gardens. Two years later he wrote the stage play Peter Pan: Or, the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up. In 1911, Barrie adapted the story into the novel. The copyrights to the character Peter Pan were later gifted by Barrie to the Great Ormond Street Hospital, the UK’s leading children’s hospital. Since then there have been numerous adaptations: most of us have seen the Disney animation, the odd-but-fun Hook, my personal favorite version from 2003, or one of the many others. While Barrie’s original play is rarely performed, the 1954 Broadway musical adaptation is the most popular live version in the US. Successful on the stage and in later adaptations on television, Peter Pan: The Broadway Musical began its North American tour in 2024 with a rewritten book by Larissa FastHorse, and came to TPAC early this January.

I won’t give a summary of the plot because it’s so familiar and accessible. The story is strange and violent (which explains its perineal appeal to children), and this adaptation retains the strangeness and violence, with multiple kidnappings, attempted poisonings, sword fights, and a crocodile. There is no dog Nana, which might leave some disappointed, but I can’t blame the show for wanting to avoid the difficulties of a live animal on stage.

I haven’t seen this 1954 Broadway play’s original portrayal of Native Americans, but judging by the Disney animation’s version from the same decade, it probably needed serious improvement. Native American playwright Larissa FastHorse’s updated book certainly avoids racist tropes, and Tiger Lily has some additional lines explaining her people’s presence on the island as a deliberate preservation of their culture, although much detail about their original arrival or future plans isn’t provided, making the addition feel a little underdeveloped. This updated version is set in modern times, which feels unnecessary since most of the play is spent in Neverland. The modernity is also briefly heavy-handed: as the play begins Wendy is trying to record herself doing a viral dance and she mentions becoming an influencer to help pay for medical school. The babysitter watching the kids is screen-obsessed, and while the humor based on her is funny enough, these additions feel tacked-on and ultimately add nothing. Kids don’t need references to screens to empathise with children running away to fly and battle pirates. Wendy’s new ambition of becoming a surgeon changes nothing in her character and ends up only as an aspirational aside: she shows no surprise, only enthusiasm, when Peter needs her help reattaching his shadow, or using fairy dust to fly. These modern additions are only at the beginning of the show, and the rest of the play remains the charming story we’re familiar with.

The music in the show isn’t particularly memorable: imagine your typical 1950’s Broadway music and you’ve got it. But the songs are enjoyable, upbeat, fun, and allow for comic choreography. Captain Hook has multiple villain songs and the show avoids the sin of show-halting ballads. The live music is excellent under conductor Jonathan Marro. Tinker Bell is my favorite part of the music; her voice is played by a twinkling celesta (or the electronic equivalent), which allows for a surprising amount of attitude. The fairy isn’t played by any cast member, but is a tiny bright light which moves around the stage in impressively timed choreography: strung on wires, then whisked from Peter’s hands to Wendy’s, then into a box, and so on. This technical skill looks effortless.

My only complaint in the special effects is that the crocodile is slightly disappointing. A person in a suit, it only crawls around the stage slowly. Its style doesn’t match the rest of the scenery and looks unfinished and low-budget compared to the high quality of the other costumes.

Another aspect of the staging I really enjoyed is Peter’s shadow. There’s a whole bit during “I Gotta Crow” where his shadow stops doing the correct choreography and dances by itself. Children will find that cleverly done projection to be absolutely magical. The wires for flying are excellent as well: the children are all impressively plausible and graceful as they fly about the stage leaving London for Neverland. The backdrop is a screen, and for part of their flight they turn their backs to us and the screen whooshes through the city as they turn and dive accordingly.

The screen is used well almost the whole time, with realistic or stylized backdrops (depending on whether they’re in London or Neverland), and a few appearances of Peter Pan when he’s darting around the stage, confusing Captain Hook with his vocal mimickry. There is one jarring moment at the end, when for absolutely no reason the moon expands, grows a mouth, moves to the center of the screen, and agrees with what the characters are already saying in a goofy male voice before returning to the sky. This Annoying Orange moment probably intends to capture youthful meme energy, but instead it is obnoxious.

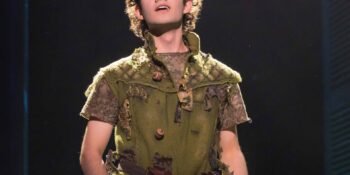

Peter Pan has historically been played by women on the stage. There are many obvious benefits to this: all the dependability and skill of an adult performer, no sudden growth-spurts or voice changes, and so forth. However, having grown up watching talented child actors in movies, seeing an adult woman pretend to be a prepubescent boy is rather off-putting, even in the unreality of live theater. This production is aware of this and cast Nolan Almeida as Peter Pan. He does a marvelous job. A senior in high school, he has a light frame and his well-designed costume makes him look extra boyish. His voice is excellent and he portrays the character with spirited and perfectly-measured petulant childishness as he gracefully flies around the stage.

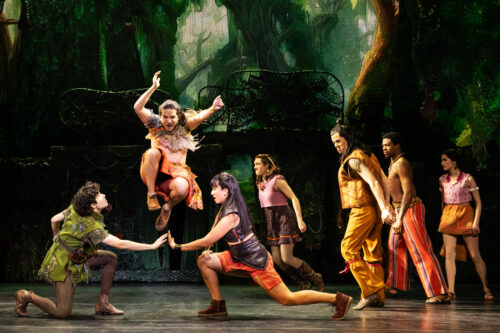

Hawa Kamara is a very sweet Wendy, and reminded me how underrated Wendy is as a character: how often do you have a kind, adventurous, responsible protagonist in such a wild story? Kurt Perry is a funny and unthreatening Smee; by the end of the show you’re convinced he joined the pirate crew entirely by accident. Cody Garcia is Mr. Darling/Captain Hook, and plays the role with proper piratical flourish and comedic drama. Wendy’s brothers and the Lost Boys are cute and charming. Everyone sings with talent and skill. The entire cast meshes well and they look like they’re having fun on stage, fulfilling the promise of Peter Pan, which is to be a delightful dramatization of childhood fantasies.

I attended the Tuesday, January 7th show, and Jackson Hall was packed, families everywhere (most of the performances were almost entirely sold out). The children especially seemed to enjoy it. When Tinker Bell was dying of poison and Peter Pan asked the audience, “Do you believe in fairies?” A little boy a row or two behind me answered “Yes.” With children on stage, a familiar story, magical special effects, and the whole show lasting less than two-and-a-half hours with an intermission, this is the perfect show to introduce children to live theater.

While their run at TPAC is over, you can find more information about the tour at Tour Dates – Peter Pan.

The MCR Interview

Pianist Susan Yang and Her Upcoming Performance with the Nashville Symphony

Music City Review Journalist Brady Hammond speaks with Susan Yang on learning, teaching and playing the piano. Her strategies for practicing and the differences between performing a concerto, in a chamber group and solo recital. In the second half of the interview they discuss her upcoming appearance with the Nashville Symphony for their Second Annual Lunar New Year concert including the history, character and style of the work she is performing, Xian Xinghai’s Yellow River Concerto.

Over in OZ:

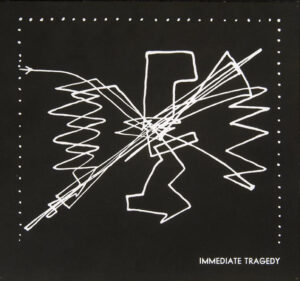

Symphony of Rats by The Wooster Group reaffirms the Nashvillian thirst for unconventional stage work

A home committed to international contemporary and experimental stage work; last weekend OZ Arts hosted the first ever staging of The Wooster Group’s productions in the south of the U.S. with Symphony of Rats.

Why is this monumental? The Wooster Group, a theater company based in New York City, can easily be named as the trailblazers of the avant-garde theater not only in the country but wider. Despite a few local endeavors to bring to the fore speculative approaches to experimental theater, most of which pass through the filter of Kindling Arts Festival once a year, Nashville doesn’t get much exposure to theater or performance works that challenge the normative forms. Most likely due to a mixture of good marketing efforts and a thirsty audience for unconventional performances, the tickets for the first two showings of Symphony of Rats were sold out. As it should be!

The Wooster Group is an invaluable asset worth being studied with awe, not only for their advancement and novices in experimental theater and performance, but for also stoically operating through the winds of socio-political climates that have affected the (lack of) financial support to arts. Over a period of almost half a century (since 1975), they have maintained and refined their collective artistic voice, reimagined classical works, from Phaedra by Jean Racine to The Crucible by Arthur Miller and have become kick starters for the careers of many renown stage and movie artists, including Willem Dafoe who was a founding member, Frances McDormand, and Steve Buscemi, to mention a few. What’s exemplary about The Wooster Group is also how carefully they document their scope of operation, an incredible archive of which can be found on their website.

Staged by the director of the ensemble since its inception, Elizabeth LeCompte and co-founder and performer Kate Valk, Symphony of Rats was first produced at The Performing Garage in 1988, directed by Richard Foreman, the acclaimed American avant-garde playwright and the founder of the Ontological-Hysteric Theater who also wrote the play. It is not easy to speak about the narrative of Symphony of Rats because Foreman isn’t interested in clear meanings, and neither is The Wooster Group. Both pairs are keener on subverting narratives and freeing the audiences from constraints of logical denotations. In a broad premise, the President of the United States (played by Ari Fliakos) takes a pill which helps him receive messages from a different dimension. Whether this is outer space, a moronic or higher state of vindication or the depths of the hallucinatory imagination, it never becomes clear nor is the purpose of the play and the restaging.

The president’s aides (played by Niall Cunningham and Andrew Maillet) or as Valk put it, his “otherworldly looking stagehands” do everything possible to assist the president in reaching this obscure realm. Aside from the aides, there are three other characters on stage: I’ll interpret them as ‘the lab rat’ (played by Jim Fletcher), ‘the voice of clarity or reason’ (played by Guillermo Resto) and ‘the stage bot’ (played by Michaela Murphy) who is also the Assistant Director and the Stage Manager of the performance. The stage design which contains many props that according to LeCompte have been reused from previous performances, not only due to lack of funding but also as an initiative to Reduce-Reuse-Recycle as well as costumes (designed by Antonia Belt) resemble a messy transcendental laboratory with homoerotic features. What adds contrast and humor to the chaotic action on stage are the unambiguous and clear-cut sound cues (sound design/music by Eric Sluyter) and the light nucleuses (designed by Toni-award winning Jennifer Tipton and Evan Anderson), thus comprehensively granting the performance a satisfying equilibrium.

During the post premiere day conversation at OZ Arts, Valk spoke about how her appearance as a performer in Foreman’s staging of Symphony of Rats in 1988 had left a subconscious desire to continue the dialogue with this “play with an open and indirect language” which motivated her to bring in back, this time in the role of the co-director. Valk spoke of wanting to rethink the play in a way that was truthful to Foreman’s language but unrecognizably different from his staging, which was Foreman’s hope as well when The Wooster Group approached him wanting to restage it. Unlike Foreman who had balanced the role distribution to two male and two female identifying actors, where the roles of the actresses were narrowed down to those of the entertainers of the president, this staging has a single female character (Michaela Murphy) who the directors described as an android. During the performance, her back is mostly turned to the audience, she moves props around the stage and serves as a mechanical sex object. When I asked if this was deliberate, LeCompte confirmed, also adding that the highest state of the woman present on stage is that of Alexandra, the digital human icon with a female voice, who rests in the higher realm of being, where the president in fact would like to be.

The precision of coordination between the performers, the sound and light cues, the video works, which show a variety of indicative imagery, from parts of the president’s body being scanned under an ex-ray machine to scenes from the antihero/supervillain movie Suicide Squad to which the actors on stage dub a perfectly synchronized soundscape, are a testament to the assiduous preparations and hard work put into staging Symphony of Rats. Periodical rehearsals for it lasted between December 2021 to its premiere in March 2024. LeCompte and Valk didn’t hesitate to reveal the function of the monitors that were present on stage and above the audience where the actors were receiving audio-visual material that they had rehearsed responses to, one of it being LeCompte’s sister’s hand gestures which she had filmed a few days ago to which the president’s character was responding to. Valk further clarified that the monitors allow the actors to free themselves from conscious embodiments of certain ways of acting, thus enabling them to reinvent something new yet fleeting during each performance.

The sense of humor, clarity, and modesty with which LeCompte, Valk and Tipton shared their experiences of working together, their openness to share mishaps and shortcomings, their capacity to maintain a confrontational and challenging conversation by putting each other on the spot but also giving credit and putting each other on the spotlight, demonstrate nothing less than an organic process of working together that is filled with passion and respect. Symphony of Rats was a treat, an inspiration for theater makers to free their minds, and audiences to question what they consider theater, but so was the artist conversation following the premiere, a rare opportunity to be in direct contact with the foremothers of the American avant-garde theater.